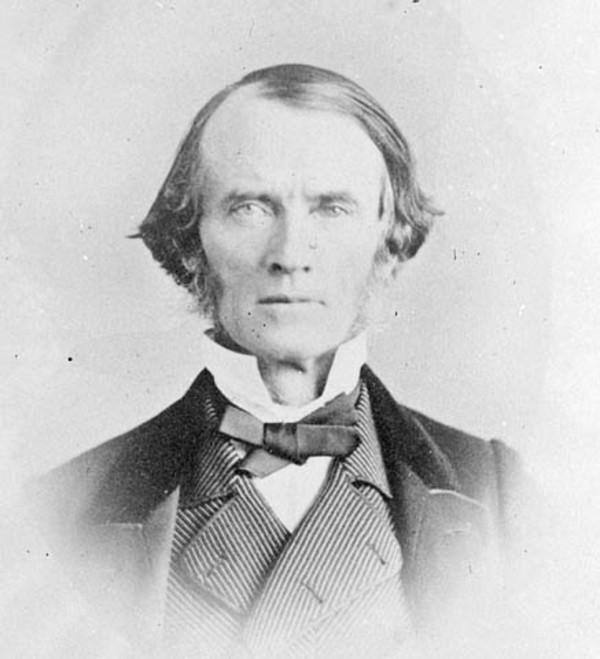

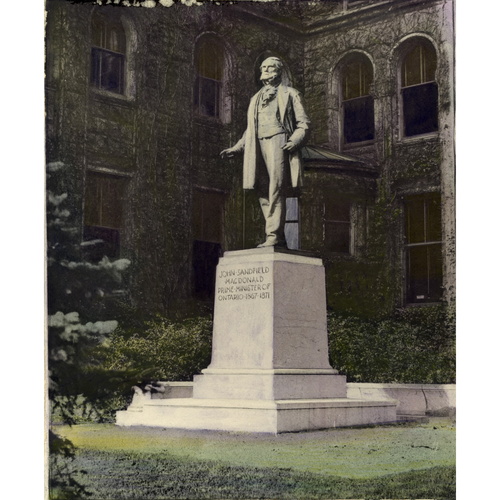

MACDONALD, JOHN SANDFIELD, lawyer and politician; b. 12 Dec. 1812 at St Raphael West, Glengarry County, U.C.; d. 1 June 1872 at Cornwall, Ont.

John Sandfield Macdonald’s father, Alexander, was a Roman Catholic Highland Scot of Clan Ranald. As a child Alexander had emigrated in 1786 with other Catholics from Scotland to settle in what was to become Upper Canada. He married Nancy Macdonald, the daughter of a distant cousin, and John Sandfield was the first of their five children.

Left without a mother at eight, Sandfield developed the independent and undisciplined character that marked his future political career as an “Ishmaelite.” He seemed to dislike the confines of the parish school, attending it only for a few years and, at 16, he took his first job as a clerk in the general store in Lancaster. Later, he had a similar position in Cornwall.

Discontented with his prospects after several years as a clerk, Sandfield was encouraged by a local lawyer to enter the legal profession. In 1832 he enrolled in Cornwall’s Eastern District grammar school, the famous training school of the Family Compact, then under the Reverend Hugh Urquhart of the Church of Scotland. Sandfield graduated in 1835 at the top of his class and was articled to Archibald McLean*, a lawyer and leading Tory in Cornwall.

McLean was elevated to the Court of the King’s Bench in 1837, and Sandfield became his assistant on the western circuit. It was a position which enabled Sandfield to meet eminent men of the day, including Allan MacNab*, Thomas Talbot*, and William Henry Draper under whom he later articled. He was also given a commission as queen’s messenger, charged with carrying dispatches between the lieutenant governor in Toronto and the British minister in Washington. On one of these missions the tall, gangling Glengarrian met Marie Christine Waggaman, daughter of George Augustus Waggaman, a former Whig senator from Louisiana originally from the Maryland gentry, and Camille Armault, who came from Louisiana’s old French aristocracy. In 1840 Sandfield opened his own law office in Cornwall and in June of that year was called to the bar. Several months later, Christine eloped from her French finishing school in Baltimore with the adventuresome Scot. They were married in New York City in the fall of 1840.

In 1841 Sandfield was drafted by Colonel Alexander Fraser* and John McGillivray*, respectively the Catholic and Presbyterian political lairds of Glengarry, to stand for election to the first Legislative Assembly of the united Province of Canada. His patrons’ control over the area was such that Sandfield won by a substantial majority over the Reformer, Dr James Grant, without delivering a single political address. Sandfield became known outside his district as a Draper Conservative but had at this point few fixed ideas on politics. He seemed at times closer to the old-line Tory position of Alexander McLean, mla for Stormont and brother of his former tutor, Archibald, particularly when Draper’s municipal reforms threatened the patronage system of Glengarry. Draper placated Fraser by appointing him first warden of the Eastern District, made up of the counties of Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry, and Sandfield secured the privilege of delivering the speech of welcome at Cornwall to the new governor general, Sir Charles Bagot*, and of seconding the address-in-reply at the opening of the session of the assembly in 1842. He was jibed at by the old-line Tories for his alleged betrayal. He believed that it was they who made Draper’s position untenable and he agreed with Bagot’s policies. For these reasons he continued to support the government when it was reorganized along Reform lines with the coming to office of Robert Baldwin*, Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*, Augustin-Norbert Morin*, and others. Moreover, the new council was prepared to serve Glengarry well: a generous provincial grant for district education was obtained and patronage jobs were given to supporters. Sandfield himself became a lieutenant-colonel in the 4th Regiment of the Glengarry militia. Aided by his own and Christine’s flair for entertaining, he was fast becoming his own master in Glengarry.

Sandfield went into opposition on the resignation of the Reform ministers in November 1846, following the dispute with Governor General Charles Metcalfe* over patronage. The Glengarrian thus took the decisive step in affixing to himself the label of Reformer and joined Baldwin’s crusade for responsible government; he was to remain a self-proclaimed “Baldwinite” until his death. Despite Draper’s successful attempt in most of Canada West (still popularly called Upper Canada) in the ensuing election to condemn Reformers as disloyal and inimical to British institutions, Sandfield was easily returned in Glengarry and helped defeat McLean in Stormont.

The tide began to turn to Reform and Sandfield’s influence increased. He had his own weekly newspaper, the Cornwall Freeholder, and won re-election in 1848 despite the intervention of the Catholic bishop Patrick Phelan*, who implied that the faithful should vote for the Tories. The La Fontaine-Baldwin ministry was formed with a majority from both Lower Canada (Canada East) and Upper Canada and responsible government seemed secure. To Baldwin, patronage was its vital concomitant and, in and around Glengarry and Cornwall, Sandfield was its chief purveyor. He supported Baldwin’s municipal reforms in 1849 (although securing the survival of the Eastern District as the United Counties of Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry), and held Glengarry for Lord Elgin [Bruce*] during the crisis over the rebellion losses bill despite Fraser’s objections. Late that same year, he became both a queen’s counsel and Baldwin’s solicitor general for Upper Canada. In 1850 Sandfield’s followers made a clean sweep in the local municipal elections.

Sandfield’s personal fortunes were also rising. He was steadily acquiring property and his legal practice had so expanded that he was forced to hire two assistants. “No barrister,” claimed the Globe, later to be his most insistent critic, “stands higher in the estimation of mercantile men.” In 1849 his family, then including three daughters and a son, moved into Ivy Hall, the stately residence that had once housed the imperial garrison in Cornwall. Later there were two more children.

Once formal responsible government was secure, Reform forces began to disintegrate, and in 1851 La Fontaine and Baldwin resigned. Francis Hincks* tried to reorganize the government and Sandfield now expected to succeed Baldwin as attorney general west. Hincks personally disliked Sandfield, however, considering him too independent-minded, and felt it essential also to regain the support of the Clear Grits, the Upper Canadian radical democrats. Using an unsuspecting Sandfield as a go-between, Hincks succeeded in bringing two Clear Grits into the cabinet and secretly asked William Buell Richards* to be attorney general. Knowing the effect it would have on Sandfield, Hincks wrote him a condescending letter blaming him for the Clear Grit demand for two cabinet positions rather than one. The enraged Glengarrian resigned as solicitor general. He never forgave Hincks for turning him out “to pasture like an old horse.”

Sandfield had become essentially an independent Reformer but, after the elections of December 1851 and his own flattering return by acclamation, he had a considerable following in the assembly from eastern Upper Canada. In recognition of his power and, no doubt, to mute his voice, Hincks offered him the speakership. After considerable hesitation, he accepted. As speaker, however, he was unable to voice his and his constituents’ dissatisfaction with the government’s support of sectarian colleges and separate schools and with its hesitation in abolishing the clergy reserves and other examples of denominational privilege in Upper Canada. In Glengarry, the relationship between Protestant and Roman Catholic Scots was a friendly one. This experience, his own individualism, and the alienation of the Catholic Scots from the church hierarchy, securely in militant Irish hands, shaped Sandfield’s highly secular attitudes toward church and state relations. He was himself only nominally Catholic.

The speaker was also greatly displeased with the profusion of railway scandals, some involving the premier himself. To increase his frustration, he was forced in 1853 to take a rest of six months in Europe because of lung trouble which was to leave him a semi-invalid. While in London, he made a dubious deal by which his brothers, Alexander Francis and Donald Alexander*, were to construct the portion of the Grand Trunk Railway between Farrans Point in Stormont and Montreal.

The speakership was a burden but it gave Sandfield one of his greatest moments. The government did not resign after defeat in the speech from the throne debate at the opening of the 1854 session. Instead of calling for a new ministry Elgin appeared two days after the vote to dissolve the house. Before he could read the closing address, an irate Sandfield delivered a stern rebuke, in English and French, questioning the constitutionality of Elgin’s actions. Dissolution followed, but the outspoken speaker became overnight a popular hero as the defender of the constitution against tyranny. He was returned by acclamation in Glengarry, and George Brown of the Globe even pledged support to any government he formed if it was dedicated to the separation of church and state and to representation by population. Sandfield could hardly have accepted the latter proposition; as a central Canadian with Montreal as his metropolis, he was dedicated to the dual nature of the united province. He believed that government should not be carried on against the wishes of a majority from one or other of its two historic sections.

The election proved inconclusive but it seemed that Sandfield, with the backing of Brown, dissident Reform elements, and moderate Conservatives, would become premier of Canada. This did not happen. Although Hincks was defeated in the house, he and others were able to effect a coalition with the Conservative faction. Elgin summoned MacNab of the Tories, not Sandfield, and Morin and the rest of the Lower Canadian wing of the old government held firm.

Sandfield was left as the leader of a disunited Reform opposition made up of Brown, the Clear Grits, the Rouges or Lower Canadian radicals, Sandfield’s own following, and a few other scattered Baldwinites. Sandfield refused to support Brown’s policies, including representation by population, and relations between them deteriorated during the sessions of 1855 and 1856. Sandfield ceased to be leader of the opposition and their cooperation ended when Brown mounted a scathing personal attack in 1856 against a resolution by Sandfield favouring official endorsation of the principle of the double majority. Brown seemed, meanwhile, to be taking over and absorbing the more radical Clear Grits.

Sandfield’s health was also declining and in 1857 he lost the use of one lung. Because of his weakened condition, he turned over his large rural constituency of Glengarry to his brother Donald Alexander, retaining the riding of Cornwall with its fewer than 700 voters for himself. Both brothers won in the elections of November 1857. With Reform victories elsewhere, the Conservative government failed to gain an Upper Canadian majority. In early 1858, John A. Macdonald*, now premier, offered Sandfield a ministerial post to gain support in the eastern counties. It was doubtful whether Sandfield ever intended to join the government. He took a tough line, demanding for Reformers three of the six Upper Canadian seats. John A. was unwilling to go that far. Sandfield then telegraphed a simple “No Go.”

When the cabinet was defeated in July on the seat of government question, Sandfield reluctantly agreed to serve as attorney general west in the government formed by George Brown. This “most ephemeral government” met defeat in the house and, being refused dissolution, lasted less than 48 hours. The chief Reformers were out of the house seeking re-election, as they were required to do on accepting portfolios, and a somewhat strengthened old gang under George-Étienne Cartier returned through the dubious manœuvre known as the “Double Shuffle.” Sandfield took part in the ensuing opposition tour of the province denouncing the actions of Cartier, John A. Macdonald, and Governor General Edmund Head*, but privately he was convinced that Brown’s impatience to seize office had led to the Reform downfall. To Sandfield, Brown was a leader incapable of getting a Lower Canadian majority to accept him. He could not understand the adulation heaped upon Brown in the western peninsula and once snapped to Charles Clarke*, in Elora: “Can’t you do anything without George Brown . . . ?” Consequently, Sandfield gradually moved closer to Louis-Victor Sicotte* and other members from Lower Canada, who had become alienated from Cartier and might be termed “Mauves,” and farther away from the Free Kirk, Toronto-based, Victorian Liberal George Brown.

The two great Reformers clashed bitterly and personally in 1859 and 1860 in the assembly and in the press over the source of compensation to the former seigneurs of Lower Canada for the loss in 1854 of their casual dues. Was this to come from general revenue or, as Brown claimed he had proposed, from some special levy on Lower Canada alone? In a dualistic country such as Canada, Sandfield argued, Brown could not be a leader, and did nothing now but disrupt Reform and prevent it from achieving power. In all this, Sandfield found a friend and ally in Josiah Blackburn*, influential owner and editor of the London Free Press.

Sandfield also became embroiled in the other major split within Reform. In the spring of 1859, when the Globe was temporarily under the editorial direction of George Sheppard, the paper urged the dissolution of the union and the abandonment of the British parliamentary system for the republican version operating in some mid-western American states. This proposal was as unacceptable to Sandfield as was Brown’s advocacy of the single majority in the assembly. In the fall, Brown called for a great Reform convention in Toronto to reassert his authority and to secure endorsement for “rep by pop” and Canadian federalism. Not happy with conventions, especially those held in Toronto under Brown’s leadership, Sandfield refused to attend and few delegates were present from east of Cobourg. Division continued and, despite Brown’s protestations of strength after the convention, Sandfield argued through the London Free Press that Brown’s followers were the smallest faction of Reform, the dissolutionists second, and the Baldwinites the largest. He was willing to admit that rep by pop was perhaps desirable at some future date if Upper Canada continued to grow, but he emphasized that double majority was more important for harmony, goodwill, and necessary reform.

By March 1860, Sandfield had determined to overthrow Brown as leader of Upper Canadian Reform and began again to attend Reform caucuses. Rumours of a Sandfield-Sicotte alliance increased as both men tried to form closer links with the Rouges and some restless Bleus. They would be “Baldwinite Reformers,” and, like Baldwin, Sandfield argued that, to be viable, Reform had to avoid doctrinaire, sectarian, and sectional stands. The problems of the union were the agitation from the southwestern peninsula and unsuitable men in government, not the constitution.

Sandfield and Sicotte failed in their attempt at reconstruction. Michael Foley*, considered a potential rallying point in the west, succumbed to Brown’s pressure by voting in May 1850 for his resolutions in the assembly declaring the union a failure and calling for a redivision, to be linked by “some joint authority.” Foley attempted to reconcile Brown and Sandfield but their relations grew increasingly bitter. Sandfield stayed away from the caucus during the session of 1861, and continued to cooperate with Sicotte and other sympathetic French-Canadians. A small triumph came when his motion, seconded by Foley, criticizing the government for its failure to have an Upper Canadian majority, narrowly missed acceptance (49 to 64), and helped force the Conservatives to declare the basis of representation an open question. But if Reform was not able to unite on the constitutional question, it could on most non-sectional economic issues. A motion moved by Sandfield and seconded by Antoine-Aimé Dorion*, the Rouge chief, condemning the government for financial mismanagement, failed by only a few votes. Nevertheless, Reform disunity helped the Conservatives in the 1861 elections. Brown was personally defeated and his monopoly on rep by pop destroyed when some Conservatives adopted the programme. The London Free Press bluntly called him a “government impossibility.” Sandfield was again on his way up.

It was true that John A. Macdonald gained in Upper Canada but Cartier lost ground to Sandfield’s ally, Sicotte, in Lower Canada. When 16 more Lower Canadians switched over to Sicotte to defeat Cartier’s militia bill, the governor general, Lord Monck*, summoned Sandfield who had stayed in the background during the defence debate. Sandfield accepted and was sworn in as attorney general west on 24 May 1862, with Sicotte as his associate (he had been passed over lest the British authorities be enraged because he had caused the militia bill to fail).

Premier Sandfield Macdonald’s government was dominated by Baldwinites and Mauves, although it did contain Dorion and William McDougall*, and it was dedicated to the double majority. Difficulties were many: the province was torn by sectional and sectarian tensions, and a civil conflagration raging south of the border threatened Canada. At the same time Britain viewed the province with disdain and condescension. Sandfield secured approval of a measure that doubled the size of the provincial voluntary militia and provided for the encouragement of unpaid units. The defence budget was three times that of 1861 but less than one third that provided in Cartier’s bill. After it completed routine business Sandfield had the restless assembly prorogued in June 1862 and did not have it reassembled until 1863. In that interval he prepared legislation and pared expenditures.

He also tried to cope with the Duke of Newcastle, the irate colonial secretary, in order to improve Anglo-Canadian relations. Reasserting the argument that the defence of Canada was primarily a Canadian responsibility, Newcastle virtually demanded an active Canadian militia of 50,000 trained men. On 24 Sept. 1862, in Sandfield’s most important state paper, he and his cabinet informed Newcastle that Canada would support such a costly military force only during a state of war or imminent invasion. The province, it continued, had no quarrel with the United States; if war came, Canada would loyally respond, yet war would only come as the result of a British-American feud. Enlarging the militia would require direct taxation, which no Canadian government could sustain. The cabinet rejected Newcastle’s suggestion that army funds be placed beyond the control of the Canadian legislature as totally unacceptable to “a people inheriting the freedom guaranteed by British institutions.” It urged Britain to consider any Canadian expenditure on the construction of the Intercolonial Railway as expenditure for imperial defence. If he was unsuccessful with Newcastle, to whom the arguments were “buncombe,” Sandfield gradually brought Monck to an understanding of the realities of Canadian politics, and the two men developed a close and lasting friendship.

Sandfield met the assembly with optimism in early 1863: internal divisions seemed to have subsided, the administration was going well, and he could report that the volunteer force had reached 25,000 men. Nevertheless, the old disruptive issues remained unresolved, and they appeared in the crucial debate over Richard Scott*’s government-supported separate school bill. The issue of separate schools for the Roman Catholic minority of Upper Canada had bedevilled Canadian politics since at least 1850. The Scott bill, in its final emasculated form, seemed aimed mainly at clarifying the Étienne-Paschal Taché* act of 1856, which had been passed against a majority from Upper Canada, and it only slightly extended the privileges of the minority. Sandfield personally opposed the religious segregation of children but accepted the bill to achieve educational tranquillity, as did Egerton Ryerson*, the chief superintendent of education in Upper Canada. Scott and the representatives of the Irish hierarchy agreed that it would serve as the final settlement of their demands.

Both the Clear Grits and the Orangemen were in an uproar. Two events now changed the whole political situation: Dorion’s withdrawal from the cabinet because of his opposition to expenditures on the Intercolonial, and Brown’s reappearance in the assembly after winning a by-election. The Scott bill, backed by Sandfield, John A. Macdonald, Sicotte, Cartier, and Dorion, carried but without a majority from Upper Canada. Sandfield was furious with Brown and the Grits and he vainly argued that the passage of Scott’s bill did not really invalidate the double majority because his government retained the support of the two majorities. Sicotte’s hold on the erstwhile Bleu supporters, however, was faltering and there was a drift back to Cartier. The government was defeated in the assembly on 8 May even though it regained its majority in Upper Canada when Brown declared that he preferred John S. to John A. and Cartier.

Monck granted Sandfield a dissolution and Sandfield began secret negotiations with Brown, Dorion, Luther Holton, and Oliver Mowat* aimed at a reconstruction. He and others kept the double majority as their personal conviction but the government had to declare the basis of representation an open question. Sicotte was dropped for Dorion as Sandfield’s chief associate, and Sicotte, Michael Foley, D’Arcy McGee*, and other dropped ministers turned with a vengeance on their former chief. In the ensuing elections, “re-united” Reform swept Upper Canada but in the sweep Brown gained most. In Lower Canada the Mauves had already disintegrated, and although Dorion and his Rouges slightly improved their position, they could not win the majority. With a shaky lead of one, Sandfield could no longer govern in the image of La Fontaine and Baldwin.

Yet the régime survived through 1863 and made considerable progress. Plans for departmental and fiscal reforms matured. Sandfield secured the passage, with double majorities, of two defence bills which reorganized the militia, providing for service battalions, a volunteer force of 35,000, and a defence budget over twice that of 1862. Even the British press was impressed with these bills and with Finance Minister Holton’s restrained, though still unbalanced, budget. Brown himself seemed mellowed as he and Sandfield even entertained each other. The survey of the Intercolonial, but not the construction, was undertaken by Sandford Fleming* at Canadian expense; despite Dorion’s misgivings, alleviating somewhat Maritime distrust of Canadians, especially of Canadian Reformers. The government was also working on an unprecedented audit bill which would establish careful legislative scrutiny of departmental expenditures.

The old chronic deterioration then recommenced, and the tiny majority evaporated. Brown became hostile over cabinet changes, over Holton’s Montreal orientation in fiscal policies, and finally over Sandfield’s attempt to secure support from “loose fish” members in the Ottawa area. A vital by-election was lost. The assembly gathered in February 1864 with the opposition under Cartier eager and ready for the kill. It talked parliament to a standstill. Sandfield tried desperately to break loose from Brown by combining with Sir É.-P. Taché and other Bleus but failed and resigned on 22 March. The audit bill, his main legislative achievement, became law under his successor.

The régime which followed Sandfield’s fared even worse, falling within three months. Canada had reached a political impasse which reflected the centrifugal forces within the province; the political problem was not deadlock arising from two solid, equally matched phalanxes facing one another in the assembly but the impossibility of forming an executive in this multi-party situation where every government was a coalition.

Sandfield, with Monck’s backing, had attempted an unusual coalition with Taché that would consist of Reformers from Upper Canada and Bleus from Lower Canada. This was a precedent, but it failed, partly because it did not propose major constitutional change. In June, the “Great Coalition” involving Brown, Cartier, John A. Macdonald, and Alexander Tilloch Galt* was formed, dedicated to seek release from the impasse “by introducing the federal principle into Canada” and, if possible, by a linking of the Maritimes to the new system. Sandfield opposed federalism, which he considered a prodigal, divisive, and un-British system, one which would split “Central Canada” by cutting most of the upper St Lawrence off from its natural entrepôt in Montreal, but he did not necessarily disapprove of coalition or even British North American union. For the next three years he found himself on the side-lines leading a small disunited band of Upper Canadian Reformers, some of whom were Clear Grits, against union.

Sandfield expressed his viewpoint in the Canadian confederation debates in 1865. He was incensed by the haste with which a strange coalition, along with the British government and the Grand Trunk Railway, was demanding a major and indefinite constitutional rearrangement, even though the “disruption” of the union had not been an issue in the last election. The Canadian problem, he argued, was not really the present constitution but “demagogues and designing persons who sought to create strife between the sections.” The assembly did nevertheless approve the Quebec resolutions by a double majority, and Sandfield and Dorion later failed in their attempt to secure referral of the Quebec or subsequent London scheme to the people through a general election. The expectant Canadian Fathers would brook no notions of popular sovereignty.

Sandfield was a realist and soon accepted confederation itself as inevitable. During the latter part of the 1866 session he concerned himself mainly with trying to nudge the proposed constitution of Ontario toward his line of thought. He fully accepted supervision of provincial legislation but opposed, as a violation of responsible government, the prohibition against provincial tampering with separate schools.

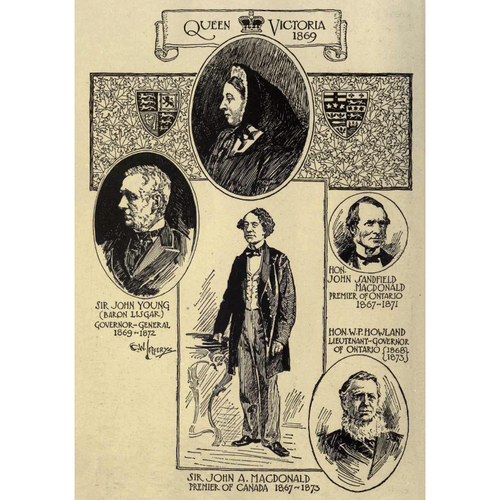

Where would he fit politically in the new scheme of things? Brown, his constructive work completed, had left the great coalition but John A. was determined to preserve it; without it, the Conservatives’ extremely weak position in Ontario might prove his political undoing in the new dominion parliament. With Brown and most of the Grits in opposition denouncing continuing coalition, the two Macdonalds were drawn toward one another and had serious talks in mid-1867. Given Monck’s enthusiastic approval, and counselled by John A. Macdonald’s chief confidant in Toronto, Senator David Macpherson*, the provisional lieutenant governor of Ontario, Sir Henry William Stisted, asked Sandfield Macdonald to become the first premier of Ontario. His coalition government was sworn in on 15 and 20 July 1867; besides the premier, who became attorney general, the cabinet contained another Baldwinite, a coalition Grit, and two Conservatives.

The “royal choice” had now to be submitted to the verdict of the electorate. In Ontario this was a unique election: voting for federal and provincial candidates took place at the same time and the two first ministers, the two Macdonalds, “hunted in pairs,” crossing and recrossing the province trying to work out compromises and deals so that Coalition Reformers and Conservatives would face only “factious” Grits. When the count for the Ontario legislature was in, it was clear that about 50 of 82 members, with more Conservatives than Reformers, were prepared to follow the “Patent Combination” led by the gaunt and sickly lawyer from Cornwall, himself elected to both parliaments.

With a great martial display, Sandfield had Ontario’s first legislature opened on 27 Dec. 1867. The ensuing session went well and its greatest achievement was undoubtedly Stephen Richards’ homestead act. It was modelled on the American act of 1862 and provided for virtually free land for homesteaders on surveyed crown lands of Muskoka, Haliburton, and north Hastings. Another act encouraged the northern extension of railways into these “free land grant” areas, and during the next three years this policy of northern development was broadened, further liberalized, and extended to include growing concern for forestry and mining developments as well as for settlement.

Sandfield showed his predilection for the separation of church and state and for retrenchment by concentrating aid on the University of Toronto and cutting off the rather feeble denominational colleges, over Ryerson’s and Sir John’s objections, but with opposition approval. Sandfield later regained Ryerson’s confidence by supporting his plan to reorganize the primary and secondary school systems: free schooling, compulsory attandance, standard teaching qualifications, more emphasis on science in the curriculum, and municipal financial support for both levels were all part of this proposal. The Liberal opposition, led by Edward Blake*, fought the bill, especially its compulsory and centralizing features, so vehemently that it was not passed until 1871. The same year enabling legislation was passed for the Ontario School of Agriculture, opened in 1874 (later the Ontario Agricultural College, now the University of Guelph), and a technical college (ultimately the Ryerson Polytechnical Institute).

Sandfield’s other important legislation was the election act of 1868, which established “same day” elections throughout Ontario and considerably broadened the franchise, and in the field of social welfare institutions. His prison and asylum inspection act of 1868 and other subsequent measures gave his fighting inspector J. W. Langmuir* vastly increased powers to begin the long overdue task of prison and hospital inspection and reform. Large additions were begun on the Toronto Asylum for the Insane and an asylum was established in London. He also had constructed the Ontario Institution for the Deaf and Dumb in Belleville and the Ontario Institution for the Blind in Brantford.

Solid and substantial as these reforms were, they failed to capture the Ontario mind. Instead, Grit accusations that Sandfield was a kept man, vassal of the Canadian prime minister, gained more and more credence. There was little substance to the charge; surviving correspondence clearly shows this. Sir John’s chief complaint was that Sandfield was too independent for his own good and for the proper operation of the new and, as Sir John vainly hoped, highly centralized system. In fact, Sandfield, like Sir John, really preferred United Kingdom-style legislative union but accepted the quasi-federalism of the British North America Act, which clearly seemed to provide for provincial subordination to the central government in Ottawa. Admitting this system, Sandfield was as much his own master as he dared, and he chafed when Sir John declined to consult him about senior Ontario appointments.

Despite disagreements, Sandfield and Sir John again “hunted in pairs” in 1868 and went to Nova Scotia to persuade Joseph Howe to accept confederation. Then, in the summer of 1869, the prime minister infuriated Sandfield by appointing his old enemy, Sir Francis Hincks, lately returned to Canada, as minister of finance and McDougall’s replacement as Reform leader in the cabinet. To Sandfield, the old railway broker was neither a Reformer nor an honest man. Late in 1869 and early in 1870, Sandfield was involved in various schemes aimed at overthrowing Sir John and creating some new kind of combination, perhaps under himself or Cartier. At one point he even had discussions with Brown. Nothing came of these plots, and the Grits prepared instead to destroy Sandfield. They were assisted by the revival of anti-French feelings accompanying Louis Riel*’s adventures on the Red River, when Sandfield’s identification with Sir John caused him to be included in accusations made against the latter.

Sandfield was vulnerable from the candid and rather crude way in which he used the patronage system, a system which he, like Baldwin, believed to be an essential aspect of responsible government. He did not regard the Ontario legislature as a sovereign parliament, moreover, and emphasized the role of the provincial cabinet. Though noted and abused for his personal parsimony, he had the legislature vote large, only vaguely appropriated amounts of money for governmental expenditure. When, in 1871, $1,500,000 from the huge provincial surplus was voted for purposes of aiding the northern extension of railways, the Grits had a popular issue although it has never been shown that any of the money was improperly expended.

The results of the spring election of 1871 were inconclusive. The Grits made the campaign for the defence of Ontario rights almost a holy crusade. Sandfield’s efforts were seriously curtailed by his rapidly declining health. He had been suffering repeatedly from long “infernal colds” and had to spend most of the campaign in bed with rheumatic pains and high fever. Equally serious, Sir John, in Washington for the protracted negotiations which would lead to the Anglo-American treaty, was unable to pull the usual strings. But although the Grits swept most of the western peninsula with the exception of London they did not have a clear majority; a very ill Sandfield determined to carry on and meet the legislature even if he had “to be carried there in a blanket.”

One of his own reforms proved his undoing. The Grits charged irregularities in the election of six Sandfield men but were themselves only charged for one. The Controverted Elections Act of 1871 took decisions on electoral irregularities out of partisan committees of the legislature to the courts; it also provided, unwisely, that while the matter was before the courts, the member whose election was being investigated could not take his seat. Under the stern provisions of the law, by-elections had also to be called, but they could only be called after parliament opened, which it finally did on 7 Dec. 1871.

With so many vacancies, Sandfield claimed that a non-confidence vote could not overthrow his government but Blake moved the motion nonetheless. He chose the issue of the railway appropriation, an astonishing motion because it really attacked the former legislature, not the cabinet. It carried by seven votes. Sandfield refused to resign, but the one Grit coalitionist in the cabinet, Edmund Burke Wood*, joined forces with Blake. The assembly was paralysed and the speaker, R. W. Scott, whom Sandfield had appointed in an attempt at mollification after the Sandfield Macdonald family had repeatedly clashed with him on social, economic, and political issues, appeared to act in support of Blake’s position. All efforts at a compromise failed. Sandfield’s support ebbed away and efforts to adjourn failed. On 19 February he announced the resignation of his government and Blake became premier in a cabinet which included Scott. Despite its fall from power, Sandfield’s coalition, ironically, won all but one of the by-elections called.

Although Sandfield occasionally reappeared in the assembly, his health prevented him from acting as leader of the opposition, and this role was taken up by Matthew Crooks Cameron*. He also gave up law, which he had practised in partnership with John and Donald Ban MacLennan. He had concentrated on real estate law, and it had made him a wealthy man. He was, however, able to play the key role in securing the services of Thomas Charles Patteson as editor of a new broadly financed daily, the Toronto Mail, to challenge the Globe and act as the Ontario spokesman for both the Ontario opposition and Sir John A.’s government.

Confined to bed in March 1872, Sandfield blithely wrote Patteson that he secretly believed that he had “a touch of the horse distemper.” But in May doctors informed him that his heart was so “displaced and impaired” from previous illness that death was imminent; he took the news bravely and philosophically. On 1 June he died at Ivy Hall.

Throughout his career, John Sandfield Macdonald was enigmatic, and there is still no agreement among historians as to his stature. Usually a light-hearted and an affable man, he and his wife were famous for their gala entertaining. He could, however, when slighted or attacked, be vindictive and sustain a grudge. Although not a truly great man he did give Ontario four good years of service, efficiently establish the machinery of provincial government, and carefully and creatively begin the long process of reform and construction which the paralysis of pre-confederation politics had so long delayed. But Ontario was not really his focus; instead it was the old “central Canada,” based on Montreal and expressed in the “bicultural” Province of Canada.

As premier of Canada, Sandfield had lowered the temperature of sectional, sectarian, and cultural conflict, though the specific constitutional details of his double majority were hardly realizable; he thus made the Great Coalition and confederation more attainable. His central concept of Canada as a land of two majorities has again now found increasing acceptance. Sandfield’s opposition to the details of the Quebec scheme and to the procedures for implementing it might show some lack of realism or foresight but hardly, as has been claimed, a lack of vision. It was not union but the American kind of federalism which he opposed. On the other hand, as premier, he accepted the system established by John A. Macdonald and can therefore scarcely be accused of betraying Ontario because he did not endorse the new doctrine of provincial rights and coordinate federalism that the Grits were now successfully advancing.

As a political leader he was not able, as did George Brown or Sir John A. Macdonald, to secure a large body of geographically dispersed followers dedicated to him personally. He was essentially a central Canadian based in Cornwall, looking as much to Montreal as to Toronto, not the best of places from which to lead Upper Canadian Reform.

[A complete list of the sources, primary and secondary, used in the preparation of this biography for the period up to March 1864 in given in the author’s “The political career of John Sandfield Macdonald to the fall of his administration in March 1864: a study in Canadian politics,” unpublished phd thesis, Duke University, 1964. A selective bibliography appears in the author’s John Sandfield Macdonald, 1812–1872 (Toronto, 1970). b.w.h.]

MTCL, Baldwin papers. PAC, MG 24, B30 (Macdonald-Langlois papers); B40 (Brown papers); MG 26, A (Macdonald papers); MG 27, II, D14 (Scott papers). Queen’s University Archives, Alexander Mackenzie papers. Canada, Province of, Confederation debates; Legislative Assembly, Journals. Ontario, Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1867–72. Globe (Toronto), 1844–72. Leader (Toronto), 1852–72. London Free Press, 1849–64. Mail (Toronto), 1872. Quebec Daily Mercury, 1862–64. “A letter on the Reform party, 1860: Sandfield Macdonald and the London Free Press,” ed. B. W. Hodgins and E. H. Jonse, Ont. Hist., LVII (1965), 39–45. Careless, Brown. Chapais, Histoire du Canada, VI–VIII. Cornell, Alignment of political groups. Dent, Last forty years. B. W. Hodgins, “Attitudes toward democracy during the pre-confederation decade,” unpublished ma thesis, Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.), 1955. Morton, Critical years. Waite, Life and times of confederation. B. W. Hodgins, “Democracy and the Ontario fathers of confederation,” Profiles of a province: studies in the history of Ontario (Ont. Hist. Soc. pub., Toronto, 1967), 83–91; “John Sandfield Macdonald and the crisis of 1863,” CHA Report, 1965, 30–45.

Cite This Article

Bruce W. Hodgins, “MACDONALD, JOHN SANDFIELD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_john_sandfield_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_john_sandfield_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Bruce W. Hodgins |

| Title of Article: | MACDONALD, JOHN SANDFIELD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |