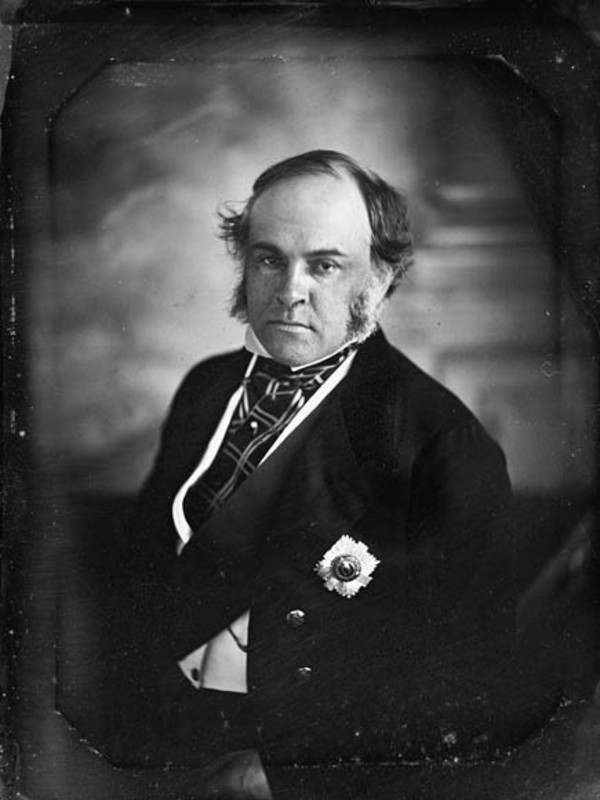

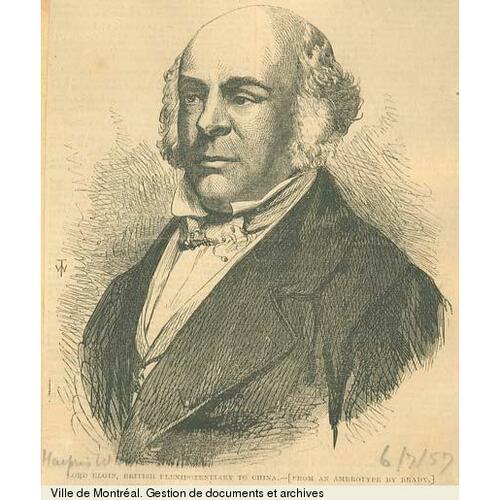

BRUCE, JAMES, 8th Earl of ELGIN and 12th Earl of KINCARDINE, colonial administrator; b. 20 July 1811 in London, England, second son of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin and 11th Earl of Kincardine, the “saviour” of the “Elgin Marbles,” and of Elizabeth Oswald; d. 20 Nov. 1863 at Dharmsala, India.

James Bruce, as a younger son until 1840, had to fit himself for work, and the career he actually followed owed much of its success to his education and to his early preparation for an occupation. He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, and became one of a brilliant group of Eton and Christ Church graduates, many of whom were later associated in politics and the colonial service.

Bruce studied intensively, so much so that he injured his health and had to forego a double first for a mere first. Nevertheless he left Oxford not only widely read in classics but having “mastered” on his own, so his brother recorded, the philosophy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The latter, with its stress on the organic nature of society in which the members and interests are dependent on one another, was a suggestive and intriguing acquisition for a young man who was to lead, with the ready address and genial charm already apparent at Oxford, fragmented and unformed societies towards a new coherence in self-government.

On graduating in 1832, Elgin returned to Scotland to assist in the management of the family estates, and to read and think. But he had a political career in view. In 1834 he addressed a Letter to the electors of Great Britain, in which he showed himself a liberal-conservative of the model of Sir Robert Peel, and of the cast of thought derived from the philosophy of Coleridge. He failed to win election in the county of Fife in 1837 because of entering late, but in 1840 was returned for Southampton. He seconded the amendment to the address which brought down Lord Melbourne’s government in 1841. But already in 1840 he had become on the death of his elder brother the heir to the earldom, and on his father’s death in 1841 had to give up, as a Scottish peer, hopes of advancement as a member of the House of Commons.

In 1842, however, he accepted appointment as governor of Jamaica, and went there with his new wife, Elizabeth Mary Cumming-Bruce. Unhappily for the health of the latter, who was pregnant, the party suffered shipwreck on the way. In Jamaica Elgin found a society divided by racial differences and suffering the effects of an economic depression brought on by the abolition of slavery in 1833, circumstances not unlike those he was to find later in Canada. He also found a classic model of the old colonial constitution from which Canadian Reformers were seeking to escape. Jamaica was thus in many ways a preparation for Canada. It also gave Elgin an opportunity to use his personal charm and public diplomacy in turning men’s thoughts to practical improvements and moderate politics.

In 1846, saddened by the loss of his wife and concerned for his own health and that of his daughter, Elgin returned on leave to England. The new colonial secretary in Lord John Russell’s Whig administration, Lord Grey, was impressed with Elgin’s performance in Jamaica and urged him, without success, to continue there. Grey then invited Elgin to assume the governorship of Canada. The acceptance of a Whig appointment by Elgin, and the appointment of a Tory by Grey, forecast the non-partisan role which Elgin was to play in his new post. By coincidence, this new political character was underlined by his marriage to Lady Mary Louisa Lambton, daughter of Lord Durham [Lambton*] and niece of Lord Grey. He was thus, publicly and privately, splendidly fitted to carry out the mission Grey had given him, to elaborate and confirm the practice of responsible government in the British North American provinces. Grey had made the idea explicit by his analysis of the conditions which stood in the way of responsible government in Nova Scotia in his important dispatches of 3 Nov. 1846 and 31 March 1847. Elgin’s conduct in Canada defined through practice the form of responsible government and he was to expand it into a major anticipation of the Canadian nationhood which was yet in embryo. His private correspondence with Grey was in fact an agenda of what was to be done in British North America during the next generation.

Elgin reached Canada on 30 Jan. 1847, and at once met the incumbent Conservative government. It had been elected in 1844 following the resignation of the Robert Baldwin*–Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine government and, although committed to support the governor and to resist the application of responsible government, it had itself under the leadership of William Henry Draper* become in effect a party government. There was some anticipation that Elgin as a Tory would assume direction of the government, but others thought that, as a governor sent by a Whig administration to recognize responsible government, he would dismiss the Draper ministry and call the Reformers to office. Elgin did neither. He had determined before his arrival not to be “a partisan governor,” as his predecessor Sir Charles Metcalfe* had seemed to be. He would assume “a position of neutrality as regards mere Party contests.” This was the first step in confirming in Canada what he felt certain it was his mission to ensure, what he termed “constitutional Government.” By that he meant government by the full body of conventions controlling the formation and functioning of the cabinet and the role of governor general as the representative of the crown. In short, it was the parliamentary monarchical government then being confirmed by use in the United Kingdom.

Elgin accordingly made it clear that he would support Draper either in a new session of the legislature, or in his endeavours to strengthen his position in parliament by seeking support from the French followers of La Fontaine. Elgin himself wrote to Augustin-Norbert Morin to suggest French support for the ministry, the more readily as he accepted Draper’s opinion that the existing division of parties, with the Tories looked upon as the “English” party and the Reformers the “French” party, was no more than transitory. But Morin and his associates, whom Elgin considered essentially conservative, declined Elgin’s proposal and the alliance did not occur at that time.

Having failed in its bid for French support, the government requested dissolution late in 1847, and the Reform party won a decisive victory in the ensuing election. The ministry, defeated in parliament, resigned as a body. The practice since 1841 had been simply to reshape ministries with some former members in the new, but when Elgin invited La Fontaine to form a ministry, he did so as leader of a party. Elgin, as a neutral governor, thus accepted the first administration deliberately based on party in Canadian history. In placing the crown which he represented above party politics, and in leaving the power to govern in the hands of a ministry of the leaders of a defined and organized party, Elgin revealed what he meant by constitutional government. The party character of the ministry meant also that the cabinet was collectively responsible through the prime minister for policy and administration. The governor would no longer be head of the government responsible for its acts in all matters of local administration and legislation. Nor would he have a voice in matters of local patronage as Metcalfe had wished to have, but to prevent the establishment of a Jacksonian spoils system he had to ensure that major and permanent civil servants, being politically neutral, should have security of tenure.

Elgin had, of course, duties as an imperial officer, specific instructions from the colonial secretary, some voice in decisions concerning defence and foreign relations, as well as control of Indian affairs and other as yet untransferred imperial responsibilities; these precluded his playing an altogether neutral role. And both he and Grey had to act judiciously and tactfully in re-modelling the simple and archaic governmental procedures of Canada to deal with the complex administrative and conventional practices of British cabinet government. Elgin was thus, in confidential fashion, a far more active governor than his new definition of the office implied. Fortunately, La Fontaine, Baldwin, and Francis Hincks* desired the same ends as he did, and trusted him, so that the process of creating full parliamentary government went forward smoothly. Not that it was a mere matter of office organization; party control of patronage meant of course that hundreds of public offices went to French Canadians, others to English Reformers, both of which groups had had scant access to public employment before. Elgin put the finish to his new version of his office by traditional ceremony and entertainment, and also by less formal visits, official ceremonies, and public speeches. His personal charm aided greatly in all this, as did his personal simplicity.

The new Reform ministry, which was sworn in on 11 March 1848, marked the coming to power of French Canadians as members of a party, not as individuals, and represented as well the outcome of the long agitation for colonial self-government. It soon had to face, with Elgin’s guidance and advice, the consequences of economic and external changes in the critical years from 1846 to 1850.

The first was the repeal in 1846 of the Corn Laws; it had precipitated the collapse of the old colonial system, and had impelled Russell and Grey to base their policy in British North America on the recognition of full responsible government in local matters. Another problem was the famine migration from Ireland to Canada and the United States in 1847. Not only did it bring to Canada some 70,000 Irish immigrants in that year, many of whom were to create burdens because of the ravages of cholera, but it also made real the possibility of Irish Americans striking at Great Britain through British North America. Elgin had to keep watch on Irish organizations and meetings in Montreal and on the Irish agitators of Boston and New York. Discontent in Ireland might too easily blend with discontent in Canada.

To these concerns was added in 1847 the financial and commercial depression which followed the collapse of the railway boom in the United Kingdom. Coming upon the repeal of the Corn Laws and the loss of guaranteed British markets for Canadian goods, commerce in Canada was completely disrupted. The falling off of trade, the increase of bankruptcies, and the collapse of investment values may well have been caused by the depression alone, but it was natural for Canadian businessmen to attribute them to the ending of the familiar protective system.

The Canadian constitutional revolution of 1848 may have forestalled an echo in Canada of the European liberal revolutions of that year begun in France. That there was apprehension is corroborated by the reaction to the return of Louis-Joseph Papineau* from exile in Paris. He came out eloquently and strongly as the critic of the “sham” of responsible government, and set out to become again the leader of French national feeling. The popularity he acquired almost immediately caused some fear among the French Canadian supporters of the Reform party. But the French ministers, aided by Elgin, set out to undermine his popularity and reduce him to an isolated figure mouthing the battle cries of an age of perpetual opposition. They remorselessly and cruelly succeeded in damping down the embers of revolution in Canada, although dissension continued in the activities of the republican and annexationist Rouges, the heirs of Papineau.

It was fortunate, in view of the next stage of the Canadian crisis, that Papineau had probably been reduced to impotence by the end of 1848. For, even if Papineau were powerless, there was a measure, required by both justice and policy, which was to demonstrate clearly to French Canadians that responsible government was not a sham but a reality. The indemnification of those who had suffered damage by acts of the troops and government in suppressing the rebellion of 1837 in Lower Canada (it had been done for Upper Canada) had been taken up by Draper’s ministry, and a royal commission had recommended payment for losses incurred by those not actually convicted of rebellious acts. The Draper ministry took no action, but clearly an administration headed by a French Canadian and supported by the French Canadian members of the assembly and under attack by Papineau, had, in policy as well as justice, to take it up. The Rebellion Losses Bill was passed by majorities of both Lower and Upper Canadian members despite the Tory opposition’s cry that it was a bill to pay “rebels.”

Fully to understand Elgin’s dilemma in dealing with the bill, it is necessary to realize that the Tory opposition, as well as the government, were testing responsible government and learning the new rules, and that Elgin was their mentor little less than he was that of his ministers. For the most part they, and especially their leader Sir Allan Napier MacNab, were simply old-fashioned Tories, not sure that the new regime might not lead to a continuation of earlier conditions when ministries acquired permanency, only this time it would be a Reform ministry with French Canadian support. MacNab’s remarks early in the debates on the bill are suggestive: “We must make a disturbance now or else we shall never get in.” He knew also that the governor general, as an imperial officer, might properly decline to sanction the “paying of rebels,” and that he could in any case dissolve the parliament or reserve the bill for the decision of the imperial government. MacNab was thus trying to force Elgin into using the powers left him under responsible government.

Elgin refused to be turned away from the role he had assumed. His ministry had an unshaken majority; there was no indication that an election would alter that fact and much that it would provoke racial strife in Lower Canada. The matter was also local, not imperial; it was therefore to be dealt with locally by the governor’s assent; if his superiors disagreed, they could recall him. If he reserved the bill, it would simply embroil the imperial government in local Canadian affairs and perhaps provoke another Papineau rising with American and Irish aid. So he drove down to the parliament house on 25 April 1849, and gave his assent to the bill.

The immediate result was a violent attack by a mob of “respectable” demonstrators on the governor’s carriage as he drove away. The next was the deliberate burning of the parliament buildings by the same mob, followed by rioting in the streets and attacks on the houses of La Fontaine and Hincks. Montreal was at the mercy of an organized and aggressive Tory and Orange mob, which conservative citizens either actively joined or refrained from resisting. When Elgin returned to meet parliament on 30 May to receive an address, his carriage was again assaulted with missiles and he carried off a two-pound stone thrown into it. The home of La Fontaine was again attacked, and one man killed by its defenders. Elgin remained outside the city for the rest of the summer in order not to provoke yet another outburst, with the possibility of racial violence. This course, although criticized by some as cowardice, showed great moral courage and was an important measure of his powers of restraint. His ministers could not be quite as quiescent. Government went on, but the troops were called in and the police were increased. Their policy, modelled on Elgin’s conduct, was, however, not to answer defiance with defiance, but to have moderate conduct shame arrogant violence. In the end the policy succeeded, but only at the cost of suffering the climax of Tory Montreal’s frantic despair. In October 1849, after frequent indications of what was to come, there appeared the Annexation Manifesto which advocated the political and economic union of Canada and the United States and was signed by scores of persons of political and commercial significance. It was an act of desperation, the act of men whose world had been turned upside down, the empire of protection and preference ended, the empire of the St Lawrence centred on Montreal disrupted, British “ascendancy” replaced by “French domination.”

MacNab’s role in the outcry and riots against the Rebellion Losses Act had failed to coerce Elgin or to force his recall; at bottom the Annexation Manifesto was a reply to Elgin’s firmness. If the queen’s representative was to welcome French Canadians to power in equality with the English and to convert the commercial system of the old empire into a new system of local government, free trade, and sentiment based on common institutions and common allegiance, the embittered loyalists and financially embarrassed businessmen of Montreal thought annexation an alternative so just it would be given for the asking. To men thinking in the old terms Elgin could seem only a traitor or a trifler. Elgin was neither. He foresaw a nation of diverse elements founded on the temperate exercise of tested institutions and conventions. So did Grey and the Russell government, which showed its approval by advancing Elgin to the British peerage with a seat in the House of Lords. So did his ministers. The men who had signed the manifesto while holding commissions from the crown, as many Tories did, were required to abjure the manifesto or forfeit their commissions. Montreal, which had attempted to coerce the parliament and government of all Canada, was declared unfit to be the seat of government.

These measures stemmed the violence of the outraged Montrealers. Moreover, the general current of events turned the attention of businessmen everywhere to more congenial pursuits. By 1850 prosperity was returning to Montreal and Canada. In prosperity even responsible government and “French domination” could be tolerated. MacNab called on Elgin and was politely received. Responsible government and all it implied – French Canadians in office, British, not American, conventions of government, efficiency in public finance and the civil service, local decision-making and local control of patronage – had been tested in the fires of riot and the threat of annexation.

Much remained to be done, and Elgin’s further four years in Canada called for the exercise of the same talents as did the turbulent year 1849. There were local reforms to be carried out, such as the abolition of the clergy reserves and of seigneurial tenure in Lower Canada. The latter was a clearly local issue and was dealt with by the Canadian parliament. But the clergy reserves, governed by an imperial act of 1840, could not be touched without an act of parliament of the United Kingdom enabling the Canadian legislature to deal with them. The question invited the same appeal to Britain as the Rebellion Losses Act had done, especially as nothing could more symbolize an empire and a nation across the seas than a common established church. Elgin recommended that the imperial parliament be asked to end the act of 1840 and leave the future of the reserves to the Canadian parliament. After repeated efforts were foiled by opposition of the bishops in the House of Lords, this action was taken and in 1854 the reserves were ended, but on terms respecting vested interests. In the same year seigneurial tenure was abolished.

That this legislation was the work of a Liberal-Conservative Anglo-French party in coalition pleased Elgin, as such a union was the outcome of the regime of local decisions by moderate and responsible men which he had made possible in Canada. But more exhilarating, no doubt, was the long delayed conclusion of the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States, the final act of Elgin’s personal diplomacy. Foreseen as early as 1846 in Canada as a necessary outcome of the dismantling of the protective system, reciprocity had been repeatedly defeated in the United States for lack of evident advantage to American economic interests and because of its implications as a possible prelude to annexation, a step which would upset the balance of free and slave soil in the expanded republic of 1848. The inducements of free navigation on the Canadian section of the St Lawrence and of access to the fisheries of the Atlantic provinces removed American objections that it conferred no benefits on the United States. In 1854 the British government acknowledged the need to lobby Congress. Elgin went to Washington and in a diplomatic tour de force persuaded the Southern senators that reciprocity would prevent, not provoke, annexation. It was a brilliant climax to seven years of intense persuasion, in which he had established the conventions of constitutional, monarchical, and parliamentary government in Canada, and ensured that prosperity without which he believed, as had Durham, Canadians could not be expected to prefer self-government in the empire to annexation to the United States.

Elgin returned to Britain in December 1854. Despite approaches, he remained outside active politics there. In 1857 the dispute with the empire of China over the lorcha Arrow and British trading rights in Canton led to his commission by the Palmerston government as a special envoy to China. The mission was delayed by the need to assist in the suppression of the Indian Mutiny. In 1857, however, in consort with a French envoy, Elgin made his way by armed force into Canton, and in 1858 negotiated at Tientsin with representatives of the imperial government a treaty providing for a British minister to China, additional trading rights, protection of missionaries, and an indemnity. He then went to Japan where he concluded a commercial treaty. He returned to England in 1859 and accepted, as did other former Peelites, office in the new Palmerston government. He became postmaster general, not the best use of his talents which were diplomatic rather than administrative. However, in 1860, as a result of the Chinese government’s refusal to implement the Treaty of Tientsin, Elgin was again sent with an Anglo-French military force and a French colleague to ensure the acceptance of the treaty. The army advanced to Peking and, after the murder of some English captives, the Summer Palace of the emperors was burned on Elgin’s decision to avenge the insult and to enforce the signature of the treaty.

In 1861 he was appointed viceroy and governor general of India, but over-exertion on an official tour in 1862 brought a fatal heart attack the next year. There is no evident connection between Elgin’s service in Jamaica and Canada and that in the Far East and India. The same decisiveness and diplomatic skill are apparent. But it is perhaps the unusual degree to which he sympathized with the Chinese he encountered and perceived the difficulties of a decadent empire that was most remarkable. He set out to understand India also, not by study of the conventions of the British regime, but in travelling among the people. It was the same desire and capacity to understand the society in which he was to govern that had enabled him to assist in creating in Canada a locally acceptable government of moderates between the extremes of race, partisanship, and tradition. What was extraordinary in Elgin’s career in Canada was his immediate and imaginative mastery of his role, and the creative spirit in which he developed it.

Elgin-Grey papers (Doughty). Letters and journals of James, eighth Earl of Elgin, ed. Theodore Walrond (London, 1872). R. S. Longley, Sir Francis Hincks; a study of Canadian politics, railways, and finance in the nineteenth century (Toronto, 1943). D. C. Masters, The reciprocity treaty of 1854: its history, its relation to British colonial and foreign policy and to the development of Canadian fiscal autonomy (London and Toronto, 1936). Monet, Last cannon shot. J. L. Morison, British supremacy & Canadian self-government, 1839–1854 (Glasgow, 1919); The eighth Earl of Elgin . . . ([London], 1928). G. N. Tucker, The Canadian commercial revolution, 1845–1851 (New Haven, Conn., 1936).

Cite This Article

W. L. Morton, “BRUCE, JAMES, 8th Earl of ELGIN and 12th Earl of KINCARDINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bruce_james_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bruce_james_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. L. Morton |

| Title of Article: | BRUCE, JAMES, 8th Earl of ELGIN and 12th Earl of KINCARDINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2025 |