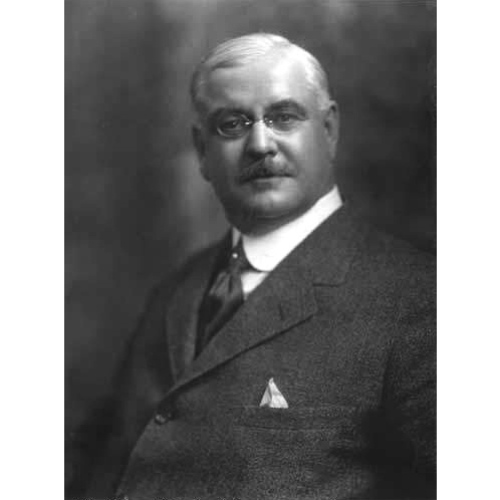

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PERRON, JOSEPH-LÉONIDE, lawyer and politician; b. 24 Sept. 1872 in Saint-Marc, Que., on the Richelieu, son of Léon Perron, a farmer, and Marie-Anne-Eugénie Ducharme; m. 6 June 1898 Berthe Brunet in Montreal, and they had two sons; d. 20 Nov. 1930 in Montreal and was buried 22 November in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery there.

Joseph-Léonide Perron studied at Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir in Marieville. He then enrolled at the Montreal branch of the Université Laval to study law, obtaining his llb in 1892 and his llm in 1895. On 9 July 1895 he was called to the bar of the province of Quebec. He would be made a kc in 1903 and bâtonnier of the Montreal bar for 1922–23.

Perron quickly became one of the most respected lawyers in Montreal. His first partnership, with Raymond Préfontaine*, launched his career and enabled him to attract the attention of influential members of the Liberal party. His next partner was Robert Taschereau, a close relative of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*, who would be a Liberal premier of Quebec. He also lent his name to organizations and causes that would help him become known. In 1903 he became the promoter of the Compagnie de Publication du Canada in Montreal. He was a member of the council of the Montreal Bar Association in 1907. Two years later, along with fellow lawyers Napoléon-Kemner Laflamme and Eugene Lafleur, he appeared for the citizens’ committee before the royal commission that was set up to make a general and complete inquiry into the administration of the affairs of the city of Montreal [see Lawrence John Cannon]. That year, Premier Sir Lomer Gouin appointed him to the Catholic committee of the Council of Public Instruction, thereby causing a stir within the organization in view of the suspicions of anticlericalism that hung over him. He would remain a member for the rest of his life.

At Gouin’s instigation, Perron ran as the Liberal candidate in a provincial by-election in the constituency of Gaspé in 1910. The seat, which had become vacant when Louis-Joseph Lemieux resigned, was seen as a safe one for getting a strong candidate into parliament. The premier wanted to have a progressive Liberal in the Legislative Assembly to oppose Henri Bourassa* and the Conservatives. Thanks to the popularity of the Gouin government, which promised to build a railway in the Gaspé region, Perron won on 17 February in a riding he hardly knew. For unknown reasons he would not run in the general election of 15 May 1912, but he would be elected by acclamation in the riding of Verchères – his birthplace – in a by-election on 16 October.

In the Legislative Assembly Perron learned to carry out his role as a representative of the Liberal party. In 1911 he supported a bill introduced by Godfroy Langlois to grant the Montreal Tramways Company a monopoly of public transportation on the island. Given his professional activities, Perron became the spokesman of the big companies, in particular the Shawinigan Water and Power Company, the Canada Cement Company, and the Excelsior Life Insurance Company.

Perron was soon an important cog in the Liberal machine, especially for the Montreal region. President since 1914 of the prestigious Montreal Reform Club (where the city’s Liberals traditionally met), he increasingly participated in making political decisions concerning the city. This was probably why Gouin on 13 April 1916 appointed him the legislative councillor for the division of Montarville; Perron could now give his full attention to organizing the Liberal campaign in the important metropolitan region. In 1917, when Montreal once again found itself deeply in debt, Perron finalized the plan for recovery imposed by the provincial government: amendments to the city’s constitution, the annexation of Maisonneuve, and the settlement of the street railway question (in which Perron, as lawyer for the Montreal Tramways Company, was both judge and judged). Despite Mayor Médéric Martin*, whose influence was growing, Perron’s vision of Montreal carried the day.

Perron was thus an important figure in the Liberal party. When Gouin retired from provincial politics in 1920, it was only natural that at 47 years of age he should become, along with the attorney general, Louis-Alexandre Taschereau, and the minister of agriculture, Joseph-Édouard Caron, one of the leading candidates to succeed him. Gouin’s choice fell on Taschereau, with whom Perron apparently was not on good terms. The two men would have to learn to work together, however. When Taschereau formed his cabinet on 9 July 1920, Perron became minister without portfolio, unofficially responsible for representing Montreal and large corporations. Although he was the only new member in the cabinet, his strong personality, energy, fine personal qualities, and relations with Taschereau gave promise of a prominent career.

Yet the team seemed to work efficiently. Perron even helped Taschereau to draft the bill passed in 1921 that created the Quebec Liquor Commission. When Joseph-Adolphe Tessier, the minister of roads, was appointed chairman of the Quebec Streams Commission, Perron appeared to be the logical candidate for the vacant post. Already in the cabinet, although without a portfolio, he was seen as the next in line for an important ministry. On 27 Sept. 1921 he became government leader in the Legislative Council and minister of roads. Perron’s appointment to this department, which he would leave in 1929, was undoubtedly the high point of his career, and he carried out projects whose lasting importance would greatly enhance his reputation. At the banquet celebrating his appointment, the new minister announced that he intended to build the sections of highways needed to complete the routes from Lévis eastwards to Gaspé and westwards to Saint-Lambert. He also wanted to link Montreal with Sherbrooke to the south, Mont-Laurier to the north, and Ottawa, by way of Hull. This announcement would not only bring contributions to the party coffers – from contractors eager to benefit from this manna from heaven – but would win votes in the regions concerned, proof of Perron’s talents as an organizer. In 1922 he announced that responsibility for the major highways would pass from the municipalities to the Department of Roads. He then proceeded to categorize the highways designated as provincial, raised taxes on heavy trucks, and introduced a program of maintenance, repair, and construction. In Perron’s view, the new highways were not only useful means for travel, but also attractions for tourists.

Perron’s position as a lawyer for large corporations hurt him occasionally. In the 1923 general election the Conservatives would accuse him of corruption because he was both minister of roads and a director of the Canada Cement Company, one of his department’s suppliers. Nevertheless he was able to use his ministerial functions to make electoral gains. In 1922, for example, he followed Arthur Sauvé*, the leader of the opposition, in order to promise roads wherever the latter was scoring points. Perron used another strategy at meetings. The Liberal mla of a constituency would claim that the future of his region depended on having a highway and make a request to this effect, addressed to the minister, who would be in the audience. After pretending to think deeply about the question, Perron would stand up and announce that the highway would be built.

But Perron was more than just a skilful actor and electoral manipulator; he also kept his promises. In 1925, for example, he reduced the rate of interest on loans to municipalities for road work from 3 per cent to 2 per cent, a reduction the Conservatives had long been demanding. In the same year he decided that responsibility for colonization roads would be transferred from the Department of Colonization, Mines, and Fisheries to the Department of Roads. He was then in a position to begin his work in the Gaspé region: repairs to the highway between Rimouski and Sainte-Anne-des-Monts, and construction of a road around the Gaspé peninsula from Sainte-Anne-des-Monts to Matapédia, for a total of 190 miles in 1927 and 1928. The number of tourists visiting the Gaspé soared from about 100 in 1927 to 3,500 in 1928. The region finally had a road suitable for motor vehicles and a link to the rest of the province in Highway 126, which for a long time was known as Boulevard Perron (now Highway 132). Elsewhere in the province, the highway between Quebec and La Malbaie had been opened in 1925, and Highway 11 (Route des Laurentides) had been extended the following year from Sainte-Agathe to Mont-Laurier. Always drawn to large-scale projects, Perron even considered instituting a monopoly on the sale of gasoline, which would generate significant revenue for the province at a time when automobiles and foreign tourism were on the increase. He gave up the idea under pressure from industry.

Perron never lost sight of his other duties within the cabinet, including that of political organizer for the Montreal region, a task in which he was assisted by Irénée Vautrin and Fernand Rinfret*. With Taschereau on holiday, it fell to Perron to find the reason for the Liberals’ poor performance in the 1923 general election, when they lost ten seats and obtained nearly 15 per cent less of the votes cast than they had in 1919. Refusing to see the party’s real organizational problems, he privately blamed, among others, the chair of the Quebec Liquor Commission, who had not allowed ministers to use the organization to buy votes. Commissioned by the premier, in the spring of 1927 Perron relieved the mayor of Montreal, Médéric Martin, of responsibility for the Liberal forces in the constituency of Montréal–Sainte-Marie. In order to avoid a repetition in 1927 of the failures of 1923, Taschereau gave Perron full authority over the political organization of Montreal. In charge of nominations and patronage, he got rid of independent and dissident Liberals, and he succeeded in improving the election results.

Early in 1929, after nearly 20 years as minister of agriculture, Joseph-Édouard Caron left the cabinet and took over the post of vice-chairman of the Quebec Liquor Commission. Many people believed that the time had now come to provide new impetus to agriculture and Taschereau handed this task – to the surprise of many, considering his excellent work in the Department of Roads – to Perron, his most reform-minded minister. Upon taking office, the minister proposed to put in place a program of agricultural self-sufficiency by encouraging the use of new methods of production and marketing, the establishment of agricultural cooperatives, the electrification of the countryside, and the export of produce. He also transformed the Coopérative Fédérée de Québec into a genuine marketing and exporting organization on a provincial scale, endeavouring to raise agriculture from the level of subsistence farming to that of an industry. The disciples of modernization were enthusiastic when Perron arrived on the scene. Through his dynamism, he wanted to set Quebec agriculture on the path taken by the world leaders.

To justify his new cabinet post, Perron decided to leave behind the placid discussions of the Legislative Council. On 16 Nov. 1929 he was elected mla for the constituency of Montcalm. The limp response of many Liberals to the attacks of some Conservatives was no doubt the real reason for his return to the Legislative Assembly. Taschereau gave Perron the task of standing up to Camillien Houde*, a fiery Conservative and the new mayor of Montreal, who, since his re-election as mla for Montréal–Sainte-Marie in 1928, never missed a chance to criticize the government, and especially Perron.

For Perron, 1930 opened on a promising note. First of all, it was in this year that the plans for the Montreal Harbour Bridge (which would become the Pont Jacques-Cartier in 1934) were changed so that access to it would be across property that he reportedly had just bought. But, above all, Perron was preparing to challenge Taschereau, who in the opinion of many had become too conservative for the leadership. He had his eye on nothing less than the office of premier. To this end, he is said to have even taken unofficial control of some of the party’s organs. Within the party, he stood ready to attack Taschereau, with whom his relations were always strained. His supporters were eager to see the struggle begin, and the press was waiting for the signal to start. Then, without notice, Perron went on holiday in the United States. He had suffered an attack of angina pectoris and had just learned from his doctors that his days were numbered. Without letting his family know how serious his condition was, he went quietly back to the ranks and continued his work in his department, as if nothing had happened. He died on 20 Nov. 1930 at the age of 58, at the height of his career.

In Joseph-Léonide Perron, the Liberal party had a supporter and minister whose dynamism, energy, firm opinions, and fighting spirit brought significant reforms to his departments. As the person responsible for the important Montreal region, he was one of the most influential organizers, probably second only to the premier himself. His work on the provincial highway system and his reforms in Quebec agriculture made him one of the most important ministers in Taschereau’s government.

No collection of papers exists for Joseph-Léonide Perron, and archival repositories tell us little about him. There is, however, some information to be found at the NA, in MG 26, G and at MG 27, III, B4 (Lomer Gouin fonds), and at the ANQ, in the Fonds Louis-Alexandre Taschereau (P350). Historical studies of this period in Quebec’s past are very useful, in particular B. L. Vigod, Quebec before Duplessis: the political career of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau (Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1986), and Conrad Black, Duplessis, (Toronto, 1977). Robert Lévesque et Robert Migner, Camillien et les années vingt, suivi de Camillien au goulag: cartographie du houdisme (Montréal, 1978), shows the animosity that existed between Camillien Houde and Perron when the latter had to return to the Legislative Assembly. More indirectly, Jules Bélanger et al., Histoire de la Gaspésie (Montréal, 1981), and J.-G. Genest, Godbout (Sillery, Qué., 1996), furnish a number of details as does the reliable Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec.

ANQ-M, CE601-S1, 6 juin 1898; S46, 25 sept. 1872. Le Devoir, 20 nov. 1930. Le Soleil, 4 févr. 1921. DPQ. P. [A.] Dutil, Devil’s advocate: Godfroy Langlois and the politics of liberal progressivism in Laurier’s Quebec (Montreal, 1994). Hector Grenon, Camillien Houde, raconté par Hector Grenon ([Montréal], 1979). Hertel La Roque, Camillien Houde, le p’tit gars de Ste-Marie (Montréal, 1961). Charles Renaud, L’imprévisible monsieur Houde (Montréal, 1964).

Cite This Article

René Castonguay, “PERRON, JOSEPH-LÉONIDE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/perron_joseph_leonide_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/perron_joseph_leonide_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | René Castonguay |

| Title of Article: | PERRON, JOSEPH-LÉONIDE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 27, 2025 |