Source: Link

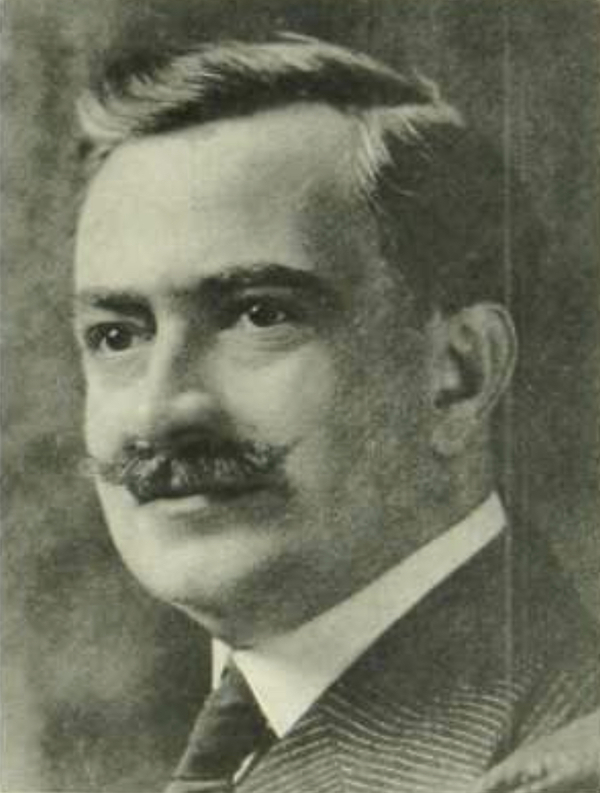

VENNE, LOUIS-ALPHONSE (he also signed Alphonse), architect, teacher, and politician; b. 24 Aug. 1875 in the parish of Notre-Dame, Montreal, son of Alphonse Venne, a carter, and Marguerite Patenaude; m. there on 26 June 1900 Louisia Moll, and they had at least two sons and four daughters; d. 16 Jan. 1934, probably in Saint-Lambert, Que., and was buried three days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery, Montreal.

Louis-Alphonse Venne spent his childhood in the western suburbs of Montreal. He attended educational institutions run by the Brothers of the Christian Schools, including the École Sainte-Cunégonde, where he received his secondary-school diploma. This religious community was renowned at the time for its teaching of the sciences and the arts, especially drawing. Venne passed the matriculation examination of the Province of Quebec Association of Architects in July 1895 and then became an intern with the large Montreal architectural partnership of Maurice Perrault*, Albert Mesnard, and Joseph Venne*. He also took courses at the school of the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec. As a result, he did not have to sit the association’s official exam. In 1898 he obtained a licence to practise.

From 1898 to 1909 Venne was employed by Perrault’s firm, which from 1895 had only one principal and no partners. He worked there as a draftsman, which meant that he did not sign his drawings or pay dues to the PQAA. He attracted attention in 1901 when he presented a design for a commercial building at the first exhibition of the Toronto Architectural Eighteen Club. From 1903 he also took on some contracts in his own name. After his marriage he lived near his wife’s family in Saint-Lambert, a new suburb linked to Montreal by the Victoria Bridge. He would be a municipal councillor there from 1911 to 1914 and then mayor in 1915 and 1916, while continuing to work as an architect in Montreal. He supervised the construction of several residences in Saint-Lambert – including his own – and in Montreal. At Würtele-Moreau-et-Gravel (Ferme-Neuve) and in the Montreal parish of Saint-Denis, he provided the plans for temporary churches. These were modest structures that could be replaced by stone or brick buildings when parish finances permitted. Venne also took on repairs to commercial establishments such as the warehouse of B. Ledoux and Company in Montreal, and the creation of the presbytery, the town hall, and the convent of Saint-Lambert. When Perrault died in 1909, Venne took over his clients. He worked on, among other things, two large projects begun by his employer: the restoration of the cathedral in Saint-Hyacinthe, and the construction of the Montreal Technical School [see John Smith Archibald]. He also taught draftsmanship at the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec from 1902 to 1909 and again from 1910 to 1912.

Venne gained a higher professional profile from 1910 when he won an architectural competition to design some of the triumphal arches for the International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal. The following year he advertised himself in Canada ecclésiastique (Montreal) as “the prize-winning architect of the arches and decorations of the eucharistic congress on the streets of St‑Hubert, Laval, and Rachel.” In particular, the competition gave him the opportunity to meet Canon Georges-Marie Le Pailleur, the curé of the parish of Saint-Enfant-Jésus in Montreal, who introduced him to an architect he favoured, Dalbé Viau. Moreover, Le Pailleur got them their first joint commission: creating the new headquarters of the French Canadian Artisans’ Society of the City of Montreal. In 1911 Venne was awarded fourth prize in the competition for building the Bibliothèque Saint-Sulpice.

Viau and Venne formalized their partnership in 1912 under the name Viau et Venne. Their relationship with the senior clergy in the diocese of Saint-Hyacinthe and the archdiocese of Montreal, including Canon Le Pailleur, enabled them to secure several contracts for religious buildings. New parishes were established in the working-class quarters of Montreal and churches had to be erected for the many faithful; as a result, the religious architecture of the Montreal firm of Viau et Venne would be essentially urban. In the new parishes, which were densely populated in comparison to rural districts and therefore had considerable means at their disposal, the architects were able to create large, prestigious churches. They provided the plans for the church and presbytery built in 1913 in the parish of Saint-Anselme and for those put up in the parish of Notre-Dame-du-Saint-Rosaire (1928–29). They built the church of Saint-Athanase in Iberville (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu) (1912–14), the church of Sainte-Cécile in Trois-Rivières (1913–14), and the cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Fourvières in Mont-Laurier (1917–19). In 1922 they restored the church of Saint-Denis (in Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu). As well, the two architects repaired buildings damaged by fire, notably the Montreal church of Saint-Stanislas-de-Kostka in 1918 for which Venne had also furnished the original drawings in 1911, followed by the church of Saints-Anges-Gardiens de Lachine (Montreal) in 1918, and the church of La Nativité-de-la-Sainte-Vierge d’Hochelaga (Montreal) in 1922–23.

In the domain of religious architecture, the firm’s most important work remains St Joseph’s Oratory [see Alfred Bessette]. It was one of a group of large religious edifices constructed on a mountainside and likely to inspire pilgrimages, a trend begun in Europe at the end of the 19th century. Erected on the north slope of Mount Royal, the oratory comprised a base, the crypt, intended for religious activities, and an upper section clad in architectural elements that were visible from afar. Built largely of stone in the Renaissance style, it was reminiscent of Santa Maria del Fiore cathedral in Florence. The architects delivered the plans in 1914. The initial construction was carried out during the 1920s, but the economic crisis of the 1930s had a negative impact on the internal financing of the project. Work resumed in 1937, notably to position the dome, for which a new design had been provided by the French architect Paul Bellot. With this change the Congregation of Holy Cross, which was in charge of administering the oratory, showed a preference for a less ornate architectural style. Some inspectors, furthermore, doubted that the dome designed by Viau et Venne could be safely built. Nevertheless, the oratory overall seemed harmonious and, for the rest, it generally respected the original plans of the Montreal architects.

In Canada ecclésiastique of 1911 Venne described himself, justifiably, as a specialist in religious and educational edifices. In fact he built a number of schools, convents, and colleges, for some of which Viau had signed contracts before their partnership was formed. With the great increase in population, improved funding for school boards, the influence of religious communities, and the introduction of specific building codes, there was no shortage of commissions for several Montreal architectural firms, including that of Viau and Venne. Among other contracts, it secured those for the Collège Saint-Romuald in Farnham (1913–14), the École Lajoie in Outremont ( Montreal) and the Académie Laurier in Montréal (1914), Mont-de-La-Salle in Laval-des-Rapides (Laval) (1915–17), and the Académie Saint-Viateur in Joliette (1918–19). Although civic architecture was not a major part of Venne and Viau’s work, a few such projects were placed in their hands: the fire hall and the police station on Avenue Boyce (Avenue Pierre-De Coubertin) in Montreal, and the town hall in Lachine.

At the time Venne was in practice, North American architects sought to apply European craftsmanship to their buildings and, depending on the sums at their disposal, reverted to nearly all the conventions of past centuries. Viau and Venne, for example, stayed within their estimates when drawing up plans for educational institutions; a measure of creativity was reserved for the exterior and was subject to budgetary constraints. Ornamentation was concentrated on the facade, around the main entrance and the windows, and was reminiscent of the motifs used in classical architecture of beaux-arts inspiration. The partners also attempted to give their work a distinctive character by using materials of different sizes and colours. Like other architects of their generation, Viau and Venne had a style that was neither inventive nor spectacular. They kept within estimates, took no risks, and did an honest job.

In the 1920s Venne and Viau were at the height of their careers. They executed major commissions from Montreal religious communities, often obtained through connections or family ties. They built the largest convent of the time, the mother house of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary in Outremont (1923–25). They supplied plans for the new building of the Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur in Montreal (1924–25), which was directed by the Sisters of Charity of Providence. In the same city and in the same style, they built the Bourget wing of the Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu (1926–28), which also belonged to the Sisters of Charity of Providence, and in 1927–28, in collaboration with the architect Alphonse Piché, the Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf, run by the Society of Jesus.

Louis-Alphonse Venne was the heir to Perrault, a renowned Montreal architect of the late 19th century. He held a prominent place in the firm that he founded with Viau; his achievements before their partnership substantiate his pre-eminence. Like Viau, Venne belongs to the small group of architects who left a mark on the work of their time, an era largely dominated by Catholic religious institutions. Their structures were solid, adapted to needs, and built according to the original specifications. Moreover, in form, their edifices were consonant with international architectural creations, and they rendered the beaux-arts style with the utmost efficiency and elegance. Venne et Viau produced imposing buildings that shaped the landscape. The rival Montreal firm of Louis-Zéphirin Gauthier* and Joseph-Égilde-Césaire Daoust had never achieved the same success.

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S51, 24 août 1875. FD, Notre-Dame (Montréal), 26 juin 1900. La Presse, 5 nov. 1913, 23 juill. 1914, 17 janv. 1934. Le Prix courant (Montréal), 1906–18. BCF, 1920. Directory, Montreal, 1892–1938. Raymonde Gauthier, Construire une église au Québec: l’architecture religieuse avant 1939 (Montréal, 1994); La tradition en architecture québécoise: le XXe siècle (Québec, 1989). André Laberge, “Transcender le style et la fonction: l’architecture religieuse de Viau et Venne (1898–1938)” (thèse de phd, univ. Laval, Québec, 1990). Montreal metropolis, 1880–1930, ed. Isabelle Gournay and France Vanlaethem (Toronto, 1998). Montreal Urban Community, Planning Dept. of the Territory, Architecture civile (2v., Montréal, 1980–81), 1 (Les édifices publics); 2 (Les édifices scolaires); Architecture religieuse (2v., Montréal, 1981–84), 1 (Les églises); 2 (Les couvents). Luc Noppen, Les églises du Québec (1600–1850) (Québec, 1977). Who’s who and why, 1917–21. Who’s who in Canada, 1922–29.

Cite This Article

Raymonde Gauthier, “VENNE, LOUIS-ALPHONSE (Alphonse),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/venne_louis_alphonse_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/venne_louis_alphonse_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Raymonde Gauthier |

| Title of Article: | VENNE, LOUIS-ALPHONSE (Alphonse) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2016 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | March 9, 2026 |