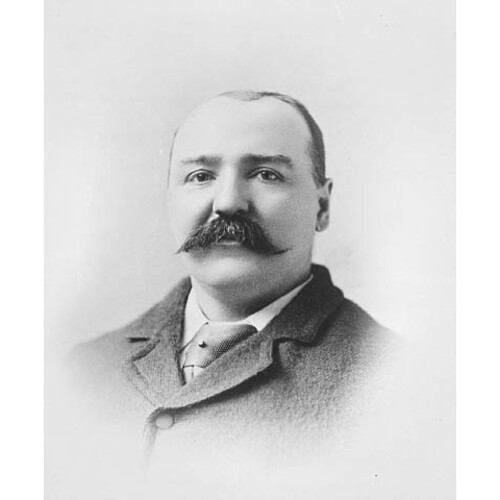

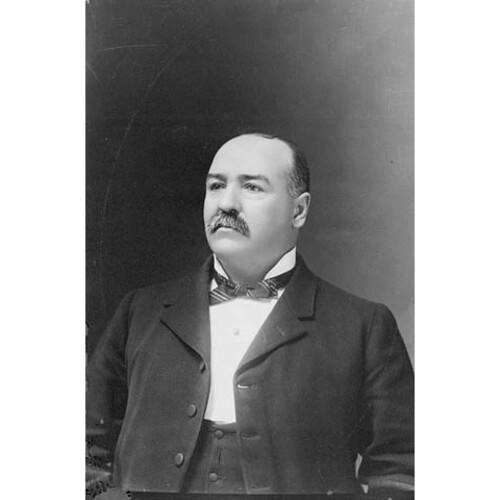

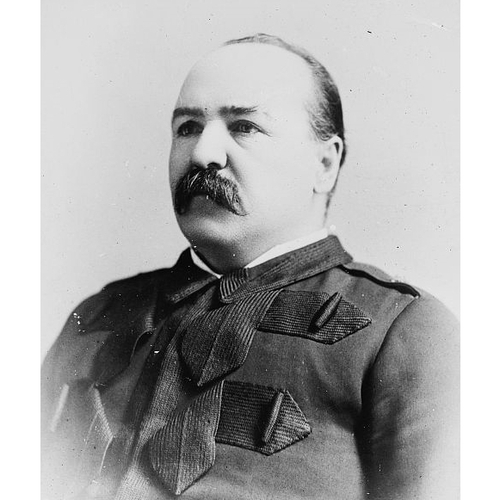

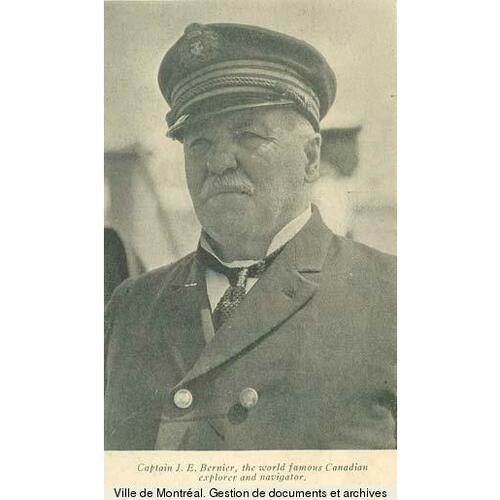

BERNIER, JOSEPH-ELZÉAR (baptized Marie-Joseph-Eléazar), ship’s captain, shipbuilder, harbour master, businessman, prison warden, and explorer; b. 1 Jan. 1852 in L’Islet, Lower Canada, son of Thomas Bernier and Henriette-Célina Paradis; m. first there 8 Nov. 1870 Rose Caron (d. 18 April 1917), and in 1885 they adopted Elmina Caron, the nine-year-old daughter of his cousin Philomène Caron (née Boucher); m. secondly 1 July 1919 Alma Lemieux in Ottawa, and they had a stillborn son; d. 26 Dec. 1934 in Lévis, Que.

A nautical life

Joseph-Elzéar Bernier was born in the village of L’Islet, on the southern bank of the St Lawrence River. His father and paternal grandfather were ship’s captains with over a century of experience between them. Joseph-Elzéar was educated at the institution run by the Brothers of the Christian Schools in L’Islet until about age 12, when he began working with his father on the construction of the Saint-Joseph, a seagoing brigantine. When in 1869 Joseph-Elzéar took command of the ship, he was just 17 years old and among the youngest ship’s captains in the world. A year later he married Rose Caron, a L’Islet girl of 15; she remained in her parents’ home and he returned to the sea.

In 1872 Bernier attended the navigation school in Quebec City, which had been set up that year by the Department of Marine and Fisheries, and received his master’s certificate of competency. He and Rose soon moved to Saint-Sauveur (Quebec City). He spent most of the next 15 years delivering ships and cargo across the Atlantic on behalf of Ross and Company [see James Gibb Ross*], Quebec City’s foremost shipbuilder. From 1874 to around 1878, he also managed the shipyard at Hare Point, along the Saint-Charles River. Between 1869 and 1887 Bernier’s Atlantic crossings averaged 22 days, and his record was a 17-day journey from Quebec City to Liverpool, England. He would make over 250 transatlantic voyages during his lifetime. In 1887 he accepted a three-and-a-half-year contract, at $1,200 per year, as harbour master of Lauzon (Lévis), opposite Quebec City, declaring in his journal that he had come ashore for good.

Prison warden

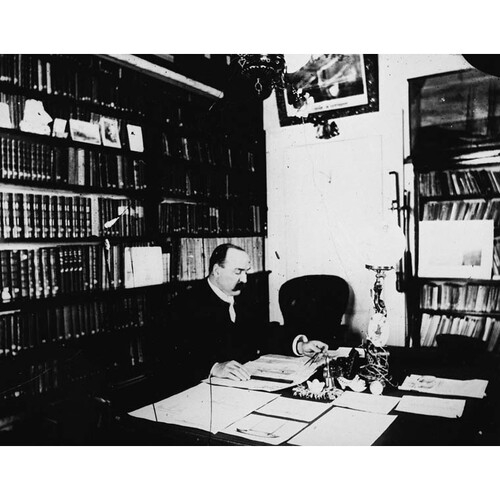

Nonetheless, when his term as harbour master ended, Bernier did not renew it but instead returned to his love of seafaring, accepting some private contracts. In the spring of 1894, he founded the Dominion Ice Company in Saint-Henri (Montreal) with a brother and a cousin. He helped manage the enterprise until the following year, when the provincial Conservatives led by Louis-Olivier Taillon* appointed him warden of the Quebec City jail (at $900 annually plus room and board), with Rose as head matron (at $200 per year). The position was a patronage plum for Bernier, who had worked on the party’s campaigns in L’Islet in 1887 and 1892. The job left him with enough free time to study Arctic exploration, a topic that had long fascinated him. He was determined to be the first person to reach the North Pole and soon developed a plan to realize his goal. Mimicking Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen, Bernier wanted to plant a ship in the Arctic ice pack and let it drift over the pole. Nansen had failed, but Bernier believed that he had the nautical expertise to better gauge wind and water conditions when determining where to enter the ice. His term as warden ended with a whiff of scandal related to his alleged running of a winery out of the jail. On 6 Nov. 1897 the Quebec Morning Chronicle reported on a rumour that the investigation had uncovered no proof of wrongdoing on his part, while another article in the same newspaper announced his scheme to mount an expedition to the North Pole. He nevertheless remained in the role of warden until the following March, although it is unclear whether he ultimately resigned or was dismissed.

Campaigning for Arctic exploration

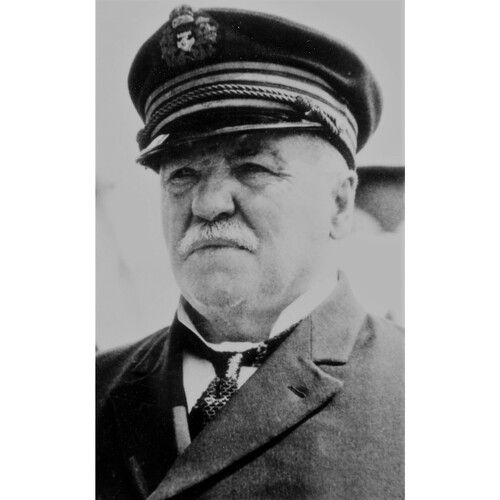

Between 1898 and 1903 Bernier ran a tireless cross-country campaign to raise money and support for his proposed polar trek. The press simultaneously loved and lampooned him. At about five feet three inches and around 200 pounds, he was a little bull of a man. Anglophone newspapers caricatured his thick Quebecois accent, while francophone newspapers noted that his French was not of high quality either. This lack of fluency was no doubt the result of leaving school at about age 12 and then speaking English for decades while working. His authority as a seaman was beyond dispute, however, and many Canadians, particularly French Canadians, were proud to have one of their own involved in polar exploration. He gave hundreds of lectures, obtained corporate sponsorships, and secured as patron Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*]. As there was no other Canadian initiative underway to explore beyond the north of the country’s mainland, let alone to reach the pole, Bernier’s campaign attracted considerable national attention. At the turn of the 20th century, Canada’s most vocal advocate for Arctic exploration was an almost 50-year-old sailor who had never explored the north or any unknown territory anywhere.

Bernier was unable to win over the one person whose support he needed, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*. Government backing was vital both for funding and for making the expedition official. Laurier resisted in part because of the cost, which fluctuated in Bernier’s telling from $75,000 to $200,000. More importantly, the Laurier administration was coming to terms with the fact that the United Kingdom’s 1880 transfer of its Arctic possessions had been insufficient to give Canada clear title, and that a systematic approach needed to be developed to assert its sovereignty in the region. Bernier’s proposal – to float over the pole a single time – was the very antithesis of systematic. The government was concerned not only that his plan was unlikely to strengthen Canada’s claim to the broader region, but also that it could actually undermine its strategy.

Subarctic expedition, 1904–5

Growing international activity in the north – particularly Norwegian explorer Otto Neumann Sverdrup’s discovery of a group of islands there during his 1898–1902 expedition and the Alaskan Boundary Tribunal’s favouring of the American position in 1903 – led the Laurier government to take action. In 1904 the Department of Marine and Fisheries hired Bernier to go to Germany and purchase the Antarctic exploration steamship Gauss. Considering that the captain had specifically cited the Gauss as the kind of ship he required, it was widely assumed that Bernier was getting approval for his polar expedition, whereas in fact the government’s plan was to have the Gauss, renamed the Arctic, assert Canadian sovereignty by patrolling northern waters. Major John Douglas Moodie of the Royal North-West Mounted Police would command the expedition and Bernier would captain the ship. In his memoirs Bernier insists that he had been deceived, but his correspondence makes clear that he knew the nature of the planned voyage even before heading to Germany.

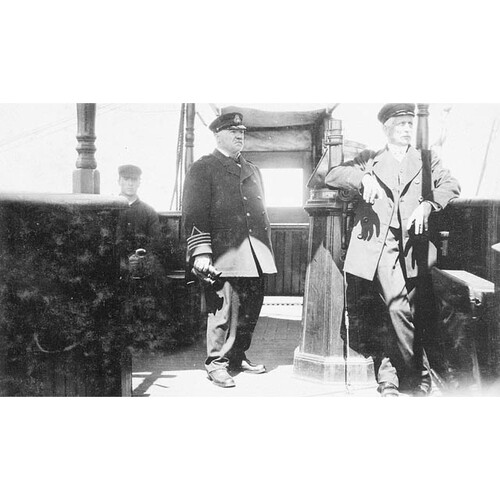

Bernier left for northern Hudson Bay on 17 Sept. 1904 with a crew of 47 that included, among others, a doctor, police officers, an artist/photographer, and even a historian to record the expedition. They overwintered in Cape Fullerton (Nunavut) before returning to Quebec City on 7 Oct. 1905. Both Bernier and his ship had performed well during their first voyage to subarctic regions. Afterwards, however, a scandal erupted regarding accusations that the expedition had been supplied in a corrupt and lavish manner. Bernier’s purchase of 4,000 Laurier-brand cigars from the Rock City Cigar Company of Lévis drew special attention in the House of Commons. It is striking that, even before a mainly Liberal parliamentary committee dismissed the allegations against the Department of Marine and Fisheries, the opposition and the media placed very little blame on Bernier, the man ultimately responsible for supplying the expedition. Despite the scandal his reputation on Arctic matters was solidifying in Canada and internationally – he was elected a vice-president of the New York–based Arctic Club of America that year – and he was becoming Canada’s Arctic champion, if only by default.

First Arctic expedition, 1906–7

The federal government sent Bernier north again aboard the Arctic in 1906. This time he was in direct command of the expedition, his first above the Arctic Circle. Besides patrolling northern waters, he was to issue licences to international whalers and lay claim to all lands – not just new ones – that he came upon. It is unclear whether this last instruction was an intentional shift in Laurier’s Arctic policy to expand Canada’s means of asserting sovereignty. It nonetheless suited Bernier very well because raising flags and taking possession of already-discovered territories tied him more firmly to the British explorer tradition. Setting sail from Quebec City on 28 July 1906 with a crew of 40, Bernier would claim a whole host of islands, including Baffin (Nunavut) and Melville (N.W.T. and Nunavut), well aware that others had done so long before him.

In February 1907, while Bernier was overwintering in the north, his long-time political supporter Pascal Poirier argued in the Senate for what would become known as the sector principle: that northern nations such as Canada could legitimately claim all the territory from their western to eastern boundaries, all the way north to the pole. Poirier would become associated with this concept of international polar law, but in his speech he credited Bernier for advancing the idea at the Arctic Club of America a year earlier.

The Arctic returned to port in Quebec City on 19 Oct. 1907. Earlier that month, while still in the north, Bernier had written a letter to his Ottawa superiors detailing what he had accomplished. He noted in passing that on 12 August, at the voyage’s northernmost point, off Ellesmere Island (Nunavut), he had taken possession of all adjacent islands “as far as ninety degrees north” – that is, all the way to the North Pole. There is a small handwritten “X” beside this phrase in the margin of Bernier’s letter, suggesting that government officials rejected his phrasing because it implied a blanket claim to the entire Arctic Archipelago. Bernier never referred to it in such terms again. It would seem he had learned that the Laurier government did not want him to make a sector claim, and that if he were to make one regardless, it could not be by half measure.

Second Arctic expedition, 1908–9

Captain Bernier had never given up his dream to be the first to reach the pole. With Americans Robert Edwin Peary and Frederick Albert Cook both planning expeditions there in 1908, there was more reason than ever for the Canadian government to assert its presence in the region. The Arctic was sent north again. Departing from Quebec City on 28 July with a crew of 42, Bernier headed first to deliver supplies to Cook in Greenland, where he learned that Peary had set off for the pole from there just a day earlier. Bernier and his crew then sailed more or less directly to Melville Island and secured the ship there for a full year. This was where British explorer William Edward Parry* had overwintered in 1820; the names of his ships and men, etched on what had become known as Parry’s Rock, were still visible.

On 1 July 1909 Bernier and his men gathered at Parry’s Rock and bolted a plaque to it with the following inscription: “This Memorial is Erected today to Commemorate, The taking possession for the ‘DOMINION OF CANADA,’ of the whole ‘ARCTIC ARCHIPELAGO,’ Lying to the north of America, from long. 60° w. to 141° w. up to latitude 90° n. Winter Hbr. Melville Island, C.G.S. Arctic, July 1st 1909. J. E. Bernier, Commander.” No evidence exists that the Laurier government had instructed him to make this sector claim. (Bernier had actually already claimed the entire archipelago three weeks earlier, during a Roman Catholic ceremony attended almost exclusively by the French Canadian members of his crew. The event did not, however, make it into his official report.) The Arctic returned to port in Quebec City on 5 Oct. 1909. When Bernier reported to his superiors, this time the Laurier government endorsed his taking possession of the archipelago, perhaps because his very tangible claim, bolted to a rock, would be difficult to deny. Also, there was likely a realization that Bernier’s unconventional assertion of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic had value since both Cook and Peary had just announced they had reached the pole.

Third Arctic expedition, 1910–11

Bernier considered the period after his 1908–9 voyage to be the high point of his career in Arctic exploration. He was constantly in the press, featured both for his own work and as an authority on the Peary–Cook affair. The government publicly lauded him. It raised his annual salary from $2,400 to $3,000 and gave him, in exchange for a dollar, 960 acres at Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik in Inuktitut) on Baffin Island, which he dubbed “Berniera.” In addition, Laurier promised him support for an expedition to try to reach the pole. But by the time Bernier set sail on the Arctic on 7 July 1910, with a crew of 35, the government’s enthusiasm had waned, and once more the captain was instructed to patrol Arctic waters. There was not even any mention of making territorial claims. By virtue of having asserted possession of the entire sector the previous year, there was really nothing more for Bernier to claim.

After the Arctic’s return to Quebec City on 25 Sept. 1911, two crewmen publicly accused Bernier of having treated the voyage as a private fur-trading trip. It was an allegation that had dogged each of his government-funded expeditions because he encouraged his men to trap and he himself actively traded with the Inuit. He had always deflected such attacks in the past by arguing that trapping kept his crew occupied and trade kept the locals happy. Also, he always made sure to give furs to leading members of the government and civil service. This time an investigation was launched, the third involving him during his government service. He resigned and was replaced as captain of the Arctic.

Voyages and activities, 1912–22

Bernier spent the next decade jumping from one enterprise to another. He purchased the schooner Minnie Maud and took it to Baffin Island in 1912–13 with a small crew to look for minerals and trade in fur. In 1914–15 and 1916–17 he commanded the steamer Guide on northern fur-trading expeditions. On the former voyage, he brought along two German American filmmakers, whose film The land of the midnight sun was one of the first made in the Canadian Arctic. He returned from the latter voyage to learn that Rose, his wife of 46 years, had died.

In 1917 Bernier was hired by the Canadian government to deliver mail along the St Lawrence River, and the next year he was commissioned to take a First World War convoy across the Atlantic. In 1919 he married Alma Lemieux, whom he had met while visiting friends in Ottawa. In late 1921 Bernier and several associates founded the Arctic Exchange and Publishing Company, which in Quebec City that year printed an account of the Minnie Maud voyage. The company’s primary interest, however, was to persuade the new federal government, led by William Lyon Mackenzie King*, to grant it exclusive commercial rights to the Arctic Archipelago in exchange for its occupation of the islands.

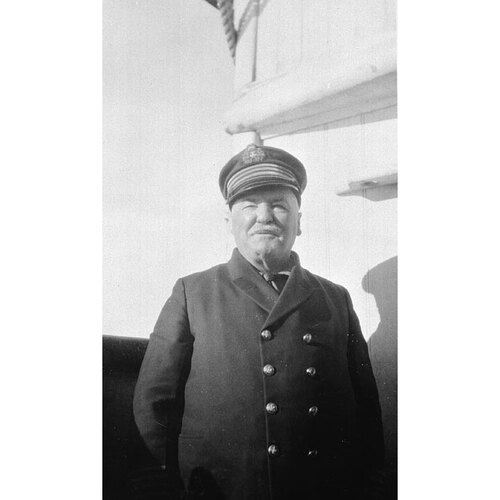

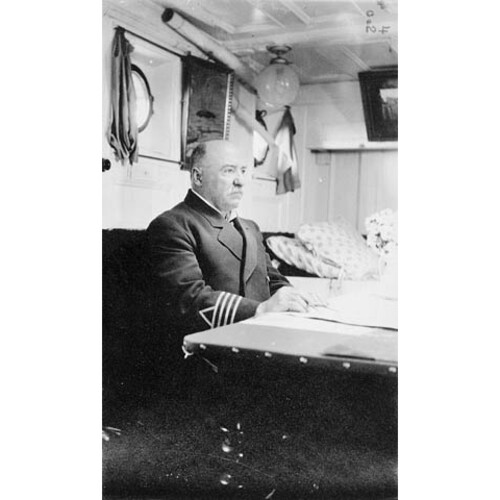

Eastern Arctic Patrol, 1922–25

Although the proposal put forward by Bernier and the Arctic Exchange and Publishing Company to occupy the Arctic was rejected, it nonetheless spurred the federal government to create the Eastern Arctic Patrol in 1922. Its mandate was to uphold Canadian sovereignty in the north by establishing and supplying Royal Canadian Mounted Police posts, conducting scientific work, and providing medical care to the Inuit. And so at the age of 70, Bernier was called upon by the Canadian government to captain the Arctic once more. For a salary of $500 per month, he sailed the ship for three years, under the command of others [see John Davidson Craig], on patrols up Davis Strait and Baffin Bay. In 1924 the Royal Canadian Mounted Police set up a post on Devon Island (Nunavut) and the detachment stationed there was named in Bernier’s honour. Both he and the Arctic were retired from government service once and for all in 1925. In what might have seemed a wistful act, he bought the ship for $4,000 – but then sold it days later to the Hudson’s Bay Company for $9,000. Bernier was forced to return the $5,000 profit when it emerged that the company had believed he was selling it on behalf of the government. The Hudson’s Bay Company removed everything of value from the ship and left the hulk to rot on the Lévis shore near Bernier’s home.

Relations with the Inuit

There can be no doubt that Bernier’s voyages disrupted the lives of the Inuit he met. He and his men brought diseases from which the people of the north had little immunity. They also drastically overhunted fur-bearing animals on which Inuit communities depended. Yet Bernier had great admiration for the Inuit, who called him Kapitaikallak, meaning the “stout little captain.” He respected their capacity for survival in the Arctic, relied on the expertise of their guides, and was open to adopting their methods and technologies for life in the north. In interviews with anthropologist Stéphane Cloutier in the early 2000s, many Inuit elders in Mittimatalik expressed the community’s fond memories of Bernier. Wilfrid Caron – the son of Bernier’s cousin Philomène Caron (Elmina’s brother), and one of his regular crewmen throughout the 1910s – stayed in the hamlet conducting business for Bernier between 1917 and 1920. He formed a relationship there with an Inuk woman named Inuguk Panikpak, and they had three children. Descendants of Caron in Quebec and Nunavut met for the first time in 2001.

Retirement and recognition

In retirement Bernier embarked on a campaign to win recognition and further remuneration for his contributions to Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic. Tramping around wintry Ottawa without a coat – the better to demonstrate his imperviousness to the cold – he hounded the government for a pension, which he was accorded in 1925 at a rate of $2,400 per year. Bernier also received a series of international accolades during this period. He was granted the Back Award by the United Kingdom’s Royal Geographical Society in 1925 and the Imperial Service Medal (for which he had lobbied) two years later. Pope Pius IX met with him in 1933 and made him a knight of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem.

Bernier was less successful in achieving such acclaim within Canada itself. The times were not in his favour. In the 1920s and 1930s officials at the Department of the Interior were advancing a linear version of Arctic sovereignty in which Canada, having been granted the archipelago, was slowly but unwaveringly taking steps for its effective occupation. Bernier’s flag-planting complicated, if not contradicted, this narrative. The ministry downplayed and even distorted what value there had been in his affirmations of sovereignty. In 1930 the director of the North-West Territories and Yukon branch, Oswald Sterling Finnie*, reported to his deputy minister that “there is no record showing that Captain Bernier was ever, at any time, formally commissioned by our Government to claim any areas in the Arctic for Canada” – a statement Finnie surely knew to be untrue. In 1934 Bernier suffered a severe stroke at his Lévis home and died ten days later, without having achieved the prominence or gratitude he believed he deserved.

Legacy

Joseph-Elzéar Bernier’s national and international reputation has become tied to his 1909 sector claim and its advance of the sector principle. Bernier was largely forgotten in the decades following his death but was gradually rediscovered. Regardless of whether his flag-raising constituted legitimate claims of possession, his voyages have come to be seen as valuable in solidifying Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic by their acts of occupation: issuing licences to foreign whalers, collecting customs duties, conducting geographical and scientific research, and simply patrolling northern waters in the nation’s name. More than that, Captain Bernier was increasingly celebrated for having been Canada’s champion during the heyday of polar exploration and for sparking national interest in the Arctic. Many Quebecers remember him as the countryman who represented them in a competition for international glory. In 1961 Bernier was designated by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada as a national historic person. Seven years later his birthplace of L’Islet became home to the Musée Maritime de la Côte-du-Sud, and in 1974 it was dedicated to his memory and rechristened the Musée Maritime Bernier (renamed the Musée Maritime du Québec in 1998). It contains a permanent exhibition devoted to him.

The centennial of the Arctic voyages brought Bernier far greater attention. Even the claims of possessions he had made in the Arctic, including the 1909 sector claim, were re-evaluated, now viewed as important stopgap measures for Canada, keeping other nations at bay until it could demonstrate more permanent acts of sovereignty in the north. It was in this spirit that, during a speech in Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., on 27 Aug. 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper quoted from Bernier’s Melville Island plaque and called the 1908–9 mission “as important to our national destiny in the North as the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway was in the West.” In 2013 an image of Bernier, accompanied by a map of some of his Arctic expeditions, was added to the Canadian passport. The following year the Royal Canadian Geographical Society established a medal in his name. Quebec’s Ministère de la Culture et des Communications named him a person of historical significance in 2016. That same year a life-size bronze statue of Captain Bernier was unveiled at a prominent location on the Lévis waterfront, opposite Quebec City. A concrete acknowledgement such as a monument is no guarantee of historical immortality, of course. But Bernier – who had bolted a record of his expedition’s significance directly onto Parry’s Rock – would have understood that it can help.

There are extensive Joseph-Elzéar Bernier papers at BANQ-Q (P188) and a small collection of relevant records at LAC (R7896-0-0). Notably, the Fonds Joseph-Elzéar Bernier at Le Secteur des Arch. Privées de la Ville de Lévis, Québec (CL01), which has only recently been made available to researchers, contains a copy of the film made during Bernier’s 1914–15 voyage; see reference CL01-S05-SS02-D15 (The land of the midnight sun). Other relevant collections at LAC include: the Department of Marine fonds (R1191-0-0), Northern Affairs Program sous-fonds (R216-186-7), Sir Wilfrid Laurier fonds (R10811-0-X), Nazaire Levasseur fonds (R6758-0-3), John Alexander Simpson fonds (R1642-0-2), and Edward MacDonald fonds (R5217-0-8). In addition, two collections, both titled Fonds Fabien Vanasse, one held at BANQ (P257) and the other at Arch. du Séminaire Saint-Joseph de Trois-Rivières, Québec (FN-0026), are of interest. Other important primary sources are Bernier’s accounts of his voyages: Master mariner and Arctic explorer: a narrative of sixty years at sea from the logs and yarns of Captain J. E. Bernier, f.r.g.s., f.r.e.s. (Ottawa, 1939); Report on the dominion government expedition to Arctic islands and the Hudson Strait on board the C.G.S. “Arctic,” 1906–1907 (Ottawa, 1909); and Report on the Dominion of Canada government expedition to the Arctic islands and Hudson Strait on board the D.G.S. “Arctic,” [1908–09] (Ottawa, 1910). See also Can., Dept. of Marine and Fisheries, Report on the dominion government expedition to the northern waters and Arctic Archipelago of the D.G.S. “Arctic” in 1910, comp. W. W. Stumbles ([Ottawa, 1911]); and Alfred Tremblay, Cruise of the Minnie Maud: Arctic seas and Hudson Bay, 1910–11 and 1912–13, comp. and trans. A. B. Reader (Quebec, 1921).

Major secondary sources are: Janice Cavell, “Sector claims and counter-claims: Joseph Elzéar Bernier, the Canadian government, and Arctic sovereignty, 1898–1934,” Polar Record (Cambridge, Eng.), 50 (2014): 293–310; Yolande Dorion-Robitaille, Captain J. E. Bernier’s contribution to Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic (Ottawa, 1978); Richard Finnie, “Farewell voyages: Bernier and the ‘Arctic,’” Beaver (Winnipeg), summer 1974: 44–54; S. D. Grant, Polar imperative: a history of Arctic sovereignty in North America (Vancouver and Toronto, 2010); Alan MacEachern, “J. E. Bernier’s claims to fame,” Scientia Canadensis (Thornhill, Ont.), 33 (2010), no.2: 43–73; Claude Minotto, “La frontière arctique du Canada: les expéditions de Joseph-Elzéar Bernier, 1895–1925” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1975); S. L. Osborne, “Closing the front door of the Arctic: Capt. Joseph E. Bernier’s role in Canadian Arctic sovereignty” (mj thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 2003); Marjolaine Saint-Pierre, Joseph-Elzéar Bernier: champion of Canadian Arctic sovereignty, 1852–1934, trans. William Barr (Montreal, 2009); and G. W. Smith, A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north: terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939, ed. P. W. Lackenbauer (Calgary, 2014).

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin coll.), 1621–1968,” Notre-Dame-de-Bonsecours (L’Islet), 1er janv. 1852, 8 nov. 1870; Sacré-Coeur (Ottawa), 1er juill. 1919; Saint-Joseph (Lauzon), 26 déc. 1934: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 24 Oct. 2023). LAC, RG85-C-1-A, vol.584, file 571, pt.7 (Dept. of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds, Northern affairs program, Northwest Territories and Yukon branch, Central registry files, Northern Archipelago), O. S. Finnie to W. W. Cory, 28 Nov. 1930 (copy at heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_t13212, image 1520). “Bernier off for the north,” New York Times, 23 Sept. 1904: 9. Stéphane Cloutier, “Ilititaa Bernier, ses hommes et les Inuit: à la rencontre des deux mondes,” L’Aquilon (Yellowknife), 5 oct. 2001 (copy at www.aquilon.nt.ca/Article/A-la-rencontre-des-deux-mondes-17455626162/default.aspx); “Le retour du capitaine Bernier au Nunavut: inauguration de Ilititaa …,” L’Aquilon, 31 mai 2002 (copy at www.aquilon.nt.ca/Article/Inauguration-de-Ilititaa-18431559976/default.aspx). “To take Bank’s Land,” Globe, 27 Aug. 1908: 3. M. A. Bourget, “Un Caron chez les Inuits,” L’Ancêtre (Québec), 29 (2003): 305–9. S. D. Grant, Arctic justice: on trial for murder, Pond Inlet, 1923 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2002).

Cite This Article

Alan MacEachern, “BERNIER, JOSEPH-ELZÉAR (baptized Marie-Joseph-Eléazar),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bernier_joseph_elzear_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bernier_joseph_elzear_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan MacEachern |

| Title of Article: | BERNIER, JOSEPH-ELZÉAR (baptized Marie-Joseph-Eléazar) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |