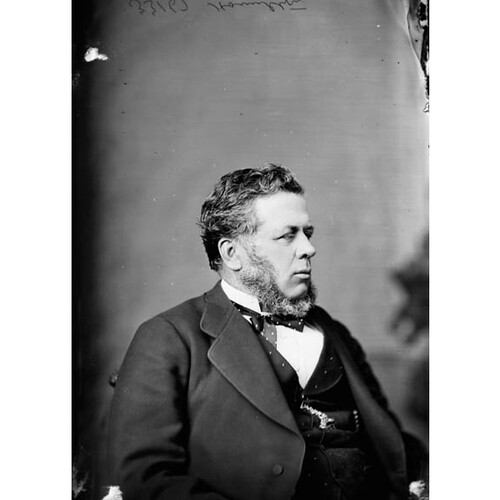

HAMILTON, JOHN, lumberman, financier, and politician; b. 16 Dec. 1827 at Hawkesbury, Upper Canada, son of George Hamilton* and Lucy Susannah Christina Craigie; d. 3 April 1888 in Montreal, Que.

John Hamilton’s father, one of the most successful early lumbermen in the Canadas, bequeathed to his sons upon his death in 1839 a large, integrated timbering operation, including numerous timber berths, mills at Hawkesbury, and his own timber cove at New Liverpool, Lower Canada. In 1843, after completing his education in Montreal, John Hamilton entered the lumber trade with his two elder brothers, Robert and George Jr.

A new partnership, called Hamilton and Thomson, was formed at this time with John Thomson, former manager of John Caldwell*’s Etchemin Mills Company, and his sons Andrew* and John. Robert Hamilton became the firm’s permanent agent in Quebec City and supervised the New Liverpool timber cove, while John Hamilton learned the milling business in Hawkesbury. The new company produced squared pine and oak as well as pine deals for the British market. Timber was acquired from limits along the lower Ottawa River and from the Gatineau, Rideau, Rouge, and South Nation rivers, and this supply was supplemented by wood bought from smaller contractors at the Hawkesbury mills. Hamilton and Thomson quickly expanded its operations by purchasing L. G. Bigelow’s mill on the Rivière du Lièvre, and with these new facilities the company was able to take a dominant part in the timber trade.

Around 1849 the Hamiltons bought out the Thomson interest in the business and Robert, George Jr, and John set up a new partnership called Hamilton Brothers. At this time John Hamilton took over sole responsibility for the management of the up-country cutting operations and the milling activities at Hawkesbury and on the Rivière du Lièvre. Thus established, he married Rebecca Lewis in 1852. During the late 1850s the company continued to acquire new limits at Rapides des Joachims on the upper Ottawa in Canada East and along the Dumoine and Noire rivers. In 1860 R. G. Dun and Company appraised the firm’s worth at between $320,000 and $400,000, and by 1871 its production had climbed to 40 million board feet of pine annually, amounting to nearly $550,000 worth of business. After Robert Hamilton’s death in 1872 John carried on alone and the company remained the principal basis of the Hamilton family’s wealth until it was sold in 1888.

John Hamilton had inherited more than a business from his father. He had also been inculcated with George Hamilton’s staunch ultra-Tory views and his intense and partisan interest in public affairs. Such an interest he amply demonstrated in 1858 when he was elected as Hawkesbury’s first reeve. Hamilton remained reeve until 1864, and served as warden of the United Counties of Prescott and Russell three times. In 1860 he was elected for the Inkerman division (counties of Argenteuil, Ottawa and Pontiac, Canada East) to the Legislative Council supporting the Conservative ministry of George-Étienne Cartier* and John A. Macdonald*. Hamilton tried to establish himself as a political power in “the Ottawa country,” but was not particularly successful in his endeavours. He greatly resented the influence which Richard William Scott*, member of the Legislative Assembly for Ottawa City, wielded with the government, especially with the Crown Lands Department, in policy and patronage matters. After the administration’s defeat in 1862, Macdonald used Hamilton as a rallying point amongst the Ottawa valley lumber community for Conservative support against John Sandfield Macdonald*. For services rendered at this time Hamilton was appointed to the new Canadian Senate on 28 Oct. 1867.

Hamilton’s political prestige began to wane considerably after confederation. The Conservative party in the Prescott County area was divided into two factions: English-speaking individuals, with whom Hamilton was closely associated, and French-speaking. The rapidly growing French Canadian population in Prescott forced Hamilton to enter into an agreement in 1867 with the parish priest, Antoine Brunet, stipulating that the Conservatives would endeavour to elect a French Canadian to the House of Commons and an English-speaking member to the Ontario legislature. Because of party considerations Hamilton was forced to give his support to Thomas D’Arcy McGee* as a candidate in Prescott for the first Ontario legislature. The Protestants, annoyed by Hamilton’s agreement with Brunet, were further alienated by his assistance to an Irish Catholic, and he finally found it necessary to support the minority English-speaking Conservative group over the majority French-speaking group. Hamilton’s agreement with Brunet was respected at the provincial level, so that an English Canadian went to the assembly, but from 1867 until 1878 an English Canadian was also elected for Prescott to the House of Commons. When a French Conservative, Félix Routhier, was elected federally in 1878 despite Hamilton’s open opposition, his influence among the English Canadian Conservatives was destroyed.

Finding his political power base being eroded and himself somewhat “off the political track,” Hamilton had been turning to other interests after confederation. In 1869 he was appointed colonel of the 18th (Prescott) Battalion of Infantry in Prescott and he took a lively interest in local and national militia matters. It was, however, his involvement in an ever widening group of corporate and financial ventures which diverted Hamilton’s attention from immediate political affairs. During the 1860s and early 1870s he earned a reputation as a sound businessman not only for his management of Hamilton Brothers but also as a director of several transportation companies closely related to the lumber industry, including the Union Forwarding and Railway Company, the Canada Central Railway, the North Shore Railway, and the St Maurice Navigation and Land Company. Hamilton’s business reputation was complemented by his prestige as a senator; he became involved in other corporate enterprises, and made a concentrated effort to establish himself in the Montreal financial community by accepting in 1872 directorships in the Reliance Mutual Life Assurance Society of London, the Canada Investment and Agency Company, and the Coldbrook Rolling Mills Company of Nova Scotia.

The key to John Hamilton’s success in these new areas of business was his association with the Merchants’ Bank. It had been founded in 1861 by Hugh Allan (president from its opening in 1864), Andrew Allan*, Edwin Atwater*, and Louis Renaud*, among others; both John and his brother Robert had bought shares in the bank and used its credit to finance their own business activities. In 1874 John was elected to the board of directors, and the following year was honoured with the vice-presidency. Hamilton, however, was not completely happy with his new situation. The depression which followed the economic crash of 1873 weighed heavily on Canadian business, and the Merchants’ Bank was particularly vulnerable. While quickly increasing its capital, the rapid expansion in business had also brought the bank questionable Detroit and Milwaukee Railway bonds acquired with the take-over of the Commercial Bank in 1868, losses in floating a Quebec government loan in London, losses in the New York gold market, and numerous bad or doubtful debts at home, which now threatened to pull it under. As early as the annual meeting of 1874 concern was expressed regarding circulation and deposits not keeping pace with the bank’s increase of capital. As well Hamilton himself suspected that the Allans were using the bank for their own speculative purposes and not for the good of the institution. The matter came to a head in early 1877 when, because business conditions were not improving, a special meeting of stockholders was called to discuss the affairs of the bank. As a result Jackson Rae, the Merchants’ general manager, resigned on 21 February, and a day later Hugh Allan stepped down as president.

At this crucial point John Hamilton, as vice-president, took over direction of the affairs of the second largest bank in Canada and was named president. George Hague, the recently retired general manager of the Bank of Toronto, was persuaded to take over the management of the troubled institution and his full investigation, confirmed by a committee of Hamilton, his vice-president, and Hugh Allan (who had continued as director), revealed that the bank faced losses totalling nearly 3 million dollars. Hague imposed harsh retrenchment policies, such as the elimination of operations which showed losses in New York and London as well as of unprofitable branches at home, and rebuilt the bank’s internal structure. The directors guaranteed a 1.5 million dollar loan from the Bank of Montreal and the Bank of British North America, and Hamilton went to the banking committee of the federal parliament with a proposal to devalue each of the bank’s shares by 25 per cent: the act, which reduced the capital stock from nine to a little more than six million dollars, was passed in early 1878. With this help and Hague’s expert management the bank was back in excellent shape by 1882. That year, at the annual meeting of 21 June, Hamilton, with some bitterness, surrendered the presidency to Huge Allan, who had once again captured the support or the majority of directors and shareholders.

John Hamilton’s handling of the Merchants’ Bank affair earned him high esteem throughout the entire Canadian business community. In 1884 he was invited to join the powerful and illustrious group which formed the board of directors of the Bank of Montreal. He accepted this position gladly and the influence and prestige it bestowed enabled him to divest himself of all his other business duties, except his interest in the management of Hamilton Brothers. He even resigned as president of the Canada Timber and Lumber Association, a position he had held since 1876. Once again he had reached a turning-point in his life. Putting behind him the bustle of Montreal finance, he devoted a great deal more time to the Hawkesbury mills and his family concerns. Indeed his domestic life had been extremely active. Rebecca Hamilton had died during the early 1860s and John had remarried. When his second wife, Ellen Marion Wood, died in January 1872 he married, on 3 June of the same year, a widow, Jean Major. From his first two marriages a family of three sons and five daughters survived to adulthood; its activities were centred at Evandale, his island estate, and long his chief residence, near the Hawkesbury mills, and at his Montreal home, Tyrella House.

Hamilton retired honourably from the Senate early in 1887 when his seat was needed for his old friend, John Joseph Caldwell Abbott*, whom Sir John A. Macdonald wished to become government leader in the upper house and a member of the Privy Council. Hamilton was not loath to step down since he had never found the satisfaction in politics he had hoped would be forthcoming and he was beginning to despair of politicians ever finding the solution to Canada’s grave economic problems. Unfortunately he did not live long enough to enjoy his more relaxed pace of life; on 3 April 1888 at 60 years of age, John Hamilton died at his home in Montreal.

AO, MU 1197–223. PAC, MG 24, D7; MG 26, A, 222; MG 29, E24; RG 31, Al, 1871, Prescott sub-district and Hawkesbury village. Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1854–55. Chadwick, Ontarian families. CPC, 1871–84. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1886). List of the shareholders of the Merchants’ Bank of Canada as of 1 June 1882 (Montreal, 1882). Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, III. Atherton, Montreal, III. Lucien Brault, Histoire des comtés unis de Prescott et de Russell (L’Orignal, Ont., 1965). M. S. Cross, “The dark druidical groves: the lumber community and the commercial frontier in British North America, to 1854” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1968). J. E. Defebaugh, History of the lumber industry of America (2v., Chicago, 1906–7), I: 134, 537. Denison, Canada’s first bank. S. J. Gillis, The lumber trade in the Ottawa Valley, 1806–54 (Ottawa, 1975). R. M. Breckenridge, “The Canadian banking system, 1817–1890,” Canadian Banker, 2 (1894–95): 105–96, 267–366, 431–502, 571–660. Shortt, “Hist. of Canadian currency, banking and exchange: some individual cases,” Canadian Banker, 13: 272–88.

Cite This Article

Robert Peter Gillis, “HAMILTON, JOHN (1827-88),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_john_1827_88_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_john_1827_88_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Peter Gillis |

| Title of Article: | HAMILTON, JOHN (1827-88) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |