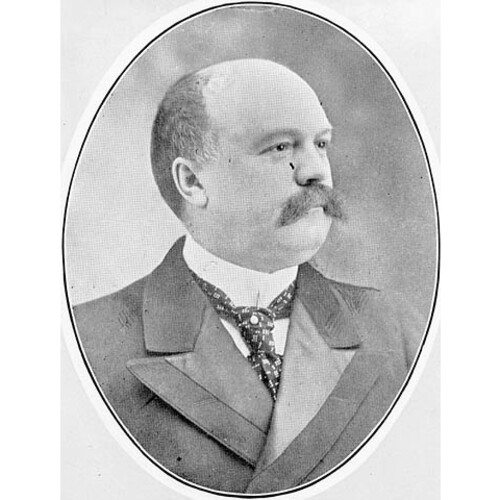

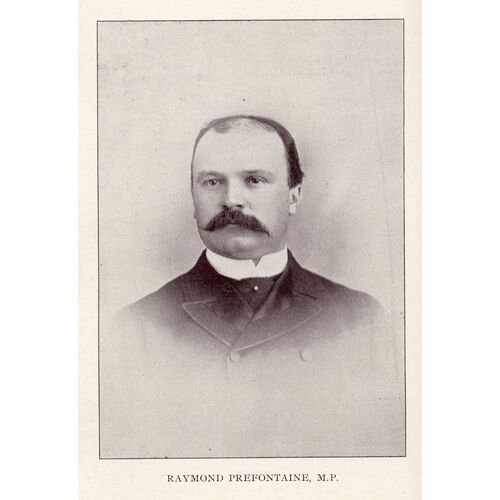

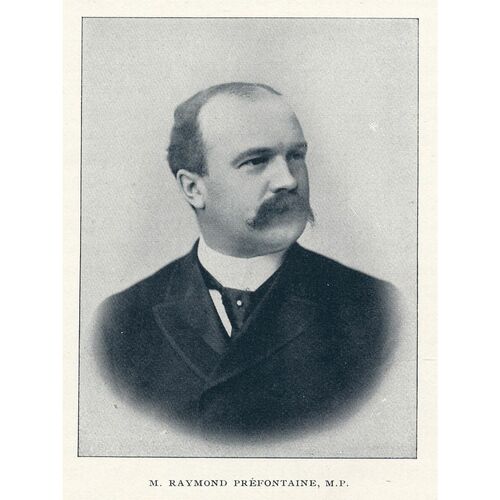

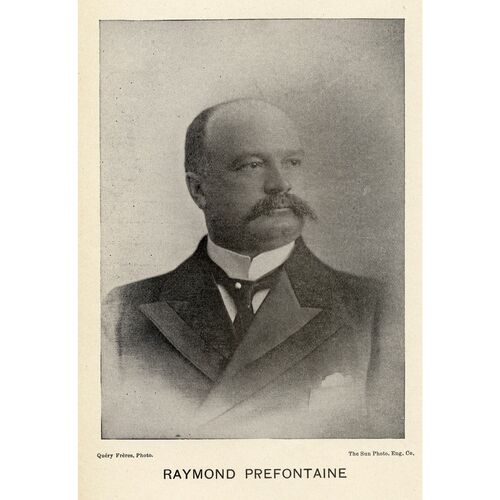

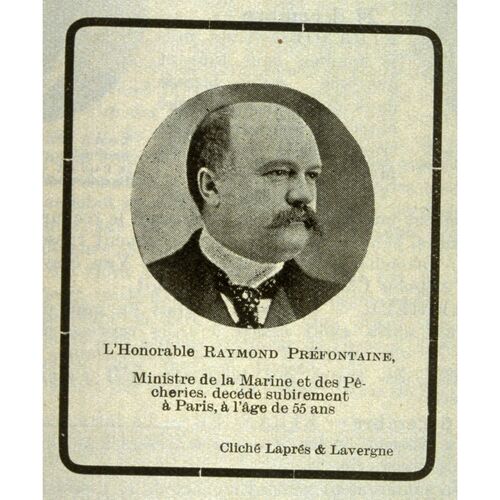

PRÉFONTAINE, RAYMOND, lawyer and politician; b. 16 Sept. 1850 in Longueuil, Lower Canada, son of Toussaint Fournier, dit Préfontaine, and Ursule Lamarre; m. 20 June 1876 Hermantine Rolland, youngest daughter of Jean-Baptiste Rolland* and Esther Boin, in the parish of Saint-Jacques, Montreal, and they had three sons; d. 25 Dec. 1905 in Paris and was buried 25 January in Montreal.

Little is known about Raymond Préfontaine’s childhood except that he lived on the family farm, which was among the larger ones in the Longueuil region. His father owned 264 arpents of land and had two hired men, a servant woman, and sufficient means to give his children an education. After finishing elementary studies in 1863, Préfontaine enrolled in the second year (Syntax) at the Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal. He graduated in 1870 and went on to study at the law faculty of McGill College, where he stood first in Roman law and second in the history of law. He articled in the office of Antoine-Aimé Dorion* and Christophe-Alphonse Geoffrion*, both dyed-in-the-wool Rouges. Geoffrion would later say that Préfontaine was “a good lawyer” but “a mediocre clerk,” because “boring procedural details were not to his liking and he neglected the study of the profession in favour of battles on the hustings.” In July 1873 Préfontaine was called to the bar and joined the firm of John Adams Perkins and Donald Macmaster. He would remain in practice, with a number of other partners, until the end of his life.

Préfontaine was one of the young Liberals who frequented the Club National, that seed-bed of mps and mlas, from the time of its founding in 1875. Political organizers looking for new blood persuaded him to be a candidate in Chambly in the provincial election that year. From then until 1881 he ran four times against the same opponent, Dr Michel-Stanislas Martel. Elected in 1875 and defeated in 1878, he won a by-election in 1879, after the 1878 vote was declared invalid, and lost again in 1881. A good speaker on the hustings, he seemed much less at ease in the Legislative Assembly. He seldom took part in debates, but he listened, gathered information, studied the issues, and, above all, paid close attention to the interests of his constituents.

His marriage in 1876 to the daughter of Jean-Baptiste Rolland gave him an entrée into the world of business and showed him how having municipal power could lever profit from investment in land, the value and income from which depend on the quality of public services and of the environment. The Rolland family were pioneers of Hochelaga. A bookseller and stationer, Jean-Baptiste was also a real estate developer there; his son Jean-Damien had been a municipal councillor since 1872 and served as mayor in 1876. The Rollands were Conservatives and the addition of a Liberal son-in-law could only stimulate the growth of the family business. On 13 Jan. 1879 Préfontaine was elected to the council and, through the influence of the Rolland family, his colleagues chose him as mayor and chairman of the finance committee. Jean-Damien went back to being an ordinary councillor.

Préfontaine continued the policy of development advocated by the Rollands. He had what is now Rue Notre-Dame widened and the streets paved with stone; public services were improved and the streetcar line was extended to the east. He granted tax exemptions to businessmen and industrialists, while ensuring that municipal finances remained sound. Parc Dézéry and a few other areas were beautified. Hochelaga became a lively and charming village. Préfontaine longed for the day when it would be incorporated as a town and annexed to Montreal. This pleasant dream did not appeal to Montreal anglophones, who feared that the annexation of a French-speaking neighbourhood would reduce their weight on the Montreal city council, where they held a majority. It was equally worrying to the residents of Hochelaga, who were suspicious of Montreal imperialism. The negotiations proved difficult, but through successive compromises the parties concerned reached an honourable agreement. On 30 March 1883 Hochelaga was incorporated as a town and within it Hochelaga ward was created and accorded three representatives at city hall; Montreal assumed Hochelaga’s debt, retained its civic employees on the payroll, and undertook to complete the water and sewer systems, maintain a streetcar service, and respect the tax exemptions granted to certain companies. On 23 November a citizens’ meeting unanimously approved the annexation. Préfontaine, Jean-Damien Rolland, and Joseph Gauthier were sworn in as aldermen for Hochelaga ward at Montreal city hall on 21 December; six days later the provincial legislature created the municipality of Maisonneuve from the part of Hochelaga that had not been annexed.

Préfontaine was then 33. Possessed of a quick mind that grasped the overall picture, he was crafty, clever in back-room negotiations, and full of common sense. He was a man of action whose strength, as his friend Laurent-Olivier David* remarked, lay in the “rapidity of his judgement,” his genius for organizing, and his capacity for work. His greatest assets were his relations with the Rolland family, his connections to the Liberal élite, and his rapport with the ordinary people of the east-end wards of Montreal, who responded to his patriotic and sometimes pro-labour rhetoric. This latter asset was one of the most important in a city where the process of annexation was well on the way to creating a predominance of French-speaking Catholics and small wage-earners.

Power games are more complicated in a large city than in a village. Préfontaine had to learn his way around city hall, and that left him time for other ventures. In November 1885, as the representative of a French-speaking ward, he publicly vented the frustration of his constituents following the execution of Louis Riel*. He delivered a stirring address at the Champ-de-Mars rally on 22 November, and then accepted nomination as a candidate in the July 1886 federal by-election for Chambly, which would centre on repudiation of the “hangmen.” After a rousing campaign – his 11th in 11 years – he won the seat by 81 votes and never lost another election.

Sitting in opposition in the House of Commons, Préfontaine was a rather unassuming member, although he was very active in election campaigns. He devoted most of his energy to the municipal scene. The political system in Montreal was unusual in that the mayor was elected annually by property owners and not, as elsewhere, by the aldermen. There was an unwritten rule that the office should go alternately to English-speaking and French-speaking incumbents. In fact, the mayor was simply the chairman of the city council, exposed to the scheming of various factions: he ruled, but did not always govern. Influential men chaired the committees, perhaps the most important being the chairman of the roads committee, who had a budget. With the administrative staff, this alderman established a work plan, which he then had to get passed by a majority in council, and, if possible, accepted by a vigilant public. The office was the one most coveted by political parties, since it played the same role as departments of public works did on the provincial and federal levels: it was a locus for sorting out the interests of the city as a whole and of the wards, as well as for negotiating rebates on fat contracts and arranging the privileges and subsidies granted to corporations. The Liberals under Joseph-Rosaire Thibaudeau, then a senator and the president of the Royal Electric Company, and Honoré Beaugrand, the owner of La Patrie and mayor of Montreal in 1885, were trying to infiltrate some of the committees at the time Préfontaine entered the municipal council. His appointment in 1889 as chairman of the roads committee clearly indicates that they had achieved their objective. During the 1890s Montreal city hall would be controlled by a Liberal triumvirate: Préfontaine on the roads committee, Cléophas Beausoleil, the mp for Berthier, who headed the health committee, and Henri-Benjamin Rainville, the mla for Montreal, Division No.3, who chaired lighting and later finance. As head of the committee with the largest budget and the most jobs to hand out in the new wards, which were predominantly French Canadian and working-class in character, Préfontaine set about building a formidable political machine. He joined forces with the contractors and adopted a populist policy, using winter works projects to keep employment up during the slow season and encouraging development in the east end of Montreal. Most important, he financed the election campaigns of some aldermanic candidates in order to control city council.

As chairman of the roads committee, Préfontaine tried to be the voice both of the east-end and of progress. In fact, he was a product of his own day. He had begun his career in Montreal in a new political context. The French Canadian élites, who had founded the Chambre de Commerce du District de Montréal [see Joseph-Xavier Perrault] in 1886, were beginning to find their place in the sun. The popular press brought out hot issues from the lounges of the Montreal Board of Trade and the back rooms of the Montreal Harbour Commission and held them up for public scrutiny. The political system in the city was beginning to open up and to slip from the hands of the English-speaking élites, the more so since with the abolition of the poll tax in 1887 [see Olivier-David Benoît*], the enfranchisement of women, and the permission given property holders to vote even when in arrears on their taxes, some 17,000 citizens in the east-end wards had gained the vote. Inspired by his vision of a metropolis and supported by public opinion, Préfontaine proceeded systematically to improve the streets and beautify the city, to such effect that within a few years Montreal’s appearance was transformed. Major arteries were paved with blocks of granite or wood or surfaced with asphalt; permanent sidewalks made of material more durable than wood were put in place; tunnels were dug; a system of electric-arc and incandescent lighting was installed; electric streetcar lines were laid down; city squares and parks were beautified.

There was something of the visionary about Préfontaine, as his great adversary, the Montreal Daily Herald, would recognize much later, but this intense activity raised questions. Préfontaine’s relations with Thibaudeau, whom he had joined in founding the Chambly Manufacturing Company in 1888 to harness the rapids in the river, with James Cochrane, who had become rich in the paving business, with Louis-Joseph Forget* of the Montreal Street Railway Company, and with many other entrepreneurs, worried the citizens’ committees and leagues that were springing up, as in other North American cities, to reform municipal administration. The Montreal Board of Trade, which championed property owners, was up in arms against the high level of spending. Then, in 1892, George Washington Stephens, an old hand at municipal politics and spokesman for the wealthy English-speaking wards, turned against the inner circle and the clique in charge at city hall. Stephens’s opposition grew into a reform movement which, despite changes in name, continued to pursue the same objectives and to direct its fire at the same man: Préfontaine. But there were contradictions within this movement. It called for a reduction in the debt, not only to make the city council run public business on a sound basis, but also to put brakes on the works projects already in progress, which plainly benefited the French-speaking citizens of east-end Montreal. Although Préfontaine did not back down, he thought it wiser to curb temporarily his ambitions for the mayoralty.

In 1896 Préfontaine also let Richard Wilson-Smith, an anglophone of Irish origins, be elected mayor by acclamation, hoping that the gesture would be reciprocated. In the meantime he ran as a federal candidate in Maisonneuve, which had just been created from the former riding of Hochelaga. Re-elected to the House of Commons, still chair of the roads committee at Montreal city hall, an influential adviser within the Liberal party, a director of numerous companies, and principal in one of the major law firms in Montreal, Préfontaine was well placed to seize the opportunities arising from Wilfrid Laurier*’s election victory. The appointment of Joseph-Israël Tarte as minister of public works – an office befitting Préfontaine’s ambition – was only an incidental irritant.

His acclamation to the mayoralty on 1 Feb. 1898 gave him a new lease on life. But he did not take up the office with the same energy as he had his aldermanship. In giving him prestige and a seat on the Montreal Harbour Commission, which undertook large-scale works projects, the position seemed a springboard to a cabinet career in Ottawa. At odds with the reformers, who held several seats on council, Préfontaine put up a poor defence. All through the winter of 1897–98 they were uncovering scandals and in the fall they launched a number of public inquiries, forcing him to agree to a commission for the review of administration and taxation. The recommendations of the commissioners, half of whom were reformers and half Préfontaine supporters, were accepted in part by the provincial legislature on 10 March 1899. A new charter introduced a more modern form of government. It divided the city into 17 wards instead of 12, each represented by two aldermen. The mayor held considerable power: to supervise the departments, ensure that regulations were observed, submit to council all proposals for the better management of municipal affairs, and suspend any city employee. From then on the mayor was the chairman and the chief executive officer. The council functioned through committees and met at least monthly. In fact, the municipality enjoyed a large measure of autonomy, although the lieutenant governor could issue an order in council disallowing any regulation within three months and the city’s power to borrow money and levy taxes was restricted. The council had all the features of a local legislature: voters, legislative and executive councils, and a bureaucracy under municipal authority, with the mayor as the first officer.

Préfontaine was re-elected mayor in 1900, even though his electoral machine had been severely shaken by the wave of scandals. He was clever enough to ignore the accusations during his campaign and to argue for the development of the harbour in east-end Montreal. He was still the boss at city hall, but his influence within council was more limited. There were 16 reformers on council, some of whom chaired important committees, and his friends Beausoleil and Rainville were no longer there. Although he still had enough influence in 1901 to push through a merger, engineered by Louis-Joseph Forget, of Royal Electric and the Montreal Gas Company into the Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company, his opponents nevertheless continued to multiply. Apart from Tarte, La Patrie, and the reformers, their ranks included La Presse, which took up a populist stance, and the English-speaking voters who supported the rule of alternate French and English mayors. Rather than risk defeat, he declined to run in the election of 1 Feb. 1902.

He did not remain inactive for long. When Tarte resigned from the cabinet as minister of public works in October 1902, Laurier, under pressure from Montrealers, gave Préfontaine the portfolio of marine and fisheries and, for the same reason, transferred to it from public works “the major services relating to navigation.” The new minister, while maintaining his predecessor’s policy, tackled his duties with dynamic energy. He approved experiments in winter navigation and a program for installing illuminated buoys in the channel of the St Lawrence. He appointed a commissioner to preside over all inquiries into marine disasters, in place of the harbour commissioners. He sent Captain Joseph-Elzéar Bernier* to explore the Arctic in order to strengthen Canada’s rights in this region. In 1905 he went to Great Britain and France, one of his goals being to promote a sea link between Marseilles and Montreal. He was in Paris when he was struck down by angina pectoris on 25 December. The French government held his funeral in the church of La Madeleine and a British battleship brought his remains back to Halifax.

Raymond Préfontaine’s career sheds light on certain novel features of Montreal’s progress. Its urbanization took place within a two-headed state in which the church was responsible for social development, and in which there was an urban network of competing towns and villages, a population sensitive to religious and ethnic divisions, and a middle class amenable to state intervention. In this context the lack of enthusiasm shown by the aldermen for having the municipality take on social problems is understandable. City government was rather an instrument in the hands of the local élites to ensure the growth of capital and to attract immigrants. As many historians and geographers have pointed out, the élites used municipal taxation to put in place the infrastructures increasing the value of real estate, to grant bonuses or tax exemptions as a means of attracting merchants and industrialists, to beautify the city and make it appealing, and to bestow privileges or favours on firms that would provide public services. With a suffrage based on property qualifications, and no clear distinction between executive, legislative, and administrative branches, the system of municipal government led to confusion between political and economic power and to an apparent reconciliation of the interests of both through mediation by political leaders who came from the liberal professions or business circles. Préfontaine played the mediator’s role quite effectively, with his political skill and the help of patronage. Unquestionably he was one of those who set Montreal on the path of modernization.

AC, Montréal, État civil, Catholiques, Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (Montréal), 25 janv. 1906. ANQ-M, CE1-12, 17 sept. 1850; CE1-33, 20 juin 1876. ANQ-Q, E53/83; P-174/2. ASJCF, Collège Sainte-Marie, liste des anciens élèves. AVM, D016.758; D026.25. NA, MG 26, G: 19965–66, 59272–83, 59996, 80814–16, 86190, 88845–46, 88912–15, 93884–88; RG 31, C1, 1861, 1871, Longueuil, Chambly county, census dist.2. La Minerve, 24 nov., 22 déc. 1883; 21 févr. 1893. La Patrie, 15 août, 1er sept. 1898; 14, 21 juin 1942. La Presse, 20, 23 nov. 1885; 2 févr. 1898; 26–28 déc. 1905; 4, 25 janv. 1906. Le Soleil, 2 janv. 1906.

The book of Montreal, a souvenir of Canada’s commercial metropolis, ed. E. J. Chambers (Montreal, 1903). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1887–88, 1897, 1899, 1904; Dept. of Marine and Fisheries, Annual report (Ottawa), 1902–5; Statutes, 1890, cc.45, 82; 1892, c.2. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Hélène Chaput, Histoire de la congrégation des Sœurs de SS. NN. de Jésus et de Marie; mère Marie-du-Rosaire . . . (Saint-Boniface, Man., 1892). Directory, Montreal, 1870–1905. Dominion annual reg., 1886. Michel Gauvin, “The municipal reform movement in Montreal, 1886–1914” (ma thesis, Univ. of Ottawa, 1972); “The reformer and the machine: Montreal civic politics from Raymond Préfontaine to Médéric Martin,” JCS, 13 (1978–79), no.2: 16–26. Anne Germain, “Mouvements sociaux de réforme urbaine à Montréal, de 1880 à 1920” (thèse de phd, univ. de Montréal, 1980). Lamothe, Hist. de Montréal. Linteau, Hist. de Montréal. McGill Univ., Annual calendar (Montreal), 1873–74. Man., Statutes, 1895, c.53. Qué., Assemblée Législative, Débats, 1875–78; Statuts, 1875, c.29; 1876, c.70; 1883, c.82; 1884, c.60; 1888, c.73; 1893, c.9; 1899, c.58; 1901, c.66. Quebec Official Gazette, 1883. Robert Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vol.1; Histoire de Longueuil (Longueuil, Qué., 1974); Hist. de Montréal, vol.3. D. J. Russell, “H. B. Ames as municipal reformer” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., 1972). [Télesphore Saint-Pierre], Histoire du commerce canadien-français de Montréal, 1535–1893 (Montréal, 1894). Vieux-Rouge [P.-A.-J. Voyer], Les contemporains: série de biographies des hommes du jour (2v., Montréal, 1898–99), 1.

Cite This Article

Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, “PRÉFONTAINE, RAYMOND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/prefontaine_raymond_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/prefontaine_raymond_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | PRÉFONTAINE, RAYMOND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |

![M. Raymond Préfontaine, M. P [image fixe] Original title: M. Raymond Préfontaine, M. P [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.3317.jpg)