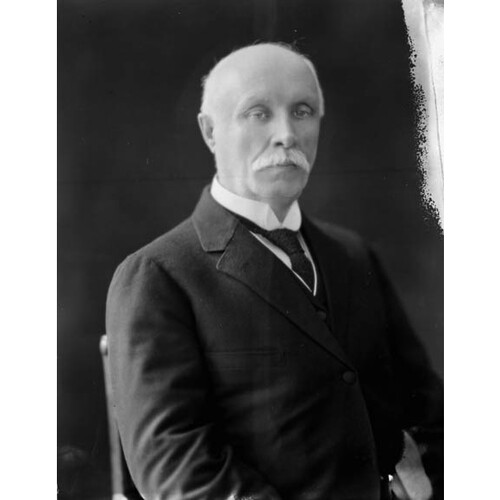

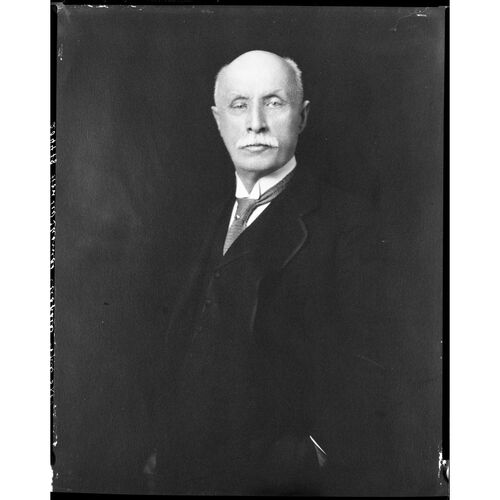

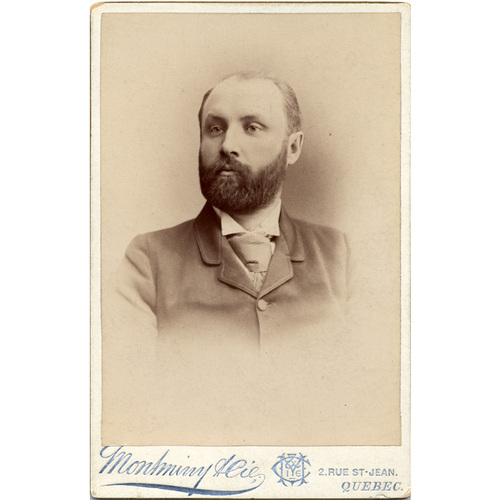

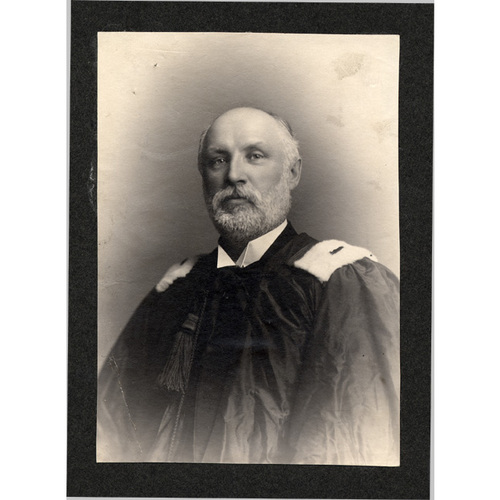

![Sir Thomas Chapais, [Vers 1887], BAnQ Québec, Collection Centre d'archives de Québec, (03Q,P1000,S4,D83,PC55-2), Montminy & Cie. Original title: Sir Thomas Chapais, [Vers 1887], BAnQ Québec, Collection Centre d'archives de Québec, (03Q,P1000,S4,D83,PC55-2), Montminy & Cie.](/bioimages/w600.15527.jpg)

Source: Link

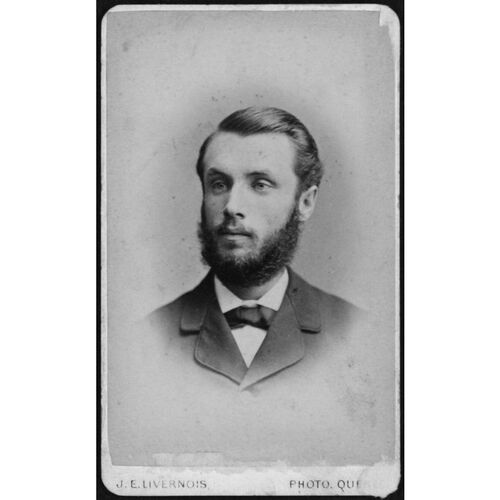

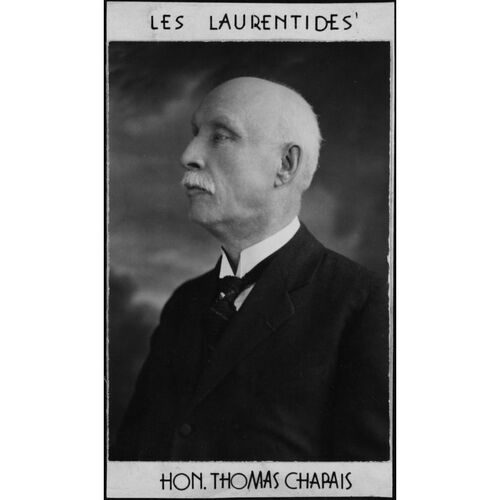

CHAPAIS, Sir THOMAS (baptized Joseph-Amable-Thomas), civil servant, journalist, historian, and politician; b. 23 March 1858 at Saint-Denis (Saint-Denis-De La Bouteillerie), Que., son of Jean-Charles Chapais*, a politician, and Henriette-Georgina Dionne; m. 10 Jan. 1884 Hectorine Langevin (d. 4 Oct. 1934) in the parish of Notre-Dame de Québec; they had a stillborn child; d. 15 July 1946 at Saint-Denis and was buried there three days later.

Family background and influences

Thomas Chapais came from an upper-class Conservative family. His maternal grandfather, Amable Dionne*, was a merchant, seigneur de La Pocatière, and mla for Kamouraska in Lower Canada’s House of Assembly. Despite his initial support for the 92 Resolutions [see Louis-Joseph Papineau*], Dionne agreed, in the wake of the troubles of 1837, to sit on the Special Council for Lower Canada and the Legislative Council for the Province of Canada. Thomas’s paternal grandfather, Charles Chapais, a merchant and lieutenant-colonel in the militia, organized lodging in Kamouraska County for British troops on their way to the district of Montreal during the uprising of 1838. His father, Jean-Charles, also a merchant, became the mp for Kamouraska in 1851 and entered the cabinet of Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché* and John Alexander Macdonald* as commissioner of public works in 1864. Acknowledged as a Father of Confederation, he took part in the Quebec conference and was appointed to the Senate shortly after the British North America Act came into effect.

Young Thomas grew up in a close-knit, devout family. His native parish was heavily influenced by the years of ministry of its founder, the austere Abbé Édouard Quertier*, who also established the Société de Tempérance (known in English as Black Cross). Chapais, who was active in the temperance movement for decades, deeply admired Quertier, to whom he would refer in Discours et conférences as an “apostle of temperance and benefactor of the people.” In 1850 and 1860 the Chapais fiefdom was also characterized by fierce political struggles between the Bleus and the Rouges. Electoral violence in the riding of Kamouraska reached its height in 1867, when a riot led the authorities to cancel the first elections, both federal and provincial, held after confederation [see Sir Charles-Alphonse-Pantaléon Pelletier*].

Chapais was therefore brought up in a highly politicized family atmosphere. “[C]onservative by tradition and conviction” is how he would describe himself in an article published on 4 March 1884 in Le Courrier du Canada. His father’s election campaigns permeated his youth. Throughout his life Thomas would associate the Liberal Party with the peril of republicanism and, conversely, the Conservative Party with order and tradition. In an 1875 letter, which was later reproduced in Mémoires Chapais, Henriette-Georgina Chapais wrote to her adolescent son: “Always be firm and strong in these principles that safeguard our faith and nationality and never allow yourself to be indoctrinated by the Liberals who will ruin our fine country and lead it into materialism, if we let them.”

Eduaction

After completing elementary school in Ottawa and Saint-Denis, Thomas Chapais entered the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière in 1868. He was a gifted student, especially in languages, and had an early interest in history. In 1875, when he was 17, Chapais was admitted to the faculty of arts of the Université Laval in Quebec City, where he was awarded a baccalauréat ès arts the following year. He devoured books, set himself an ambitious reading program, and began to build what would become one of the largest private libraries in the Quebec City region. At the age of 22 he devoted almost 20 per cent of his monthly salary to buying books, mainly fiction and history.

Chapais entered the Université Laval’s faculty of law in September 1876. During this period, he was active, along with his brother Jean-Charles, in the Cercle Catholique de Québec [see Jean-Étienne Landry*], which held strong ultramontane views. At the college he had already been influenced by Abbé Alexis Pelletier*, professor of rhetoric and sworn opponent of liberalism. An admirer of the journalist Louis Veuillot of France and sympathetic to ultramontane theories, the young man nevertheless trod carefully in his interactions with the archdiocese of Quebec and the Université Laval, favourite targets of the ultramontanes. Loyalty to the Conservative Party prevented him from joining the “Castors” in his youth [see Louis-Adélard Senécal*; François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel*]. He was, at the core, too closely tied to the establishment to give a completely free rein to his ultramontanism.

Lawyer, secretary, and journalist

Chapais obtained his law degree with honours from the university in 1879 and won the second Prix Tessier. Before his admission to the Quebec bar that year, he had written to his father (in a letter reproduced in Mémoires Chapais), “I assure you that I have no illusions and am waiting, with no enthusiasm, for the day I am admitted to the legal profession.” A fortuitous offer, however, changed the course of the young man’s career. Much to the annoyance of his father, who wanted to see him enter a law practice, Chapais became private secretary to the new lieutenant governor of Quebec, Théodore Robitaille*, in August. A former Conservative minister in Ottawa and Quebec City, Robitaille took up his duties at the height of the political crisis that followed the dismissal of Lieutenant Governor Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just. The young secretary’s constitutional knowledge, acquired through his family background, his reading program, and his legal training at the Université Laval, most certainly helped the lieutenant governor manage the fallout from the crisis.

Serving with Robitaille at his residence, Spencer Wood, for just over five years, the length of the vice-regal term, Chapais acquired a taste for high-society life. He pursued his reading as well and remained involved with the Cercle Catholique de Québec. It was during this period that he began his journalistic activities. Starting in January 1880, he wrote a series of letters from Quebec City that appeared under the name Héraclite in Le Canada, a Conservative newspaper published in Ottawa. He also began contributing to the Courrier du Canada [see Léger Brousseau*], a Quebec daily. That year he initiated a long career in public speaking, presenting a paper titled “La Nationalité Canadienne-Française” at the Cercle Catholique de Québec. A sought-after speaker, he released four collections of his Discours et conférences in Quebec between 1897 and 1943.

Marriage, family, and friendships

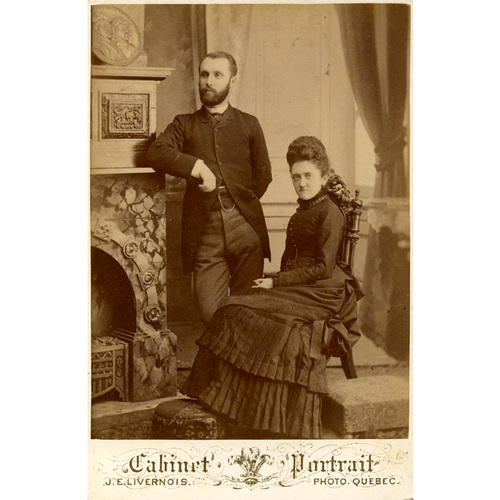

In January 1884 Chapais cemented his status within the French Canadian establishment by marrying Hectorine, daughter of Sir Hector-Louis Langevin*, a Father of Confederation and minister of public works in the government of Conservative prime minister John A. Macdonald. Their marriage not only sealed the alliance between the Chapais and Langevin families, at the top of both the social and political hierarchy, but was also a very compatible union founded on genuine mutual love. They were grief-stricken by the stillbirth of their infant in 1888 and would remain childless.

Very attached to his family and native parish, Chapais maintained a close relationship with several female relatives, including Julienne Barnard, daughter of his sister Amélie and author of Mémoires Chapais, a work in three volumes that relates the family history. Even though he would oppose women’s suffrage, Chapais frequently exchanged political news with his wife, sisters, and nieces, and his private correspondence contains many political confidences.

He also developed a long-lasting friendship with the future archbishop of Montreal, Paul Bruchési*. The two young men, who had been influenced by ultramontane theories in the 1880s, shared a passion for literature. According to the historian Jean Bruchési, Paul’s nephew, “the Chapais house, both at Quebec and Saint-Denis, welcomed the abbé[,] who felt almost at home among them.” Later, when he became bishop, Bruchési would consult Chapais on numerous issues and count on the politician, again as reported by Jean, to exercise his influence “so that the right principles prevail.”

Leadership role in French Canadian journalism

Shortly after his marriage, Chapais was offered the editorship of the Courrier du Canada, an opportunity created by the departure of his friend and relative Narcisse-Eutrope Dionne*. Langevin, a former editor of the newspaper, advised him to accept the position, seeing it as a way into the legislature for his son-in-law. Chapais went ahead and took the helm of the Courrier du Canada in 1884; six years later he would purchase it (and its weekly edition, Le Journal des campagnes). Founded in 1857, the “newspaper of Canadian interests,” as its masthead announced, was a Conservative Party organ [see Joseph-Charles Taché*]. The young editor certainly did not depart from the affiliation. “In politics we are conservative,” he wrote in his newspaper on 4 March when he took up his appointment. “And by this word, we do not mean to denote this or that party affiliation or personal preference. [It] is our ideas, inclinations and aspirations that are conservative. Suffice it to say [that] the most conservative principles are our principles, that the … most conservative measures are our measures, that the most conservative men are our men.”

Chapais rose rapidly among the ranks of leaders in French Canadian journalism. He engaged in polemics with Joseph-Israël Tarte* of Quebec City’s Le Canadien, constantly assailed the Liberals, and commented on the politico-religious issues that were shaking France and Italy. In 1885 he was dismayed by the hanging of Louis Riel* [see The North-West Rebellion of 1885], but he was even more concerned about the possible resignations of the French Canadian ministers in Ottawa. In the 1890s he would fight a fierce battle against the school and language policies of the Manitoba government, and then against the compromise reached between the federal Liberal prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier*, and Manitoba’s Liberal premier, Thomas Greenway*, that put an end to the Manitoba school question [see The Laurier–Greenway Agreement (1896)].

Chapais also discussed literary subjects and embraced the nationalist approach to literary criticism, which placed a high value on conservative, moralizing works. In 1881 he delivered an important lecture at the Institut Canadien de Québec, in which he praised 17th-century French authors and criticized the work of Victor Hugo. He also played a major role in inscribing the name of the writer Laure Conan [Félicité Angers*] into the French Canadian literary canon. Chapais and Conan were also closely linked to the temperance movement.

Provincial appointments

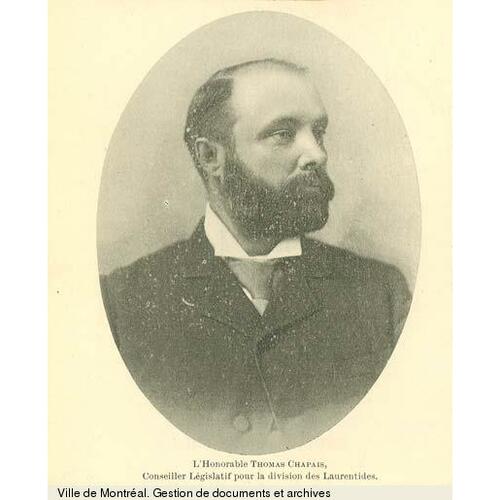

Very active in Quebec’s political arena, Chapais had connections with the right wing of the Conservative Party. He campaigned for several of its candidates in Kamouraska riding, where he himself stood as a candidate in the federal election of 1891 and lost to Liberal Henry George Carroll*. The following year, however, Charles Boucher* de Boucherville, the Conservative premier with ultramontane sympathies, had him appointed to the province’s Legislative Council for the division of Laurentides. Chapais would occupy the position until his death, and he also sat as government leader on the council and minister without portfolio (1893–96) in the cabinet of Conservative premier Louis-Olivier Taillon*. In addition, he was president of the Executive Council (1896–97), commissioner of colonization and mines (1897) in the cabinet of Conservative premier Edmund James Flynn*, and speaker of the Legislative Council (1895–97).

Chapais played a significant role in Quebec politics. As a legislative councillor with close ties to the ultramontanes, he successfully opposed a series of educational reforms during this decade, particularly those proposed by the Liberal government of Félix-Gabriel Marchand*. For example, it was partly owing to Chapais that Marchand failed in his attempt to create a department of public education in 1897 and 1898. The Legislative Council’s Conservative majority, led by Chapais, formed a centre of resistance to the premier, who tried in vain to abolish the chamber in 1900. Chapais enjoyed the trust and support of high-ranking clergymen in his fight against the Liberal government’s reforms [see Paul Bruchési]. He had also been appointed to the Roman Catholic Committee of the Council of Public Instruction in 1892.

Federal government work

With the death of Premier Marchand in 1900, the provincial Liberals’ drive to reform slowed and Chapais gradually refocused his political work on Ottawa, where he engaged in low-key lobbying. He attempted to change several policies of the Conservative government led by Sir Robert Laird Borden*, generally without success. He refused, for example, an appointment to the Senate during the conscription crisis because he could not support the measure. Within the Conservative Party he lobbied more intensely to convince the Ontario government to abolish or soften Regulation 17 [see Sir James Pliny Whitney*].

Historical writing

As the librarian Jean-Charles Bonenfant* would later write in the introduction to Thomas Chapais, it was thanks to the “abundant leisure [enjoyed by] the Opposition” and “the quietude of the Legislative Council” that Chapais had been able to “dedicate the greatest part of his life to literature and leave quite a considerable body of work.” From the late 1890s the politician devoted himself increasingly to history. He already enjoyed a certain reputation in the field, having published in 1882 a long critical note titled “Montcalm et le Canada français” in Nouvelles soirées canadiennes, and having delivered a masterful address on the battle of Carillon (Ticonderoga, N.Y.) four years later at the Cercle Catholique de Québec.

In 1897, when the Conservatives were embarking on their journey through Quebec’s political wilderness, Trefflé Berthiaume*, proprietor of La Presse, who had been appointed to the Legislative Council the previous year on the recommendation of Premier Flynn, invited Chapais to write a Canadian history column in his daily newspaper. Published under the Latin pseudonym Ignotus (signifying “unknown”), his “Notes et souvenirs” appeared twice monthly until 1910; ironically, everyone knew the identity of the author concealed behind the pseudonym. The 260 columns dealt with varied subjects: the salt smugglers in New France (6 Aug. 1898); the introduction of horses to Canada (8 Oct. 1898); the “lapses” of the Patriote party leader, Louis-Joseph Papineau (26 Jan. 1901); and the instructions given by London to Governor James Murray* (11 Jan. 1908). Political stories predominated, and although the format no doubt favoured short news items, historical themes gradually gained ground.

Chapais’s work as a historian really had its origins in his La Presse columns. Yet there were obvious signs of his journalistic background. The first columns signed Ignotus were of uneven quality and largely inspired by minor news items. His commentary improved, however, from 1901, when the Courrier du Canada ceased publication, having failed to adapt to the new realities of mass journalism and leaving Chapais without daily work. Ignotus now cited and analyzed archival documents with increasing frequency and regularly referenced historical writings, especially those of Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix* and François-Xavier Garneau*.

Not formally trained as a historian, Chapais owed much to his reading. As reproduced in Mémoires Chapais, at age 18 he had already written the following as part of a study and reading plan: “I should read Cantu’s universal history, and a good history of England, the one by Lingard or the one by Lord Macaulay.” For his European reading list, he focused on historians of antiquity and 17th- and 19th-century France. Among Chapais’s Canadian references Garneau figured prominently, and he both admired and criticized the historian. In particular, Chapais disagreed with his sharp divergence from the orthodoxy of French Canadian traditionalism. Garneau’s thinking had crystallized early in the 19th century, well before the Catholic revival of the 1840s and 1850s. Chapais would therefore state in a 1925 lecture reproduced in Discours et conférences that Garneau had not “sufficiently illuminated the providential mission of French Canada” and had not known how to combine “the love of the Church … with the love of the homeland, in this intimate fusion which is the very essence of our Canadian patriotism.”

Two extensive biographies

In 1904 Chapais published his first extensive work in Quebec City: Jean Talon, intendant de la Nouvelle-France (1665–1672). This well-documented biography confirmed Chapais as more than a columnist: he had become a historian contributing to the advancement of knowledge. Another biography was released (also in Quebec City) in 1911: Le Marquis de Montcalm (1712–1759). Prepared long before (he had been interested in the Seven Years’ War since his early twenties), the book made use of previously unknown sources. Awarded prizes by the Académie Française, the biographies of Jean Talon* and Louis-Joseph de Montcalm* were, according to Bonenfant, “the first two good monographs of our historical literature. They compare favourably with the works that the English Canadian historians, better trained in historical disciplines, were publishing at that time.”

Professor of history and historian

Appointed professor of history at the Université Laval’s Quebec City campus, Chapais inaugurated its renowned chair of Canadian history in 1916. He took over the courses once given by Abbé Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland*, whose death in 1865 had brought an end to the university-level teaching of Canadian history in the province for almost 50 years. Delivered mostly before an audience of the social establishment, Chapais’s history lectures followed on chronologically from those of Abbé Ferland, which ended with the British conquest. He published the content of his lectures in two stages in Quebec City: the first four volumes covering 1760–1841 appeared between 1919 and 1923, and the final four covering 1841–67 were released between 1932 and 1934, the year he retired from his professorship. Written in the expected oratorical style, the Cours d’histoire du Canada, which enjoyed wide distribution among the well-read public and a favourable reception from the critics, remains his most important work, especially the first four volumes.

Chapais’s appointment was his university’s response to the 1915 hiring by the Université Laval in Montreal of Abbé Lionel Groulx* as professor of Canadian history. Groulx, a rising star of the Quebec nationalist movement, developed a vision of Canadian history that questioned the strongly held ideas of the loyalist school, which had been inaugurated in the early 19th century by Joseph-François Perrault* and whose main representative in the early 20th century was Chapais.

Like most French Canadian loyalists, Chapais emphasized the benefits of the conquest of 1760, the benevolence of the British authorities towards French Canadians, and the superiority of Great Britain’s political institutions. The idea that God had ordained the British conquest underpinned Chapais’s loyalty. Although on the surface it appeared disastrous, the conquest, as he wrote in his Cours d’histoire du Canada, had nevertheless granted “three-quarters of a century of tutelary isolation” to French Canadians, thereby allowing them to escape American revolutionary turmoil and appropriation of territory. Chapais also emphasized the British government’s conciliatory gestures, especially the promulgation of the Quebec Act in 1774 and the Constitutional Act in 1791. He was critical of the political institutions of the ancien régime of France and lauded those of Great Britain. In his view British parliamentarianism was a powerful tool for preserving the French fact in America, while the Crown guaranteed political freedoms and national rights to French Canadians.

A deeply religious historian, Chapais was clearly determined to write history from the point of view of the Roman Catholic Church. Catholicism provided the broad interpretive framework for his writing. He systematically consulted archival sources, examined sometimes with the help of his wife, and reviewed them with a critical eye, except in the case of Indigenous history, when he would often rely on undiscriminating second-hand information.

For Chapais, the quest for truth and the advancement of knowledge lay at the heart of the historian’s approach, which also obliged him to use the lessons of the past to illuminate the present and future. In his case this desire was expressed in concrete terms by actively mobilizing history for political and national ends. Historical references figured prominently in the argument he developed against Regulation 17 in Ontario, for example, and he wrote about the past to serve the Conservative Party and, more generally, conservatism and tradition.

Recognition and durability of his work

Chapais was the most prominent French Canadian historian at the start of the First World War, and he enjoyed great prestige among the well educated. His books sold well. Textbooks of the day incorporated several of his ideas, and he was frequently called upon to clarify controversial points of history. His biography of Talon was translated into English as The great intendant: a chronicle of Jean Talon in Canada, 1665–1672 (Toronto, 1914). He also wrote two articles for the first two volumes of a major English Canadian historiography project, Canada and its provinces: a history of the Canadian people and their institutions…, a synthesis of national and regional history in 23 volumes edited by Adam Shortt* and Arthur George Doughty* (Toronto, 1913–17) [see Robert Pollock Glasgow*].

Beginning in 1902 Chapais participated in the activities of the Royal Society of Canada, of which he was president (1923–24). In 1928 the society awarded him the J. B. Tyrrell Historical Medal for his overall contribution to the field. He was president of the Canadian Historical Association (1925–26) and contributed to the professionalization of the field of history in French Canada, but not to the training of young disciples: his public lectures at the Université Laval did little to educate youth as they were aimed largely at the educated middle class.

The development of intellectual culture in French Canada did not favour the durability of Chapais’s work. The conscription crisis dealt a severe blow to loyalist assumptions and radicalized the nationalist movement, whose figurehead, Abbé Groulx, fired broadsides at the idea of a heaven-sent conquest. For Groulx and his Ligue d’Action Française, the loyalism embodied by Chapais prevented the full realization of the French fact. The abbé encouraged his collaborators to dispute the work of the Laval historian. One of the most scathing criticisms of Chapais came from the polemicist Olivar Asselin* in a lecture titled L’œuvre de l’abbé Groulx…, published in Montreal in 1923: “Son of one of those Tory legislators who demonstrated this kind of naïveté in 1867 in the settlement of the school question, and to whom we shall ultimately owe the break-up of confederation, the sole preoccupation of this conscientious man seems to be to reconcile his compatriots to a regime that is doubly sacred for him. He attaches little importance to natural law, glorifies the right of conquest, [and] leans heavily on books and events to make them witness to the magnanimity of the conqueror.”

Senate

Although challenged by Quebec nationalists, Chapais was far from marginalized politically. In Quebec City, he remained one of the leaders of the Conservative Party and played a prominent role in the Legislative Council, where he defended the freedom of the press in 1922 and vigorously opposed women’s suffrage in 1940 [see Winning the Right to Vote]. In Ottawa in December 1919, Chapais was named to the Senate for the division of Grandville, to burnish the image of the Conservative Party. A defender of the status quo, he entered the Senate at a time when the progressives from the west were protesting strongly against the institution. In 1925 he gave an important speech there against reforming the upper house, stressing that it was “an inherent part of our national constitution. To touch it would be to attack the federal pact; and the old provinces, especially Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island would have the right to consider the attempt as a lack of faith.” He would remain a senator until his death.

Chapais took an even greater part in federal affairs with the return to power of the Conservative Party in 1930 [see Richard Bedford Bennett]. In September, as a Canadian delegate to the eleventh session of the League of Nations in Geneva, he delivered a speech on the rights of minorities. Later, in 1934, he supported the printing of two series of banknotes, one in English and the other in French, a measure that was provided for in the draft legislation incorporating the Bank of Canada and which was strongly opposed in French Canadian nationalist circles.

With his appointment to the Senate in 1919, he became one of the very rare Canadian politicians to sit in the provincial and federal upper chambers concurrently. The dual mandate proved particularly important at the time of the Union Nationale victory in the Quebec provincial election of 1936. Government leader in the Legislative Council (1936–39) and minister without portfolio (1936–38) in the administration of Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*, Chapais to some extent represented the premier in Ottawa. Valuing his loyal service, Duplessis made Chapais, who was one of his few advisers, interim premier during a brief absence in 1938. He saw him as a living connection between his government and the long Conservative reign at the end of the 19th century. Of the members of the Quebec legislature, Chapais held the record for the longest term in office (54 years). His mandate in the provincial upper chamber covered more than half the history of the institution, which was created in 1867 and abolished in 1968.

Although Chapais’s move to the Senate put an end to his most productive period as a historian, he remained active politically and intellectually for another 25 years. In 1942 he opposed conscription for overseas service during the Second World War. In July 1944 he gave a long speech opposing a Senate motion to support the writing of a school textbook that would be used to teach a uniform Canadian history across the country. That year, when the Union Nationale returned to power in Quebec, Chapais entered the cabinet once more, at age 86, as minister without portfolio and government leader in the Legislative Council.

Honours, death, and assessment

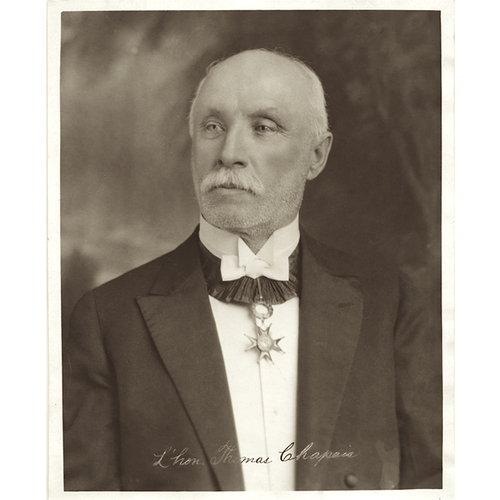

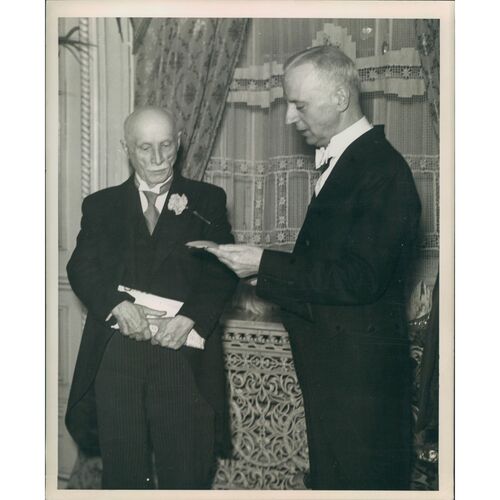

Over the course of his career Chapais received several honours. He was named a chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur in 1902, made a commander of the Order of St Gregory the Great in 1914, and knighted by King George V in 1935. Numerous universities awarded him an honorary doctorate: the Université Laval in Quebec City in 1899, the Université d’Ottawa in 1923 (called at the time the College of Ottawa), Bishop’s University in 1928, Queen’s University in 1932, and the Université de Montréal in 1945.

After a short illness Chapais died in 1946 in Saint-Denis, his birthplace, and was given a state funeral, which was attended by Premier Duplessis and members of his cabinet. The Union Nationale undertook to preserve his memory, and in 1950 the Quebec government purchased his library and part of his archives on behalf of the provincial archives. The following year, Omer Côté, a Union Nationale mla and provincial secretary, took part in a lengthy talk on Radio-Canada about the life and work of the historian and politician. Duplessis would name a forestry town in Chapais’s memory in 1955.

In his native province Thomas Chapais had a significant impact on societal change and yet, in the 21st century, he is primarily remembered as a historian, not as a politician. It is difficult, however, to separate the two commitments. His historical works contain political harangues and his political speeches often contain historiographical clarifications. Chapais remains one of the last great representatives of French Canadian loyalism. As such, his work served as a foil to Quebec nationalist historians in the inter-war period. His concerns as a historian reflect those of a bourgeois conservative of the Victorian age. In certain respects his views on the conquest and British rule, indeed his entire loyalist interpretation, stem from a certain blindness to the economic conditions of French Canadians, conditions of which his main rival and detractor, Abbé Lionel Groulx, was fully aware.

The fundamental manuscript sources on the life and work of Thomas Chapais are preserved in the Chapais family fonds (P225) at the Div. des arch. de l’Univ. Laval and the Thomas Chapais fonds (P36) at the Centre d’arch. de Québec, Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec.

Chapais’s published work can be found first and foremost in newspapers, including Le Courrier du Canada (Québec), 1880–1901, its weekly edition, the Journal des campagnes (Montréal), 1883–1901, and La Presse (Montréal), 1897–1911. Chapais also contributed to the Nouvelles Soirées canadiennes (Québec) in 1882 and L’Événement (Québec), 1902–22, and he published a monthly column devoted to international news in the Rev. canadienne (Montréal), 1899–1922. He also wrote many articles that appeared in La Nouvelle-France (Québec) and Le Canada français (Québec), 1900–30. In 1905 he published Mélanges de polémique et d’études religieuses, politiques et littéraires (Québec), a compilation of some of his newspaper articles. In 1957 a slender volume, Thomas Chapais (Montréal et Paris), comprising works selected by J.-C. Bonenfant, appeared in the “Classiques canadiens” series. Chapais was the author of numerous other titles, which are cited in the more complete list in Elisabeth La Mothe, Bibliographie de l’œuvre de sir Thomas Chapais ([Montréal], 1940) and Fernand Harvey, Bibliographie de six historiens québécois: Michel Bibaud, François-Xavier Garneau, Thomas Chapais, Lionel Groulx, Fernand Ouellet, Michel Brunet (Québec, 1970). His writings are also mentioned in the first two volumes of the Dictionnaire des œuvres littéraires du Québec, sous la dir. de Maurice Lemire et al. (7v., Montréal, 1978–2003).

Other secondary sources on Chapais include: the last volume of Mémoires Chapais: documentation, correspondances, souvenirs (3v., Montréal et Paris, 1961–64) by Julienne Barnard; Le Québec et ses historiens de 1840 à 1920: la Nouvelle-France de Garneau à Groulx (Québec, 1978) by Serge Gagnon; and Making history in twentieth-century Quebec (Toronto, 1997) by Ronald Rudin. His political activities are described in Robert Rumilly’s monumental Histoire de la province de Québec (41v., Montréal et Paris, 1940–69). Several scholarly articles contemplate Chapais’s work, including: J.-C. Bonenfant, “Retour à Thomas Chapais,” Recherches sociographiques (Québec), 15 (1974): 41–55; J.-J. Lefebvre, “La lignée canadienne de l’historien sir Thomas Chapais (†1946)†,” Royal Soc. of Can., Trans. (Ottawa), 4th ser., 13 (1975): 151–68; Pierre Berthiaume, “Thomas Chapais: un discours biblique,” Voix et images (Montréal), 2 (1976–77): 231–39; and Michel Bock, “Overcoming a national ‘catastrophe’: the British conquest in the historical and polemical thought of Abbé Lionel Groulx,” in Remembering 1759: the conquest of Canada in historical memory, Phillip Buckner and J. G. Reid, ed. (Toronto, 2012), 161–85. Finally, the author contributed to studies on Chapais in “Thomas Chapais, loyaliste,” Rev. d’hist. de l’Amérique française (Montréal), 65 (2011–12): 439–72; “Thomas Chapais et le règlement 17,” dans Le siècle du règlement 17, sous la dir. de Michel Bock et François Charbonneau (Sudbury, Ontario, 2015), 279–300; and Thomas Chapais, historien ([Ottawa], 2018).

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin coll.), 1621-1968,” St-Denis-de-la-Bouteillerie, Québec, 8 oct. 1934: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 3 Feb. 2023). Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Québec, CE301-S1, 10 janv. 1884, 30 sept. 1888; Centre d’arch. du Bas-Saint-Laurent et de la Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine (Rimouski, Québec), CE104-S15, 24 mars 1858. Le Devoir (Montréal), 15 oct. 1930; 15–16, 18, 27 juill. 1946. André Beaulieu et Jean Hamelin, Les journaux du Québec de 1764 à 1964 (Québec et Paris, 1965). Jean Bruchési, “Brève histoire d’une longue amitié,” Cahiers des Dix (Montréal), 23 (1958): 217–40. Can., Senate, Debates, 29 April 1925: 173. Omer Côté, Sir Thomas Chapais: causerie radiophonique prononcée en janvier 1951, sur le réseau français de Radio-Canada (s.l., [1951?]). Québec, Assemblée Nationale, “Dictionnaire des parlementaires du Québec de 1764 à nos jours”: www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/membres/notices/index.html (consulted 8 May 2020).

Cite This Article

D. C. Bélanger, “CHAPAIS, Sir THOMAS (baptized Joseph-Amable-Thomas),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 20, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chapais_sir_thomas_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chapais_sir_thomas_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | D. C. Bélanger |

| Title of Article: | CHAPAIS, Sir THOMAS (baptized Joseph-Amable-Thomas) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | February 20, 2026 |