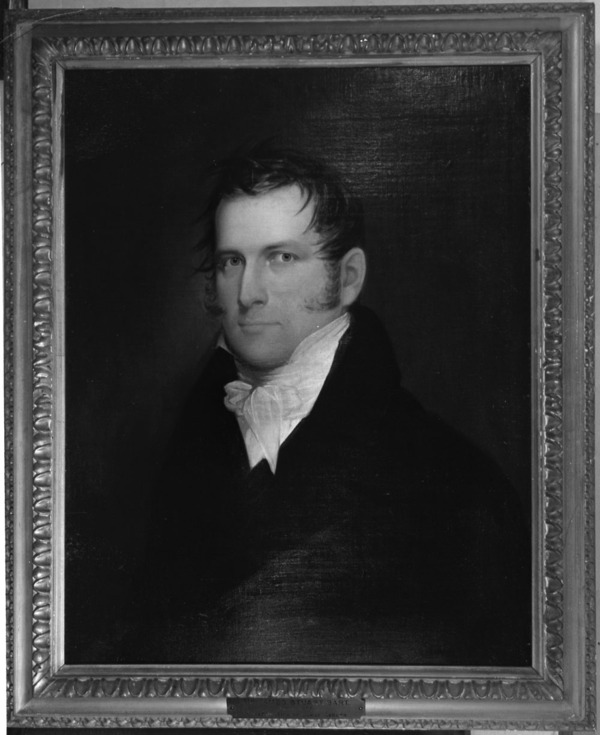

STUART, Sir JAMES, lawyer, office holder, politician, and judge; b. 2 March 1780 in Fort Hunter, N.Y., third son of the Reverend John Stuart* and Jane Okill; m. 14 March 1818 Elizabeth Robertson in Montreal, and they had three sons and a daughter; d. 14 July 1853 at Quebec.

A prominent member of the ruling élite of Lower Canada, James Stuart had pursued a career that was the logical outcome of his family background and his undoubted energy and talents. His father was not only a loyalist but also a respected Church of England clergyman, for many years the rector at Cataraqui (Kingston), Upper Canada. Despite some periods of financial difficulties, John Stuart took pains to ensure for his sons the best education available at the time to arm them against the possible influence of “the diabolical Principles of Equality” current south of the border.

James, a talented and precocious lad, completed his eminently conservative and Protestant schooling at King’s College, Windsor, N.S., and at the early age of 14 began his apprenticeship in the law in Lower Canada. After four years with John Reid, clerk of the Court of King’s Bench in Montreal, and two years at Quebec with Jonathan Sewell*, then attorney general, Stuart was called to the bar in the spring of 1801.

Favourably impressed with the young man, Sir Robert Shore Milnes*, the lieutenant governor, had already made Stuart his personal secretary. Although convinced that he could build a more flourishing practice in Montreal, Stuart filled this post in the hope of eventually obtaining a much better one from his patron – an expectation that was realized when he was made solicitor general on 1 Aug. 1805. Three years later he entered the House of Assembly as one of the two members for Montreal East. With his reputation in private practice growing apace at the same time, it is scarcely surprising that Stuart hoped to replace Sewell as attorney general when the latter was made chief justice of Lower Canada in September 1808. However, the new governor, Sir James Henry Craig*, named his own favourite, Edward Bowen*, to the post. As Bowen was less competent, Stuart, a man of arrogant and choleric temperament, confident of his own abilities and sensitive to slights, showed his resentment of Craig’s action. Craig later wrote to the Colonial Office that Stuart had neglected the social obligation of paying his respects to the governor, and, more seriously, although both a law officer and a member of the house, had not only neglected to ask the governor if he wanted any business introduced into the house but had also frequently voted with the “obnoxious party” against government measures. Stuart was to pay dearly for these snubs: in May 1809 Craig dismissed him from his post as solicitor general and replaced him with Stephen Sewell*, brother of the chief justice. Stuart’s bitterness over the dismissal was probably accentuated by his defeat in the elections of the following spring at the hands of Stephen Sewell.

Stuart harboured a fierce sense of grievance which appears, however, to have been focused primarily upon Jonathan Sewell. Elected for the riding of Montreal in a by-election in 1811, Stuart acquired the rather uncharacteristic role of leader of the Canadian party in the assembly, rallying it in a concerted attack on Sewell and his colleague James Monk*, chief justice of the Court of King’s Bench at Montreal. Stuart seized upon the recently promulgated rules of practice for the courts of King’s Bench at Montreal and Quebec and for the Court of Appeals, claiming that the judges had, by changing these rules, stepped outside the proper sphere of judicial activities, arbitrarily abrogating sections of the law and usurping the function of the legislature. On 27 Jan. 1813 he demanded an inquiry, with a view to impeaching the two chief justices. The assembly readily followed his lead and Stuart himself was the president of the special committee and author of the report it handed down in February 1814.

A close analysis of this report shows a mixture of ability and unscrupulousness characteristic of its author. A skilful lawyer, familiar with both the French and the English legal systems, Stuart pin-pointed a grave problem implicit in dispensing French civil law in British courts: judicial practice in a system of judge-made law was alien to the spirit underlying French civil law, and the judges were in fact usurping a function which, in the French legal system, belonged to the legislature. However, in a partisan spirit Stuart also threw in quite a few specious and tendentious arguments and couched the report in exaggerated and violent language that obscured the valid issues he raised and caused it to be dismissed by his contemporaries and later by historians such as Thomas Chapais* as a tissue of fabrications. Stuart’s lack of interest in solving the real problem he had raised is made clear by his refusal to acknowledge the judges’ good intentions or to propose a workable alternative. As Chapais has pointed out, when Stuart, as chief justice, revised the rules of practice in 1850, he maintained intact several of the very ones he had earlier attacked.

The “Heads of impeachment” against Sewell finally adopted by the assembly included, in addition to the specifically legal charges, a variety of charges of a political nature, accusing Sewell of subverting the constitution and introducing arbitrary and tyrannical government through his influence as Craig’s chief adviser. Stuart’s personal motives are particularly clear in the 7th clause of impeachment, which accused Sewell of causing the governor to “remove and dismiss divers loyal and deserving Subjects” because they were his political opponents and “in one instance, to procure the advancement of his brother.” Such disparate contemporary observers as Governor Sir George Prevost* and Pierre-Stanislas Bédard*, former leader of the Canadian party, agreed that in pressing such charges Stuart was motivated by “personal Animosity” and “works only for his own gratification.” Nevertheless, Stuart became one of the foremost leaders of the Canadian party from 1813 to 1817, during which time he relentlessly strove to keep the issue of the impeachment of the two chief justices alive.

The assembly’s charges, sent to England as an address to the Prince Regent, were submitted to the Privy Council. Sewell took a leave of absence to defend himself, and was spared a confrontation with Stuart in London by the Legislative Council’s refusal to vote funds to send Stuart over as the assembly’s agent. Not surprisingly, the Privy Council exonerated the two chief justices. When the assembly, led by Stuart, reacted early in 1816 to the news of the vindication of the judges with a series of resolutions complaining that it had been prevented from having its case fairly heard, the administrator of the colony, Sir Gordon Drummond, acting on instructions from the colonial secretary, dissolved the assembly and called an election.

Although Stuart revived the issue in the new parliament in 1817, the recently appointed governor, Sir John Coape Sherbrooke*, handled the rather explosive situation more adroitly than his predecessor. On receiving a petition from the assembly for a salary for its speaker, Louis-Joseph Papineau*, Sherbrooke agreed, provided that a similar salary be approved for the speaker of the Legislative Council (none other than Sewell himself). Determined to secure a salary for their leader, Papineau’s supporters voted as the governor had suggested. Stuart was absent at the time on business in Montreal. Subsequently, in spite of his most impressive and impassioned oratory, the assembly refused to support a motion reviving the impeachments. He never forgave his erstwhile followers for this betrayal and, in high dudgeon, he ceased to attend the assembly.

The 1820s were a decade of increasing conflict between the French Canadian majority in the assembly and the British merchants and bureaucrats in the councils. Stuart, now a strong supporter of British interests, played a notable role in these disputes. When the British party attempted to reunite the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada in 1822, he was a prominent speaker on behalf of union, and he was sent to London in February 1823 as the agent of the pro-unionists. He presented the officials of the Colonial Office with petitions in favour of union and also published a pamphlet entitled Observations on the proposed union of the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, under one legislature that ably and forcefully presented the case for union, stressing not only the obvious economic and geographic arguments but also the necessity of union for British predominance and the assimilation of the French Canadians.

Stuart used his sojourn in London to impress the Colonial Office with his own abilities. In the process, he produced a severe critique of the plan for a general legislative union of British North America proposed by Jonathan Sewell and John Beverley Robinson* and an analysis of the defects of the clause in the Canada Trade Act of 1822 relating to the conversion from seigneurial to freehold tenure. He succeeded in making a favourable impression on the colonial secretary, Lord Bathurst, who offered him the post of attorney general of Lower Canada, to which he was named on 31 Jan. 1825. The governor, Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*], called upon Stuart to run for election in order to represent the executive in the lower house. Stuart sat for the riding of William Henry from 1825 to 1827 and had the unenviable task of defending the Legislative Council’s measures in the house, where the Patriotes did not hesitate to point out the contradiction between his current and former positions. Papineau’s correspondence suggests that Stuart was frequently red with ill-suppressed rage and “overwhelmed with vexations and humiliations” by his former associates in the rough-and-tumble of assembly debates. In recognition of his valuable services, the governor named him to the Executive Council on 6 July 1827, a post he held until the union of the Canadas in 1841. Stuart contested his seat in the stormy election of 1827, but was narrowly defeated by Wolfred Nelson*.

Stuart continued to pursue the policies of the British party as attorney general. In 1828 he elaborated the government’s case against the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice, arguing that the seminary had no legal existence and hence no right to its property (most of Montreal Island), which, in his view, belonged to the crown. An opponent of seigneurial tenure and of the Lower Canadian laws applying to real estate, Stuart argued against a bill passed by the Legislative Council and the assembly in 1829 which attempted to eliminate the uncertainty caused by the Canada Tenures Act of 1825 as to the validity of titles in free and common socage that had been transferred or mortgaged by Lower Canadian law. Stuart deplored the “ill-defined inter-mixture” of English and French law that the bill allowed. In 1830 he also strongly advised the new governor, Lord Aylmer [Whitworth-Aylmer*], against granting a petition by Jean-Baptiste-René Hertel de Rouville for a new seigneury, arguing that such a concession would be contrary to the policy of gradual extinction of seigneurial tenure implicit in the Canada Tenures Act.

Stuart’s arrogance and his role as a pillar of the British party combined to make him the target of a series of accusations by the assembly culminating in a demand for his dismissal. In 1831 a committee on grievances collected evidence on four basic charges against the attorney general: encouraging the unnecessary issuing of new commissions to notaries upon the death of George IV in order to collect a fee for each one; prosecuting cases that should have been dealt with in inferior courts in superior ones, where fees were higher; abuses of his authority during the election of 1827; and conflict of interest in a case between William Lampson, lessee of part of the king’s posts, and the Hudson’s Bay Company, which had retained Stuart as a private attorney. Aylmer, though not necessarily agreeing with the assembly’s charges, felt that the delicate political situation in the province left him no choice but to suspend Stuart and to refer the accusations and the final decision to London. In this assessment Aylmer was correct: Papineau maintained that failure to suspend Stuart would be a clear sign that the governor was a servile tool of the British party. Stuart was suspended on 9 Sept. 1831 and was temporarily replaced by Charles Richard Ogden*.

Stuart was not a man to take suspension lightly. He challenged Aylmer to a duel (which Aylmer declined, with London’s approval), demanded compensation for the financial loss he was suffering, and prepared a voluminous defence against the assembly’s charges. He passed the next three years in London defending himself and then trying to obtain redress. The assembly had its agent in England, Denis-Benjamin Viger*, present its case. The evidence and arguments on both sides leave one uncertain as to Stuart’s guilt or innocence. Lord Goderich, the colonial secretary, eventually decided that, although some of the charges were absurd or unproven, others were not, and Stuart was dismissed in November 1832. This dismissal was not the result of a public trial and the counts on which Goderich considered Stuart guilty were not identical to the specific charges of the assembly. As a result, Stuart was able to appeal successfully to Goderich’s successor, Edward George Geoffrey Smith Stanley, on the grounds that his case had been dealt with unfairly. Unwilling to reverse Goderich’s decision, Stanley offered Stuart the chief justiceship of Newfoundland in recompense. Stuart refused and insisted on financial compensation, which neither Stanley nor his successor, Thomas Spring-Rice, was willing to concede. Angry and embittered, Stuart returned to his private practice in Lower Canada in 1834 without public exoneration or the satisfaction of his claim.

Stuart’s talents and energy had enabled him to build up a substantial private practice which included such well-known clients as Edward Ellice*, Lord Selkirk [Douglas*], and the HBC. In a manner typical of his time, he viewed private and public practice as complementary, and indeed, as his demands for financial compensation suggest, his income from public office was important to him. Evidence indicates that he was above all a practical lawyer, interested in the broader historical and philosophical aspects of the law only to the extent that they might occasionally further his personal goals.

Four years after his return fortune favoured Stuart. Sir John Colborne* named him to the Special Council on 2 April 1838. Stuart held the post briefly, for two months later Lord Durham [Lambton*] dismissed the council’s members and replaced them with his own appointees. However, Durham, finding in Stuart a man who shared his views, named him on 22 October as Jonathan Sewell’s successor when the chief justice retired. Durham justified the nomination on the grounds that Stuart was universally held to be “the ablest lawyer in the Province” and that his previous dismissal had been a “signal injustice,” the charges of the assembly having been the fruit of political animosity. After Durham’s departure he was once again appointed to the Special Council, on 11 Nov. 1839, serving as its president until a few weeks before its dissolution in February 1841. He was created a baronet on 5 May 1841.

As a member of the Special Council, Stuart voted in favour of the union of the Canadas, and Lord Sydenham [Thomson*] is said to have asked him to draft the legislation. He was also the author of the ordinance passed by the Special Council that established registry offices throughout Lower Canada, and thus put an end to a controversy which had lasted for decades. Among the consequences of this law was the virtual abolition of customary dower; not surprisingly, it was much resented by legal traditionalists such as François-Maximilien Bibaud* who saw in it an assault on the basic social values embodied in Lower Canadian civil law.

During the 1840s and 1850s Stuart was no longer the centre of controversy and he ended his life in the enjoyment of his honours and in the fulfilment of his obligations as chief justice of Lower Canada. All three of his sons succeeded to the baronetcy, which was extinguished by the death of the youngest in 1915.

An able and ambitious man, James Stuart was inevitably drawn into the political and ethnic conflicts that dominated the period. As a politician, with the exception of the interlude of his attack on Sewell, he was a supporter of the British party. As a jurist, he recognized the potential of the law as a means of assimilation, and he was at one with many of his British colleagues in striving to introduce more English law into the province. Although he was respected for his legal knowledge and talent, his personality was unendearing. Preoccupied with personal advancement, Stuart lacked both the attractive character and the diversity of interests that distinguished his brother Andrew* and the literary ability and statesmanlike breadth of vision shown by his long-time rival Jonathan Sewell.

James Stuart is the author of Observations on the proposed union of the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, under one legislature, respectfully submitted to his majesty’s government, by the agent of the petitioners for that measure (London, 1824) and of “Remarks on a plan, entitled ‘A plan for a general legislative union of the British provinces in North America’” which appeared in General union of all the British provinces of North America (London, 1824).

ANQ-Q, CE1-61, 24 juill. 1835, 16 juill. 1853. AO, MU 2923. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 109: 128–30; 188-2: 406–18; 195-2: 372; 198-1: 192; 210-1: 98–110; 212: 245; 220-2: 350, 356, 365, 377; 248-1: 159–62; MG 23, GII, 10, vo1.5: 2457–60, 2580–83; MG 24, B1; B2; B12; C3; L3: 7622–23, 31098–108 (copies); MG 30, D1, 28: 531–34; RG 7, G1, 25: 156, 159. L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1814, app.E; 1831, app.AA; 1831–32, app.A; 1836, app.EE. Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1791–1818 (Doughty and McArthur); 1819–1828 (Doughty and Story). Quebec Gazette, 22 Oct. 1822, 21 Dec. 1836. Quebec Mercury, 15 March 1814. F.-M. Bibaud, Le panthéon canadien (A. et V. Bibaud; 1891). DNB. Morgan, Bibliotheca Canadensis; Sketches of celebrated Canadians, 324–27. F.-J. Audet, Les juges en chef de la province de Québec, 1764–1924 (Québec, 1927), 59–66. A. H. Young, The Revd. John Stuart, D.D., U.E.L., of Kingston, U.C. and his family: a genealogical study (Kingston, Ont., [1920]). [F.-M. Bibaud], Commentaires sur les lois du Bas-Canada, ou conférences de l’école de droit liée au collège des RR. PP. jésuites suivis d’une notice historique (2v., Montréal, 1859–61). Buchanan, Bench and bar of L.C. Chapais, Cours d’hist. du Canada, vol.3. Evelyn Kolish, “Changement dans le droit privé au Québec et au Bas-Canada, entre 1760 et 1840: attitudes et réactions des contemporains” (thèse de phd, univ. de Montréal, 1980). J.-E. Roy, Hist. du notariat, 2: 459–73. G.-É. Giguère, “Les biens de Saint-Sulpice et ‘The Attorney General Stuart’s opinion respecting the Seminary of Montreal,’” RHAF, 24 (1970–71): 45–77.

Cite This Article

Evelyn Kolish, “STUART, Sir JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stuart_james_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stuart_james_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Evelyn Kolish |

| Title of Article: | STUART, Sir JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |