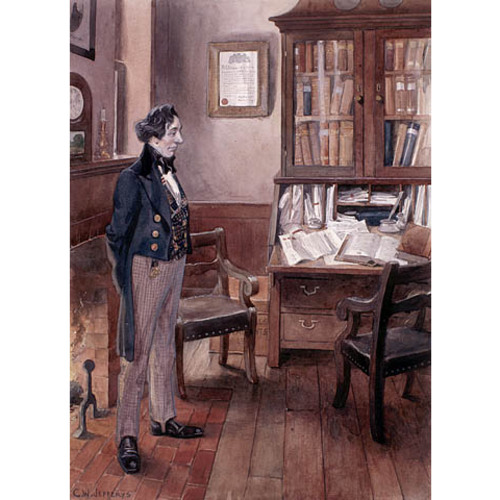

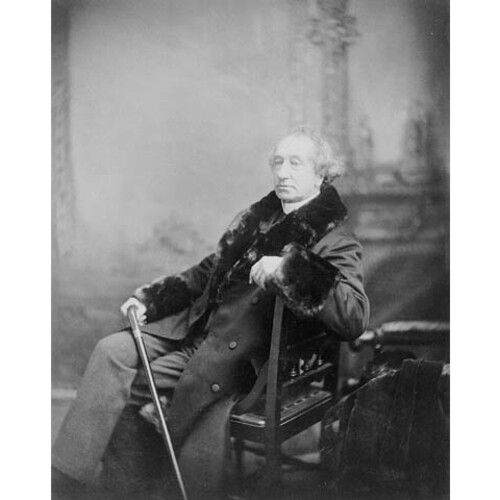

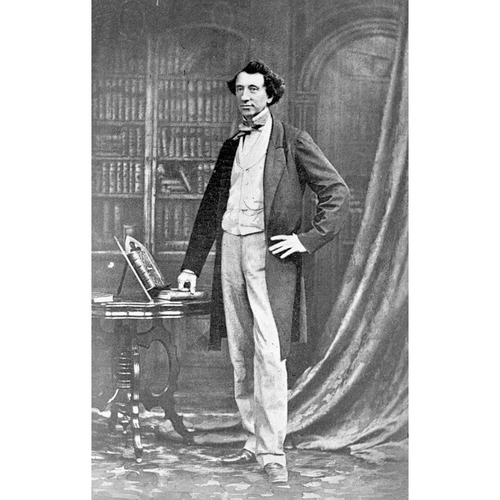

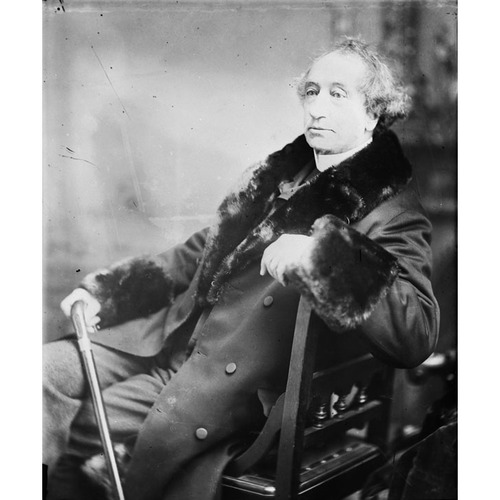

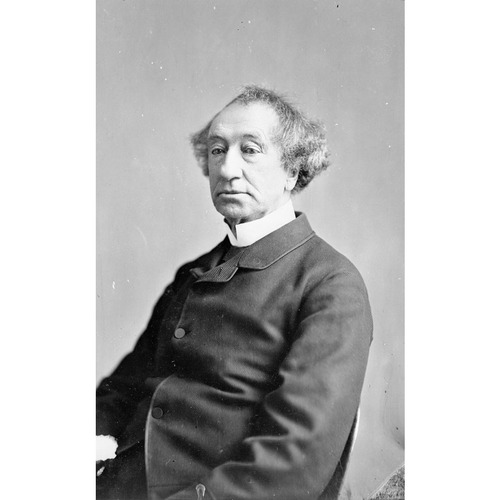

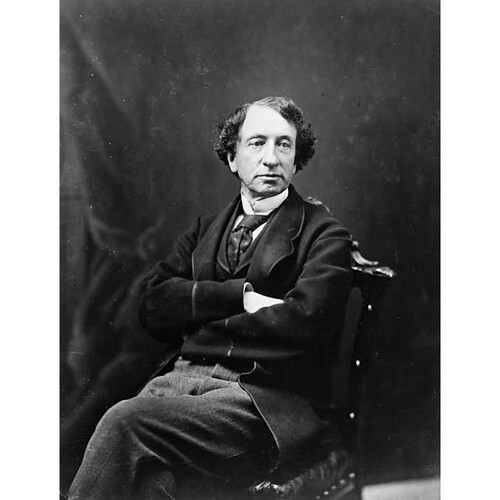

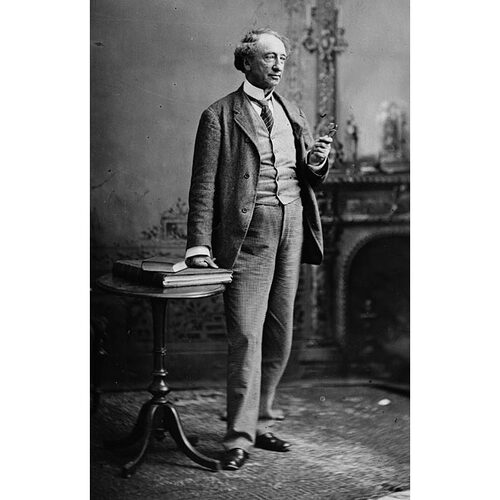

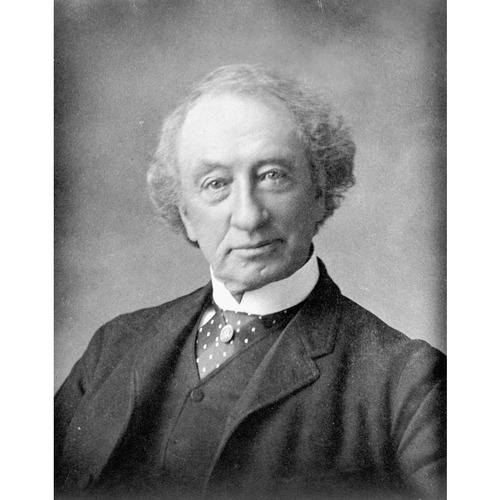

MACDONALD, Sir JOHN ALEXANDER, lawyer, businessman, and politician; b. 10 Jan. 1815 (the registered date) or 11 Jan. (the date he and his family celebrated) in Glasgow, Scotland, son of Hugh Macdonald and Helen Shaw; m. first 1 Sept. 1843 Isabella Clark (d. 1857) in Kingston, Upper Canada, and they had two sons; m. secondly 16 Feb. 1867 Susan Agnes Bernard* in London, England, and they had a daughter; d. 6 June 1891 in Ottawa.

Early life

Education

John Alexander Macdonald was brought to Kingston at the age of five by his parents, in-laws of Donald Macpherson*, a retired army officer living near Kingston. His father, who had been an unsuccessful merchant in Glasgow, operated a series of businesses in Upper Canada: merchant shops in Kingston and in Adolphustown Township, and for ten years the large stone mills at Glenora in Prince Edward County. Though never a man of wealth, Hugh Macdonald achieved sufficient local prominence to be appointed a magistrate for the Midland District in 1829. He and his wife saw to it that John received as good an education as was available to him at the time. He attended the Midland District Grammar School in 1827–28 and also a private co-educational school in Kingston, where he was given a “classical and general” education which included the study of Latin and Greek, arithmetic, geography, English reading and grammar, and rhetoric. His schooling provided appropriate training for his choice of profession, the law. In 1830, at age 15, he began to article in the office of a Kingston lawyer, George Mackenzie*. He quickly distinguished himself. Two years later he was entrusted with the management of a branch of Mackenzie’s office, in Napanee, and in 1833–35 he replaced his cousin Lowther Pennington Macpherson in the operation of the latter’s legal firm in Hallowell (Picton). In August 1835 he opened his own firm in Kingston, six months before being formally called to the bar on 6 Feb. 1836. From 1843 he usually practised with one or more partners, first with Alexander Campbell and then, from the 1850s, with Archibald John Macdonell and Robert Mortimer Wilkinson.

Success in the law

As a lawyer, Macdonald quickly attracted public attention, mainly by taking on a number of difficult and even sensational cases, including the defence of William Brass*, a member of a prominent local family who was convicted of rape in 1837, and a series of cases in 1838 involving Nils von Schoultz* and others charged with involvement in the rebellion of 1837–38 and in subsequent border raids. (In December 1837 Macdonald himself had served as a militia private.) Though he lost as many of these cases as he won, he acquired a reputation for ingenuity and quick-wittedness as a defence attorney. In fact, he did not long find it necessary to depend on a practice dedicated to the defence of hopeless cases. In 1839 he was appointed solicitor to the Commercial Bank of the Midland District and was made a director. From that point on his practice essentially concerned corporate law, especially after he gained as a client Kingston’s other major financial institution, the Trust and Loan Company of Upper Canada, founded in 1843. Though he acted at times for a wide range of businessmen and businesses, among them the company of Casimir Stanislaus Gzowski, the Trust and Loan Company for many years provided Macdonald with the bulk of his professional income.

Business interests

Macdonald was himself an active businessman, primarily involved in land development and speculation. Throughout the 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s he bought and developed urban property, first in Kingston and subsequently in Guelph and Toronto, and he bought and sold, often through agents, farm and wild land in many parts of the province, in parcels as large as 9,700 acres at a time. He also acted as an agent for British investors in Canadian real estate. Connections formed with British businessmen who were directors of the Trust and Loan Company led to his being appointed, in 1864, president of a British-backed firm in Quebec, the St Lawrence Warehouse, Dock and Wharfage Company. He acquired directorships in at least ten Canadian companies, in addition to the Commercial Bank and the Trust and Loan Company, and he sat on two British boards. As well, he invested in bank stock, road companies, and Great Lakes shipping. Macdonald’s business career was not, however, uniformly successful. He was caught at the time of the depression of 1857 with much unsaleable land on which he had to continue to make payments. In the 1860s he would suffer serious reverses because of the recklessness and sudden death of his legal partner, A. J. Macdonell, and the collapse of the Commercial Bank, which had advanced Macdonald loans. Nonetheless, he managed to avoid failure, continuing to draw income from his law partnership and from the sale and rental of real estate.

Family life

Macdonald had a good many personal as well as business problems to deal with. In 1843 he had married his cousin Isabella Clark, who, within two years of their marriage, became chronically ill, suffering from mysterious bouts of weakness and pain. A modern medical examination of her symptoms concludes that “she suffered from a somatization disorder, perhaps with a migrainous component, secondary opiate-dependence and pulmonary tuberculosis.” Isabella bore two children; in both cases the pregnancies and deliveries were extremely difficult. The first child, John Alexander, died at the age of 13 months. The second, Hugh John*, would survive. Isabella herself died in 1857.

First years in politics

Entry into public life

From an early age Macdonald had shown a keen interest in public affairs. He was ambitious and looked for opportunities wherever he could find them. At age 19, in 1834, he became secretary of both the Prince Edward District Board of Education and the Hallowell Young Men’s Society. In Kingston he was recording secretary of the Celtic Society in 1836, president of the Young Men’s Society of Kingston in 1837, vice-president of the St Andrew’s Society in 1839, and a prominent member of the Presbyterian community. In March 1843, now well known as a lawyer, businessman, and public-spirited citizen, he was easily elected to the Kingston Town Council as an alderman.

Election to the Province of Canada assembly

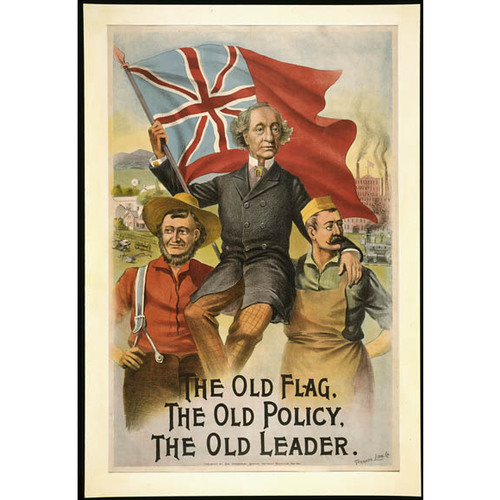

Macdonald’s three-year service at the local level was quickly overshadowed by his entry into provincial politics in the general election of October 1844. He ran in Kingston as a conservative, stressing his belief in the British connection, his commitment to the development of the Province of Canada, and his devotion to the interests of Kingston and its hinterland. Again he was elected by a wide margin; provincially, conservative winners outnumbered reformers by more than two to one.

Political views

It has been said that Macdonald’s political views were influenced by his legal mentor, George Mackenzie. While Macdonald was in his office, Mackenzie had advocated a moderate conservatism which stressed commercial expansion but also adhered to such traditional tory notions as state support for religious institutions and leadership by an elite. At any rate, in his early years in the Legislative Assembly Macdonald proved to be a genuine conservative, opposing responsible government, the secularization of the clergy reserves, the abolition of primogeniture, and extensions to the franchise, because such measures were un-British and could weaken the British connection or the authority of the governor and also the necessary propertied element within government and society. Yet he was never an entirely reactionary conservative. His approach to politics from the first was always essentially pragmatic. The fact was that circumstances made it impossible for Macdonald, or any other conservative politician, to cling to political positions that had become outmoded. The transfer of power from the governor and his appointed advisers to elected colonial politicians and the gradual acceptance of party politics created a system in which exclusivist views could not be maintained, at least in public. Macdonald preferred conservative options but did not wish, he stated in 1844, “to waste the time of the Legislature, and the money of the people, in fruitless discussions of abstract and theoretical questions of government.”

Assemblyman for Kingston, 1844–54

For six of the first ten years of his political career – between 1848 and 1854 – his party was not in power and his practicality was expressed mainly in efforts to promote the interests of his constituency. He regularly presented petitions and introduced legislation dealing with such matters as the incorporation of Kingston as a city; its debt; support for its charitable, religious, and educational bodies; and particularly the promotion of such Kingston-area businesses as road and railway companies, insurance companies, financial institutions, and gas, light, and water companies. (Macdonald had a personal financial interest in all of these businesses.) He was a conscientious and successful constituency man and would be re-elected from Kingston in seven consecutive elections for the assembly between 1844 and 1867 and in three for the federal house between 1867 and 1874.

Rise to political prominence

Entry into cabinet

Macdonald’s first experience as a cabinet member was in 1847–48, when he served for seven months as receiver general and for three as commissioner of crown lands in the administrations headed by William Henry Draper* and Henry Sherwood*. In these posts Macdonald proved himself an able and even a reformist administrator, but his chief political initiative was devising and advocating the University Endowment Bill for Upper Canada in 1847. It did not pass, but it reflected both his conservatism and his pragmatism. In an attempt to steer a middle course between the reform policy of a single state-supported, nonsectarian university and tory plans for a revived and strengthened Anglican King’s College in Toronto, he proposed to divide the university endowment among the existing denominational colleges but to give King’s College the largest share. In 1848 he resigned with the government to make way for the reform administration of Robert Baldwin* and Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*.

Formation of the Liberal-Conservative coalition, 1854

Macdonald did not hold office again until September 1854, when he became attorney general for Upper Canada in the newly formed coalition government of Sir Allan Napier MacNab* and Augustin-Norbert Morin*. His role in the formation of that coalition, from which some historians have dated the emergence of the modern Conservative party, is not entirely clear. The traditional version of the formation, which appears to have begun with John Charles Dent*’s account in The last forty years (1881), was that “his was the hand that shaped the course” of the negotiations. Donald Robert Beer’s well-founded modern view is that there is “no direct evidence” of Macdonald’s “special contribution to these events.” The exact extent of his involvement will probably never be known, but it is certain that the expanded party created in 1854 exactly fitted his own plan, mentioned in a letter to James McGill Strachan* in February of that year, to “enlarge the bounds of our party” and was in line with his already established “friendly relations with the French.” In 1861 Macdonald himself dated the existence of a solidly based Liberal-Conservative coalition from that occasion, “when I took them [the Conservative party] up in 1854.”

Attorney general and separate schools legislation, 1855

As attorney general (a position he would hold until 1867 except for periods in 1858 and 1862–64), Macdonald assumed a heavy administrative load because the office not only oversaw the judicial and penal systems of Upper Canada, but also handled a constant stream of references from the other government departments on points of law. He again proved a competent, if somewhat spasmodic, administrator and was shrewd in his choice of expert and efficient deputies: Robert Alexander Harrison* (1854–59) and Hewitt Bernard (1858–67). In the assembly he assumed an increasing share of the legislative load. His first major task was to steer through the act for the abolition of the clergy reserves, a measure that demonstrated his conservatism and his pragmatism by preserving a share of the revenues for clerical (mostly Anglican) incumbents but at the same time disposing of a long-standing, contentious issue. As he said in November 1854, “You must yield to the times.” In the same session, in early 1855, he assumed responsibility in the lower house for a controversial bill on Upper Canada’s separate schools, for which the Roman Catholic Church, led by Bishop Armand-François-Marie de Charbonnel, had lobbied the government. The bill was introduced first in the Legislative Council by Étienne-Paschal Taché* and in the assembly only in May, near the end of the session, when many Upper Canadian members had already left Quebec (the capital). Though provision for separate schools in Upper Canada had existed since 1841 [see Egerton Ryerson*], the act of 1855 really created the basis of the system that was to persist in Upper Canada and then in Ontario. It was defended by Macdonald on religious grounds – the right of Roman Catholics, according to the Toronto Globe’s report in June, “to educate their children according to their own principles.” The bill itself and the manner of its introduction had been severely criticized by Joseph Hartman* and others, and ultimately opposed by a majority of Upper Canadian members, but it had passed on the strength of French Canadian Catholic votes. Macdonald was accused, probably rightly, of parliamentary manipulation and he laid the government open to a charge of “French domination” of the administration. The issue also provided arguments for those in Upper Canada, led by George Brown* of the Globe, who since 1853 had advocated the introduction of a system of representation by population in the provincial parliament, which would have given Upper Canada a greater number of seats than Lower Canada.

Party co-leadership

In 1856 Macdonald became, for the first time, leader of the Upper Canadian section of the government, replacing MacNab. The manner in which he assumed control has been the subject of some controversy. MacNab had come under increasing criticism within the coalition because of his lingering reputation as an old “family compact” tory and his growing ineffectiveness due to ill health. No doubt he should have resigned but he refused, making it necessary to force him out of office so that a reconstruction of the cabinet could occur. Macdonald does not appear to have acted purely out of personal ambition; he too had become convinced that MacNab had to go. He took part in the ouster, first by sending MacNab an ultimatum, which he rejected, and then by joining the Reform members of the cabinet, Joseph Curran Morrison* and Robert Spence*, in resigning from it on 21 May (the other Upper Canadian Conservative, William Cayley*, soon followed) on the grounds that the government had been in a minority among the Upper Canadian members on a vote of confidence. MacNab had no choice but to place his portfolio at the disposal of Governor General Sir Edmund Walker Head*. The cabinet was reorganized on the 24th, with Taché as premier and Macdonald as co-premier. Macdonald now assumed the leadership role he was to hold for the rest of his life.

Liberal-Conservative leader

Leadership style

His approach to political power and responsibility was in practice highly personal. Before confederation he always shared the direction of the government and his party with a French Canadian leader, especially after November 1857 when the energetic George-Étienne Cartier* took over from Taché. Macdonald himself kept a firm hand on the affairs of the party in his own section of the Province of Canada. He was its chief strategist, fund-raiser, and, during elections, campaign organizer. He intervened directly at the riding level to ensure that suitable candidates were nominated, often having to sort out the rival claims of as many as six potential Liberal-Conservative mlas and, if necessary, “buying off” (usually with the promise of a government appointment) those who might create a party “split.” He advised candidates on policy and tactics and arranged election funding where necessary. He attempted to acquire the bloc support of a number of large groups, such as the Orange order and the adherents of the Methodist and Catholic churches, by appealing to the leaders of these organizations, including Ogle Robert Gowan*, Ryerson, and bishops Rémi Gaulin* and Edward John Horan*, for their influence with their followers. Despite his best efforts, however, Macdonald was not notably successful in winning elections in Upper Canada before confederation. In 1861, after his first extensive speaking tour and a campaign in which he advocated a British North American federation and raised the old “no looking to Washington” cry of loyalty, his candidates achieved only a small majority of Upper Canadian seats. In the other elections under his management, in 1857–58 and 1863, the Upper Canadian Conservatives were defeated.

Problems with alcohol

Macdonald was nevertheless an adroit politician and a popular campaigner. He successfully combined political shrewdness with a talent for conviviality and for good-humouredly persuading his colleagues to follow his lead. On the platform he projected a no-nonsense political image, coupled with a flair for ridiculing the foibles of his opponents. Clearly, by 1855 colleagues recognized Macdonald’s capacity for drink and soft sawder as important elements of his strength; others underestimated his skills because of them. But on occasion he was a hard drinker. The first time his drinking seems to have been a serious public problem was in the spring of 1862, at a time of government instability and during debate on a bill to expand the militia that Macdonald had introduced and defended. The Globe reported him as having “one of his old attacks.” Because Macdonald took so much personal responsibility for leadership, when he went on a binge, his party drifted. On 21 May 1862, after the defeat of the bill, the government resigned.

Dependence on French-English cooperation

The truth was that the Upper Canadian Conservatives had usually been sustained in power by their alliance with Cartier and the Bleu bloc, which held a majority in Lower Canada. This relationship had obvious political advantages and reflected both Macdonald’s belief in French-English cooperation and his long-standing commitment to the union of Upper and Lower Canada as an economic necessity. The relationship also meant that his brand of Conservatism had become more and more unpopular in his own section of the province and increasingly open to charges of “French domination” of the ministry. Whether from conviction or necessity, Macdonald had been forced to defend, against a hostile Protestant majority in the population of Upper Canada, the system of Catholic separate schools. He personally opposed representation by population as a basis for the distribution of seats in the assembly, even though most Upper Canadians and eventually many of his Upper Canadian Conservative followers, among them John Hillyard Cameron*, came out in support of the principle. After 1851 the population of the western section of the province exceeded the east’s so that adopting the principle would have reduced the effectiveness of the French Canadians as a political group. Macdonald also, like Cartier, showed limited enthusiasm for another popular Upper Canadian movement, the annexation of the vast territory west of Canada. Though the Taché–Macdonald government in 1857 made a vague claim to the lands then under the jurisdiction of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Macdonald was not much concerned. In 1865 he was to state in a letter to Edward William Watkin, the former Grand Trunk president who had examined the question of confederation for the Colonial Office, that he was “quite willing personally to leave that whole country a wilderness for the next fifty years.” Thus in the period 1854–64 he was in a kind of political trap of his own making. To stay in power, he needed French Canadian support, but that necessity in turn involved support for policies that were a political liability in his own section of the province.

Uses of government patronage

Macdonald tried to compensate for the political weakness of Conservatism in Upper Canada in a number of ways. He insisted that the party officially remain a coalition of moderate Reformers and Conservatives, and he always kept a succession of Hincksite Reform members, such as Morrison, Spence, and John Ross*, or Reform defectors such as Michael Hamilton Foley* or Thomas D’Arcy McGee* in the cabinet to try to broaden his party’s image and appeal. He also tried to compensate for political shortcomings by developing a centralized system of government patronage. Macdonald was, of course, far from the first politician to dispense patronage but, unlike his Conservative predecessors, he maintained a strong personal hold over office-giving while in power, and he used offices, or the promise of office, in a deliberate attempt to strengthen the party at the local level, on the principle that reward should result only from actual service. By making sure that recommendations on patronage were “attached to the legal department,” as Macdonald stressed in January 1855, and by working hard on behalf of people to whom he had made commitments, he was able to raise the level of loyalty to the party, and to himself, throughout the province.

Governance of Upper Canada

Legislative achievements, 1854–62

Though never associated with legislation that produced dramatic or sweeping reforms, during the period when he was most influential as attorney general, party leader, or co-premier (1854–62), he oversaw, particularly in the late 1850s, the introduction of measures and administrative changes which contributed a good deal to the efficient running of a rapidly expanding and changing province. In the 1850s in Canada the state had just begun to assume responsibility for social welfare; the only existing provincial institutions in Upper Canada were the penitentiary at Kingston and the lunatic asylum in Toronto [see Joseph Workman]. Between 1856 and 1861 branches of the asylum were opened in Toronto, Amherstburg, and Orillia. An institution for the criminally insane was established in Kingston in 1858. The first reformatory for juvenile offenders began in temporary quarters in Penetanguishene the following year. By the act of 1857 that provided for the asylum for the criminally insane and the reformatory, a permanent board of inspectors was created to oversee and set standards for all state welfare and correctional institutions, including 52 local jails. Under Macdonald’s leadership the basis of a public social-welfare system was laid down and gradually extended. In 1866 the Municipal Institutions Act (rescinded after confederation) required the establishment of a house of industry or a refuge for the poor in each well-populated county within two years.

Choice of provincial capital

During the same years a great deal of expansion and reorganization of the government’s bureaucracy was undertaken. The question of a permanent seat of government, which had exacerbated urban rivalries for years, was settled by the ingenious device, on the part of Macdonald and others, of referring the issue to the queen in 1857 [see Sir Edmund Walker Head]. Announcement of her choice of Ottawa occasioned the temporary defeat of the Macdonald–Cartier government in July 1858, but when the Reformers under George Brown were unable to attract a parliamentary majority, it returned to office within 48 hours by means of the controversial “double shuffle” manœuvre [see Sir George-Étienne Cartier; William Henry Draper]. In 1859 a parliamentary decision in favour of Ottawa was finally reached by a majority of five votes.

Deputy ministers and new departments

The Civil Service Act of 1857 established the rule that each major government agency would have a permanent, non-political head called a deputy minister. A first attempt to bring fiscal responsibility into government had been undertaken in the Audit Act of 1855 and the appointment of Macdonald’s friend and former Conservative colleague John Langton as auditor of public accounts. Further financial change occurred in 1859 when the office of inspector general was elevated to a full-fledged Department of Finance, completing a long process by which the office of receiver general, who was originally the province’s most important financial officer, was downgraded to a minor post. Two new departments were created. The Bureau of Agriculture and Statistics, established in 1857, became a full department in 1862 [see Joseph-Charles Taché]. The previous year Macdonald had imposed a political head, the minister of militia affairs, upon the bureaucratic post of adjutant general of militia. In December 1861 Macdonald himself assumed the responsibility of being the first minister, a post which he held until May 1862, during the sensitive opening year of the American Civil War, and again in 1865–67, at the time of the Fenian raids. The expansion included the creation in 1857, within the Crown Lands Department, of a fisheries branch, charged with preserving and protecting freshwater fish-stocks, and, more significant, the assumption by the province in 1860 of complete responsibility for Indian affairs, previously under imperial control [see Richard Theodore Pennefather*].

Attempts were also made to develop areas of a province that was rapidly running out of accessible agricultural land. In 1858 two temporary judicial districts (Algoma and Nipissing) were established, tightening the government’s control in these thinly populated northern areas. A network of colonization roads was planned under the direction of Crown Lands to encourage settlement in the southern section of the Canadian Shield beyond the existing areas of cultivation. These roads when built were never successful in their agricultural purpose (though they were helpful to the lumber industry), but the construction of several during Macdonald’s period in office reflected his often-expressed view that there was a “fertile back country” which only needed an improved transportation system to permit it to develop.

Macdonald–Cartier government initiatives

In the late 1850s, and especially in 1857, when more bills were passed than in any other year in the entire union period, the Macdonald–Cartier government undertook many legislative initiatives, including the Independence of Parliament Act (1857), amendments to the Municipal Corporations Act (1857 and 1858), an act for the registration of voters (1858), and amendments (1858) affecting the operation of the surrogate courts, the usury law, the composition of juries, and imprisonment for debt (it was abolished in most cases). As attorney general, Macdonald was responsible for a number of significant reforms of the judicial system itself, among them the Common Law Procedure Act (1856), the County Attorneys Act (1857), and an act which permitted appeal in criminal cases (1857). In addition, this business-oriented government adopted a wide range of measures to stimulate economic growth. These included not only continued support of the Grand Trunk Railway but also, in the budget brought in by Inspector General William Cayley in 1857 and seen through the legislature by Alexander Tilloch Galt the following year, the first tariff system of “incidental protection” for Canadian industry. This system, foreshadowing the National Policy of the 1870s, was responsible for “numerous manufactories of every description which have sprung up in both sections of the province,” according to Macdonald in 1861. In 1859 Postmaster General Sidney Smith*, one of Macdonald’s closest political friends, concluded arrangements with the United States, Great Britain, France, Belgium, and Prussia for mail service to Canada and the United States. Macdonald and his colleagues also encouraged and supported a large number of acts incorporating new businesses and expanding the scope of existing ones, including road and rail companies, insurance companies, banks, mining, oil, and lumber companies, and many others, in some of which Macdonald and his parliamentary associates had a personal interest.

Relations with First Nations

Another measure that Macdonald introduced as attorney general was a bill that was to have a long-lasting, negative impact on First Nations. Its subject was enfranchisement, which in First Nations policy meant Indigenous people giving up their Indian status and becoming citizens. In 1850–51 the Canadian legislature had established a form of Indian status as part of new legislation to protect reserve lands from encroachment by non-Indigenous people. At the same time the colony had developed policies, including residential schooling, to induce members of First Nations to surrender this status when they felt ready to do so. The government’s thinking was that the transformative influence of Euro-Canadian education and the adoption of a non-nomadic life based on farming would acculturate First Nations. In 1854 Governor Lord Elgin [Bruce*] had argued, “If the civilizing process to which the Indians have been subject for so many years had been accompanied by success, they have surely by this time arrived at a sufficiently enlightened condition to be emancipated from the state of pupilage in which they have been maintained.”

The Macdonald–Cartier ministry took the next step in 1857, when Macdonald introduced, and the legislature passed, the Gradual Civilization Bill. The measure held that “it is desirable to encourage the progress of Civilization among the Indian Tribes in this Province, and the gradual removal of all legal distinctions between them and Her Majesty’s other Canadian Subjects, and to facilitate the acquisition of property and of the rights accompanying it, by such Individual Members of the said Tribes as shall be found to desire such encouragement and to have deserved it.” The legislation envisaged the enfranchisement of Indigenous males of good moral character who were able to speak, write, and read English or French, who were debt-free, and who were considered to have been adequately educated. Those who could not read or write either language, or those deemed to be insufficiently educated, could undergo an examination, and, if the results were judged satisfactory, could begin a three-year probation, at the successful completion of which they would become enfranchised. Enfranchised men would lose Indian status, as would their wives and children and all their descendants. In return, they were to obtain up to 50 acres in freehold tenure from their former reserves, an acquisition that put them on the road to meeting the property qualifications for voting, as well as a share of the annuities paid to their band. These provisions, which after confederation would be embodied in the consolidated Indian Act of 1876 and at that time restricted to the country east of Manitoba, would remain law until 1985 (except for the 13 years following the passage of the Electoral Franchise Bill in 1885). Only a few Indigenous people, such as Solomon White* in Ontario, availed themselves of the legislation. It nevertheless had an intimidating effect on many.

Path to confederation

Opposition to union

Macdonald went into opposition in 1862 when the Militia Bill was defeated in the assembly. He returned to office two years later, in very different political circumstances. The election of 1863 had returned almost twice as many Reformers as Conservatives in Upper Canada, but the situation overall, owing to the continued strength of Cartier’s Bleus and the English-speaking Conservatives of Lower Canada, was a virtual stalemate. An administration led by the Reformers John Sandfield Macdonald* and Louis-Victor Sicotte*, and then another formed in March 1864 by E.-P. Taché and Macdonald, each failed to sustain majority support. A constitutional committee of the legislature chaired by George Brown, of which Macdonald was a member, reported on 14 June in favour of a federal system of government for the two sections of Canada or for all of the British North American provinces. This proposal received wide support in the Province of Canada because it offered a way out of the highly polarized political deadlock and would provide Upper and Lower Canada with separate provincial governments, thus allowing for greater regional freedom of action and a lessening of sectional and French-English tensions. Macdonald, however, with two others from Brown’s 20-member committee, refused to endorse its report, which was supported by almost all of the leading Canadian politicians of the day. Though he had been part of an administration which, as early as 1858, favoured a federal union, he had always been cool to the idea because, he stated in a public address in 1861, he feared a federation would have “the defects in the Constitution of the United States” – a weak central government. Macdonald had always preferred a highly centralized, preferably unitary, form of government that would not be torn by jurisdictional disputes, which, he believed, had been “so painfully made manifest” during the Civil War.

Formation of the Great Coalition, 1864

Despite these strong misgivings about federation, when Brown suggested combined action to bring about constitutional change, Macdonald reversed his stand. His shift came within two days, on 16 June 1864. The result was the formation on the 30th of the “Great Coalition,” by which the majority of the Upper Canadian Reformers joined with Macdonald’s Conservatives and Cartier’s Bleus for the purpose of creating a federal union of British North America. The reasons for Macdonald’s abrupt change of mind were both visionary and entirely practical. Federation would “prevent anarchy,” “settle the great Constitutional question of Parliamentary Reform in Canada,” and “restore the credit of the Province abroad.” In other words, the united provinces would form a larger, stronger, more harmonious community and even a potential rival to the United States. More immediately, the coalition allowed him to escape from serious political difficulties in his own section of Canada, where the Reform party appeared to be gaining unbeatable strength. “I then had the option,” he wrote privately in 1866, “either of forming a Coalition Government or of handing over the administration of affairs to the Grit party for the next ten years.”

American Civil War

From 1864 to 1867 Macdonald was preoccupied with two overriding concerns: the Civil War – its aftermath and its implications for Canada – and the not unrelated matter of the confederation of British North America. In October 1864 a raid on St Albans, Vt, by Confederate soldiers operating from Canada and their later release on a technicality by Montreal magistrate Charles-Joseph Coursol* caused a strong anti-Canadian reaction in the United States. In December its government demanded that all persons entering the United States from British North America be required to hold a passport, and Congress began proceedings for the abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty, in force since 1854. The Canadian government responded by calling out 2,000 militia volunteers to attempt to prevent further incidents along the border. As attorney general, Macdonald authorized the creation of a small “detective and preventive force” to gather information, using Canadian agents and American informants in several American cities. In charge of this first Canadian secret-service unit (which became the Dominion Police after confederation) Macdonald, in December, placed a “shrewd, cool, and determined man,” a Scottish immigrant and former mla named Gilbert McMicken. He reported directly and secretly to Macdonald, who in August 1865 once again added the responsibilities of minister of militia affairs to those of attorney general.

Fenian raids and Charlottetown conference

In 1865 Macdonald and McMicken were also forced to become concerned about the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish-American paramilitary organization dedicated to the liberation of Ireland. There were fears of Fenianism spreading into Canada and there were rumours and a few incidents of armed organization on the part of the Hibernian Benevolent Society of Canada [see Michael Murphy*], but the menace turned out to be external. In 1866 raids were launched on Campobello Island in New Brunswick and, with more success, across the Niagara River at Fort Erie [see John O’Neill*]. Fenianism thereafter faded as a threat to British North American security, but events of 1864–66 undoubtedly contributed to an “atmosphere of crisis” which had an important effect on the rapid achievement of a federal union and on the form it took. The coalition government established in 1864 was under the titular leadership of Taché, but Macdonald quickly became the mainspring of the confederation negotiations that followed. Brown had wanted the coalition first to pursue a federal union of the two Canadas alone. Macdonald insisted, and got his way, that the priority should be a union of all the provinces. An opportunity to further this aim presented itself, since the Maritime provinces had already begun preparations for a regional conference to discuss the possibility of a legislative union of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island [see Arthur Hamilton Gordon*; Sir Charles Tupper*]. Viscount Monck, governor general of British North America, arranged with the lieutenant governors of those provinces to allow a Canadian delegation to attend the conference, planned for Charlottetown, to present informally a proposal for federation. During the summer of 1864 the Canadian cabinet prepared its proposals. When the delegation arrived at the conference in September, it was invited to present its case at once, before any discussion of Maritime union. Macdonald spoke first, beginning a process that was to culminate with the passage of the British North America Act three years later. It led to the Quebec conference in October 1864 between representatives of Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland, and eventually to the final meetings of the delegates of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick with the British government in London between December 1866 and February 1867.

Father of confederation

British North America Act, 1867

The extent to which Macdonald was personally responsible for the form and substance of the confederation agreement has been the subject of debate, but there is no doubt that he was the dominant figure throughout the events of 1864–67. At the Quebec conference he was the principal spokesman for the Canadian scheme, which had been worked out in some detail. He chaired the meetings in London in 1866–67 (in February 1867 he married there). The British North America Bill, for the federal union of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, was signed into law on 29 March 1867, to be proclaimed on 1 July. Macdonald’s role was amply recognized in Great Britain. He was the only colonial leader to be awarded an honorary degree (from Oxford in 1865) or to be given a knighthood (conferred 29 June 1867, announced 1 July), and he was, of course, selected as the first prime minister of the Dominion of Canada. (He had been asked by Monck in May to form the first administration.)

Certainly, much of the constitutional structure of the dominion was his creation. He could not say so publicly, but in private he claimed almost complete responsibility for the confederation scheme on the grounds that he alone had possessed the necessary background in constitutional theory and law. In the “preparation of our Constitution,” he had told his close friend county court judge James Robert Gowan* in November 1864, “I must do it alone as there is not one person connected with the Government who has the slightest idea of the nature of the work.” His colleague Thomas D’Arcy McGee said in public in 1866 that Macdonald was the author of 50 of the 72 resolutions agreed upon at Quebec.

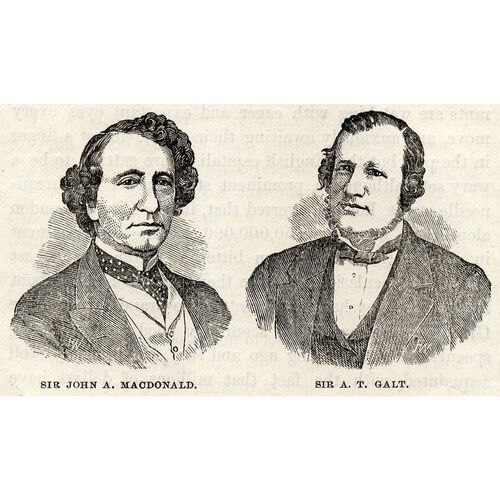

Even at the time some played down Macdonald’s role. George Brown challenged McGee’s statement in the Globe and attributed the confederation plan to the collective efforts of the Canadian cabinet. Certainly there were aspects which Macdonald did not initiate and some of which he did not particularly approve. The financial arrangements, as he admitted, were the work of A. T. Galt. Representation by population, the principle that governed membership in the lower house, had long been advocated by Brown and was made a fundamental part of confederation at his insistence. The provisions for the official use of the French language in parliament, in the federal courts, and in the courts and legislature of Quebec, as well as the continuance of the code civil in that province, were clearly Cartier’s contribution. The arrangements for the preservation of existing separate schools and for their establishment in new provinces were largely inspired by Galt. Before confederation Macdonald had never shared Brown’s great enthusiasm for extending Canadian jurisdiction into the northwest, or for an intercolonial railway, which was provided for in an unusual constitutional clause insisted upon in London by the Maritime delegates, who included Jonathan McCully*, William Alexander Henry*, and Samuel Leonard Tilley. To what extent, then, can the BNA Act be said to have been “the Macdonaldian Constitution”?

Views on central government

The terms of the act were not precisely what Macdonald would have wanted had he been allowed a free hand, but he believed that his main objectives had been achieved. His overriding goal had always been a system that, though federal in order to secure the assent of Quebec and the Maritimes, would be as centralized as possible, with a central government directed by a powerful executive. In the act the division of powers between the central and provincial governments reflected his aims. The federal powers were more numerous and contained the blanket phrase “Peace, Order and good Government.” In that phrase was the most sweeping grant of power known to the drafters at the Colonial Office, who supported Macdonald’s centralist position. Macdonald intended to have ample room for anything he wanted to do. The federal powers were also concerned with those areas of jurisdiction where Macdonald believed real power lay: national defence, finance, trade and commerce, taxation, currency, and banking. As well, the federal government was given the power (exercised by the imperial government before 1848) to disallow provincial legislation. (In June 1868 a justice department memorandum approved by cabinet for transmission to the provinces was to emphasize a new and exacting use of disallowance, so that even the strongest of provincial rights was to be subject to central surveillance.) The federal cabinet appointed its own provincial watch-dogs, the lieutenant governors, as well as the members of the Senate, the body designed by Macdonald to represent the well-to-do, propertied element of Canadian society, though the House of Commons would continue to be elected on a property franchise. Macdonald believed he had avoided the chief weaknesses of the American federation: universal suffrage and a weak executive. Canada would be run from the centre by people who had a genuine stake in the community. Macdonald’s omission from the BNA Act of a formula for amending the structures and powers of the central government was probably not, as is often suggested, an oversight. Having seen to it that the local legislatures could amend their own constitutional arrangements within the tight constraints of section 92, Macdonald would not have neglected something analogous in section 91, on the powers of parliament, had he thought he needed it.

Macdonald’s private agenda for the future of the new federation went much further than the BNA Act revealed. It was not just that a provincial government was to be “a subordinate legislature.” The provincial governments, he maintained, had been made fatally weak and were ultimately to cease to exist. He envisaged a Canada with one government and, as nearly as possible, one homogeneous population sharing common institutions and characteristics. In December 1864 he told Matthew Crooks Cameron* that “if the Confederation goes on[,] you, if spared the ordinary age of man, will see both Local Parliaments & Governments absorbed in the General Power. This is as plain to me as if I saw it accomplished but of course it does not do to adopt that point of view in discussing the subject in Lower Canada.” He was undoubtedly wise not to make such sentiments public, for among French Canadians, by whom the provincial governments were already being seen as the centre of what would become known as “provincial rights,” there were even in 1864 suspicions of his intentions. Ottawa’s Le Canada, edited by Elzéar Gérin*, argued in 1866, “The more the local legislature is simplified, the more its importance will be diminished and the greater the risk of its being absorbed by the federal legislature.” Macdonald thought he had set in motion an evolutionary constitutional process which in time would further alter the relative importance of the two levels of government. His colleague Hewitt Bernard, secretary of all the confederation conferences, had acquired an inner core of experience about how Macdonald’s constitutional ideas could be translated into practice. Asked by Governor General Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*] in 1874 to comment on the BNA Act in the light of seven years of operation, Bernard directed his criticisms mainly at making still more explicit and restrictive the provincial powers covered in section 92.

Creation of the federal government

Establishment of federal institutions

In many practical ways the administrative structure of the new dominion government was that of the Province of Canada shifted into a new gear. The capital remained at Ottawa, of course, and many of the old province’s deputy ministers and chief officers occupied senior positions in the federal civil service, among them Bernard, Joseph-Charles Taché, William Henry Griffin, Toussaint Trudeau, Edmund Allen Meredith, and John Langton. Macdonald was more ambitious than his colleagues to make not only constitutional room for central power but physical space as well. He wanted more land in central Ottawa than his colleagues would let him take. Macdonald wished, for instance, to take over Nepean Point for the governor general’s residence, but his colleagues would have none of it. He told Joseph Pope* years later that Rideau Hall had cost them more to patch up than a new residence would have cost at Nepean Point. Macdonald wanted to take the whole block between Wellington and Sparks streets east of Metcalfe for future departmental offices. His colleagues baulked at that too.

Minister of justice, 1867–73

The Department of Justice was the portfolio Macdonald himself chose in 1867 and the one he retained until the resignation of his government in November 1873. He supervised the splitting of functions in 1867, consigning those of his former office, the attorney generalship of Upper Canada, to the provincial government in Toronto. The senior staff in his old office remained with the new department; no break in Macdonald’s old departmental letter-books occurred.

His duties also tended to be a continuation of those he had carried as attorney general. The pardoning power, which belonged to the governor general, compelled Macdonald to review capital cases, and the penitentiary system was a federal responsibility. Federal involvement in both had been insisted upon by the Colonial Office; it is by no means certain that Macdonald wanted them. The penitentiary system he left to Hewitt Bernard, but in his policies he continued his tendency to be firm rather than charitable. The primary object of penitentiaries, he told John Creighton*, the warden in Kingston, in 1871, was “punishment, the incidental one, reformation.” It was possible to make prisons too comfortable, prisoners too happy. (Read David Copperfield, he said, particularly where Uriah Heep, in a model prison, is so much better off than poor people living outside it.) The power of release ought to be used sparingly. Certainty of punishment was of more consequence than severity of sentence. Macdonald attributed the high rate of crime in the United States to the ease with which pardons could be obtained through political pressure on state governors.

Assassination of D’Arcy McGee

When Thomas D’Arcy McGee was shot on 7 April 1868, the full power of the dominion government was placed at the disposal of the attorney general of Ontario, in whose hands lay the responsibility for prosecution. The dominion shared the expenses of prosecuting Patrick James Whelan*, and Bernard, as deputy minister of justice, took a prominent part in finding evidence in Ottawa. Although John Sandfield Macdonald was premier of Ontario as well as attorney general, Sir John virtually took over the case. He was implacable. Pressures arose for a stay of execution; even the prosecuting counsel, James O’Reilly*, seemed uncomfortable; John Hillyard Cameron, the defence counsel, thought there should have been a new trial or at the least an appeal to the Privy Council. Yet Macdonald was ordinarily of milder mien, especially in cases where the evidence was ambiguous. The death sentence of Baptiste Renard, convicted in 1864 of rape, had been commuted, as usual, to life imprisonment. Three years later, after Bishop Edward John Horan of Kingston brought new evidence to Macdonald’s attention, Renard was discharged.

Quelling dissent and expanding the union

The early sessions of the Canadian parliament showed Macdonald’s strong centralist views about the assimilation of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the Hudson’s Bay Company territory. The new North-West Territories, to be carved out of Rupert’s Land, were to become, Macdonald admitted, Canadian crown colonies, administered as such. He had things to learn; but the first year or so of confederation showed how firmly a central Canadian he was, sanguine about issues and difficulties that he was unfamiliar with. In the face of continuing anti-confederate sentiment in Nova Scotia, customs minister S. L. Tilley had to warn him in July 1868 from Windsor, N.S., “There is no use in crying peace when there is no peace. We require wise and prudent action at this moment.” Macdonald was a realist, but realism with him took the form of perceptions forced upon a sanguine temperament. This odd combination gave him the incentive, dodger that he was, to adapt, shift, make expedients. He would not bow down to difficulties: he would try to work his way out of them. In the case of Nova Scotia, the recklessness of its premier, Charles Tupper, in pressing the province to enter confederation and his own central Canadian perspective had got him into trouble; when he moved it was late, but he acted with skill, courage, and resourcefulness. He travelled to Halifax in August 1868 in order to meet Joseph Howe* to work out measures to ease the conflict between Nova Scotia and the dominion.

The application of an “imperial screw” to Nova Scotia [see Sir William Fenwick Williams*] was not something he would willingly repeat. By 1869 he knew that as a mode for political unions it was counter-productive. At the end of that year Governor Stephen John Hill of Newfoundland suggested the colony might be added to Canada by imperial fiat. Macdonald would have none of it. Although terms of union had been negotiated with Canada by a delegation led by the island’s premier, Frederic Bowker Terrington Carter, in the fall general election Newfoundlanders had definitely pronounced themselves against confederation. That, as far as Macdonald was concerned, was that. He would not impose Canadian rule on another colony without local opinion being tested and found willing. This attitude explains his readiness to negotiate at the first sign of trouble at Red River (Man.) in 1869 [see Louis Riel*]. He would insist, for the same reason, on an election in British Columbia before confederation was cemented in place there in 1871. He would be endlessly patient with the demands, and elections, of Prince Edward Islanders. “I see that you have quite a political ferment about your Railway,” he wrote in October 1871 to his doctor in Charlottetown, William Hamilton Hobkirk. “I hope that the result of the increase of your pecuniary burdens will be your making a junction with the Dominion; but such a consummation ... can be hastened by no action on our part, it must arise altogether from your own people.”

Red River uprising, 1869–70

Rupert’s Land

The acquisition of Rupert’s Land was a major item on his 1869 agenda. This had been negotiated in London on Canada’s behalf largely by Cartier. He and William McDougall*, the minister of public works, arrived in London in October 1868; the latter was taken seriously ill almost at once. Cartier’s negotiations crossed two ministries, Disraeli’s on the way out and Gladstone’s on the way in. Although McDougall was convinced that Gladstone’s government would be more favourable to the Canadian cause, Cartier believed the opposite and he was right. Cartier left for Canada only on 1 April 1869, after six months of continuous negotiations. Under the dominion’s temporary government act, assented to in June, a lieutenant governor and council were to administer the territories, which were to be transferred formally to Canada on 1 December.

After McDougall accepted the office of lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories (what Macdonald privately called his “dreary sovereignty”), Macdonald followed up a long conference with him by letters full of good sense. “The point which you must never forget,” he advised sternly on 20 November, “is that you are now, approaching a Foreign country, under the Government of the Hudson Bay Company.... You cannot force your way in.” Macdonald encouraged him to retain Riel (a “clever fellow”) for his “future police,” and thus to give “a most convincing proof that you are not going to leave the half breeds out of the Law.”

Dissatisfaction of the Métis

For the troubles that had already arisen in the Red River settlement over a federal survey and the transfer of the northwest, Macdonald, so far as he knew of them, put some blame on local priests. He also put some, privately, on Cartier for having “rather snubbed” Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché of St Boniface that summer when he came through Ottawa on his way to Rome. Secretary of State Hector-Louis Langevin* was thought to have patched things up, but Macdonald believed by late November that Taché’s irritation had got back to Red River. The main burden of blame Macdonald put upon officials of the HBC. The dissatisfaction of the Métis was well known to its local council. The transfer had been planned and known of for months. HBC officer John H. McTavish had been in Ottawa in April, had seen Macdonald and others, and had been told of the transfer of the northwest to Canada with the same rights for its inhabitants as had existed before. Yet company officials gave no explanation to the people of Red River about what was to happen. “All that those poor people know,” Macdonald said to Cartier on 27 November, “is that Canada has bought the country ... & that they are handed over like a flock of sheep to us; and they are told that they lose their lands .... Under these circumstances it is not to be wondered at that they should be dissatisfied, and should show their discontent.”

Louis Riel’s provisional government

Macdonald’s advice to McDougall that same day, in the light of what was then known, was good law and common sense. He told McDougall in a letter not to cross the 49th parallel and not to be sworn in as lieutenant governor. The policy should be to throw full responsibility for the unrest on the HBC and the imperial government. A proclamation from McDougall calling for the loyalty of the people in Red River would be well if it were certain to be obeyed. But if it were disobeyed, Macdonald reasoned, McDougall’s weakness would be “painfully exhibited” to the people and to the Americans. If he were not admitted to the country, a proclamation would create anarchy; it would then be open to the inhabitants of Red River “to form a government ex necessitate for the protection of life and property, and such a government has certain sovereign rights by jus gentium.” The Americans might even be tempted to recognize it. This advice reached McDougall too late to save him from his own folly of 1 December, when he precipitately proclaimed the northwest to be part of Canada. A week later Riel established a provisional government. At about the same time, Macdonald sent emissaries, Charles-René-Léonidas d’Irumberry* de Salaberry and Abbé Jean-Baptiste Thibault*, when he thought reassurances were needed, and Donald Alexander Smith* as a commissioner to negotiate the moment he saw that real mediation was going to be necessary. What he did not want was the British government sending out an imperial commissioner. He believed, as did the whole Canadian cabinet, “that to send out an overwashed Englishman, utterly ignorant of the Country and full of crotchets as all Englishmen are, would be a mistake.”

When Taché came back through Ottawa in February 1870, Cartier ate as much humble pie as seemed requisite. But so sensitive was the northwest issue as a result of Thomas Scott*’s execution in March that two of the delegates sent east by Riel in March, Alfred Henry Scott* and Abbé Noël-Joseph Ritchot*, were arrested for complicity in the murder. Macdonald hired John Hillyard Cameron to help get them off and made the $500 payment privately so that it would not appear in public accounts.

Creation of new provinces

On 2 May a bill to create the new province of Manitoba was introduced in the House of Commons. Four days later, as the measure was being debated, Macdonald was struck down by the passage of a gallstone. He was so weak he could not be moved home, and his corner office in the east block became his sick-room. In early July Macdonald, his wife, his little daughter, his mother-in-law, Hewitt Bernard, Dr James Alexander Grant, a nurse, and a secretary went off to Charlottetown by government steamer from Quebec. The party arrived on 8 July and took up residence in a large rambling house in the suburbs. Macdonald was still so weak in the legs that he could not walk. It has been alleged that there, besides following the Franco-German War, Macdonald hatched the scheme to buy Prince Edward Island into confederation by getting its government to build a railway. Suspicions do not make evidence. What is certain is that Macdonald was not going to take the Island into confederation without a convincing display of local support. He was back in Ottawa on 22 September, impressing everyone with how well he looked.

He soon took hold of bringing British Columbia into confederation. Negotiations had been conducted by Cartier in June 1870. On 29 September Macdonald told the colony’s governor, Anthony Musgrave*, that though the terms Cartier had negotiated, including the construction of a transcontinental railway, could be justified on their merits, “considerable opposition” could be expected in parliament because they would likely be seen as too burdensome to Canada and too liberal to British Columbia. He therefore told Musgrave to try to follow the course taken when the Newfoundland resolutions were going through parliament in 1869: have members of the colonial government come to Ottawa to discuss awkward points with the mps, especially the Conservative caucus. In April–May 1871 Joseph William Trutch* came east for that purpose and helped Cartier secure parliament’s approval of the British Columbia terms of union.

Washington conference, 1871

Appointment as a British commissioner

Macdonald was again absent from the House of Commons. He had had to assume the thankless role of being a Canadian and an Englishman at the same time: as one of the British commissioners in the negotiations at Washington to settle outstanding Anglo-American differences, many of which affected Canada. One suggestion for a representative from Canada had been Sir John Rose*, formerly Canada’s finance minister, who had already conducted discussions on the same topic with American secretary of state Hamilton Fish. But Rose’s interests were now London and New York, and however much Macdonald trusted him – and that trust went a long way – his appointment was unacceptable politically. There seemed to be no one else for this ungrateful task but himself. He left for Washington on 27 February for what he would later describe as the “most difficult and disagreeable work that I have ever undertaken since I entered Public Life.”

Negotiations in Washington

Macdonald had seen little of the United States for 20 years, and the commission was his first extended contact with American statesmen. He was surprised to find them agreeable socially; that did not make them less dangerous diplomatically. Of the pressing issues, the Alabama claims was the most serious, but the commission, for the moment, could only agree to disagree on it. The full weight of negotiations then fell upon the Canadian inshore fisheries. Free access to those fisheries had ended when the Reciprocity Treaty lapsed in 1866 and the licensing of American vessels was now being rigorously enforced [see Peter Mitchell]. Solving this issue became a matter of vital importance to Great Britain, which hoped to face the military and political consequences of the Franco-German War without the distraction of Americans being angry and belligerent. The United States, Macdonald told Tupper, wanted everything and would give nothing; his British colleagues, especially Lord de Grey, the chief commissioner, were ready to make Macdonald and Canada responsible for failure. They wanted a treaty in their pockets “no matter at what cost to Canada.” Macdonald seriously weighed resigning as commissioner. De Grey strongly urged him not to, for the resignation of a plenipotentiary, especially the Canadian one, would endanger the treaty in the American Senate. Macdonald had been caught, as he admitted, between the devil and the deep blue sea, between his roles as a British commissioner and as Canadian prime minister. Britain was so anxious to secure a treaty that, to help persuade Canada to ratify it, the British accepted Macdonald’s suggestion that compensation be given by the imperial government for the Fenian raids, since the Americans had refused to consider any redress as part of the treaty.

Ratification of the Treaty of Washington

Americans had accepted Canadian ratification of the treaty only because they thought that Canada would be a rubber stamp. If the British parliament ratified the treaty, that was that. As Macdonald put it to Tupper in April, “When Lord de Grey tells them that England is not a despotic power & cannot control the Canadian Parlt. when it acts within its legitimate jurisdiction, they pooh! pooh! it altogether.” On 8 May, with much misgiving, Macdonald signed the Treaty of Washington.

In Canada he would face strong opposition from both political parties. He wrote to Rose some days after the signing, “I think that I would have been unworthy of the position, and untrue to myself if, from any selfish timidity, I had refused to face the storm. Our Parliament will not meet until February next, and between now & then I must endeavour to lead the Canadian mind in the right direction. You are well out of the scrape.” He put it more sharply to de Grey: Canadian indignation in June and July was intense and pervaded all classes – parliament was certain to reject the treaty. If that happened, Macdonald suggested to Governor General Baron Lisgar [Young*] in July, he would leave the government. His colleagues might or might not carry on without him. If they resigned, and a Liberal government were formed, it would oppose the treaty lock, stock, and barrel.

The fall of the Sandfield Macdonald government in Ontario in December 1871 did not augur well for the treaty, or for Ontario in the next federal election. Edward Blake*, the new premier, and Alexander Mackenzie, his lieutenant, both opposed the treaty. It offered Ontario and Quebec nothing: no compensation from the United States for the Fenian raids on the Ontario and Quebec borders; free navigation of the St Lawrence for the Americans in return for the dubious privilege given to Canada of navigating three rivers in Alaska. The fisheries settlement offended most areas: Canadian fish would be admitted free to the American market, but access to the inshore fisheries was to be sold to the Americans for 10 years at a price to be set down by arbitrators. Macdonald had had to fight to avoid it being set down for 25 years. Scholars could later write about the treaty as an achievement in settling outstanding issues between Great Britain and the United States; it was another matter for the prime minister of a country that had to swallow critical sections of it. In the end, by waiting until May 1872, when Canadian public opinion had cooled down and the British had offered a guarantee for Canadian railways as compensation for the Fenian raids, Macdonald was able to get the treaty through the commons by 121 votes to 55. The vote did not mean, however, that the hustings had forgotten it.

Nor was this all. Riel would not go away. He had been got out of the country, but he drifted back. In the so-called Fenian attack across the Manitoba border in October 1871, Macdonald suspected him of playing a double game, first encouraging the leader, William Bernard O’Donoghue*, and then switching sides when he saw that the raid would be damped down by the Americans. For this and other reasons, Macdonald found Lieutenant Governor Adams George Archibald’s shaking hands with Riel in apparent reconciliation unpardonable, and he wished that Archibald had had his political antennae sensitized by Ontario’s reaction to the death of Thomas Scott.

Election of 1872

These elements combined to make the general election of the summer of 1872 difficult, even treacherous, for Macdonald. He did not like to run a government out to full term, but after Washington an election in 1871 would have been folly. Even now the timing was not much better. Ontario farmers, he told Colonial Secretary Lord Carnarvon privately in September 1872, could not understand why the Maritime provinces should get free admission of fish to the United States while Ontario got nothing. And Ontario was even more important politically than before; after the 1871 census, redistribution gave it 88 seats, six more than it had in 1867. Macdonald worked at Ontario tenaciously. He went nowhere else (it was still the custom for ministers to preoccupy themselves with their home provinces), leaving Quebec to Cartier and Langevin, New Brunswick to Tilley, Nova Scotia to Tupper, and Manitoba to A. G. Archibald and Gilbert McMicken, now dominion lands agent in that province. Macdonald also lavished money on Ontario. He got $6,500 from Conservative friends and received from Sir Hugh Allan* some $35,000, plus an emergency draft of $10,000 on 26 August. The day after, in Toronto, he borrowed $10,000 on his own hook from Charles James Campbell and John Shedden* at six per cent on a six-month note, a loan that alarmed Conservative campaign manager Alexander Campbell.

By this time Macdonald was very discouraged. He fought on as best he could, with those reserves of optimism that he always summoned up when the going was bad. His modus operandi in Ontario is suggested in his dealings with James Simeon McCuaig, mp for Prince Edward: “Let me tell you that if [Walter] Ross goes in with money he will stand a great chance of beating you. You must fight him with the same weapon. Our friends here have been liberal with contributions, and I can send you $100000 without inconvenience. You had better spend it between nomination and polling.” McCuaig lost, and Macdonald got only 42 out of 88 Ontario seats, if that. In September he estimated his overall majority as 56. That was high, though how big his majority was depended on the issue. In April 1873, when Lucius Seth Huntington* broke the first intimations of the Pacific Scandal, it would be 31.

Fall of the government, 1873

Canadian Pacific Railway

At least three, possibly four, groups in Canada were interested in the Pacific railway by 1872, to say nothing of Americans. The main groups were those of Sir Hugh Allan of Montreal and David Lewis Macpherson of Toronto. Cartier had conceded in 1871, under opposition pressure and while Macdonald was ill, that the railway would not be built as a government enterprise but by a private company. Macdonald tried to bring the main groups together before, during, and after the election, but jealousies between Toronto and Montreal and mutual suspicions between principals made that impossible. In the late autumn of 1872 Allan was given the task of putting a company together to build the railway. Macdonald had made only one promise to Allan: the presidency of an amalgamated Canadian Pacific Railway Company, whenever it was formed. But there were commitments of which, as yet, Macdonald knew nothing, notably Cartier’s to Allan in the summer of 1872, that Allan’s group would be guaranteed the charter and a majority of stock in return for additional election funding, totalling more than $350,000. When Allan finally told Macdonald the amount, it seemed so fantastic that he did not believe Allan, and that fall he wrote to Cartier to confirm it. Cartier did, more or less; he was then in London fighting Bright’s disease, which eventually would kill him, in May 1873. There was also Allan’s commitment to American backers, of which Macpherson had been suspicious all along.

Pacific Scandal

The Pacific Scandal was partly scandalous, partly not. All parties used money at election time. Macdonald would explain to Governor General Lord Dufferin in September 1873 how Canadian elections went. There were legitimate election expenses; because of the many rural constituencies, with sparse populations, these were large. Other expenses, long considered necessary, were in a half-light, being sanctioned by custom though technically forbidden by law – for example, hiring carriages to take voters to the polls. Such expenses, in Macdonald’s parliamentary experience, had never been pressed before an elections committee. No doubt the $1,000 McCuaig was to spend between nomination and polling day was partly for carriages. It was also no doubt for other things Macdonald did not mention: treating the voters could comprehend more than just carriages and whisky.

The Pacific Scandal broke in the commons on 2 April 1873. Huntington made a motion calling for a committee of inquiry and charging that Allan’s original company, the Canada Pacific Railway Company, had been financed with American money and that Allan had advanced large sums of money to senior members of the government in the election. To his charges Macdonald ostensibly paid no attention; he brought in the members and voted down Huntington’s motion; he called for a committee of investigation on his own. However, Conservatives were already uneasy. From then on Macdonald fought a stubborn, sometimes despairing, but often skilful rearguard action, hoping to rally his followers and to placate an uncomfortable, occasionally censorious governor general. But the telegrams published in Liberal newspapers on 18 July were damning, showing that Macdonald, and especially Cartier and Langevin, had accepted large sums of money, actions that were singularly inappropriate since the funds came from a financier with whom the government was negotiating a major railway contract.

When parliament met in late October, Macdonald’s colleagues were confident they would weather the storm, but almost at once defections began, including that of Donald Alexander Smith. Macdonald was urged to meet the opposition, to stop further haemorrhage while there was time. Dufferin and others believed that had the prime minister forced a vote of confidence early enough, he might have won by double figures. But Macdonald sank into a lethargy of gin and despair, waiting, glassy-eyed, for some card he feared the opposition had up their sleeve. Finally, he made a great rallying speech on the night of 3 November, but he had been outgeneralled by fear and had left it too late. He and his government resigned 36 hours later, on the 5th.

Leader of the opposition

Macdonald was in some ways glad to be out of it. He went to caucus the day after his resignation and offered to retire as leader, half hoping the members would accept, half fearing an abrupt plunge into private life. Caucus would have none of it. Perhaps retirement was not in his nature. When he was ill in 1870, Joseph Howe had suggested that he should retire to the bench, as chief justice of the proposed supreme court of Canada [see Sir William Johnston Ritchie]. Macdonald was contemptuous, exclaiming as Under-Secretary of State E. A. Meredith recorded in his diary, “‘I wd. as soon go to H–ll!’”

Shortly after New Year’s Day 1874, the new government of Alexander Mackenzie called an election and proceeded to wipe the floor with the Tories. Of 206 seats in the house, the Liberals took 138. Macdonald held Kingston, by only 38 votes, but he was unseated in November on charges of bribery and other electoral malpractice. Yet the Conservatives’ popular vote overall, even in this disastrous election, was still 45.4 per cent. Now in opposition (he was returned in a Kingston by-election), Macdonald needed income to live on. The money acquired in 1872 had never stuck in his pockets; he had bled freely with his own money, as well as with the funds of Allan, C. J. Campbell, Sir Francis Hincks*, and others. He was only five years distant from having been flat broke.

Personal life

Daughter’s birth and disability

Macdonald’s private life in the 1850s and 1860s had demanded all his reserves of patience and sanguineness, hope and resilience. The spring and summer of 1869 marked its nadir. After a long and dangerous delivery, Agnes gave birth on 8 Feb. 1869 to a hydrocephalic girl, Margaret Mary Theodora, whose enlarged head undoubtedly contributed to the difficulty of her birth. A photograph taken in June shows Agnes and Mary; sad it is. Even sadder is one of mother and daughter in 1893 when Mary was 24. The cost in moral anguish to both parents can never be known, but any judgement of Sir John and Agnes should always have Mary in mind. By midsummer 1869 it was slowly coming to Macdonald – and with what infinite reluctance did he allow it – that Mary might never be normal. There were always hopes of some new medical treatment that would allow her to live like anyone else. It never came. She never did.

Financial problems

In 1869, too, Macdonald hit the bottom of his personal finances. He had been fighting off that dénouement for five years. One reason for the elaborate marriage settlement of 1867 was to protect Agnes against his creditors. The problem had begun in March 1864 on the death of his law partner, A. J. Macdonell. In May 1867 an estimated $64,000 (roughly $1.8 million in 2024 prices) was jointly owed by Macdonald and the Macdonell estate, mainly to the Commercial Bank of Canada. As long as it would carry him – at rates of interest as high as seven per cent – Macdonald could stay afloat. But in September the bank failed; its assets and liabilities were taken over by the Merchants’ Bank of Canada. Among the assets was Macdonald’s debt, which in April 1869 was almost $80,000. Hugh Allan, president of the Merchants’ Bank, did not press but indicated, when Macdonald raised the matter, that it would be useful to have the debt dealt with. The arrangements Macdonald was compelled to make in 1869 are by no means clear. He borrowed $3,000 from D. L. Macpherson to tide him over and, with Agnes, took out a mortgage on property at Kingston, payable to the bank, for $12,000. The money owed him by the Macdonell estate was largely uncollectable. (When Macdonell’s widow died in 1881, Macdonald’s Kingston factotum, James Shannon, told him that the estate still owed him $42,000.) In 1869 a case was pending in Toronto against Macdonell and Macdonald. It could have been settled out of court in 1865 for $1,000, but Macdonald did not like the counsel for the plaintiffs, Richard Snelling, whom he thought a shark. Finally Hewitt Bernard, again acting as a personal aide, was forced to negotiate a settlement in 1872, for $6,100.

At the time of confederation Macdonald had little income. As prime minister and minister of justice, he earned $5,000 per year. His income from his legal partnership with James Patton Sr of Toronto, formed in 1864, was $2,700 between 1 May 1867 and 30 April 1868; the next year it was $1,760. What got Macdonald through was pride, and his friends. Macpherson discovered how bad Sir John’s position was after Macdonald’s attack of gallstones in May 1870; he set to work to develop a private subscription. He thought it unjust that a prime minister could not support and educate his family on his official income. In the service of his country he had become poor. By the spring of 1872 some $67,000 had been collected by Macpherson and invested as the Testimonial Fund, the income of which Macdonald could use in meeting the ordinary costs of living. Out of it, presumably, Macdonald’s debt to the Merchants’ Bank would be slowly discharged. Ever sanguine, in 1876 he told Thomas Charles Patteson of the Toronto Mail not to be upset at owing money. Treat debts as Fakredeen, in Disraeli’s Tancred, treated his, Macdonald advised: he “caressed them, toyed with them. What would I be without these darling debts.”

Relocation to Toronto

After the parliamentary session of 1874 was over, Macdonald began to feel that perhaps his fighting days were coming to an end. He sold his Ottawa house in September 1874 for $10,000 and began plans to move to Toronto, where his law firm and principal client, the Trust and Loan Company, were now located. Before he moved, he wanted the dispute over the contested Kingston election settled; he did not want it known that he would not be returning to Kingston. He won the by-election at the end of December by 17 votes. He then moved into a house on Sherbourne Street in Toronto, rented from T. C. Patteson, and a year later into a more fashionable brick house on St George Street.