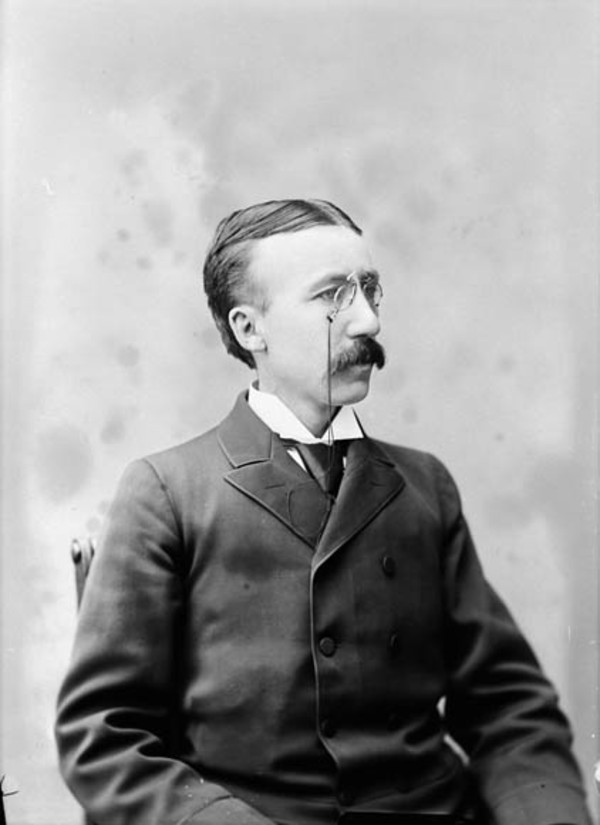

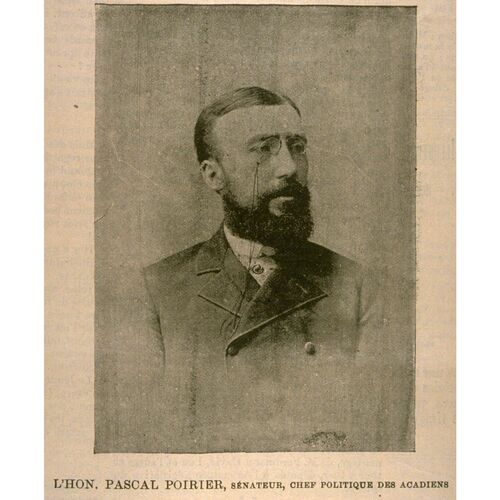

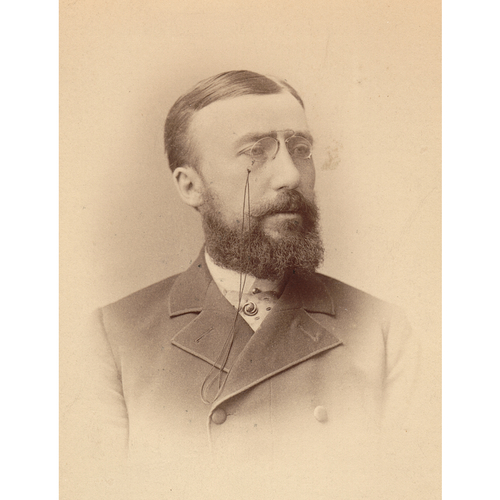

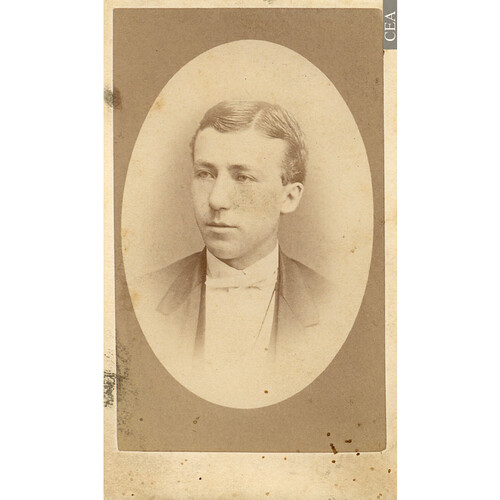

POIRIER, PASCAL, civil servant, author, historian, lawyer, and politician; baptized 16 Feb. 1852 in Grande-Digue, N.B., son of Simon Poirier and Henriette Arsenault; m. first 9 Jan. 1879 Anna-Marie Lusignan (d. 17 Nov. 1913) in the parish of Saint-Jacques, Montreal, and they had one stillborn child; m. secondly 9 Jan. 1917 Mathilde Casgrain in the parish of Sacré-Cœur, Ottawa; no children were born of this marriage; d. 25 Sept. 1933 in Carleton County (Ottawa) and was buried three days later in Shediac, N.B.

The youngest of a family of 12 children, Pascal Poirier grew up in Shediac in southeast New Brunswick. From 1866 to 1872 he pursued classical studies at the College of St Joseph in Memramcook, training that he believed determined the shape of his future. Through the intervention of Camille Lefebvre*, the founder of the college, Poirier became a House of Commons postmaster in Ottawa in 1872. In 1898 he would publish a biography of Father Lefebvre, who had a decisive influence on him. He was called to the bar of the province of Quebec in 1877 and then to the bar of New Brunswick in 1887. For at least a few years he practised law in his native province.

Poirier’s studies coincided with an important period in Acadian history, namely that of the rebirth of the Acadian nation [see Stanislas-Joseph Doucet*; Gilbert-Anselme Girouard*; Marcel-François Richard*], in which he would be one of the principal players. In 1870 and 1880 Poirier developed, under various influences, his interest in the Acadian past. Father Lefebvre strongly encouraged him to write and give lectures on the subject. Like his contemporaries Philéas-Frédéric Bourgeois* and Placide Gaudet*, Poirier was profoundly affected by the work of François-Edme Rameau de Saint-Père, a French sociologist he admired. He began to be known as a historian in 1874, when he published Origine des Acadiens, the first Acadian history written by an Acadian Maritimer. To a certain extent, this book was a response to the research of Rameau de Saint-Père. It contained, however, some contentious points. For example, Poirier tried to convince his readers that, contrary to the claims of Rameau de Saint-Père and, subsequently, the historian Benjamin Sulte*, there had never been intermarriage of members of indigenous communities and Acadians.

During the 1880s Poirier also acknowledged the absence of Acadian representation in the Senate. When a New Brunswick seat became vacant in 1884, he, like other members of the Acadian elite [see Sir Pierre-Amand Landry*], saw an opportunity to remedy the situation. He put pressure on Conservative prime minister Sir John A. Macdonald*, going so far as to write to him. He emphasized the fact that Acadians were expecting to see one of their own appointed senator and reminded him that Conservative candidates had been elected in Acadian ridings. Poirier informed him that if there was no such appointment, Acadians would be extremely disappointed. In 1885 the Macdonald government named Poirier a senator; as such, he would represent Acadia and New Brunswick until his death. Thus Poirier, a Conservative, had the honour of becoming the first Acadian to hold the position. He left his job as postmaster and settled in Shediac.

In general, Poirier was not one of the most prominent senators: he would not leave his mark on the history of the Conservative Party or the Senate. Nevertheless, he did act on various occasions. In 1890 he called for reform of the process for appointing senators. He found it inconceivable that they were not elected democratically and that the provincial legislatures could not take part in selecting them. He proposed a change to the British North America Act whereby a large proportion of senators would be selected by these bodies in the event of a vacancy. Following a rather cool reception, the motion was withdrawn the same year.

Some of Poirier’s actions in the Senate stood out by virtue of their originality. The relationship of human beings to nature was a subject of concern to him. In 1894 he demanded that forestry companies who dumped their sawdust into rivers be held responsible for polluting them. He was also preoccupied with the natural resources of Canada’s far north. He repeatedly recommended (in 1907, for example) that the Canadian Arctic be explored and that some areas of the region be officially appropriated by Canada. As well, he was a member and president of the Mineralogical Society of the University of Ottawa. Several of his writings – such as his Voyage aux Îles-Madeleine – contain their share of geographical and geological description.

Poirier participated in the debate on the issue of francophone schools by taking up the subject in the Senate, notably in 1915, and in the public arena. His stances – sometimes motivated by linguistic concerns such as the threat of assimilation – often led him to recommend that francophones exercise greater restraint; on a few occasions members of the Acadian and French Canadian elites roundly criticized these appeals. In this debate Poirier wished above all for a return to social peace. As opposed to most of his francophone colleagues, in 1917 he supported conscription. In the upper chamber he stated: “But the moment my country is attacked, when everything I hold dear in this world is threatened with destruction, the moment countries I love are also invaded and threatened with destruction, the moment democracy and freedom are at stake, the moment the fate of civilization hangs in the balance, I put aside my declaration of pacificism and to the sounds of the ‘Marseillaise’ I shout: ‘Aux armes citoyens!’”

In 1881 Poirier had taken an active part in organizing and running the first Convention Nationale des Acadiens; he would do the same for the second (1884) and third (1890). In his opinion the Acadians’ lack of unity and their wide dispersal were glaringly obvious. In his memoirs, published in the Cahiers of the Société Historique Acadienne, Poirier wrote: “It was the first time, since the Great Upheaval, that the scattered sections of our race found themselves reunited.… We were children of the same family who did not know each other, strangers to one another. We approached each other with curiosity, and above all with emotion.” His actions were among the most important at these conventions, which were decisive in forming a collective Acadian frame of reference at the end of the 19th century.

One of the main issues at the first Convention Nationale des Acadiens, which was held in Memramcook, was choosing a national holiday. People wavered between the feast of St John the Baptist on 24 June, which would certainly symbolize a rapprochement with French Canada, and the feast of the Assumption on 15 August, which would provide Acadians with a more distinctive identity and nationality. Poirier spoke out in favour of Assumption day, an important stand that clearly reflected a more positive and autonomist idea of Acadian nationalism at the time; the assembly would adopt his recommendation. In his view, despite the obvious affinity between French Canadians and Acadians – he spoke of a “true friendship” between the two groups – Acadia was a nation in its own right, as was French Canada. During the second convention, held in Miscouche, P.E.I., Poirier supported Abbé Marcel-François Richard’s proposal to adopt “Ave maris stella” as the Acadian national anthem.

At the third convention, held in Church Point, N.S., Poirier became the first president of the Société Nationale l’Assomption, an organization dedicated to defending and promoting Acadian national interests. In this role Poirier, working alongside Pierre-Amand Landry, a judge of the Supreme Court of New Brunswick and secretary of the society, devoted considerable effort to the process of appointing the first Acadian bishop in the Maritimes; in 1900 it would be the main subject of discussion at the fourth convention, which took place in Arichat, N.S. However, he had to give up his position as president in 1904 in order not to jeopardize this cause and to maintain the reputation of the organization, particularly before the Roman Catholic clergy. His criticism of the quality of teaching in francophone Catholic colleges, which he had voiced the previous year, did indeed cause some people (notably Bourgeois) to see him as an enemy of the Church. A few years later the Acadian Édouard-Alfred Le Blanc would accede to the episcopate when he became bishop of Saint John in 1912. Poirier was involved in the subsequent conventions. He was very active during the fifth, held in 1905 in Caraquet, N.B., at which one of the major themes was education, an important issue for the senator. At the seventh convention, which took place in Tignish, P.E.I., in 1913 [see François-Joseph Buote*], special mention was made of Poirier’s return as president of the Société Nationale l’Assomption. He would remain president until 1921.

Poirier’s intellectual pursuits broadened as the years passed. Many considered him to be one of the first Acadian historians or one of the first Acadian men of letters. His interests included literature, the theatre, and linguistics, as demonstrated by Le Parler franco-acadien et ses origines, a study published in 1928. His writing also touched on poetry, politics, and geology. Poirier’s literary, historical, and intellectual legacy was unequalled for his time. For Acadia the work of this prominent scholar signalled the beginning of an intellectual culture that was its own. He was a dedicated individual who believed that the advancement of Acadia definitely lay in memory and culture, but also in investment in major institutions: the political world, national societies, the media, and the Catholic Church. Poirier’s life embodied these multiple commitments, and undoubtedly reflected challenges to be taken up by Acadians. In that regard his chosen path differed from those of other leading figures of contemporary Acadian nationalism. Abbé Richard, for example, was certainly one of Acadia’s most ardent defenders, but his actions took place largely within the remit of the Church; as well, in his view Acadian progress lay above all in that institution, in education, and in settlement. In that sense Poirier’s vision was more comprehensive than Richard’s.

Pascal Poirier died in office in 1933 following a coronary thrombosis. In his lifetime the French government made him a chevalier of the Legion of Honour (in 1902) and awarded him the Ordre des Palmes Académiques. The Alliance Française in Paris presented him with a gold medal in 1929. He was a member of various prestigious organizations, including the Royal Society of Canada from 1899. Poirier’s involvement in the Conventions Nationales des Acadiens made him an outstanding symbol of Acadian identity. A civil servant, a senator, and an active figure in public, political, and intellectual arenas, he regularly spoke out about Acadian issues. Poirier personified, perhaps even more so than the nationalist Abbé Richard, the Acadian challenges of his time.

Pascal Poirier is the author of, among other works, the following: Origine des Acadiens (Montréal, 1874); Le père Lefebvre et l’Acadie (Montréal, 1898); Institut canadien-français d’Ottawa: réminiscences (Ottawa, 1908); Des Acadiens déportés à Boston, en 1755: (un épisode du Grand Dérangement) (Ottawa, 1909); Voyage aux Îles-Madeleine (s.l., [1916?]); Le parler franco-acadien et ses origines (Québec, 1928); “Mémoires de Pascal Poirier,” Soc. Hist. Acadienne, Cahiers (Moncton, N.‑B.), 4 (1971–73): 94–135; Causerie memramcookienne, P.‑M. Gérin, édit. (Moncton, 1990); Le glossaire acadien, P.‑M. Gérin, édit. (Moncton, 1993); “Les Acadiens à Philadelphie,” suivi de “Accordailles de Gabriel et d’Évangéline” (Moncton, 1998).

A more complete list of his writings can be found in the following publication: Yolande Doucet, Bibliographie de l’œuvre de Pascal Poirier, premier sénateur acadien, précédée d’une étude biographique ([Montréal, 1941]).

AO, RG 80-8-0-462, no.11308. BANQ-CAM, CE601-S1, 9 janv. 1879. Centre d’Études Acadiennes, Univ. de Moncton, Fonds Pascal-Poirier, 6. FD, Sacré-Cœur (Ottawa), 9 janv. 1917; Visitation (Grande-Digue, N.‑B.), 16 févr. 1852. PANB, RS141C4, F18731, 17 Nov. 1913 (mfm.). Le Devoir, 26, 27 sept. 1933. Le Moniteur acadien (Shédiac, N.‑B.), 1er juill. 1892. BCF, 1930: 486. Gérard Beaulieu, “Pascal Poirier: notes biographiques,” Soc. Hist. Acadienne, Cahiers, 4: 92–93. Can., Senate, Debates, 1890–1917. Conventions Nationales des Acadiens, Recueil des travaux et délibérations des six premières conventions, F.‑J. Robidoux, compil. (Shédiac, 1907). Deborah Robichaud, “Les conventions nationales (1890–1913): la Société nationale l’Assomption et son discours,” Soc. Hist. Acadienne, Cahiers, 12 (1981): 36–58. Léon Thériault, “Acadia from 1763 to 1900: an historical synthesis” in Acadia of the Maritimes: thematic studies from the beginning to the present, ed. Jean Daigle (Moncton, 1993), 45–88.

Cite This Article

Julien Massicotte, “POIRIER, PASCAL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/poirier_pascal_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/poirier_pascal_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Julien Massicotte |

| Title of Article: | POIRIER, PASCAL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 13, 2025 |