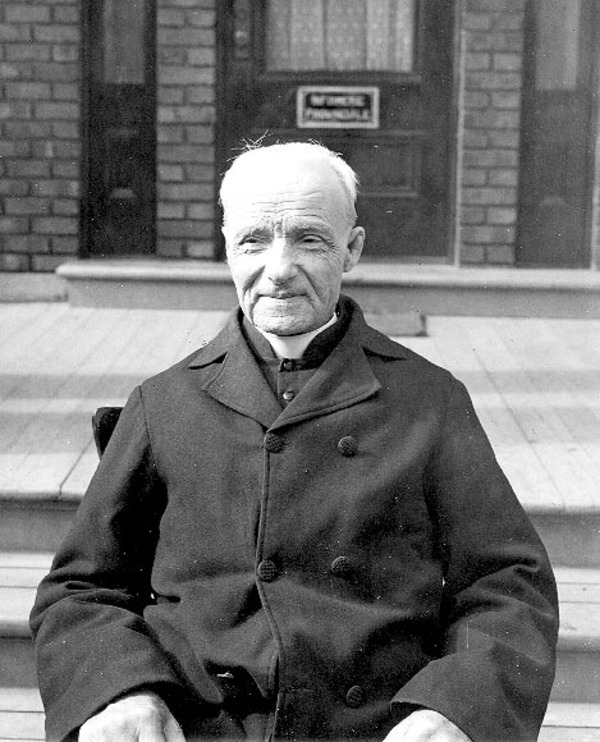

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

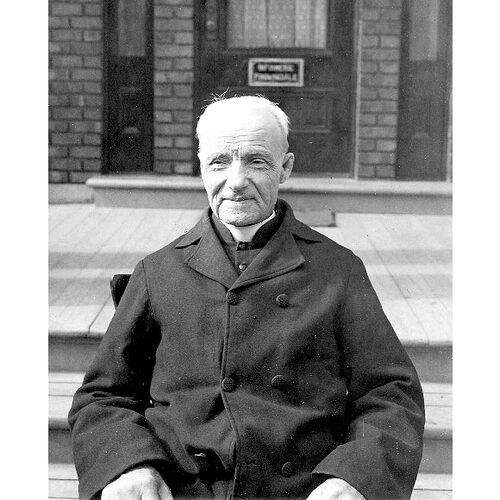

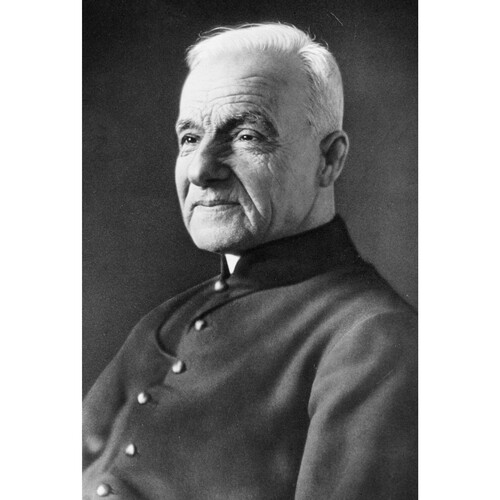

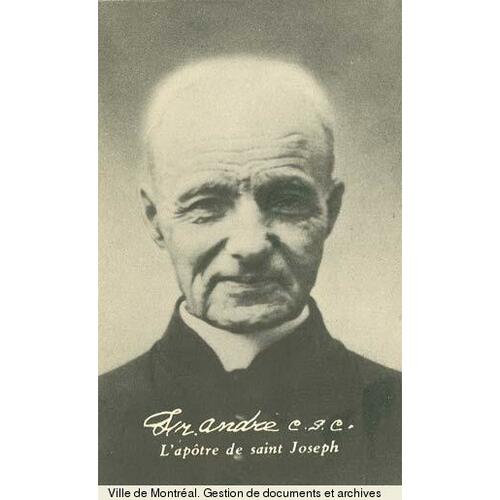

BESSETTE, ALFRED, named Brother André, lay brother of the Congregation of Holy Cross and charismatic figure; b. 9 Aug. 1845 in the parish of Saint-Grégoire (Mont-Saint-Grégoire), Lower Canada, son of Isaac Bessette and Clothilde Foisy; d. 6 Jan. 1937 in Notre-Dame-de-l’Espérance hospital in Ville Saint-Laurent (Montreal).

Alfred Bessette was the ninth of 13 children (four of whom died in infancy). He was so frail when he was born that the curé baptized him “conditionally” the following day, completing an emergency ritual performed at his birth. In the fall of 1849 Isaac Bessette sold his property in Saint-Grégoire and bought a parcel of land nine miles to the southeast, in Farnham, near the Rivière Yamaska. As the father of a family living in poverty, he worked at various trades: joiner, carpenter, cooper, cartwright. On 20 Feb. 1855 a tree he was chopping down fell on his chest and killed him. Left alone with her children, Clothilde made sure they had a Christian education and passed on to them the traditional veneration of the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. Still suffering from the shock of her husband’s death, she wasted away and died of tuberculosis on 20 Nov. 1857.

Alfred was 12 years old. He was taken in by his maternal aunt Marie-Rosalie and her husband, Timothée Nadeau, who lived in Saint-Césaire. He took lessons in catechism, and was confirmed by the first bishop of Saint-Hyacinthe, Jean-Charles Prince*, on 7 June 1858. Because of his poverty and delicate health, his studies were cut short; he would only be able to sign his name and read printed characters. To earn a living, Alfred worked at transporting construction materials. When his uncle Timothée set out for California in search of gold in 1860, the mayor of Saint-Césaire, Louis Ouimet, took the youth in to work on his farm. After that, Alfred engaged in various trades in Farnham, Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu), Waterloo, and Chambly. In 1862 he was back in Saint-Césaire, employed as an apprentice baker and cobbler. This wide variety of work experiences did nothing to improve his condition. According to witnesses, he could not digest anything, but he was always praying. Since his early childhood in Farnham, Alfred’s behaviour had worried his acquaintances. In spite of his weak condition, he denied himself dessert and he wore a leather belt studded with iron points around his waist. He would kneel in prayer frequently, intensely, and for long periods at a time; he could be found with his arms stretched out at his sides, in front of a crucifix, at church, in his room, or in a barn.

Hoping to find work fitting his constitution, Alfred took the train to New England in October 1863. Thousands of his compatriots, attracted by its prosperity, had gone there already, including some of his brothers, sisters, and acquaintances. The young 18-year-old, who found factory work almost more than he could bear, shifted between jobs in cotton mills and work on farms. He was hired in Connecticut (Moosup, Putnam, Hartford, and Killingly), Massachusetts (North Easton), and Rhode Island (Phenix). Alfred was reserved by nature and, worn out after a day’s work, would shut himself up in his room and pray.

After looking for suitable work for four years without success, Bessette returned to Canada in 1867 and settled in Sutton, where his sister Léocadie and his brother Claude lived. He soon went back to Farnham, where the local priest, Édouard Springer, hired him to take care of his horse and garden and do difficult chores around the presbytery. When Springer moved to another parish in 1868, Bessette went back to live at the home of Louis Ouimet in Saint-Césaire. Noticing his piety, Ouimet mentioned it to his curé, André Provençal. When questioned about his desire to enter the religious life, Alfred pleaded that he was too ignorant. Abbé Provençal overcame his reluctance by assuring him that he would find the prayerful environment he needed and useful work in the Congregation of Holy Cross, which the priest had put in charge of a school in his parish in 1869.

On 22 Nov. 1870 Bessette showed up at the Collège Notre-Dame, in Côte-des-Neiges (Montreal), where the Congregation of Holy Cross had recently opened its noviciate. Provençal had written a letter of recommendation the previous month to the master of novices, Julien-Pierre Gastineau, telling him that he was sending a saint to his community. On 8 December Pope Pius IX declared St Joseph to be the patron saint of the universal church. On 27 December Bessette took the name of André, in honour of Father Provençal, and he and another postulant donned the religious habit. He was appointed the school’s doorman, a position he would hold until mid July 1909. He also had to keep the premises clean, do the shopping, and give alms to the poor. In addition, he acted as barber and as nurse to sick students, handled the mail, and transported parcels for the students, whom he sometimes accompanied on the days when they went on outings. The congregation’s superiors hesitated, however, to accept him into the religious life in 1872 because of his poor health. When Bessette had a conversation with Bishop Ignace Bourget*, who had himself brought the congregation to Canada [see Joseph-Pierre Rézé*; Jean-Baptiste Saint-Germain*], he was reassured. Soon afterwards, the new master of novices, Amédée Guy, recommended him by saying: “If this young man becomes unable to work, he will at least be able to pray well.” Permitted to take his temporary vows on 22 Aug. 1872, Brother André made his final vows on 2 Feb. 1874, at the age of 28 years and six months.

Some of the visitors whom Brother André, as doorman, welcomed at the school asked him to pray for them in their illnesses. Others invited him to visit them at home. He would pray with them, and give them a medal of St Joseph, to whom he had early sworn a particular veneration, as well as a few drops of the olive oil that was burning before the saint’s statue in the school chapel, advising them to rub it on themselves confidently. More and more people began declaring that they had been entirely or partly cured in this way. The first known account, written by Désiré-Michel Giraudeau, named Brother Aldéric, who reported his own cure as well as that of several others, was published in Paris in 1878 in the Annales of the Association de Saint-Joseph. The little brother’s reputation – he was barely five feet tall – as a saintly miracle worker spread by word of mouth. The school authorities eventually began to worry about the growing flood of visitors. Parents, colleagues, and even the school physician complained to the town’s religious and health authorities about the presence of sick people so close to the students. Some called Brother André a charlatan, a mere anointer. Around 1900 he was asked to see the sick in a shelter that had been built across from the school, at the streetcar stop, for the students’ parents. He took his visitors to pray before a statue of St Joseph that he had set up in a niche on Mount Royal. The land, which had been purchased in 1896 by the Collège Notre-Dame, was named Parc Saint-Joseph; the lower part was cultivated and the upper part was used for recreational purposes. Brother André’s cherished project was to build a chapel to St Joseph there. With the support of his friends – a number of whom had had their wishes granted after praying with him – he finally obtained permission to build it. The school authorities and Archbishop Paul Bruchési of Montreal stipulated, however, that any expenses incurred should be borne by those seeking help. Thanks to spontaneous donations in cash and in kind (for example, statues, vases, liturgical vestments, a bell), the rudimentary sanctuary was inaugurated on 16 Oct. 1904.

From 1905 to 1908 the celebration of Ascension Thursday and a September procession marked the opening and closing of the pilgrimage season. After meeting a number of times in 1907, the zealous supporters of St Joseph’s Oratory constituted themselves a committee on 9 Sept. 1908, naming it the Comité de l’Oratoire Saint-Joseph de la Côte-des-Neiges. The flood of pilgrims was so great that the chapel would have to be enlarged four times between 1908 and 1912. Each time, the generosity of the public would make it possible to pay for the work in full and on time. The committee remained in existence until mid July 1909, when the authorities of the Collège Notre-Dame took over the administration of the oratory, with Brother André as its custodian. A religious association, the Confrérie de Saint-Joseph du Mont-Royal, was officially constituted by Archbishop Bruchési on 21 Nov. 1909, and it included laity, both men and women, friends of Brother André, and contributors to St Joseph’s Oratory and its works. They were convened by the rector of the oratory, provincial superior Georges-Auguste Dion*, for an hour of prayer on the third Sunday of every month at 3:00 p.m. This was the occasion for reporting on the affairs of the sanctuary: letters received, requests for prayers or masses, cures, various small items about the development and activities of the oratory. By 1910 Brother André had a secretary to answer the mail addressed to him.

In 1912 the board of St Joseph’s Oratory was organized; it consisted of three priests and three Holy Cross brothers, including Brother André. The monthly magazine Annales de Saint-Joseph began publication in Montreal that same year. Its purpose was to promote the veneration of St Joseph, publicize the work of the oratory and the missions of the Congregation of Holy Cross in Bengal, and comment on the social concerns of the day. An English edition would come out in 1927. A team of brothers and priests wrote articles and columns; a group of selected authors, such as Félix Leclerc*, Guy Mauffette*, Alfred DesRochers*, Françoise Gaudet-Smet [Gaudet*], and Marie-Antoinette Grégoire-Coupal, as well as the illustrators Edmond-Joseph Massicotte*, Jacques Gagnier*, and Gui Laflamme, would add their contributions later. The magazine was still being published in the early 21st century under the name L’Oratoire. From 3,600 in 1912, the circulation would grow to 122,000 in 1932.

There was a growing stream of visitors to the sanctuary. In 1913, under pressure from lay people and with the encouragement of Archbishop Bruchési, a proposal for a basilica was set in motion, with plans drawn up by architects Louis-Alphonse Venne and Dalbé Viau. The funds needed to finance the construction of the crypt, some $80,000, had already been raised through donations from the faithful. Construction began in 1914, and the crypt – the first stage of the project – was inaugurated on 16 Dec. 1917, but less than a year later the sanctuary, which could seat 1,000, proved too small. The number of visitors continued to increase throughout the 1920s, during which time, in accordance with the wishes of the archbishop and his coadjutor, Bishop Georges Gauthier, the sanctuary became the centre of the religious activities of the archdiocese. Associations of every kind – social movements, Catholic trade unions, religious confraternities – got into the habit of making pilgrimages and holding gatherings there, which drew thousands of people. Annual visits to the oratory were organized in parishes and educational institutions.

Visitors came not only from Quebec, but also from Ontario, New Brunswick, western Canada, and the United States. Brother André received them every day from 9:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. In the evenings, friends drove him to the homes of people who were too ill to travel. Since one person alone could not answer the 200 or 300 letters he received daily, a secretariat was set up. In 1920 Brother André instituted the observance of a holy hour in the crypt on Fridays at 8:00 p.m., which soon came to be followed by a visit to the stations of the cross. The faithful came by the hundreds to these evenings of prayer. The idea of atonement, put forward by the religious authorities to counter the threat of socialism and communism as well as the wars in Europe, gave rise to various lay initiatives. Beginning in 1926, for example, Édouard-L.-H. Barsalo organized a pilgrimage on foot to attend the first mass of the year at the oratory; hundreds, and then thousands of people answered the call.

By 1915 Brother André’s superiors were letting him take a short rest twice a year. He used the time to visit relatives and friends in Sutton, Saint-Césaire, and Quebec City, but also in the United States (especially New England) and in Ontario (Toronto, Sudbury, and Ottawa). His reputation as a saint and miracle worker preceded him. Stationmasters announced his arrival and crowds gathered as he got off the train and at the doors of the hotels or presbyteries where he was staying. Each time, cases of healing were reported in the local newspapers. He always came back with offerings given in gratitude for favours received. There was a growing popular demand that the plan for a basilica be acted on, and in 1927 Gauthier authorized a financial campaign to raise the necessary funds. Meanwhile, work continued on developing the land, building roads and parking lots, and providing service facilities.

The wonders that were worked at St Joseph’s Oratory drew the attention of the press, especially the English-language papers. In 1922 George Henry Ham*, a lobbyist for the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, published in the Toronto magazine Maclean’s a report he had written after visiting Brother André and meeting people whom he was said to have healed. The article aroused so much interest that Ham immediately followed it by publishing in Toronto the first biography of Brother André, The miracle man of Montreal, which was translated at once by Raoul Clouthier and published in Montreal as Le thaumaturge de Montréal. In the same year, Arthur Saint-Pierre* was commissioned to write the history of the sanctuary; L’oratoire Saint-Joseph du Mont-Royal, which came out in Montreal, would go through numerous editions.

After showing a great deal of reluctance towards his project of a shrine, Brother André’s superiors were finally won over by the sincerity, simplicity, and conviction of the man who based his cause, not on any claim to miracles or visions, but only on his veneration for St Joseph. To this special devotion were added the love of God, constant reading of the Gospel, and worship of the Holy Family and the Sacred Heart. He used to tell the story of the Passion of Christ to his intimate friends with such emotion that they were moved and transformed by it. He prayed and walked the stations of the cross with them. He asked them all to pray. Among those who accompanied him diligently were Jules-Aimé Maucotel, whom he called his counsellor and who actively assisted in organizing ceremonies; Azarias Claude, a wealthy merchant who became his right hand and chauffeur; and Joseph-Olivier Pichette, who at 25 had been told by his physician that he would soon die, and who attributed his recovery to long prayers with the miracle worker.

Years before his death, Brother André was already the symbolic figure of St Joseph’s Oratory. His charisma, his smiling face, wrinkled and radiating kindness, and his simple humour could win over even the most indifferent. He showed good judgement with his visitors, but also boundless charity; he welcomed everyone who came, regardless of social condition or religion. Although he liked to laugh, he also had moments of impatience, especially when someone gave him the credit for favours received. “It is not I who heals,” he would say, in tears. “It is St Joseph.”

Alfred Bessette died on 6 Jan. 1937. His body lay in state in the oratory – which was kept open day and night – until 12 January. An initial funeral service was held in the cathedral in Montreal, and a second one at St Joseph’s Oratory. More than a million people came from all over to pay tribute to him, to weep for him, and to pray beside him. Brother André was beatified by Pope John Paul II on 23 May 1982 and canonized by Pope Benedict XVI on 17 Oct. 2010.

The most complete bibliography for Brother André can be found in Étienne Catta, Le frère André (1845–1937) et l’oratoire Saint-Joseph du Mont-Royal (Montréal et Paris, 1965). Denise Robillard, Les merveilles de l’oratoire: l’oratoire Saint-Joseph du Mont-Royal, 1904-2004 (Montréal, 2005), updates Catta’s work by adding the titles which have appeared in the last 40 years. For supplementary information the reader should consult Laurent Boucher, Brother André: the miracle man of Mount Royal (Montreal, 1997).

BANQ-CAM, CE604-S11, 10 août 1845. Le Devoir, 7 janv. 1937.

Cite This Article

Denise Robillard, “BESSETTE, ALFRED, named Brother André,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bessette_alfred_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bessette_alfred_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Denise Robillard |

| Title of Article: | BESSETTE, ALFRED, named Brother André |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |