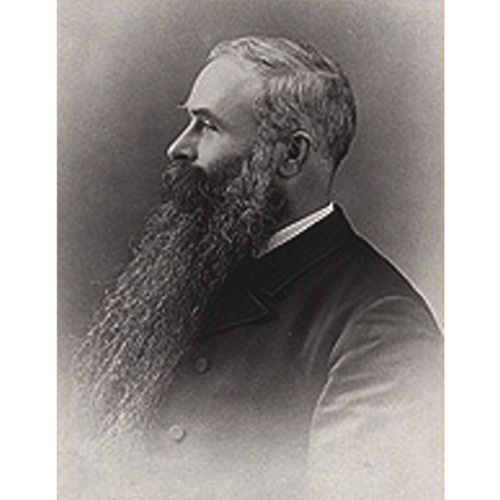

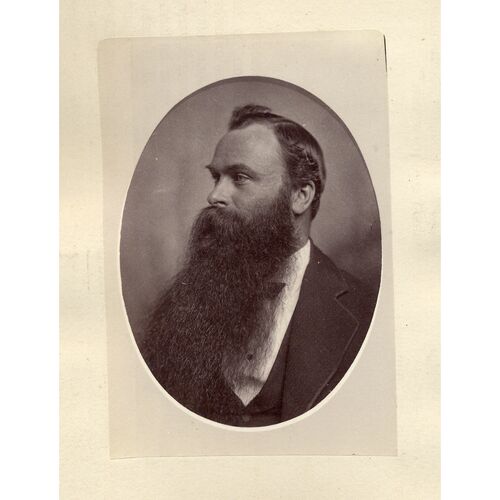

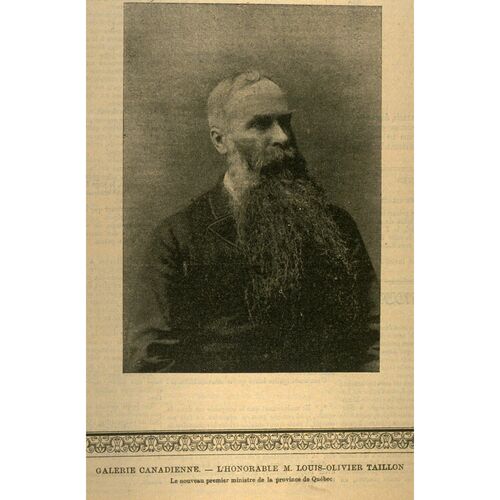

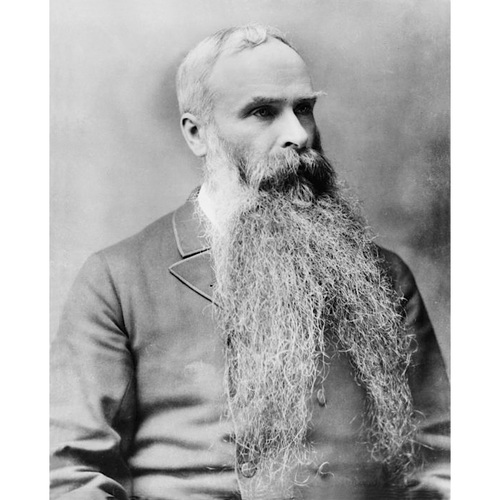

TAILLON, Sir LOUIS-OLIVIER, lawyer, politician, and office holder; b. 26 Sept. 1840 in Saint-Louis-de-Terrebonne (Terrebonne), Lower Canada, son of Aimé Taillon, a farmer, and Josephte Daunais; m. 14 July 1875 in L’Assomption, Que., Georgiana Archambault, widow of Candide Bruneau and daughter of Pierre-Urgel Archambault*, and they had one child, but both mother and child died shortly after the birth in January 1876; d. 25 April 1923 in Montreal.

After studying from 1847 to 1856 at the Collège Masson in Saint-Louis-de-Terrebonne, where his schoolmates included Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau* and Alphonse Desjardins* (1841–1912), Louis-Olivier Taillon resolved to enter the priesthood and he taught at the college for six years before realizing his calling took him elsewhere; he decided to embrace law. He started his clerkship in Montreal in 1862 in the firm Fabre, Lesage et Jetté and finished it under Désiré Girouard*. Admitted to the bar on 6 Nov. 1865, he practised in association with several prominent lawyers, including Sévère Rivard*, François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel*, Fabien Vanasse, Lomer Gouin, and Siméon Pagnuelo. His last partnership would be Taillon, Bonin, Morin et Laramée. On 20 Jan. 1882 Taillon was made a qc and in 1892 he was elected bâtonnier (president) and a councillor of the bar of Montreal.

Taillon had soon become drawn into politics. Like Rivard and Trudel, he was partial to the ultramontane point of view and he helped to promote and formulate the Programme catholique of 1871 [see Trudel], which was designed to bring purity to politics and remake the Conservative party to reflect the subordination of politics to the moral teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. A French Canadian nationalist favouring the absolute authority of the pope in matters of faith and discipline, Taillon had advised the bishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget*, in his dispute with liberal Catholics and particularly with the Sulpicians [see Joseph-Alexandre Baile*] in 1867. He received favourable public attention as one of the organizers of the celebrations in 1874 for the 40th anniversary of the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal [see Louis-Onésime Loranger*]. The following year, supported by the ultramontanes, including Trudel and Desjardins, he sought election to the Legislative Assembly for Montreal East. He won, but his ultramontane ardour probably kept him from a ministerial position.

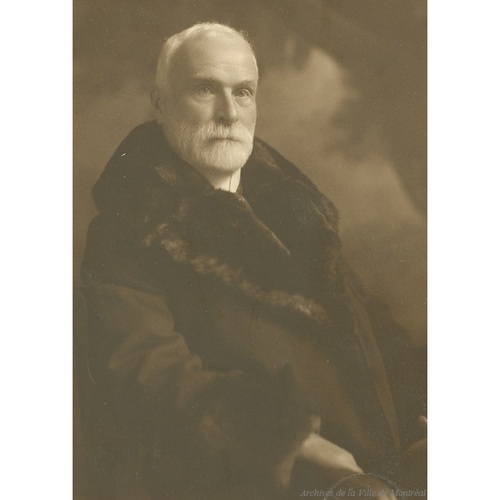

In the assembly, Taillon’s abilities as a forcible speaker and good debater came to the fore. He was a person of principle, but lacked panache. His baritone voice and patriotic songs made him a banquet favourite. Taillon loved musical evenings and after a particularly difficult day he would return home to play his piano and forget the discords of politics. His charming conversation and enjoyable reminiscences gave great pleasure to countless small gatherings. His long flowing beard, which he pulled alternately with his right and left hand when upset or nervous, became his trade mark. He supported the government of Charles Boucher* de Boucherville and promoted the ultramontane agenda. As an advocate of Bourget, he presented in 1875 the bill to erect in civil law parishes cut out from the former Sulpician parish of Notre-Dame. Boucherville’s government had enacted other legislation that year ceding control of education to church leaders.

Taillon backed the government’s attempts to make municipalities, such as Montreal, honour their pledges of financial support for the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway. This policy led directly to the so-called coup d’état of 2 March 1878, whereby the lieutenant governor, Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just, dismissed the Boucherville government and invited the Liberals under Henri-Gustave Joly* to take office. Although the election of 1 May saw the Liberals gain some ridings and stay in office, Taillon kept his seat. He then worked tirelessly under Chapleau, Boucherville’s successor as party leader, to bring the Conservatives to power in October 1879.

Chapleau and Taillon were not always of the same mind, however. Taillon supported the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery in its fight for independence from the Université Laval [see Thomas-Edmond d’Odet* d’Orsonnens]. A member in 1881 of the administrative committee of the diocese of Montreal which dealt with the presence of the Université Laval in Montreal and a member of the legislative committee which adjudicated the question, he had bitter words with Chapleau over this matter. Nonetheless, he ran in the general election of 1881 under Chapleau’s banner and won the largest majority of any candidate. For his work in bringing the Conservatives back into office, his help in by-elections in 1880, and his impressive personal victory, Chapleau proposed him as speaker of the assembly, a position he filled from 8 March 1882 until 27 March 1884, through the administrations of Chapleau and Joseph-Alfred Mousseau*.

When the Mousseau government resigned in January 1884, Taillon accepted the position of attorney general and government leader in the assembly under Premier John Jones Ross* despite his preference for Louis-Rodrigue Masson* as premier; he acted in this capacity from 23 Jan. 1884 to 25 Jan. 1887. Taillon supported Ross’s policy of fiscal restraint and as a legislative tactician he guided the government through the treacherous waters of religious and political disputes. Taillon and Ross became the focus of controversy surrounding the province’s response to the North-West rebellion [see Louis Riel*]. They supported the federal government in its decision to allow Riel to hang, much to the anger of many ultramontanes within the Conservative party, but attempted to keep the province at a distance from this decision. Taillon worried that Quebec’s intervention in a matter of federal concern would lead to a diminution of provincial power. Honoré Mercier*’s ability to bring nationalists together in defence of Riel led to the defeat of the Ross government in the election of October 1886 and to Taillon’s loss in Montreal East. He was elected in Montcalm in December.

In later years Taillon would attribute the defeat of the Ross government not so much to Riel’s execution as to the opposition of certain clergy to the government’s asylum legislation of 1885. The new policy allowed organizations such as the Roman Catholic Church to run mental asylums, but stipulated that in return for financial contributions from the government a medical board appointed by the state would oversee the institutions and their medical staff. Many bishops and clergy feared this intervention would set a precedent for control of similar facilities such as hospitals and thus fought the legislation with vigour. The state won the battle and resentment festered amongst more strident ultramontanes who desired the financial support of the government without any accountability. Taillon was incorrect, however, to see this issue as key to the Ross government’s defeat.

Desperate to remain in power despite their loss in the election, the Conservatives decided that Ross should resign in favour of Taillon; it was thought that he might be able to attract the ultramontanes, who held the balance of power, back into the party fold. The Taillon government took office on 25 Jan. 1887 but failed to gain the support it needed. After losing two votes in the assembly on his choice for speaker, Taillon resigned as premier and Mercier took office on 29 January. The federal Conservatives offered Taillon a place on the Superior Court of Quebec, but, in spite of his protestations to the contrary, Taillon loved politics too much to go to the bench.

As leader of the opposition, Taillon represented Montcalm from 1886 until the general election of 17 June 1890, when he was defeated in the riding of Jacques-Cartier. In addition to attacking Mercier’s profligacy, he criticized him for pitting anglophones against francophones through his actions over the Jesuits’ Estates Act. During the controversy over the Baie des Chaleurs Railway, Taillon was merciless in his criticism of the premier. Indeed, this scandal led to the dismissal of Mercier by Lieutenant Governor Auguste-Réal Angers* on 16 Dec. 1891 and to the return of the Conservatives under Boucherville. Taillon assumed the leadership in the assembly and joined the cabinet as a minister without portfolio, and thus without salary. In the general election which followed on 8 March 1892, he won the seat of Chambly, which he would represent until May 1896. When Boucherville resigned in December 1892 because he refused to work under Chapleau, the new lieutenant governor, Taillon was asked to form a government; he did so on 16 Dec. 1892.

A year later, Taillon’s character was tested in the assembly. On 28 Dec. 1893 Mercier, who was dying from diabetes, defended his probity before his accusers on the government benches. Looking directly at Taillon across the aisle, he explained that the Conservatives had ruined and dishonoured him. Now they wished to trample his corpse. The governing party had taken all his possessions, but not his honour. He had been acquitted of the charges of corruption against him. In this charged atmosphere, Taillon rose, walked across the aisle, and gave his hand to Mercier. Within a year, Mercier was dead and Taillon’s reputation as a decent man remained intact.

As premier, Taillon was an administrator rather than a political leader and his government imposed a hard regime of economy in the aftermath of Mercier’s spendthrift government. His reduction of subsidies to railway companies and his tax increases were highly unpopular in Quebec. Like Mercier and Boucherville, Taillon was very supportive of agriculture. The results were promising. Quebec cheese placed in the top categories at the Columbian exposition in Chicago in 1893. That year the Trappists of Oka placed their famous cheese on market. Taillon also followed his immediate predecessors in supporting the timber companies developing the Lac-Saint-Jean region. The critical issue during his tenure was the Hall affair. John Smythe Hall*, the provincial treasurer, did not want to renew a loan the government had obtained from France in 1891. He wished to borrow money through London and through his English-speaking sources in Montreal while Taillon favoured renegotiating with the Crédit Lyonnais and the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas. Taillon won this battle, but in the process he lost support from the English-speaking business community and Hall resigned. Taillon held the post of provincial treasurer, as well as the premiership, from 6 Oct. 1894 until his government resigned in 1896.

A question within the jurisdiction of the federal government but one which caused enormous problems for Taillon personally and the federal Conservative party in general was the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*]. The failure of the federal Conservatives to conclude this matter led to bitter divisions within the party. In an effort to keep the federal Conservatives in power and win the federal general election of June 1896, Taillon resigned as premier on 11 May and joined his colleagues Desjardins, Angers, and Ross in the newly formed government of Sir Charles Tupper* as postmaster general. Taillon and his friends had strong ties with the church and favoured federal legislation to override provincial wishes and restore Catholic schools to Manitoba. They suffered defeat at the hands of Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberals, however. Taillon lost in Chambly-Verchères and resigned from the cabinet on 8 July. He had never won a provincial election as Conservative leader and he would never win a federal seat.

Following his defeat, Taillon continued to work for the Conservatives. He refused to meet with the apostolic delegate Rafael Merry del Val, whom Rome had sent at Laurier’s request, but in opposition to the wishes of most of the Catholic hierarchy, to establish the facts and re-establish peace within the Catholic Church over the Laurier-Greenway agreement, which was designed to resolve the prickly school question. Taillon rejected that settlement as a betrayal of Roman Catholics in Manitoba and spoke against it. He maintained that the Liberals exploited the issue for political gain and that the Liberal leadership generally favoured non-confessional schools. Not surprisingly, he ran, unsuccessfully, in the federal general election of 1900, standing for Bagot. There again he spoke against the agreement out of principle and pledged not to let the matter drop until the population had awakened to the treason of their leaders.

Although he never ran again for a seat in either the provincial legislature or the federal parliament, Taillon continued to support the Conservatives publicly until his death. Like many of them he was ambivalent about the South African War, and he spoke out only to condemn Laurier for sending troops without consulting parliament. Supporting Conservative policy, he spoke in opposition to the establishment of a Canadian navy proposed by the Naval Service Bill in 1910. For his service to the party Sir Robert Laird Borden* appointed him postmaster in Montreal after the Conservative victory in 1911. He held this position until 1915 when he made way for another party stalwart, Joseph-Gédéon-Horace Bergeron. In return, Taillon was made a knight bachelor in the New Year’s honours list of 1916. During this period, Taillon offered to write his memoirs if the province would pay for a stenographer. The Liberal government of Sir Lomer Gouin refused and left us all the poorer for that decision. Before the election of 1917 Taillon was appointed president of the French section of the Unionist organization in Quebec and spoke out in an effort to rally French Canadians to conscription.

Sir Louis-Olivier Taillon came to be regarded as the “grand old man” of the Conservative party. During his long career, he was active in many areas. He served as a commissioner for the Municipal Loan Fund from 1880 to 1882; he was vice-president of the Liberal-Conservative Club of Montreal in the 1890s; he helped to found and was the first president of the Club Lafontaine in 1903; he was prominently identified with the Ligue Antialcoolique de Montréal in 1907; and he was elected a director of the Banque Internationale du Canada in 1911. In 1895, while premier, he had received an honorary dcl from Bishop’s College at Lennoxville and in 1901 he received an honorary lld from the Université Laval at Montreal. Towards the end of his life he gradually lost his sight and by 1922 he had cut off his beard, his political trade mark. A man of slender means, generous with his time and his money, Taillon lived his entire life in humble circumstances and spent his last years in the Institution des Sourdes-Muettes on Rue Saint-Denis in Montreal. A close adviser to Arthur Sauvé*, the leader of the provincial Conservative opposition from 1916 to 1929, he remained active politically behind the scenes until the day he died.

Four speeches given by Sir Louis-Olivier Taillon are listed in CIHM, Reg.

ANQ-M, CE605-S14, 14 juill. 1875, 27 janv. 1876; CE606-S24, 27 sept. 1840. Arch. de la Chancellerie de l’Archevêché de Montréal, 778.867 (hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu). Le Devoir, 26, 28 avril 1923. Gazette (Montreal), 25 Jan. 1876, 26 April 1923. Pierre Beullac et Édouard Fabre Surveyer, Le centenaire du barreau de Montréal, 1849–1949 (Montréal, 1949). J. D. Borthwick, History and biographical gazetteer of Montreal to the year 1892 (Montreal, 1892). Canadian annual rev., 1916, 1923. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). L.-O. David, Mes contemporains (Montréal, 1894). Andrée Désilets, Hector-Louis Langevin, un Père de la Confédération canadienne (1826–1906) (Québec, 1969). DPQ. [Jacqueline] Francœur, Trente ans rue St-François-Xavier et ailleurs (Montréal, 1928). Le Jeune, Dictionnaire. P.-B. Mignault, “Louis Olivier Taillon,” Les hommes du jour: galerie de portraits contemporains, L.-H. Taché, édit. (32 sér. en 16v., Montréal, 1890–[94]), 31e sér.: 481–92. Newspaper reference book. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec; Hist. de Montréal. George Stewart, “The premiers of Quebec since 1867,” Canadian Magazine, 8 (1896–97): 289–98.

Cite This Article

Kenneth Munro, “TAILLON, Sir LOUIS-OLIVIER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/taillon_louis_olivier_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/taillon_louis_olivier_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kenneth Munro |

| Title of Article: | TAILLON, Sir LOUIS-OLIVIER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |

![[Louis-Olivier Taillon] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis Original title: [Louis-Olivier Taillon] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis](/bioimages/w600.7200.jpg)