Source: Link

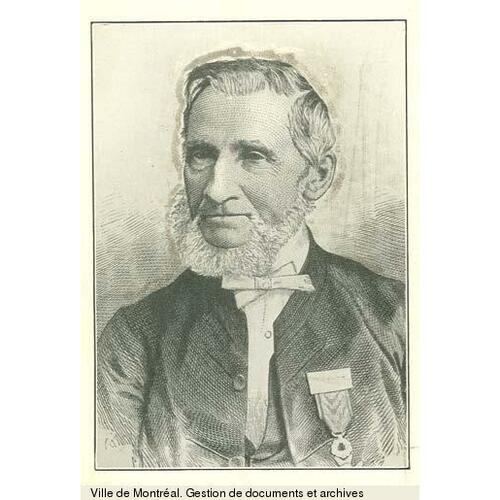

CHERRIER, CÔME-SÉRAPHIN, lawyer, politician, and businessman; b. 22 July 1798 at Repentigny, Lower Canada, son of Joseph-Marie Cherrier, a farmer and merchant, and Marie-Josephte Gaté; m. 18 Nov. 1833 in the parish of Notre-Dame in Montreal, Que., Mélanie Quesnel, widow of the merchant Michel Coursol, and they had four children; d. 10 April 1885 in Montreal and was buried there four days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Côme-Séraphin Cherrier belonged to the powerful network of the Viger, Papineau, Lartigue, and Dessaulles families. One of his father’s sisters had married Joseph Papineau*, the father of Louis-Joseph*, and another Denis Viger*, the father of Denis-Benjamin*. Following his mother’s death in 1801, Côme-Séraphin was brought up by the Viger family. After attending the Petit Séminaire de Montréal from 1806 to 1816, he studied law under Denis-Benjamin Viger and was called to the bar of Lower Canada on 23 Aug. 1822.

Cherrier practised law until the beginning of the 1860s. He retired at that time but according to contemporary accounts maintained his legal office on Rue Saint-Vincent as a private adviser. His first partnership was with Louis-Michel Viger*; later he worked with Denis-Aristide Laberge (1832–34) and Charles-Elzéar Mondelet* (1835–41), and then with Antoine-Aimé Dorion* (1842–60). One of Dorion’s brothers, Vincislas-Paul-Wilfrid Dorion*, joined the partnership in the early 1850s. In general, contemporary accounts agree on the importance of Cherrier’s legal career. He made his mark primarily in political trials. Following the 1827 elections the attorney general, James Stuart*, defeated by Wolfred Nelson* in the riding of William Henry, prosecuted a large number of voters for perjury. Stuart claimed they had falsely sworn that they met the property qualifications but Cherrier managed to disprove that there had been perjury. The following year, with his colleagues William Walker* and Dominique Mondelet*, he successfully defended the publisher and editor of the Canadian Spectator (Montreal), Jocelyn Waller*, who had been accused of libelling the administration of Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*]. On this occasion Cherrier demonstrated a thorough grasp of the finer points of a jury trial. In 1836 he offered his services to the residents of Saint-Benoît (Mirabel), who were charged with having cut off the tails and manes of several horses belonging to government officials. That year he defended Ludger Duvernay*, who had been indicted for his attack in La Minerve upon a report made by a grand jury of the Court of King’s Bench. At the time of the abolition of the seigneurial system [see Lewis Thomas Drummond] he argued one of the last of his famous cases. Chosen with Christopher Dunkin and Robert Mackay to represent the seigneurs and establish their claims for compensation, he drafted a detailed, elaborate speech (published in 1855) which earned him the warm thanks of the seigneurial commission. Finally, he was called upon to advise Bishop Ignace Bourget of Montreal in the quarrel over the division of the Montreal parish of Notre-Dame which developed between the bishop and the Sulpicians around 1866 [see Joseph-Alexandre Baile; Joseph Desautels].

The various honours and offices conferred upon Cherrier over the years testify to his fame. To recognize his assistance in 1851 in establishing a law course at the Collège Sainte-Marie [see François-Maximilien Bibaud], the Jesuits of St John’s University at Fordham, N.Y., awarded him an honorary lld in 1855. Having been the president of the library of the barristers’ society of Lower Canada for many years, in 1855 and 1856 he held the office of bâtonnier at the bar in Montreal. In addition, in 1877 he became titular professor and dean of the law faculty of the Montreal branch of the Université Laval of Quebec City.

His participation in political trials, as well, no doubt, as his family ties with the Montreal nucleus of the Patriote party, inevitably led Cherrier into politics. Yielding to pressure from his associates, according to his biographers, he ran in the riding of Montreal in 1834 and was elected to the assembly. He took part in the 1835 and 1836 sittings, but ill health prevented him from joining in the stormy debates prior to the 1837 rebellion. However, he did sometimes appear that year, and Fernand Ouellet without hesitation ranks him among the star performers of the Patriote party. In August 1837 he was one of the members of the house who disembarked at Quebec City dressed in clothes of local fabric, out of respect for the Patriote leaders’ instructions to wear no imported garments.

Although Cherrier’s speeches sought to further the struggle by constitutional means and were not the most violent to be delivered, he was nevertheless arrested and imprisoned on 1 Dec. 1837. His incarceration proved distressing; he fell seriously ill but was finally released to house-arrest in March 1838. Cherrier subsequently re-entered politics only once, in an unsuccessful bid for the mayoralty of Montreal in 1859 [see Charles-Séraphin Rodier*]. He turned down all other proposals, invariably for reasons of health: in 1842 when Sir Charles Bagot* offered him the post of solicitor general in order to conciliate French Canadians hostile to union, and again in 1844 when Denis-Benjamin Viger, to whom Cherrier owed a great deal, invited him to join the government. On three occasions he declined appointment to the bench, the final offer, in 1864, being that he should succeed Sir Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* as chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench of Canada East.

Although he withdrew from the political fore-stage after the rebellion Cherrier none the less continued to play an influential role. He belonged to the group of moderate Liberals, and through family ties was also in contact with the former Patriotes in Montreal, where in 1840 he participated in the first “anti-unionist” gathering. Subsequently, he seems to have supported La Fontaine’s alliances and plans for reform, at least on the evidence of their correspondence. Cherrier was likewise involved in the Association de la Délivrance, which bookseller Édouard-Raymond Fabre* set up in 1843 to facilitate the return of the political exiles. As one of Cherrier’s last political acts he gave a speech in 1865 to the Institut Canadien-Français against the confederation project. He cited four reasons for his opposition: the lack of consultation with the people; the surrender of local authority, in favour of a thinly disguised legislative union; the imminent danger of difficulties in the relations between provincial and federal governments; and the loss of taxation powers for Canada East.

By the mid 1850s Cherrier seemed to be a kind of sage, participating in the establishment of every organization, attending every meeting, and being consulted about everything. La Presse of Montreal on 10 April 1885 noted that “all the present generation had acquired the habit of seeing him wherever religious, patriotic or charitable endeavour was involved.” His reputation for wisdom stemmed at one and the same time from his moderation, his acknowledged legal erudition, his legendary indecisiveness, and, indeed, his obstinate refusal to make up his mind unequivocally. He was thus a complex individual, capable both of advising Bourget in his struggle against the Sulpicians and later of opposing his ultramontanism and also supporting his opponents at the Université Laval.

Cherrier became an active member of the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal upon its reorganization in 1843, and served as vice-president in 1852 and president in 1853. In 1860 he gave a remarkable address in defence of the temporal power of the papacy at Notre-Dame church in Montreal and hence in 1869 was proclaimed a knight of the Order of St Gregory the Great. This stand on behalf of the church no doubt brought him the favourable attention of the apostolic delegate Bishop George Conroy*; Cherrier wrote a letter to the bishop on 15 Sept. 1877 explaining the nuances differentiating the liberalism of French Canadians from the liberalism condemned by the Syllabus of 1864. Cherrier also belonged to the St Vincent de Paul Society of Montreal and was its vice-president for a time. His contribution to public charity was widely recognized and La Patrie of Montreal on 10 April 1885 even claimed that “the poor have lost in him a most tender father.” He was a member of the Council of Public Instruction in 1859 and again after 1867.

It is difficult to pin down the origin of Cherrier’s fortune, which at his death was valued by the Montreal Daily Star at more than $1,000,000. According to some of his biographers, his legal practice brought him a comfortable living, and in addition Denis-Benjamin Viger is thought to have made him a sizeable gift before 1844. Most of his landed property also came from Viger, who at his death in 1861 bequeathed to Cherrier all his personal chattels and real estate, including several properties in the Saint-Jacques district. Hence around 1870 Cherrier owned in this locality an area estimated at more than 770,000 square feet, as well as smaller lots in other districts of Montreal and on Île-Bizard, the seigneury which had belonged to Viger. Apart from his real estate Cherrier owned stock in a number of companies. During the 1840s, for example, he acquired (with George-Étienne Cartier*, George Moffatt*, and Alexandre-Maurice Delisle*) a block of shares in the St Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad Company. In 1865 he was listed as one of the 10 major shareholders of the Banque du Peuple, which he served as a director from 1865 to 1877 and as president from 1877 to his death. In the conduct of his affairs Cherrier apparently drew criticism for unwillingness to take risks with his property, which was left an undeveloped stretch in the urban landscape to the east of Rue Saint-Denis in Montreal. His biographers have excused him on the grounds that he lacked business sense, but no doubt his legendary indecisiveness was also a factor. Cherrier was, however, well aware that his land would inevitably increase in value and seems to have deliberately waited as long as possible. His occasional sales of property as well as certain other sources of revenue, for example the rent from the mill on Île-Bizard, enabled him to live comfortably in his residence on Rue Lagauchetière.

Wilfrid Laurier* has probably best described Cherrier’s complex and contradictory nature: “Côme-Séraphin Cherrier, one of the most eminent members of the bar of Lower Canada . . . , was himself a man of an exceptional kind. He scarcely belonged to our time, even to our continent. One would indeed have taken him for a living anachronism, for the incarnation of those remarkable figures who, at once powerful and affable, were the ornament of the parlement de Paris in the 17th century. A man of inflexible principles masked by an unfailing kind-heartedness, of liberal instincts restrained by conservative customs, of austere piety tempered by the most chivalrous spirit, he combined the most refined Attic wit with the simplicity of a child.”

Côme-Séraphin Cherrier was the author of Discours . . . prononcé dans l’église paroissiale de Montréal, le 26 février 1860, dans la grande démonstration des catholiques en faveur de Pie IX (Montréal, 1860); L’Honorable F.-A. Quesnel (Montréal, 1878); Mémoire . . . sur les questions soumises par l’honorable Lewis Thomas Drummond, procureur général de Sa Majesté pour le Bas-Canada, à la décision des juges de la Cour du banc de la reine et de la Cour supérieure, en vertu des dispositions de l’Acte seigneurial de 1854 (Montréal, 1855); Présidence des assemblées de fabrique de N.-D. de Montréal . . . ou réponse à la consultation de l’honorable procureur général Cartier, dans laquelle on prétend que le supérieur du séminaire de Montréal a ce droit de présider les assemblées de fabrique de la paroisse de Notre-Dame, à l’exclusion du curé de cette paroisse ([Lyon, France, 1866]); and contributed to Discours sur la confédération (Montréal, 1865).

ANQ-M, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Dame de Montréal, 18 nov. 1833; M-72-148; Minutiers, Joseph Belle, 22 oct. 1859; N.-B. Doucet, 12 déc. 1821; D.-É. Papineau, 16 nov. 1870, 27 juin 1873; Testaments, Reg. des testaments prouvés, 13, 7 oct. 1873. ANQ-Q, AP-G-43; AP-G-417. BNQ, mss-30; mss-101, Coll. La Fontaine (copies at PAC). PAC, MG 24, B46, 1. Extracts of the books of reference of the subdivisions of the city of Montreal, ed. L.-W. Sicotte (Montreal, 1874). Honoré Mercier, Feu Côme-Séraphin Cherrier: conférence faire à la salle de “La Patrie” . . . ([Montréal], 1885). Montreal Daily Star, 10 April 1885. La Patrie, 10 avril 1885. La Presse, 10 avril 1885. F.-J. Audet, Les députés de Montréal, 411–16. Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer, 257–58. Canadian biog. dict., II: 334–36. L.-O. David, Biographies et portraits (Montréal, 1876), 208–19. Dominion annual register, 1885: 252–53. Fauteux, Patriotes, 176–78. Montreal directory, 1842–85. R. S. Greenfield, “La Banque du Peuple, 1835–1871, and its failure, 1895” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1968), 4, 133–34. [Wilfrid Laurier], In memoriam: sir A.-A. Dorion, chevalier, juge-en-chef de la Cour d’appel, ancien ministre de la justice (Montréal, 1891). André Lavallée, Québec contre Montréal, la querelle universitaire, 1876–1891 (Montréal, 1974), 25–27, 54. Monet, Last cannon shot, 42, 100–1, 128, 146. Fernand Ouellet, Le Bas-Canada, 1791–1840: changements structuraux et crise (Ottawa, 1976), 441. Léon Pouliot, Mgr Bourget et son temps (5v., Montréal, 1955–77), V: 53. J.-L. Roy, Édouard-Raymond Fabre, libraire et patriote canadien (1799–1854): contre l’isolement et la sujétion (Montréal, 1974), 157–58. Robert Rumilly, Histoire de la Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal: des Patriotes au fleurdelisé, 1834–1948 (Montréal, 1975), 51, 54, 68.

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE601-S51, 14 avril 1885; CE605-S16, 23 juill. 1798.

Cite This Article

Jean-Claude Robert, “CHERRIER, CÔME-SÉRAPHIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cherrier_come_seraphin_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cherrier_come_seraphin_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Claude Robert |

| Title of Article: | CHERRIER, CÔME-SÉRAPHIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |