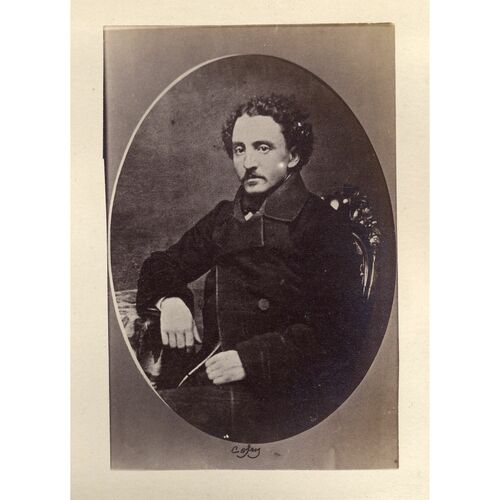

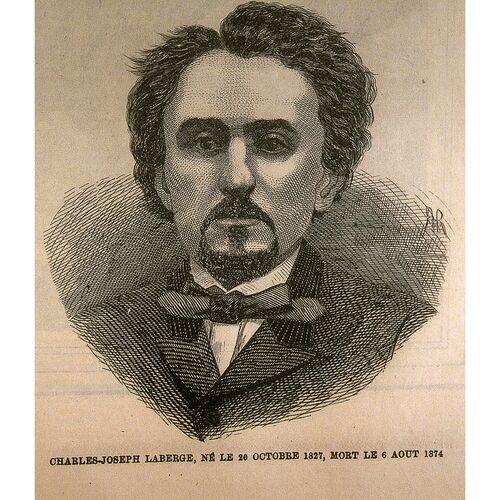

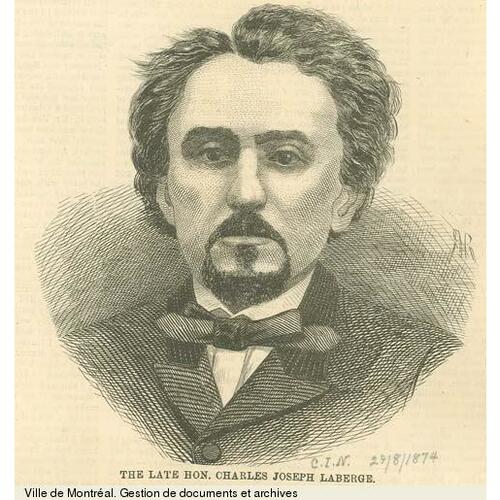

LABERGE, CHARLES, lawyer, journalist, politician; b. 21 Oct. 1827 at Montreal, L.C., son of Ambroise Laberge, a merchant, and Rose Franchère, sister of the explorer Gabriel Franchère*; d. 3 Aug. 1874 at Montreal, Que.

Charles Laberge’s mother, who early became a widow and had only limited means, gave music lessons for some time, in order to meet the needs of four children of tender years. Charles, whose health gave her cause for anxiety, was committed to the care of a farmer at Rivière-des-Prairies, so that the pure country air would strengthen his lungs.

He enrolled at the college of Saint-Hyacinthe in 1838 and completed his classical studies in 1845. All the evidence indicates that young Laberge at once impressed his masters and fellow-students by his intellectual liveliness and an aptitude for assimilating knowledge which won him, as Laurent-Olivier David* wrote, “effortlessly and without work successes that many others labour after in vain.”

In the literary and oratorical assignments particularly his gifts showed themselves with the greatest felicity. A journalist in embryo, he founded at the college a journal with the predestined title Le Libéral, in which his waggish pen ran freely at the expense of teachers who displeased the pupils. While speaking one day before Lord Elgin [Bruce*], who was visiting the college, he earned the compliment that he would become a distinguished orator, a forecast which Louis-Joseph Papineau, after his return from exile, said was already realized when he heard him during the literary exercises in 1845. “Frankly, M. Laberge, I have never spoken as well as you have just done; if I have had the title of Speaker, you have the speaker’s talent.”

At the end of his college years, Charles Laberge studied law at Montreal under René-Auguste-Richard Hubert. He was called to the bar in 1848 and went into partnership with the lawyer Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme*, but in 1852 he moved to Saint-Jean-d’Iberville, where in a short time he acquired a large clientele.

While still a law student, Laberge had been intensely active in the Institut Canadien, of which he was a founder. In November 1845 his confrères had elected him corresponding secretary of their association. When L’Avenir began to appear in November 1847 he was one of “thirteen” contributors whose average age was not more than 23. Both on the rostrum of the Institut Canadien and as a journalist, he tackled the most varied subjects, but he insisted above all that it was necessary for Canada to be annexed to the United States. In a series of articles that appeared in L’Avenir from 2 June to 30 Oct. 1849, signed “34 stars,” he developed the following thesis: “We have reached the time when Canada must become a republic, when our star must go to take its place in the American sky.” With Jean-Baptiste-Éric Dorion*, Joseph Papin*, and Charles Daoust*, some of his friends from the Institut Canadien and L’Avenir, he allowed himself to be carried into active politics in the wake of Louis-Joseph Papineau. In 1854 he was elected member for Iberville County; with 10 of his confrères of the Institut Canadien who had also been returned by their respective counties, he belonged to the constellation of young Liberals, headed by Antoine-Aimé Dorion*, whom two political adversaries, Joseph-Charles Taché* and Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau* under the pseudonym Gaspard Le Mage, endeavoured to ridicule in a pamphlet called La pléiade rouge.

In the house, according to Oscar Dunn*, Laberge “was on his own ground, in the element most suited to his abilities. Not sufficiently wily to be a first rate lawyer, or sufficiently profound to dominate on the bench, he possessed a natural gift of eloquence, a breadth of ideas, an uprightness of character which won him, without effort on his part, an exceptional place in a deliberative assembly.” And Dunn added: “He had a fine turn of speech, a French of true quality; in this respect no one in our country was more gifted than he.”

When the Conservative ministry fell in 1858, over the question of the seat of government, Laberge agreed to become solicitor general in the cabinet of George Brown and Antoine-Aimé Dorion, which lasted only two days. Although ephemeral, this alliance with the Scotsman whom French Canada hated was certainly not calculated to increase his stature in his own eyes and in those of his friends.

Be that as it may, in 1860 he decided to leave active politics and devote himself exclusively to his family and his profession. Hence he refused to stand as a candidate in the 1861 general elections. He did allow himself to be appointed a judge at Sorel in 1863 by the Liberal government, but the Conservatives, back in power the following year, lost no time in getting him to return to private life. He accepted this situation philosophically, being thoroughly happy in the home that he had set up on 23 Nov. 1859, when he married Hélène-Olive Turgeon, daughter of the former legislative councillor, Joseph-Ovide Turgeon.

Journalism always had a keen attraction for him. In 1860, with his friend Félix-Gabriel Marchand*, he established Le Franco-Canadien (Saint-Jean-d’Iberville), to which he contributed from time to time. He did the same for. another liberal paper, L’Ordre (Montreal), in which he published articles signed “Liberal but Catholic.”

Like the majority of his liberal friends, he took a stand against the projected confederation of the provinces of British North America. In 1865, replying in a public meeting at Montreal to those who said that the opponents of confederation offered no other remedy, he exclaimed: “I do not admit that a change of constitution has become necessary, but supposing it has, can we justifiably accept a political régime which will give us three or four enemies instead of one? If we already have so much difficulty in struggling against Upper Canada, what shall we do when we have to fight three or four other provinces?” He proposed the “separatist” solution: “If the constitution must be changed, let us separate since we cannot agree, and let us have the questions of customs and tariff that concern all the provinces settled by a small congress which will not have the right to deal with anything else.”

It was no doubt at the repeated requests of his liberal friends that in 1872 he tore himself away from his little town of Saint-Jean-d’Iberville, where he was keenly appreciated by his fellow-citizens who had twice elected him mayor, to go back to live in Montreal and take on the editorship of Le National. In its first number, on 24 April 1872, this paper broke with the tradition of L’Avenir and Le Pays: “Le National will be a political and not a religious journal, but the special organ of a Catholic population, and, in conformity with the beliefs of those directing the journal, we shall when occasion arises adopt entirely the Catholic viewpoint; we disavow in advance anything which in the rapid compiling of a daily newspaper might slip through by inadvertence, and expressly declare our entire devotion and our filial obedience to the Church.” Laberge, his health already seriously affected, was unable to show what he was capable of. His friend Oscar Dunn says that “it was only by dint of truly heroic efforts that he managed to write his articles, while in the grip of the disease that was eating him away.” “Poor and burdened with a family, he silenced his tortures in order to accomplish his daily task; and his sense of duty was so developed that he drew from it the strength to master his sickness, so much so that sometimes he deceived his family and gave it fleeting periods of hope.”

To physical suffering was added moral suffering. A firm Christian, he had always been distressed by the suspicions of some opponents and even some members of the clergy about his religious beliefs, because he professed himself a liberal. This suffering had been sharpened when the Institut Canadien, after being the object of episcopal censures in three pastoral letters issued by Bishop Ignace Bourget* on 10 March, 30 April, and 31 May 1858, lost some 135 of its members, who broke away to found the Institut Canadien-Français [see Cassidy]. When in 1867 conservative papers started to revile the members of the Institut Canadien by styling them “excommunicates,” Charles Laberge was roused, and in a letter from Saint-Jean dated 16 Aug. 1867 he informed Bishop Bourget that as one of “the founders” of the institute, and because he was “still a member” although he no longer took part in its meetings, he wished to be enlightened in the “cruel embarrassment” in which he found himself with regard to “the positive assertion of excommunication” directed against him and his confrères.

According to him, the differences of opinion that had resulted in the unfortunate scission of 1858 could have been avoided: “When, some years back, difficulties arose, I thought, and I still think, that the same resources and the same energy that founded the Institut Canadien-Français would have been more usefully employed in reshaping the Institut Canadien, and I have several times offered my services in order to achieve this result. It seemed to me that by bringing in a large number of new members one might give the institute a different orientation, and preserve an institution which is prosperous and has reached its 23rd year, a unique occurrence in Lower Canada. I am still ready to employ all my possible influence as founder to arrive at the same result, if it is still desirable.”

Laberge had never actually read the pastoral letters of 1858 on the Institut Canadien. When he heard of them, he consulted his confessor, “a distinguished priest, who has since become a bishop, and who told me,” wrote Laberge to Bourget, “that, as I was taking no active and public part in the work of the institute, I could without objection remain a member of it, reserving the right to withdraw when it became necessary.” This “distinguished priest” was probably Charles La Rocque, parish priest of Saint-Jean-d’Iberville, 1844–66, and third bishop of Saint-Hyacinthe, 1866–75. Indeed, in the Bourget–La Rocque correspondence concerning the members of the Institut Canadien, one can sense how reticent the parish priest of Saint-Jean-d’Iberville and the future bishop of Saint-Hyacinthe was in face of the uncompromising and inflexible attitude adopted by the bishop of Montreal towards them.

Laberge therefore implored Bishop Bourget to extricate him from his perplexity: “Now, My Lord Bishop, I desire to know where I stand, and I am not sufficiently important to be granted the honour of an interview with Your Excellency at Montreal. Although a member of the institute, I continue to receive the sacraments, on the strength of the consultation reported above.”

Whatever the bishop of Montreal’s reply was – if he replied at all – Charles Laberge, although he ceased to be a member of the Institut Canadien, remained faithful to the last to the position that had made him, according to Oscar Dunn, “with due allowances,” “the Montalembert of his party, associating modern ideas on Church and State with solid religious convictions, a democrat as much as a Christian”; “I do not know what the foundation of his liberalism was,” Dunn added, “but he had the hopes of the convinced Catholic.”

The day after his death, on 3 Aug. 1874, his successor in the office of Le National wrote in the paper that had received the last productions of his pen: “He remains a model politician, and he has always been the living proof that one could be a sincere liberal and a fervent Catholic.”

[The newspapers on which Laberge collaborated, Le Franco-Canadien (Saint-Jean-d’Iberville), Le National (Montréal) and L’Ordre (Montréal), must be consulted for any thorough study of him. See also: L’Avenir (Montréal), 2 juin–30 oct. 1849 and L’Opinion publique (Montréal), 27 août 1874. p.s.]

ACAM, 901.135. Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer, 220. L.-O. David, Souvenirs et biographies, 1870–1910 (Montréal, 1911), 43–49. Oscar Dunn, Dix ans de journalisme, mélanges (Montréal, 1876), 229–41.

Cite This Article

Philippe Sylvain, “LABERGE, CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/laberge_charles_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/laberge_charles_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Philippe Sylvain |

| Title of Article: | LABERGE, CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | April 24, 2025 |

![[Hon. Charles Joseph Laberge] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis Original title: [Hon. Charles Joseph Laberge] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis](/bioimages/w600.4252.jpg)