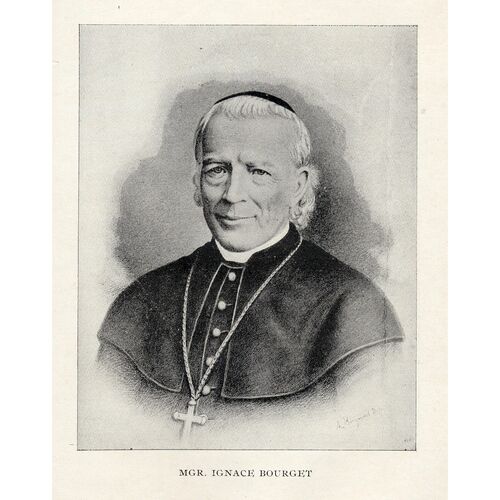

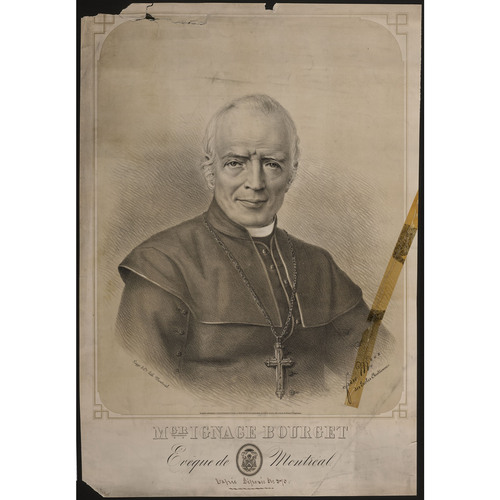

BOURGET, IGNACE, Roman Catholic priest and bishop; b. 30 Oct. 1799 in the parish of Saint-Joseph (now in Lauzon), Lower Canada, son of Pierre Bourget, a farmer, and Thérèse Paradis; d. 8 June 1885 at Sault-au-Récollet (Montréal-Nord), Que.

Ignace Bourget’s forebear, Claude Bourget, was originally from the Beauce region around Chartres, France. On 28 June 1683 at Quebec City he married Marie, the daughter of Guillaume Couture*, a former donné of the Society of Jesus and a companion in captivity of Isaac Jogues*. Ignace was the eleventh of 13 children and in 1811, after a primary education about which little is known, he entered the preparatory class at the Petit Séminaire de Québec. His brother Pierre, who was 13 years older than he, had preceded him at the seminary and was ordained priest on 4 June 1814. Ignace proved a studious pupil but his assiduity did not earn him the highest academic rank. One of his fellow students was Étienne Chartier*, who was to become notable as “chaplain to the Patriotes,” and his teachers included Charles-Joseph Ducharme*, subsequently a parish priest and founder of the Petit Séminaire de Sainte-Thérèse, and Antoine Parant*, later spiritual director and procurator of the Séminaire de Québec.

A pious youth, Bourget was admitted to the Congrégation de la Sainte-Vierge in 1812. Being clearly destined for the priesthood, he was tonsured on 11 Aug. 1818 in the cathedral at Quebec City and by the next month was at the Séminaire de Nicolet, where for three years he studied theology and taught first and second year classes in Latin elements and Syntax respectively. Joseph-Octave Plessis*, the archbishop of Quebec, conferred minor orders upon him on 28 Jan. 1821 and, at the parish church of Nicolet on 20 May, the subdiaconate. The next day Bourget left to assume his new appointment as secretary to Jean-Jacques Lartigue*, the auxiliary bishop at Montreal. He received the diaconate at the bishop’s residence in the Hôtel-Dieu on 22 Dec. 1821 and was ordained priest on 30 November the following year.

The tasks facing the new priest soon multiplied. In addition to his duties as secretary to the bishop, Bourget took on supervision of the building of the episcopal residence and of the church of Saint-Jacques, the corner-stone of which was blessed on 22 May 1823. Construction, carried on at a brisk pace, was completed two years later and Archbishop Plessis consecrated the church on 22 Sept. 1825. Bourget was then appointed first chaplain of Saint-Jacques where he was responsible for organizing the pastoral ministry and seeing to the conduct of public worship. He also directed the Grand Séminaire Saint-Jacques which was housed with a primary school on the ground floor of the episcopal residence; there were never more than 20 students studying theology.

The duties entrusted to Abbé Bourget matched the complete confidence Bishop Lartigue had in his secretary. From the outset the young priest determined to be the unwavering disciple of the bishop, whose thinking reflected the ultramontane teachings to which such writers as Joseph de Maistre and Hugues-Félicité-Robert de La Mennais had recently attracted a great deal of attention in Europe, and whose authoritarian character was ill adapted to ambiguous situations and compromises. Thus it pained Lartigue to see his episcopal authority thwarted at times by the jurisdiction exercised over Montreal Island since the 17th century by the Sulpicians in their capacity as seigneurs and pastors of the single parish of Notre-Dame. He also found it scarcely tolerable that his superior, the archbishop of Quebec, was not more energetic in upholding the rights of the church with the civil power because he lacked boldness in his relations with the governors. “In the 70 years of conquest,” Bourget wrote on 16 Jan. 1830, “religion in this country has almost always lost the advantage through fright, and I very much fear that we are not cured of it yet.”

It was because Bourget showed himself to be Lartigue’s spiritual heir and increasingly shared his views concerning church government that the bishop decided to propose him as his successor to the episcopal see in which he had been enthroned on 8 Sept. 1836. But this candidature, when it was submitted to Pope Gregory XVI, met with the opposition of the Sulpicians, who saw Bourget as an adversary because he shared Lartigue’s suspicion of them, as well as that of certain parish priests in the Montreal region [see Jean-Baptiste Saint-Germain*]. These priests held that Bourget lacked the attainments essential for a bishop in an environment where there were many Protestants and considered him too preoccupied with rules and the minutiæ of discipline. But Pope Gregory overruled these objections and by an apostolic brief dated 10 March 1837 appointed Bourget bishop of Telmesse in partibus infidelium and coadjutor to the bishop of Montreal with right of succession. He was consecrated on 25 July in the cathedral of Saint-Jacques by Lartigue, assisted by Bishop Pierre-Flavien Turgeon*, the coadjutor of Quebec, and Bishop Rémi Gaulin*, the coadjutor of Kingston, Upper Canada.

Lower Canada was then passing through a difficult period. Faced with the rebel agitation in the Montreal region, Lartigue took a stand against the partisans of his cousin Louis-Joseph Papineau*. In a pastoral letter of 24 Oct. 1837 he resorted to the arguments of Pope Gregory’s encyclical Mirari vos of 15 Aug. 1832 which condemned the propositions, deemed revolutionary, that La Mennais, who had shifted from ultramontanism to liberalism, had developed in his Paris paper L’Avenir. The young coadjutor, a model of loyalty to his hierarchical superior, adhered with the full force of mind and heart to the views expressed in the encyclical. This document provided the traditionalist and authoritarian answer to the great problem confronting the Roman Catholic Church since the beginning of the century: what attitude should be adopted to the world born of the intellectual and political revolution of the 18th century and particularly of the régime of civil and religious liberties proclaimed in the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.” Here, as Bourget himself later clearly indicated in his opposition to the liberal arguments of the Institut Canadien, was, at its origin, the explanation of the stance he would maintain throughout his episcopate.

But for the moment Bourget had to deal practically with the spiritual needs of a Catholic population scattered across a vast area bounded by James Bay on the north, the United States on the south, the border between Upper and Lower Canada on the west, and a line on the east which was halfway between Montreal and Quebec. Bishop Lartigue’s declining health forced the coadjutor to undertake more and more of the administration of the diocese, which had 79 parishes, 34 missions at widely dispersed points, particularly in the Eastern Townships, and four missions to the Indians. With a total of 186,244 adherents of whom 115,071 were communicants, the diocese had 22,000 Catholics in Montreal itself – two-thirds of the town’s inhabitants.

To inform himself as fully as possible of the needs of the diocese, Bourget set out to visit it. From 1 June to 14 July 1838 he was received by 16 parishes, and from 21 May to 5 July of the following year by a like number. In 1839, with the assistance of the Jesuit Jean-Pierre Chazelle*, rector of St Mary’s College near Bardstown, Ky, he instituted a retreat for his priests; the success of this endeavour led him to make such week-long retreats an annual event. Thus, when Lartigue died on 19 April 1840, Bourget inherited a task with which he was thoroughly familiar. The plans conceived by Lartigue were to be realized by the person who had inherited both his see and his spirit.

In the autumn of 1840, as he continued to explore his vast diocese, Bishop Bourget went to the north shore of the Ottawa River. Its flourishing lumber industry [see Philemon Wright*] and the dynamism of some 5,000 settlers prompted him to lay the foundations of eight new missions, the nucleus of a religious structure which would lead in 1847 to the establishment of the diocese of Bytown (Ottawa).

To meet needs whose magnitude would have discouraged anyone else, the bishop of Montreal first consolidated the means already available to him. In November 1840 the training of ecclesiastics, conducted since 1825 in haphazard fashion at the Grand Séminaire Saint-Jacques, was entrusted to the Sulpicians of the Petit Séminaire de Montréal. A hospital was required at Saint-Hyacinthe: he detached four religious from the Hôpital Général to form a new community of Sisters of Charity. Bishop Lartigue had long wanted to establish a religious journal independent of politics. This project was realized in December 1840 when the Mélanges religieux began publication in Montreal under the direction of Abbé Jean-Charles Prince*, superior of the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe.

Up to this point the bishop of Montreal had called upon the internal resources of the diocese. In the period 1840–42 the preaching of Bishop Charles-Auguste-Marie-Joseph de Forbin-Janson*, a Bourbon supporter who had come to North America from France in 1839, marked the beginning of a contribution from elsewhere which would grow in the coming years. French-speaking circles in North America, from Louisiana to Lower Canada, in turn heard this fervent Legitimist. He gave free rein particularly in the Montreal region to a stirring eloquence which did not disdain the spectacular methods used in France during the celebrated Restoration missions 20 years earlier, and which now resulted in the erection of a gigantic cross – “the tallest and most beautiful in the world,” as he proudly asserted to a compatriot – on Mount Belœil in October 1841. Less conspicuous but more lasting effects resulted from a trip Bourget made to Europe that year, from 3 May to 23 September. Personnel had to be recruited for the parishes to be supplied, the schools and colleges to be founded, the missions to be established or strengthened. In addition, thought had to be given to setting up an ecclesiastical province in order to unify the administration of the Canadian dioceses under a presiding metropolitan. The shortage of priests was a particular concern of the bishop of Montreal. The situation in Lower Canada had, it is true, improved since 1830. Nevertheless the diocese of Montreal, where needs were pressing and where Protestant proselytism had been making headway because of the presence of Swiss evangelical missionaries since 1834 [see Henriette Odin*], was in a less advantageous position than the diocese of Quebec.

Bourget’s voyage overseas was fruitful. It coincided with the religious revival which was kindled in France during Louis-Philippe’s reign by such men as Henri Lacordaire, Prosper Guéranger, Montalembert, and Louis Veuillot, and which inspired great fervour and rededication. Religious congregations of men and women grew rapidly. Thus in the course of his trip Bishop Bourget could channel towards his own diocese this swelling tide of apostolic activity; such indeed was the hope expressed by Veuillot’s Paris newspaper, L’Univers, in its issue of 23 June 1841, when it learned that “Mgr de Montréal” had “come to Europe to seek a reinforcement of workers for the gospel.”

Although the recruitment of secular priests met with a somewhat disappointing response from the bishops, apart from three Sulpicians who arrived in Montreal in the autumn of 1841, the religious congregations reacted enthusiastically to Bourget’s invitation. On 2 Dec. 1841 six Oblates of Mary Immaculate, four fathers and two brothers, landed in Canada [see Jean-Baptiste Honorat*]; on 31 May the next year it was the turn of the Jesuits, with six fathers and three lay brothers headed by Father Chazelle; on 26 December some sisters of the Society of the Sacred Heart of Jesus arrived to take over the direction of a school at Saint-Jacques-de-l’Achigan (Saint-Jacques); and finally, on 7 June 1844, four Sisters of Our Lady of Charity of the Good Shepherd from Angers came to give assistance to their colleagues who had already arrived in Montreal [see Jacques-Victor Arraud*].

Ably assisted by these reinforcements, Bourget added indigenous foundations: the Sisters of Charity of Providence (Sisters of Providence) [see Marie-Émilie-Eugénie Tavernier*], the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary [see Eulalie Durocher*], the Sisters of Mercy [see Marie-Rosalie Cadron*], and in 1850 the Sisters of St Anne [see Esther Sureau, dit Blondin]. With the assistance also from 1844 of Bishop Prince as coadjutor, he was thus in a position to give a decisive stimulus to his diocese. A French priest, Abbé Charles-Étienne Brasseur* de Bourbourg, who during an enforced idleness in the Séminaire de Québec in 1845 made a study of the situation in Canada, could not resist comparing “the progress characteristic of great things” in the diocese of Montreal “under the influence of its bishop” with the inertia of the diocese of Quebec, which “has been merely existing, and vegetating like a sapless plant since the death of M. Plessis.”

Bourget, whom a new pope, Pius IX, was to regard as the guiding spirit of the Canadian episcopate (as he said in confidence in 1847 to the founder of the Oblates, Bishop Charles-Joseph-Eugène de Mazenod), was not satisfied merely with promoting fruitful developments in his own diocese. He worked actively for the realization of projects that concerned the Canadian church, such as the establishment of the ecclesiastical province of Quebec, erected by a papal bull of 12 July 1844, and the conferring of the pallium on the metropolitan, Archbishop Joseph Signay*, a ceremony over which he presided on 24 November in the cathedral at Quebec.

Canada West also received his attention and watchful zeal. It was partly due to him that the diocese of Toronto, detached from that of Kingston, was created in 1841, and endowed with a cathedral which he consecrated on 29 Sept. 1848. Bishop Gaulin, who was unable to provide adequately for the administration of the diocese of Kingston, had received Bishop Patrick Phelan* as a coadjutor in 1843; the city of Kingston itself, chosen to be the capital of the Province of Canada, had little in the way of Catholic education and assistance to the sick. Accordingly Bourget invited the Congregation of Notre-Dame to set up a primary school in Kingston [see Marie-Françoise Huot*]. He also asked the Religious Hospitallers of St Joseph from the Hôtel-Dieu at Montreal to establish a hospital for the town and surrounding district; this was carried out in September 1845. On 12 February that year Bytown had received a group of Grey Nuns [see Élisabeth Bruyère*], this community having in the previous year sent a contingent of its members to the Red River region [see Marie-Louise Valade*], again at the prompting of Bourget.

The mere enumeration of these achievements is an eloquent testimony to the enthusiasm and energy of the tireless bishop. But his innovative measures both inside and outside his own diocese had in the end displeased his hierarchical superior, Archbishop Signay of Quebec, who was a procrastinator and little given to breaking new ground. Bourget had suggested to him in December 1844 that he should call a first provincial council in order to demonstrate that the title of archbishop was not merely honorific and that an important responsibility was attached to it. Signay was stung and his inertia became stubbornness. At the end of his tether, Bourget decided to go once more to Rome. There, with the encouragement of Abbé Charles-Félix Cazeau, the archbishop’s secretary, he sought – albeit in vain – his superior’s resignation; he had already, with brutal frankness, written to Signay himself on 25 Sept. 1846: “For a long time I have been thinking that Your Grace should give up the administration of your archdiocese, contenting yourself with retaining the title of metropolitan. I shall use the occasion of my journey to Rome to put before the Holy See the reasons leading me to believe that it might be time for you to relieve yourself of this burden.” Indeed in his opinion there were problems pending which only a concerted effort of the bishops in a provincial council could solve: non-observance of rituals, a complete revision of the catechism manual, and any number of other improvements in the organization of the Canadian church were all needed.

This second journey, in 1846, during which Bourget witnessed with delight the delirious demonstrations in Rome in favour of Pius IX, who had just succeeded the unpopular Pope Gregory, brought results as impressive as had his first. The decision was taken to create the diocese of Bytown, and its first bishop was his own candidate, Joseph-Bruno Guigues*, the superior in Canada of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. Moreover, Bourget returned with some 20 labourers for the faith: his repeated invitations brought responses from the Congregation of the Holy Cross [see Jean-Baptiste Saint-Germain], the Clerics of St Viator [see Étienne Champagneur], the Jesuits, and the Sisters of the Society of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. When the great epidemic of 1847 swept Montreal, Bourget was able to detach several priests from his reinforced team to go to the aid of those stricken with typhus. He himself set the example and was fortunate to escape the ravages of the disease, unlike the nine priests and 13 religious sisters who were victims of their own dedication.

By the dawn of 1848 Bourget was justified in believing that the prediction he had shared with Bishop Turgeon in the dark days of 1837 had come true: “The people, seeing their clergy take up their interests at a time when their previous leaders abandon them to the mercy of an authority which they have insulted out of ignorance, will recover their feelings of affection and trust towards their pastors.” During the decade just ended, a swing back towards the clergy had indeed occurred and the practice of religion had noticeably improved: the moving addresses of Bishop de Forbin-Janson had stirred hearts and minds, and the new clergy from Europe had sustained and consolidated the effects of his preaching. Moreover, one of the greatest paradoxes of this troubled period was the result produced by the French Canadian Missionary Society [see Henriette Odin], founded by English-speaking Protestants of Montreal in 1839, shortly after the ill-fated rebellion, to take advantage of a situation unfavourable to the Catholic clergy in order to recruit adherents. In fact, contrary to the expectations of the society’s promoters, this same clergy, when put on the alert, made every effort to counteract the activity of the Swiss missionaries effectively and to recover “by dint of good offices,” as Bourget had urged, the trust of the people which had been temporarily shaken. By 1848 “Christianization,” to use the bishop’s word, had gradually permeated all levels of French Canadian society. Religious congregations of men and women were given an increasingly important role in primary education, while the clergy, through the classical colleges which were under its sole direction, ensured the recruitment and training of the élite of the middle class. At the same time, the people of the towns, countryside, and settlements were fitted with a solid organization by parish priests and missionaries. Hospital and charitable assistance was dispensed by religious hands. Finally the Mélanges religieux, the Canadian counterpart of L’Univers though without the talent, and the Œuvre des bons livres, a library established in 1844 in Montreal [see Joseph-Vincent Quiblier*] on the model of one at Bordeaux and recognized in a pastoral letter of 20 Sept. 1845, proposed to inculcate “good principles” and sound doctrines.

These accomplishments were the fruit of unceasing labour. In the habit of allowing himself no more than five hours’ sleep a day, Bourget seemed to contemporary witnesses to have taken a vow to waste no time. A man of action and authority, he nevertheless, like the most industrious and versatile of authors, left an impressive number of published and manuscript works. These manifest an extraordinary dedication to the task of composition, especially given that the written word never came easily to him. Bourget always commenced his pastoral letters well ahead of time and repeatedly revised his texts before sending them to the printer. Heavily burdened with all manner of tasks and worries, the bishop was none the less easy to approach. Even the inopportune visitor did not seem to irritate him. In intimate gatherings he had an inexhaustible fund of conversation and never missed the chance to make a teasing remark or to enjoy the apt retort, even at his own expense.

The prelate made an impression whenever he performed his episcopal duties. His mitre crowning his prematurely white hair, he would stride rather abruptly into the church to participate in liturgical rites with impressive dignity. When he undertook to speak, the conviction which enlivened his remarks made his lively blue eyes sparkle all the more and gave to his even features a ruddier hue.

The Roman liturgy which Bourget introduced into his diocese matched his reverence for the papacy, his exacting sense of order, and the effusive piety which fitted well with ultramontane devotional celebrations. Thanks to him, the formality and sedateness of the services conducted by the Sulpicians in Montreal, a true city of the north, gradually gave way to the Mediterranean warmth of Roman rites. As a result, new importance was accorded to gestures, to the public image, and to gatherings for magnificent ceremonies in immense churches. One thinks of the spectacular celebrations at Notre-Dame in Montreal when the Zouaves were departing, and the financial sacrifices that Bishop Bourget unhesitatingly imposed on his diocesan flock in order to erect a cathedral reminiscent of St Peter’s in Rome. A similar emphasis was placed on processions, confraternities, the veneration of innumerable relics brought back from Rome (that “great reliquary,” as he liked to term it), the observance of Forty Hours which he introduced to his diocese on 21 Feb. 1857, and such highly emotional devotions as those to the Seven Sorrows of Mary and to the Sacred Heart. As for the strict moral discipline applied in admission to the sacraments, this was softened as a result of the adoption in the Montreal diocese of the Ligourian ethical rules, as laid out by Bourget in his memorandum to the clergy on 25 July 1871: “Yes, St Alfonso has always been regarded as the [spiritual] director of this diocese, and his moral doctrines have always resolved the difficulties that were encountered in the course of the sacred ministry.”

A churchman whose reputation for saintliness soon spread throughout the diocese, and whose sympathy and compassion for the moral and physical distress visible in Montreal, a city then experiencing rapid urbanization and the growth of a working class, Bourget was also a patriot whom the events of 1837 anchored to a conservatism antipathetic to any political or social adventure. It is significant that when the Institut Canadien, at the instigation of Jean-Baptiste-Éric Dorion*, founded on 5 April 1848 the Association des établissements canadiens des townships, the chairmanship of the central committee was given to Bourget, while Louis-Joseph Papineau had to be content with the vice-chairmanship. But in September the bishop resigned, and although the association survived it fell prey to ideological and political conflicts. No compromise was possible between the Ultramontane and the liberal, between the undisputed leader of his clergy as well as to a lesser but real degree of the conservative middle class which had rallied to the Reform party of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* and Robert Baldwin*, and the former Patriote chief who since his return from exile had vehemently demanded the “repeal of the Union,” a local variation of the liberal principle of “nationalities” (self-determination).

Following Papineau’s example, the contributors to L’Avenir, a paper that began in July 1847 in Montreal, stood more and more aloof from the Reform majority. One of them, Papineau’s nephew, Louis-Antoine Dessaulles*, moving in the wake of his uncle, proved a determined adversary of responsible government. Throughout May 1848 he argued passionately in L’Avenir that “the Union is undeniably the most flagrant injustice, the most infamous outrage upon our natural and political rights that could be perpetrated.” The February revolution in Paris, and more importantly the seditious turn of events in Rome, inflamed men’s minds. Pius IX, having shaken off his fleeting inclination towards liberalism after refusing to declare war on Austria for the liberation of the peninsula, had aroused the anger of the Italian patriots, and in face of the revolutionary ferment he deemed it prudent to flee Rome and take refuge in the kingdom of Naples. The question of the temporal power of the pope was from this moment a real one. The pope having failed to take up his task as leader of the national movement, the Roman republic, proclaimed on 5 Feb. 1849, took over the government of its territory by virtue of the right of a people to self-determination.

Bourget had not been slow to draw the parallel between the upheavals in Europe and the articles in L’Avenir that he termed “revolutionary.” In his pastoral letter of 18 Jan. 1849 ordering “prayers for our Holy Father Pope Pius IX,” he came down firmly on the side of the government against the supporters of Papineau and L’Avenir: “What recommendations can we make to you in order to escape the calamities that are besetting so many great and powerful nations? Here they are in brief: Be faithful to God and respect all legitimately constituted authorities. Such is the will of the Lord. Do not listen to those who address seditious remarks to you, for they cannot be your true friends. Do not read those books and papers that breathe the spirit of revolt, for they are vehicles of pestilential doctrines which, like an ulcer, have corroded and ruined the most successful and flourishing states.”

The news of the proclamation in Rome of the Mazzini republic gave the young contributors to L’Avenir the chance to define their own position clearly: they were determined to draw all the logical inferences inherent in the liberal principle of nationalities. On 14 March 1849 they declared themselves against the maintenance of the temporal power of the pope with a bluntness reinforced by their observation that the clergy, headed by the bishop, sided openly with their political opponents. “Those of our readers who feel keenly the beauty and truth of the principles we are defending, will,” their spokesman asserted, “understand our insistence, knowing that this revolution in Italy is the occasion for incessant attacks against democratic principles, coming from sources which are even more to be feared because they are more respectable.”

There was no better way to cement the alliance between the clergy and the La Fontaine-Baldwin party. Through fear of possible upheavals, religion became the bulwark of political and social order. The Reform party, soon to call itself the Liberal-Conservative party, obtained appreciable political advantages from the clerical influence thus placed at its disposal. On the other hand their more liberal opponents, nicknamed the Rouges because of their radical arguments for the abolition of tithes, the secularization of education, the separation of church and state, and, on the strictly political side, annexation to the United States, attracted the persistent and unrelenting opposition of this same clergy, and especially of Bourget, particularly from the moment when the L’Avenir group seized control of the Institut Canadien, that is, in 1851.

The bishop of Montreal continued his tireless efforts in the field of social action. Because the first association set up to encourage the settlement of the Eastern Townships had failed to attain its goals in the circumstances already mentioned, Bourget personally took over the project, being behind the second association, dedicated to the same purpose, which the Canadian bishops recommended at their assembly in Montreal on 11 May 1850. Intemperance was a social evil in French Canada at that period. He entrusted the struggle against this scourge to the eloquence of Abbé Charles-Paschal-Télesphore Chiniquy* and in 1853 he founded the Annales de la tempérance at Montreal. His zeal encompassed the poor: convinced that each parish ought to see to their needs, he encouraged, with this intention, the expansion of the St Vincent de Paul Society, presiding over the founding of the Montreal conference on 19 March 1848. Among other unfortunates, the deaf-mutes required assistance: in 1850 there were about 1,100 in French Canada, 400 of whom lived in Montreal. For them, Bishop Bourget established the Hospice du Saint-Enfant-Jesus at Côte-Saint-Louis (now part of Outremont), and entrusted its management to Abbé Charles-Irénée Lagorce*, who was shortly succeeded by the Clerics of St Viator. The fire in Montreal on 8 July 1852, which destroyed 1,100 houses as well as the cathedral and the bishop’s palace and which left about 10,000 destitute, grieved him deeply, and his words at the time testify to the charity and compassion he brought to all tragedies and disasters. By the role he played in social action he helped to sustain an ongoing broad movement of moral and religious renewal.

To his concern for these adversities was added his apprehension about the Institut Canadien, which since its foundation in 1844 had become increasingly influential in every sphere of French Canadian life, political, social, or religious. This institute brought together the young intellectual élite of Montreal to discuss the most advanced ideas of the time, and its library had been built up with no obvious regard for the rules of the Index of Forbidden Books. Bourget judged the institute eminently subversive of the moral and spiritual well-being of his flock and believed it expedient to issue a first warning. At the second provincial council, held in Quebec City in June 1854, he used his influence with the other bishops to get a disciplinary regulation drawn up indicating to the priesthood and the faithful the attitude to be adopted towards “literary institutes.” Its explicit text was clearly aimed at the Institut Canadien: “When it is an established practice that a literary institute has books harmful to faith or morals, that readings are given there which are anti-religious, that immoral and irreligious newspapers are read there, one cannot admit to the sacraments those who are members of it, unless there is reason to hope that, given the strength of good principles, they may continue to effect reforms within [the institutes].”

This document, dated 4 June 1854, did not prevent the institute from getting 11 of its members elected to the Legislative Assembly that summer. Its success allowed “the brilliant pleiad of 1854,” as Arthur Buies* called it, to abandon pure speculation for action, having been restricted heretofore to the institute’s own platform or to Le Pays, which had replaced L’Avenir two years earlier. While Charles Daoust*, the member for Beauharnois and editor of Le Pays, demanded in his paper the separation of church and state, Joseph Papin*, the member for L’Assomption, constituted himself the interpreter in parliament for his liberal colleagues with the aim of obtaining a particularly important consequence of that separation, nondenominational schools.

No doubt contemplating future battles against those who held these views, which could not but give offence to him as an Ultramontane, Bourget set off a third time for Rome, on 23 Oct. 1854. Turgeon, the archbishop of Quebec, who had succeeded Signay at his death on 3 Oct. 1850, had invited him to represent the ecclesiastical province at the proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, set for 8 December. Bourget spent his leisure in Italy and France studying in detail the particular characteristics of the Roman liturgy, which tine Benedictine Prosper Guéranger had been zealously restoring in France since 1840, and in 1856 he published in Paris a substantial volume of 569 pages entitled Ceremonial des évêques commenté et expliqué par les usages et traditions de la sainte Eglise romaine avec le texte latin, par un évêque suffragant de la province ecclésiastique de Québec, au Canada, anciennement appelé Nouvelle-France. He presented complimentary copies of his book to all the bishops of France, a courteous gesture which did not, however, make the work a best-seller; it was seldom read. Nevertheless, when Bourget returned to Montreal on 29 July 1856, he hastened to apply to the last detail the conclusions he had drawn from his newly acquired erudition in liturgy. In his ultramontane fervour he sometimes acted with a haste and intransigence which ran counter to what certain subordinates such as Abbé Charles La Rocque*, parish priest of Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu), believed feasible, and to their conviction that one should not sweep away time-honoured usages. Probably realizing that the young generation of ecclesiastics would be more receptive to his views, Bourget wanted the Séminaire de Montreal to adopt manuals of Roman theologians instead of those of the Gallican Jean-Baptiste Bouvier being used by the Sulpicians The bishop regretted “that here as in France, the Society of Saint-Sulpice, which in many ways is so worthy of respect, is not at the head of this splendid movement which is taking place throughout the world in favour of the sound doctrines of Ultramontanism.” Even the details of priestly garb were not a matter of indifference: in 1858 he made it obligatory for his clergy to wear the Roman collar instead of the French band. Finally, as one more of the indirect results of his last voyage to the banks of the Tiber, his cathedral, destroyed by fire in 1852, was to be rebuilt on no less a model than St Peter’s in Rome.

His nearly two years overseas reinforced Bishop Bourget’s ultramontane convictions. What he saw in Italy, in the state of Piedmont which had remained clerical for so long and where the liberals had since 1850 been pursuing their task of secularization, contributed in no small measure to confirming his aversion to liberalism. Back in Montreal, he found himself again confronted by those liberals whose principles and activities had seemed so detestable to him in Europe. But he did not act immediately.

To counteract the influence of the Institut Canadien, a group of its moderate members had in 1852 started a rival association, the Institut National, which they had placed under the patronage of the bishop of Montreal; its success had not, however, lived up to the expectations of the founders and their protector. On 2 Feb. 1857, no doubt thinking that they would be more fortunate, the Sulpicians set up the Cabinet de lecture paroissial with spacious premises near the Place d’Armes, “in opposition to the Institut Canadien” according to a contemporary, Laurent-Olivier David*; a literary centre which was attached to it in October subsequently became the Cercle Ville-Marie. In September 1854 the Jesuits, who had founded the Collège Sainte-Marie in 1848, had forestalled the Sulpicians in the battle against the common foe by setting up in their college the Union Catholique, first a congregation and then an academy, which on 23 Nov. 1858 started the newspaper L’Ordre espousing the views of Louis Veuillot [see Cyrille Boucher*].

Whether or not the two enterprises, Sulpician and Jesuit, had produced the anticipated results, Bishop Bourget decided to take drastic action. He did so in three pastoral letters on 10 March, 30 April, and 31 May 1858, which followed a well-developed plan. In the first letter, he described the disastrous effects of the French Revolution and, generally, of all revolutions, which he attributed to the circulation of evil books; in the second, he indicated that revolutionary propaganda could be prevented in Canada through the enforcement of the rules of the Index; and in the third, he stigmatized those whom he considered the harbingers of revolution in Canada, the liberals of the Institut Canadien.

The institute, brought under attack by the first pastoral letter, in which it was likened to “a seat of pestilence” for the whole country, met on 13 April. The majority of its members, in accord with the liberalism it professed, refused to yield to the bishop’s threatening text. Indeed, for a liberal, each person has the power to choose his intellectual sustenance as he wishes; cases of poisoning that may result are merely accidental inconveniences, amply compensated for by a higher good: liberty. But the minority, following its leader Hector Fabre*, although as desirous as the radical majority of not finding itself under the thumb of the clergy, was ready to compromise. Fabre and his friends realized that most of the institute’s members lacked the necessary maturity and culture to tackle indiscriminately the reading of certain works in their association’s library. They believed “that if society has the right to regulate the sale of poison, the institute should have the right to forbid its members to poison themselves.” Since no agreement could be reached, a separation followed. On 22 April 1858, 138 of the some 700 members tendered their resignations to the president of the Institut Canadien, Francis Cassidy*. On 10 May they formed an opposing association which they named the Institut Canadien-Français.

In his second pastoral letter, dated 30 April, Bishop Bourget called the Institut Canadien specifically to account. “Against the evil books” in its library he brought forward the rules of the Index. The summons was to submission, otherwise “it would follow that no Catholic could henceforth belong to this institute; that nobody could read the books in its library, and that no one could in future attend its sessions or go to listen to its readings,” for by virtue of the regulations of the Council of Trent the mere fact of possessing, reading, selling, or passing on prohibited books was so grave an offence that it resulted ipso facto in excommunication.

Having dealt with the library of the institute and its readers, the bishop of Montreal in his third letter attacked the principles of its leaders. Wishing to make his censure of French Canadian liberalism as authoritative and effective as possible, he took his arguments from the encyclical that had determined the direction of his thinking once and for all at the beginning of his priestly career, Gregory XVI’s Mirari vos. Using this blunt pontifical text, he accentuated its forcefulness by giving it an extreme interpretation whose categorical and absolute precepts can only occasion profound astonishment today. Having censured liberal views he turned to the newspaper which transmitted them, Le Pays. After singling out amongst the “bad papers,” the “irreligious paper,” the “immoral paper,” and the “heretical paper,” Bourget came to the anticlerical paper; this he termed “impious,” for “each priest being the representative of Jesus Christ,” and “the authority which is vested in him being that of Jesus Christ himself, any attempt to destroy the influence of the clergy is tantamount to attacking this divine authority.” Clearly, for the prelate’s pen the “impious paper” was another term for the “Liberal paper,” since the Liberals had always been opposed to clerical interference in the political sphere. Indeed Bourget himself immediately confirmed this identity: “The Liberal paper is the one that claims, among other things, to be free in its religious and political opinions; that would like the church to be separate from the state; and that in a word refuses to recognize the right of religion to have anything to do with politics, even when the interests of faith and morals are at stake.” In order to prove that “no one is permitted to be free in his religious and political opinions,” the churchman started from the principle that Jesus Christ has “given his church the power to teach all peoples the sound doctrine,” namely “that pure doctrine which instructs them to govern themselves, as all truly Christian peoples must do. Here obviously is a moral point of high import. Now, any moral point comes within the domain of the church and essentially derives from its teaching. For its divine mission is to teach sovereigns to govern with wisdom and subjects to obey in gladness.”

In this way the bishop’s thinking led directly to theocracy, which in the opinion of a contemporary of Veuillot, Abbé Henri Maret, dean of the faculty of theology at the Sorbonne, was the epitome of the social and political doctrine of ultramontanism. And in fact, according to the Ultramontanes, “the Sovereign Pontiff, in addition to his spiritual authority, [which is] sacred for all Catholics, possesses by divine right a true political jurisdiction throughout the world, a jurisdiction which renders him an arbiter of the great social and even political questions; and, in certain respects, kings and heads of nations are only his deputies.” From this theocratic principle follow “social and political privileges for the clergy of each nation,” and the fact that “civil intolerance is raised to the rank of religious dogma.”

The intransigence of the bishop clashed again with the intransigence of the liberals over the war launched by Piedmont which was the start of the unification of Italy. From 1859 Austria was gradually forced out of the Italian peninsula: principalities and the kingdom of Naples disappeared, the Papal States broke up, and the kingdom of Italy was brought to completion by virtue of the principle then entering into international public law: the right of peoples to self-determination.

For Catholics these dramatic years were a distressing period. In their view the movement for the unification of Italy was nothing short of a concerted attempt on the part of forces hostile to the Roman Catholic Church to reduce it to impotence. Nobody was more convinced than the bishop of Montreal. Consequently, from 1860, he sent out an increasing stream of pastoral letters and memoranda to his clergy concerning “the independence and inviolability of the Papal States.” For him the revolution was first attacking the papacy “in order next to overthrow unimpeded the rest of the universe,” including Canada, where liberal books and newspapers were serving as a means of spreading the “forces of evil.” Le Pays, whose editor after 1 March 1861 was Louis-Antoine Dessaulles, was naturally a target, as is apparent from the seven long letters ablaze with ultramontane fervour which Bourget addressed to the newspaper in February 1862. The owners of the liberal paper having refused to publish them, Dessaulles replied to the bishop on 7 March. In the course of his remarkably lucid letter, he came to the central problem which divided Ultramontanes and liberals: which group would impose its ideology on the community? He had suspected that the bishop of Montreal wanted “to intermingle the spiritual and temporal spheres, in order to control and dominate the latter by means of the former,” while the ambition of the “laymen” was to “avoid confusion between these two orders of ideas” and to require “that the spiritual order be entirely distinct from the temporal order.” He concluded: “In a word, my lord, in the purely social and political order we insist on our entire independence from the ecclesiastical power.”

The apprehensions of Dessaulles and those who shared his liberal convictions about the crushing preponderance of the ecclesiastical structures in French Canadian society, particularly in the Montreal region, can be understood in the light of facts about Bishop Bourget’s diocese in this period. (These are taken from historian Serge Gagnon.) The diocese had 128 parishes and 322 priests to serve a Catholic population of 342,654, of whom 210,654 were communicants: hence one priest for every 1,064 persons or 623 communicants. Of this total, 121 parish priests and 48 curates were assigned to pastoral duties. Thus almost every parish had a resident priest and some 40 per cent of the parish priests were assisted by a curate. About one-third of the clergy exercised their ministry as chaplains or teachers; apart from 52 secular clergy, all of these belonged to the various communities of regular clergy settled in the diocese. The great majority of secular clergy, who did not work at the parish level, taught the 811 pupils of the four classical colleges in the diocese, where many of the 127 candidates for priesthood in the diocese directed classes while pursuing theological studies. The lay religious taught 5,943 boys. “As for the 10 communities of women, they comprise, in addition to 1,033 religious, 148 novices and 152 postulants. Seven of these women’s communities teach 9,705 children. The other three attend to 36,463 poor, sick and infirm, etc.”

The Catholic population, suitably endowed with these structures in large part attributable to the ability and zeal of Bishop Bourget, was on the whole amenable to the directives given by its pastors and committed to the realization of the objectives suggested to it. There is no better indication of this than the recruitment and enlistment of 507 Zouaves, in seven detachments, who went to assist the papacy from 1868. Historian René Hardy, who has minutely analysed all aspects of this important episode of Canadian religious history in the 19th century, estimates that the amount expended in sending the Canadian volunteers to Rome was at least $111,630, no trivial sum since it was raised in years of financial hardship. As historians Jean Hamelin and Yves Roby show, the financial crisis in England and the difficulties of reconstruction after the American Civil War had a negative impact on the economy of Quebec, so that all sectors of the economy were adversely, though unevenly, affected. Most Canadian Catholic bishops were hesitant about fitting out soldiers and instead exhorted their dioceses to contribute to the charity known as Peter’s pence, but thanks to Bishop Bourget, despite all pecuniary and other difficulties, French Canada stood with France, Belgium, Holland, Ireland, and others in recruiting volunteers for the defence of the Papal States. The stakes, already considerable by reason of the objective that was directly and publicly pursued, were perhaps higher still because of the accompanying tactics calculated to disseminate ultramontane ideology throughout the various strata of society. “The function of the Zouaves in clerical strategy as a whole,” writes Hardy, “was principally to legitimate the cause of the Holy See, which the French Canadian clergy used as a pretext to justify its opposition to the section of the bourgeoisie that was contending with it for power. Whatever the needs of Rome might be, Bishop Bourget and his associates wanted Canadians to serve in the pope’s army, for in their judgement these soldiers were an even more powerful means of combatting the ideas diffused by the liberals of Le Pays and of the Institut Canadien than the organizing of public demonstrations and prayers or the circulation of newspapers and pamphlets favourable to the cause. In short, it was a matter of involving the population directly in this struggle of ‘truth against error’ by getting [their] compatriots to fight in it, increasing in this way information favourable to the papal viewpoint, fostering affection for Pius IX by constantly publicizing his misfortunes, arousing fear and hatred for his enemies, and, in the Roman tradition, forging on the battlefields and in the papal city an ultramontane élite which in the future would serve as a bulwark against the introduction into Canada of ‘subversive and revolutionary ideas’ such as those condemned in the Syllabus.”

Concurrently with the expansion of ultramontanism, which the Zouave movement powerfully assisted, liberalism as represented by the Institut Canadien met with one defeat after another. Attempts at reconciliation with the bishop of Montreal in 1864, a petition addressed to Pius IX by 17 Catholic members of the institute in 1865, unfavourable reports by Bourget to the Holy Office in 1866 and 1869, all these proceedings finally resulted in the Annuaire de l’Institut Canadien pour 1868 [see Gonzalve Doutre*] being placed on the Index in July 1869. The Guibord affair [see Joseph Guibord*; Alexis-Frédéric Truteau*], with its succession of sudden developments between November 1869 and 1874, really marked the final decline of the association, even though the Privy Council in London appeared to give victory to the liberals over the ecclesiastical authority. Joseph Doutre in particular, who with Dessaulles was one of the institute’s most influential associates, never forgave the clergy for having subjected him to relentless opposition as a member of it, and especially whenever he aspired to a political role in his country’s government.

This conflict was not the only one in which the bishop of Montreal was involved. An Ultramontane and a churchman par excellence, he was paradoxically led by circumstances to wage exhausting and endless struggles against the two most impressive religious institutions of the Canadian church at that period, the Séminaire de Québec and the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice at Montreal.

The founding in 1852 of the Université Laval by the Séminaire de Québec stemmed from Bishop Bourget’s initiative [see Louis-Jacques Casault*]. But this initiative was based on a misunderstanding. According to the bishop the new university was to be a provincial one for which all the bishops of the ecclesiastical province took responsibility. It was not long, however, before he was forced to sound a different note, since the organization and management of the university were taken over entirely by the seminary and the archbishop of Quebec. An attempt was made to allay Bourget’s apprehensions by introducing an affiliation clause making the extension of university privileges to affiliated institutions possible, but this clause proved inoperative in his diocese. In 1858 none of the local classical colleges was affiliated with Laval, and an application from the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery was twice turned down [see Hector Peltier*]. From 1862 Bishop Bourget thought of establishing another university in his episcopal city. He was impatient to do this because of the increasing numbers of Catholic students who had to enrol in the faculties of law and medicine at McGill College and elsewhere. In 1865 he based an application to Rome on statistics: in 1863–64 Laval had only 72 registered students. Few of those who enrolled came from Montreal, which had 530 Catholic students at the university level, counting those attending the “grand séminaires.” For its part the Séminaire de Québec stressed that in 10 years it had spent more than $300,000 to maintain the university, whose future would be irrevocably compromised by an institution at Montreal. Rome concluded that it was not expedient to create a second university at Montreal. In 1870 Laval suggested a branch in Montreal, but as the authority of its bishop was virtually ignored, Bourget rejected the project. Two years later the Montreal bar started negotiations which came to naught. The Jesuits attempted in their turn to obtain university privileges for the law school of their Collège Sainte-Marie from the government, but the bishop, at Rome’s request, asked them to withdraw their petition [see François-Maximilien Bibaud]. A provisional epilogue in the dénouement of this 25-year university crisis came in a resolution of Propaganda dated 1 Feb. 1876 stating that a branch of the Université Laval should be established at Montreal. The costs were to be paid by Montrealers, but the university authority would remain at Quebec, the bishop of Montreal being at most permitted to approve the appointment of the vice-rector. Bourget, however, tendered his resignation as bishop soon after, and thus avoided having to implement such a decree.

Another conflict, no less bitter, had pitted Bourget against the Séminaire de Montréal over the thorniest problem with which he had to deal as an administrator: the division of the parish of Notre-Dame. At the time of his resignation the feelings aroused by this incident had only just subsided.

“The Parish,” as the expression went, covered all of Montreal Island and in 1864 it had a population of 100,000. Its status had not changed since Bishop François de Laval* had erected the parish of Ville-Marie canonically in 1678, and united it for all time to the Séminaire de Montréal. A few years later an ordinance of Bishop Saint-Vallier [La Croix*] had decreed that the superior of the seminary should be ex officio the parish priest. In 1863 the superior general of Saint-Sulpice in Paris presented a report to the Holy See in which he begged that the established order be maintained. Asked to reply to him, Bourget stated: “I grant that the superior of Saint-Sulpice should be the priest in perpetuity of the parish of Montreal. But, at the same time, I expect him to be entirely subordinate to the bishop. This entire subordination to the bishop on the part of the parish priest of Montreal must be that which is required by the holy canons for the good government of souls.” The two parties were summoned to Rome. The superior proved conciliatory on certain points but adamant as to a method of dismissal for the parish priest; he even threatened the bishop that he would withdraw from Montreal his entire community of 57 priests, of whom 42 were assigned to pastoral ministry. Finally in 1865 the superior accepted the following decisions of Propaganda: the bishop obtained authorization to divide the parish of Montreal; the new parishes would be offered first to the Sulpicians; the parish priest of Notre-Dame would be nominated by the seminary but would receive his investiture from the bishop; he could be dismissed by either the superior or the bishop [see Joseph-Alexandre Bails; Joseph Desautels].

Within the boundaries of the parish of Notre-Dame, Bourget hastened to erect ten new canonical parishes between September 1866 and December 1867. But he had to have them incorporated by the civil authority so that, by virtue of the law, they would have a legal existence. It was on this point that the Sulpicians lay doggedly in wait for him. They urged the government not to recognize the autonomy of the new parishes, which in their eyes were merely succursal chapels of the parish of Notre-Dame. To uphold their cause they could count on the advice of their former pupil, George-Étienne Cartier*, who was then at the summit of his political power, and on the legal skill of a protégé of Cartier, lawyer Joseph-Ubalde Beaudry*, the legal adviser to the council of the parish of Notre-Dame. For his part Bourget had the eminent lawyer Côme-Séraphin Cherrier to assist him. The result was an endless series of disputes, punctuated by frequent appeals to Rome, during the course of which Cartier brought his authority to bear to such an extent that the bishop of Montreal’s patience, legendary though it was, almost reached the breaking point. “What then,” he wrote on 19 Feb. 1871, “is the nub of this inextricable difficulty? It is M. Cartier, who exercises his right to [use] pressure, or rather oppression.”

By this time the battle was raging on all fronts. Le Nouveau Monde, begun in 1867, identified itself with the causes supported by Bourget, who on 28 Sept. 1872 condemned La Minerve, Cartier’s journal, “because of the insults it continually hurls at the editor of Le Nouveau Monde, that is to say at me.” The ultramontane paper had conducted a relentless campaign for four months against the work Beaudry had published at Montreal in October 1870, Code des curés, marguilliers et paroissiens accompagné de notes historiques et critiques. A new St George, Canon Godefroy Lamarche, the editor of Le Nouveau Monde, seems not to have been able to crush the dragon of “Gallicanism” in Beaudry, for in 1872 Siméon Pagnuelo, a young lawyer who was Lamarche’s legal adviser and associate, in his turn published Études historiques et légales sur la liberté religieuse en Canada [see Desautels] which attacked Beaudry’s arguments.

Pagnuelo had already helped draft the Programme catholique [see François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel], which Bourget considered “the strongest safeguard of the true Conservative party and the firmest support for the right principles that must govern a Christian society.” Repudiated by the new archbishop of Quebec, Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau*, the programme struck a blow at the hitherto uncontested authority of Cartier over the Conservative party, and he suffered a resounding defeat in Montreal East in the federal elections of 1872. Bourget denied having contributed to the defeat but this was not the opinion of Charles La Rocque, the bishop of Saint-Hyacinthe, who might be viewed as the prototype of the symbiotic alliance existing between clerics and French Canadian politicians in the 19th century. He wrote to Cartier on 1 Sept. 1872: “May I tell you in friendly fashion that I feel humiliated when I reflect whence came the blow that succeeded in striking you down.” For the Ultramontanes it was evident that the bishop of Montreal, whose golden anniversary of ordination had been celebrated in great style from 27 to 30 Oct. 1872, had finally triumphed over his Sulpician adversaries and their powerful ally, since early in January 1873 all the canonical parishes obtained their civil registration. “The immense popularity of the great statesman,” Bishop Louis-François Laflèche* observed on 31 January, “shattered in Montreal against the firmness of this worthy bishop, like a clay vase against rock.”

Weighed down by so much labour, and often sick, Bourget had secured Canon Édouard-Charles Fabre*, Cartier’s brother-in-law, as a coadjutor. The archbishop of Quebec presided at his consecration on 1 May 1873 in the church of the Collège Sainte-Marie. All the bishops had assembled around the archbishop and Bourget, the dean of the Canadian episcopate.

At first sight this ceremony symbolized a harmony that seemed to exist in the episcopal body. But appearances were deceptive. Archbishop Taschereau, in particular, was not very fond of the bishop of Montreal. As former rector and chancellor of Université Laval he had been unalterably opposed to the attempts to set up another university. On the question of the division of the parish of Notre-Dame, he had often sided with the Sulpicians. But, above all, the extremism of the Ultramontanes in Montreal offended his innate realism, and his close friends did not look kindly upon the “rabid men of Montreal.” He also reproached Bourget for welcoming into his diocese priests whom Quebec had got rid of without regret: the Jesuit Antoine-Nicolas Braun, for example, who on the recent occasion of the 50th anniversary of Bourget’s ordination as priest had delivered in the archbishop’s presence a sermon railing against liberalism and Gallicanism, the archbishop himself, in Montreal eyes, being far from free of their taint. But Taschereau was particularly annoyed about Abbé Alexis Pelletier*. The latter, a Gaumist, had been obliged to resign as auxiliary priest at the Séminaire de Québec, and had taken refuge in the diocese of Montreal. There, from the safe cover of the inner offices of Le Franc-Parleur, a subsidiary of Le Nouveau Monde, he vented his ill temper on Taschereau, the person whom he saw as “the perfect example of domination, arrogant superiority, imperious, arbitrary autocracy, and a cold ill-concealed disdain for any grandeur other than his own.”

The apparent unison among the bishops was shown once more when they published a collective letter on 22 Sept. 1875 denouncing Catholic liberalism, which the Conservatives used as a weapon against their Liberal adversaries. The province was in an uproar. “One hears talk only of politics,” Abbé Jean-Baptiste-Zacharie Bolduc, procurator of the archdiocese of Quebec, observed on 21 Jan. 1876 to his friend Benjamin Pâquet*. Bourget himself entered the fray when a pastoral letter sent with a memorandum to his clergy on 1 February in its turn condemned Catholic liberalism. To his great regret he was unable to form a precise notion of what Catholic liberalism really was: he would have to ask Rome for a definition! The bishop of Montreal attacked those who reviled the clergy, especially the parish priests who deserved respect and obedience: “I listen to my parish priest, my parish priest listens to the bishop, the bishop listens to the pope, the pope listens to our Lord Jesus Christ.” Feeling that this pastoral was “bound to stir up trouble,” the archbishop of Quebec was alarmed. In Taschereau’s immediate circle men like Abbé Louis Pâquet believed Bourget had lost his senses. “Frankly,” he added, “this is the most charitable opinion.” The Capuchin Ignazio Persico, a good observer who had been parish priest of Sillery since 1873, thought too many bishops were ardent political partisans, as he intimated on 20 April 1876 to Cardinal Alessandro Franchi, the prefect of Propaganda: “It is obvious that many bishops not only prove to be party men, but also take matters to extremes; and [they do] this not to defend religious values but simply for political or personal motives.”

Archbishop Taschereau judged it his duty to straighten things out. In his pastoral letter of 24 May 1876, he stated that it was necessary to discriminate between the liberalism which had been condemned and the liberalism which had not. He enjoined his priests not to speak of politics in the pulpit or elsewhere, and to show no preference for any candidate. But Bishop Persico believed the archbishop could no longer control the situation. Rome would have to institute an inquiry on the spot: this would be the mission of Bishop George Conroy*.

Bishop Bourget thought that his resignation at this time would quell the storm. Such was his wish when on 28 April 1876 he asked Cardinal Franchi “to persuade the Holy Father, by accepting my resignation, that I be cast into the sea, so that perfect calm might be restored.” On 15 May he learned that his resignation had been accepted by the pope, to take effect in September.

Bourget was appointed archbishop of Martianopolis, the former capital of Moesia Inferior, a region that partly corresponds to present-day Bulgaria, and retired to the residence of Saint-Janvier de Sault-au-Récollet in the spring of 1877, together with his loyal secretary of more than 30 years, Abbé Joseph-Octave Paré*. Ill and exhausted, Bourget had, as he said many times, but one desire: to “meditate on the years of eternity.” Only twice did he come out of his seclusion for any substantial period. The first time, urged by the die-hard supporters of an independent university at Montreal, the old man, then nearly 82, embarked on yet another journey to Rome from 12 Aug. to 30 Oct. 1881. He was unsuccessful, for Propaganda confirmed its decree of 1 Feb. 1876: there would be only one Catholic university in the province of Quebec. The second time, to help pay off the diocese of Montreal’s enormous debt of some $840,000, he travelled through the parishes, in all seasons regardless of the weather, to collect donations. In his memorandum to the clergy on 11 Oct. 1882 he announced that his trip had yielded the grand total of $84,782. This sum was no more than a tenth of the amount necessary to extinguish the debt but, in the words of one of his friends, “he re-established the confidence which seemed temporarily to have ebbed in the possibility of meeting the diocese’s monetary crisis.” On 9 Nov. 1882, at Boucherville, concluding his diocesan collection he celebrated the diamond anniversary of his ordination.

This occasion really was the end of his public life. Sick and growing ever weaker, he passed away on 8 June 1885. After an impressive funeral in the church of Notre-Dame, his body was placed in a vault of the unfinished cathedral in Montreal. A commemorative statue by artist Louis-Philippe Hébert*, a former Papal Zouave, has stood in the parvis of the building since 24 June 1903. His remains were finally transferred on 20 March 1933 to another part of the cathedral, the mortuary chapel for bishops and archbishops; his mausoleum, which stands in the centre, is the visual symbol of his pre-eminent place in the history of the diocese.

Even today the personality and work of the second bishop of Montreal still inspire intense feelings. One has only to look through recent historical works to realize that there are fewer devotees than there were 10 or 20 years ago, and that his religious and political conceptions are being scrutinized more and more critically. It is impossible to think of Ignace Bourget as other than a man of the church, but it was an authoritarian, uncompromising, intolerant church, in short the church of the last phase of the pontificate of Pius IX, whose anathema against the modern world in the end confined Roman Catholics as a body to a kind of ghetto. On the other hand, to do justice to the bishop, one must stress the tireless worker he proved to be despite an often deplorable state of health; the leader who awakened the devotion of so many; the man of prayer whose saintliness inspired a veritable cult; and finally the effective administrator who set up or helped to set up so many lasting institutions within and beyond his diocese. That is why Bishop Bourget remains, despite his inadequacies, one of the great architects of the province of Quebec.

[The ACAM is of course the principal source for information on the life and work of Bishop Ignace Bourget. In particular, the Registres des lettres de Mgr Bourget (RLB) and the valuable file on the Institut Canadien (901.133; 901.134; 901.135) were used. In 1965, when the file was first opened, its contents had not yet been classified. A perusal of the file revealed that there was a wealth of information in the material from the institute’s members or about them; in particular, the numerous letters from Louis-Antoine Dessaulles to Bourget on the difficulties arising between the institute and the bishop proved most important and useful for defining the existing liberal and ultramontane ideologies and delineating the conflict between lay and clerical forces at that time.

The Mandements, diocèse de Montréal, I–VIII, are an essential printed primary source. The most complete list of Bourget’s writings is to be found in Léopold Beaudoin’s thesis, “Bio-bibliographie de Monseigneur Ignace Bourget” (thèse de Bibliothéconomie, univ. de Montréal, 1950). Danielle Boisvert’s recent work, Inventaire sommaire d’une collection de mandements, lettres pastorales et circulaires de Mgr Ignace Bourget (P 66), 1840–1858 (Montréal, 1979), prepared as one of the publications of AUM, is also useful.

Father Léon Pouliot spent more than 40 years studying the life and work of Bishop Bourget. He published numerous studies in various reviews and periodicals, and then synthesized these in his principal work: Monseigneur Bourget et son temps (5v., Montréal, 1955–77). He also wrote Les dernières années (1876–1885) et la survie de Mgr Bourget (Montréal, 1960). Anyone who writes on Bourget is inevitably indebted to this remarkable accumulation of information on the second bishop of Montreal. Volume IX of Arthur Savaète’s major study of ecclesiastical matters in Canada, Voix canadiennes, vers l’abîme (12v., Paris, 1908–22), also proved useful. In addition to Lucien Lemieux’s fine scholarly and detailed history of the diocese of Montreal, L’Établissement de la première province ecclésiastique au Canada, 1783–1844 (Montréal et Paris, 1968), the following works were used: Serge Gagnon, “Le diocèse de Montréal durant les années 1860,”Le Laïc dans l’Église canadienne-française de 1830 à nos jours (Montréal, 1972), 113–27; René Hardy, “Les zouaves pontificaux et la diffusion de l’ultramontanisme au Canada français, 1860–1870 (thèse de phd, univ. Laval, Québec, 1978); Robert Perin, “Bourget and the dream of a free church in Quebec, 1862–1878” (phd thesis, Univ. of Ottawa, 1975); and Sylvain, “Libéralisme et ultramontanisme.” Unfortunately it has not been possible to consult the phd thesis which Mme Huguette Lapointe-Roy is currently preparing at Université Laval on various aspects of the social history of mid-19th-century Montreal. p.s.]

Cite This Article

Philippe Sylvain, “BOURGET, IGNACE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourget_ignace_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourget_ignace_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Philippe Sylvain |

| Title of Article: | BOURGET, IGNACE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |