Source: Link

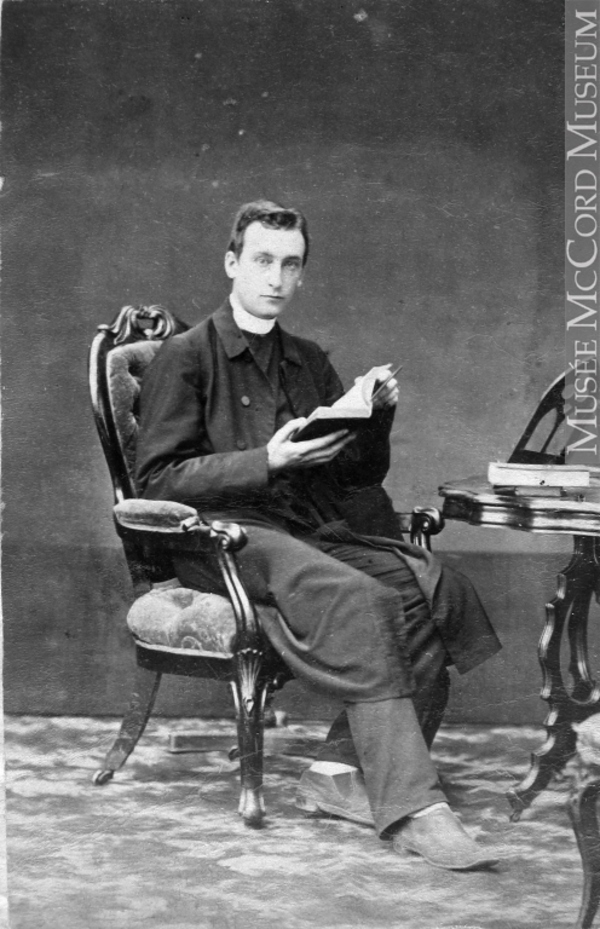

WOOD, EDMUND, Church of England priest and educator; b. 27 Feb. 1830 in London, England, son of William Wood and Anne Aston Key; d. unmarried 26 Sept. 1909 in Montreal.

Edmund Wood was educated at Turrell’s School, Brighton, and at University College School, London, where an uncle was headmaster. He entered St John’s College, Oxford, but, owing to his family’s fnancial misfortunes, quickly transferred to the less expensive University College, Durham. Years later he referred to these misfortunes as “the unhappy events of 1849 . . . [causing] a wound which time will never wholly heal.” From University College Wood received a ba in 1854 and an ma in 1857.

In Durham he became friendly with the Reverend John Grey, the rector of Houghton-le-Spring and “a leader of the High Church party in Durham Diocese,” who nominated him for the position of curate in his parish. With this assurance of preferment, Wood was made deacon in 1855. Over the next three years he served at Houghton-le-Spring, paying particular attention to the poor pitmen of the coal districts and, in early 1858, arousing the concern of his bishop over charges of “popery” from some parishioners. Meanwhile, his family had immigrated to Lower Canada and in 1857 his father died in Montreal. These events, combined with the suggestion of the Reverend William Bennett Bond of St George’s Church, Montreal, that he take up service in the diocese of Montreal, led him to resign his curacy and go to Lower Canada. He arrived in Montreal in November 1858.

The bishop of Montreal, Francis Fulford*, immediately appointed him junior assistant at the pro-cathedral and assigned him to minister to the poor in the southeastern part of the parish. There he was to devote the rest of his life to a work of worship and service that would meet with fierce opposition from many clergy and laity for some years but that would be rewarded by wide and enthusiastic commendation shortly before his death. In July 1861 he was ordained priest by Fulford.

The original centre of Wood’s mission work was an old stone mortuary chapel in the Protestant burying ground at what is now Dufferin Square. Permission to use this homely and decrepit building had been obtained by Fulford with the help of judge John Samuel McCord. McCord’s son, David Ross, later recorded that when the bishop and Wood first opened the chapel door they were assailed by a nearly overpowering odour of decay. “The Bishop, his nostrils twitching uncertainly, turned and remarked, ‘Do you not think, Wood, a little incense would be appropriate.’” Prophetic words indeed.

In Lower Canada Wood quickly put himself in the forefront of a liturgical and pastoral renewal that was already under way in England. The building was put in order, roughly furnished, and opened for services. Seats were provided free of charge and pastoral work concentrated on the poor. The congregation so grew in size that in summer the windows were opened and twice as many people as were inside would sit on the grass outside and take part in the services. There, the first choral evensong in Montreal, if not in Canada, was sung by Wood on Christmas Eve 1859.

A new building was soon needed. Once again, Fulford came forward to help. A successful appeal for funds was made throughout the Canadas and England, a lot was acquired at the corner of Saint-Urbain and Dorchester (Boulevard René-Lévesque), a new edifice was completed in March 1861, and for the first time since its establishment the mission had a name, St John the Evangelist. Weekly and daily choral services were begun. The ceremony of the liturgy was enhanced through a surpliced choir, altar candles, and a prominent cross on the altar.

These so-called Tractarian innovations were not appreciated by many in the diocese, and especially not by the Reverend Ashton Oxenden*, who succeeded Fulford as bishop of Montreal and metropolitan of the ecclesiastical province of Canada in 1869. The first crisis came when Wood’s curate, the Reverend Augustus Prime, unwisely circulated a few copies of a pamphlet entitled A rule of life at the diocesan synod of 1871, a meeting Wood later described as “that dreadful Synod.” The pamphlet, printed in England, seemed to advocate the doctrine of transubstantiation and such practices as prayers for the dead and private confession, all of which exceeded what was permitted by the Book of Common Prayer. Its content was enough to spur the evangelicals in the church to the most intolerant denunciation of Wood and his work.

Oxenden, of definite evangelical leanings himself, was deeply disturbed and Wood was put in a difficult position since, although he did not agree with everything in the pamphlet, he also did not find it “contrarient to the tone and teaching of the Church.” A restrained and carefully worded exchange of correspondence between Wood and Oxenden ended with the suspension of Prime and the publication by Wood of The catholic and tolerant character of the Church of England, which contains copies of his correspondence with Oxenden, a reprint of A rule of life, and his succinct and able commentary on it. Prime’s suspension was lifted after six months.

Despite these events, or perhaps partly because of them, the congregation of St John the Evangelist continued to grow as the reverence of its services, the beauty of its music, and the unremitting care of its pastor became widely known. By 1874 a larger building was needed. A lot was purchased at Saint-Urbain and Ontario, and the foundation-stone of a new building was laid on 20 June 1876 by Oxenden. In the face of many financial and other difficulties the basement of the new church was opened for worship on 6 March 1878. Over the next few years it was completed, and it still stands as a place of Anglo-Catholic worship in Montreal.

Meanwhile, relations between Wood and his bishop reached another crisis in 1876. In part, no doubt, because of continuing pressure from many evangelicals in the diocese, Oxenden in his address to synod that year mentioned “certain unusual divergencies in the mode of conducting the ritual of public worship in one of our churches,” unquestionably a reference to St John the Evangelist. He added that a desire had been expressed “to propose the enaction of some Diocesan Canon in the way of restriction.” But, he concluded, “I would most earnestly deprecate any diocesan legislation on so important a matter.” There was none.

Wood did not handle this situation at all well, probably because it occurred at a time when the burden of his ongoing ministry and the building of the new church had pushed him to the edge of prudence. At synod, he did not speak in his defence, nor did any of those who were undoubtedly in sympathy with him. Subsequently, he returned unopened a letter from the bishop and then, strangely enough, he wrote a letter to his churchwardens requesting them to forward it to the bishop. As the Reverend Charles Hamilton (whose brother John* had married Wood’s sister) pointed out to him in a frank but gentle note, Wood owed it to himself to apologize to the bishop and this he doubtless did, since they eventually came to have a cautious regard for each other. In 1897 Wood would be appointed a canon of Christ Church Cathedral.

By the 1880s Wood’s reputation as a spiritual counsellor, an unremitting advocate of the use of music and ceremonial to enrich the liturgy, and an initiator of a daily Eucharist was becoming widespread. He corresponded with clergy in most parts of Canada, had become vicar general for Canada of the Confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament (formed in 1862 in England to restore the Eucharist to its proper place in worship and to deepen the spiritual life of Anglicans), and founded a society for the study of sacred choral music in his parish. In 1880 he brought in a renowned Anglo-Catholic priest from England, his long-time friend the Reverend Alexander Heriot Mackonochie, who visited St John the Evangelist for two days in spite of his ill health.

From the beginning of his ministry in Canada, Wood had seen the education of the young as an important part of his parochial responsibility. Thus, in 1860 a small school was organized and Wood served as both teacher and headmaster. At the suggestion of Mary Fulford, wife of the bishop, it concentrated on the children of poor families, irrespective of creed or denomination, for whom additional care and encouragement was necessary. A system of regular visits to indifferent parents was established and proved exceptionally helpful. But money and suitable premises for the school were a constant problem. In a few years what came to be called St John’s School seemed to be divided into three parts: a parochial school for the poor, a grammar school, and a choir school.

Although it experienced recurring crises, St John’s continued to grow. Wood, with the assistance of his curates, devoted a significant part of each day to administration and to teaching, giving religious instruction to Church of England students, and music lessons to choir scholars. In 1879 the Reverend Arthur French became headmaster but Wood, as rector, continued to have overall responsibility and to teach. By 1895 the school had 70 students (of whom 27 were resident) and nine teachers. It remained under Wood’s direction until his death, when it moved to another location and became Lower Canada College.

Father Wood, as he had been known for years, was a man who combined, unusually, a lack of prominence in the public eye with the appearance of being better known and of wielding greater influence for good than even the most powerful person. Frederick George Scott*, assistant master at the school in 1884–85, later commented, “There is no [Anglican] church in Canada that has not learned something from the standard of worship set by Father Wood.” “In the death of Mr. Wood,” said John Cragg Farthing*, bishop of Montreal, at the beginning of his address to synod in February 1910, “the Canadian Church lost one of her best known and most honoured priests. Such a life as his is witness to the fact that ‘sacrifice alone is fruitful.”‘

Edmund Wood is the author of The catholic and tolerant character of the Church of England; is it to be maintained? . . . (Montreal, 1871) and A word with his people, about the cross carried before the choir in St John the Evangelist Church, Montreal (Montreal, 1876).

AC, Montréal, État civil, Anglicans, Church of St John the Evangelist, 29 Sept. 1909. AP, Church of St John the Evangelist, Corr. of Edmund Wood, newspaper clippings, notices, and pamphlets. Greater London Record Office, St Alban the Martyr (London), RBMB, 27 Feb. 1830. Univ. of Durham, Eng., Dept. of Palaeography and Diplomatic, DDR, O.P. 1855 (ordination papers). Gazette (Montreal), 23–24 Aug. 1880; 12 Feb., 27, 30 Sept., 27 Nov. 1909. J. D. Borthwick, History of the diocese of Montreal, 1850–1910 (Montreal, 1910). Canadian Churchman, 2 Oct. 1909. Austin Caverhill, “A history of St John’s School and Lower Canada College” (ma thesis, Macdonald College, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Que., 1961). Church of England in Canada, Diocese of Montreal, Proc. of the synod (Montreal), 1868, 1876–77, 1882–86, 1889–90, 1895, 1910. Church of St John the Evangelist, Annual report and year book (Montreal), 1885; Centenary book of the parish of St John the Evangelist, Montreal, 1861–1961 (Montreal, [1961]); A historical record in commemoration of the jubilee of the parish church, ed. W. H. Davison (Montreal, [ 1928]); Parochialia (Montreal), 1 (1879); 3 (1881). “Laying the foundation stone of the free church, Montreal,” Church Chronicle for the Diocese of Montreal (Montreal), 1 (1860–61): 49–51. D. S. Penton, Non nobis solum; the history of Lower Canada College and its predecessor, St John’s School (Montreal, 1972).

Cite This Article

J. P. Francis, “WOOD, EDMUND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_edmund_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_edmund_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. P. Francis |

| Title of Article: | WOOD, EDMUND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |