Source: Link

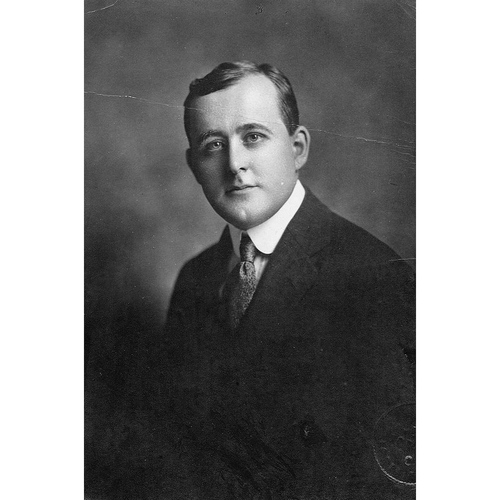

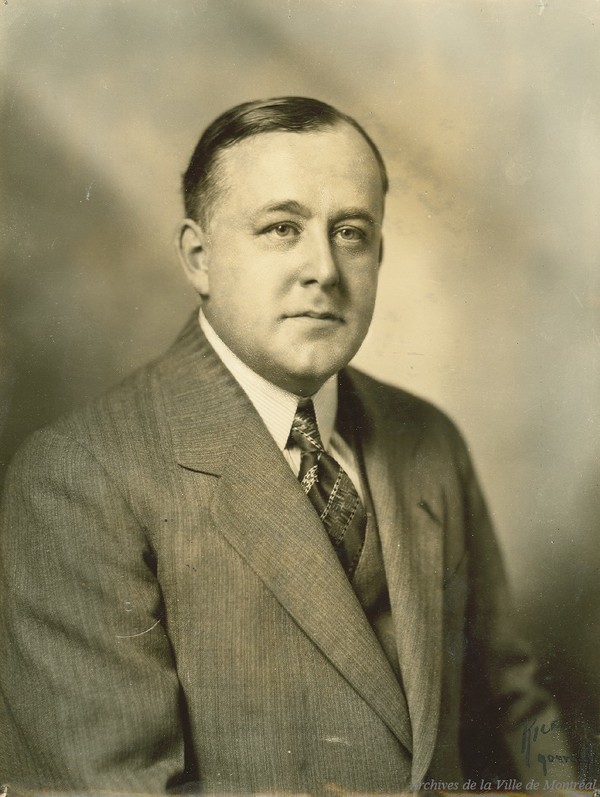

RINFRET, FERNAND (baptized Louis-Édouard-Fernand), journalist, author, editor, politician, and teacher; b. 28 Feb. 1883 in the parish of Saint-Jacques (Montreal), son of François-Olivier Rinfret, a lawyer, and Marie-Julie-Albina (Albina) Pominville; m. 4 June 1908 Berthe Lemoyne de Martigny in Ottawa; they had no children; they separated in December 1912; d. 12 July 1939 in Los Angeles and was buried eight days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery in Montreal.

Very little is known about Fernand Rinfret’s childhood, save that he was born into a seemingly well-to-do Montreal family. His father, François-Olivier Rinfret, died in 1885 when his three sons were very young. His mother, Marie-Julie-Albina Pominville, remarried in 1892; her second husband, Arthur Gagnon, was a bank inspector and auditor. The eldest boy, Thibaudeau*, followed in his father’s footsteps and pursued a career in law. From 1924 he sat on the Supreme Court of Canada, where he was chief justice from 1944 to 1954. The other brother, Charles, worked in the watch- and clock-making industry in the Montreal area. As for young Fernand, he began his studies at the Collège Notre-Dame in Côte-des-Neiges (Montreal) and continued at the Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal, where he earned a baccalauréat ès arts in 1900. During those years he discovered a passion for literature, music, and the arts, which he would maintain all his life.

In June 1908 Rinfret married Berthe Lemoyne de Martigny; their marriage contract was never registered, however, which would later become problematic for settling the estate. The couple separated in December 1912. On 14 Nov. 1939, shortly after Rinfret’s death, Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* would note in his personal diary that Berthe had told him she had “been responsible for the separation from Rinfret by running away with some other man and marrying in the States.”

After his studies Rinfret became assistant secretary to Raymond Préfontaine*, a former mayor of Montreal, a Liberal organizer, and the minister of marine and fisheries in the cabinet of Liberal Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*. These initial contacts linked him closely to the party. At the beginning of the 20th century Rinfret turned his attention to journalism. He first spent some time working for the Liberal newspaper L’Avenir du Nord of Saint-Jérôme, where he wrote literary and political articles in support of the party, sometimes under the pseudonym Paul Destrée (over the course of his career, he would also use Graindorge and Pierre Simon). He compiled some of the articles in two critical studies on French Canadian poets, published in 1906 in Saint-Jérôme: the first on Octave Crémazie* (Études sur la littérature canadienne-française : première série, les poètes : Octave Crémazie) and the second on Louis Fréchette* (Louis Fréchette). Rinfret was recognized for his literary abilities: he was elected a member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1920, in the section devoted to history, archaeology, sociology, and French literature; named a chevalier of the Legion of Honour in December 1925; and granted an honorary doctor of letters degree from the Université Laval in 1937.

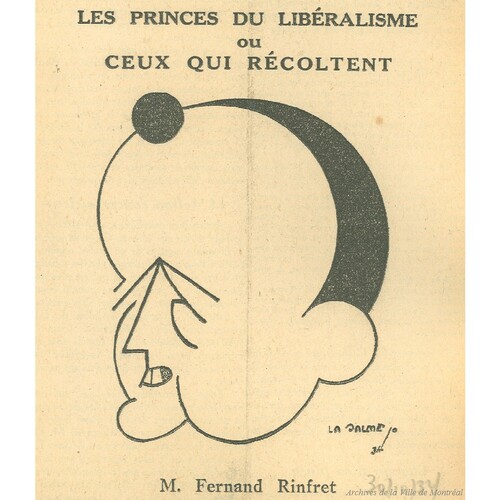

Rinfret became a parliamentary correspondent for Le Canada in 1907. This Montreal daily, founded in 1903, was the Liberal Party’s francophone organ. He was promoted to editor in chief in 1909, succeeding Godfroy Langlois*, who had been dismissed for no longer toeing the party line. In contrast, the new editor would be irreproachable. On 15 Sept. 1914 Laurier, the opposition leader at that time, instructed him to respond to editorials written by the editor of Le Devoir, Henri Bourassa*, regarding the circumstances leading up to World War I and Canadian participation in the conflict. Rinfret wrote: “[W]e wish to give the events and writings what we believe to be their true meaning. And this makes us increasingly desirous of clearing up any misunderstanding in the minds of our English compatriots concerning French Canadian sentiment and the inviolable commitment, beyond the slightest ulterior motive, which the mother country has found in us on the threshold of this war.” Rinfret visited England and the front in France in 1918 with a delegation of Canadian journalists. He shared his impressions in the pages of Le Canada and in a pamphlet entitled Un voyage en Angleterre et au front français. In March 1919 he wrote a series of articles for Le Canada, which he then had published as a pamphlet called Le Libéralisme de Laurier, on the career of the politician who “sought the advancement of his country all his life: through tolerance; through conciliation among the various parts which make up our country; through respect for the beliefs of all; through the perfect autonomy of Canada within the empire; through the sovereign freedom of the popular vote.” Rinfret’s time as editor of Le Canada came to an end in 1926; it had marked a period of flexibility and moderation compared with the tone set by his predecessor Langlois and by Olivar Asselin, who would take over four years after he left. Passionate about journalism, Rinfret also turned to teaching the profession at the Université de Montréal, where he became an instructor in 1921.

Rinfret belonged to the Montreal Reform Club, whose aim was to support the Liberal Party of Canada, and he was its president in 1916–17. He was honorary president of the Société Canadienne d’Opérette Incorporée and a member of the Club Saint-Denis, the Cercle Universitaire de Montréal, the Alliance Française in Ottawa, and the Montreal Library commission (1917–20). As well he was a director of the Institut Bruchési, which provided treatment for tuberculosis. An amateur sportsman, by the early 1930s he was serving as a director of the Canadiens hockey club, whose president was Louis-Athanase David*, secretary of the province of Quebec. Rinfret was a lifetime member of the Association Athlétique d’Amateurs Nationale [see Raoul Dumouchel] and the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association.

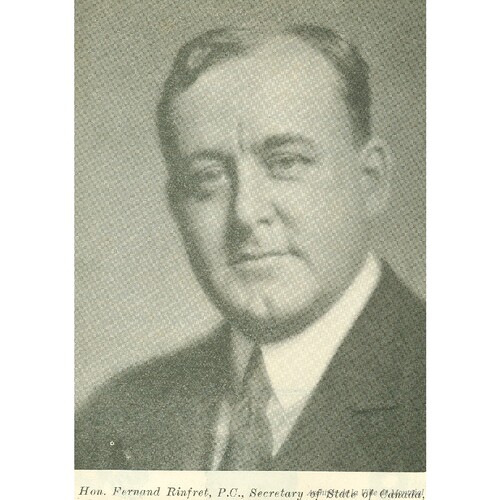

Rinfret was elected for the first time in the federal riding of Saint-Jacques in the by-election of 7 April 1920, following the death of Liberal mp Louis Audet-Lapointe. The Liberals, who held a majority in the province of Quebec, formed the opposition in the House of Commons. Rinfret would represent the same constituency as a Liberal until his death in 1939. In 1926 he accepted the position of secretary of state of Canada, offered to him by Prime Minister King. In his diary entry for 22 September King indicated that he appointed Rinfret to the post because “it was the Department for someone of literary tastes and abilities.” King soon expressed disappointment in his recruit, however, without much explanation. He recognized Rinfret’s great qualities as an orator who expressed himself well in both languages and praised his speeches several times, but he worried about his bad habits, which in his opinion were destroying him physically. Rinfret held the post until Richard Bedford Bennett*’s Conservatives came to power in 1930. Even though he appeared less frequently in the House of Commons while a member of the opposition, he delivered a few good speeches, notably when he attacked the government “without gloves,” as King reported on 18 June 1931, for adding to the fiscal burden on taxpayers while simultaneously easing it for Bennett and other millionaires.

A term as mayor of Montreal, from 1932 to 1934, contributed to Rinfret’s absences from the chamber. His contacts in the Liberal Party machine, especially with the premier of the province of Quebec, Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*, had prompted him to stand as a candidate for the office, which he sought with the aim of replacing Camillien Houde*, then the leader of a metropolis mired in a deep financial crisis, and of opposing the St Lawrence canalization project. On 4 April 1932 Rinfret became mayor with a majority of over 12,000 votes. During his brief mandate he remained in the background, leaving most of the work to municipal councillors and dealing only with tasks related to protocol and representation. He was simply not able to provide solutions to the citizens of Montreal, who were badly affected by the financial crisis. He did not run for election in 1934; Houde won by more than 50,000 votes over his closest rival, Anatole Plante, whose candidacy had been encouraged by the provincial Liberal Party.

The following year King and his troops again formed the new government in Ottawa. Having considered other options, including offering the post of secretary of state to Pierre-Joseph-Arthur Cardin*, the member for Richelieu-Verchères, King offered it once more to Rinfret. In his diary he explained his move: although he felt that Rinfret had not met expectations as a minister, he had to keep him in his cabinet to balance the delegations from Ontario and the province of Quebec, and also because of the man’s influence in Montreal. Once again King seemed disappointed by Rinfret’s performance; he also expressed regret, on several occasions, about his bad habits and worried about his health. After Rinfret’s death he would write: “Rinfret’s career, in many ways had been a truly remarkable one. His gift of writing and speaking, and a very pleasing personality, gave him the power he had. The tragedy is that he allowed these talents to be wasted. Had he lived the life he should have, he might have had 20 years ahead and an exceptional place in the public life of our country.”

On 12 July 1939, while on a restorative trip in Los Angeles, Rinfret died of a heart attack. His remains were repatriated to Montreal by train. Because he was a public figure who had died in office, the newspapers called for a state funeral, which did not transpire. Nevertheless, a huge crowd gathered on 20 July for the requiem mass at the cathedral of Saint-Jacques in Montreal and for the funeral procession to the cemetery. Several cabinet ministers, federal and provincial members of parliament, bishops, consuls, senators, judges, dignitaries, mayors, municipal councillors, prominent individuals, senior civil servants, and other official delegates came to pay their final respects. Rinfret was buried in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Georges Pelletier*, an editorial writer at Le Devoir who had known Rinfret 30 years earlier when they were both correspondents in the House of Commons, aptly summed up the man when he wrote on the day of the burial: “He was, at heart, an artist, a dilettante; circumstances had thrown him into politics, where his way with words, his wit and his social ease had carved out a successful career for him … he was an art critic, a fine mind lost in the cacophony of public conflict.”

A partial list of Fernand Rinfret’s writings appears in Renée Geoffrion, Notes bio-bibliographiques sur l’honorable Fernand Rinfret, politicien, orateur et écrivain (Montréal, 1952).

Ancestry.com, “Ontario, Canada, Roman Catholic baptisms, marriages, and burials”: www.ancestry.ca (consulted 29 Nov. 2017). BANQ-CAM, CE601-S33, 1er mars 1883. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “California death index, 1905–1939”: www.familysearch.org (consulted 29 Nov. 2017). LAC, “Diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King”: www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/prime-ministers/william-lyon-mackenzie-king/Pages/diaries-william-lyon-mackenzie-king.aspx (consulted 1 Dec. 2017). Le Canada (Montréal), 21 juill. 1939. Le Devoir, 13, 17, 18, 19, 20 juill. 1939; 13 sept., 22 déc. 1941. BCF, 1933: 23. C.-V. Marsolais et al., Histoire des maires de Montréal (Montréal, 1993). Victor Morin, “L’Honorable Fernand Rinfret (1883–1939),” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 34 (1940): 117–19. Rumilly, Hist. de Montréal, vol. 4: 167–96.

Cite This Article

Benoit Longval, “RINFRET, FERNAND (baptized Louis-Édouard-Fernand),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rinfret_fernand_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rinfret_fernand_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Benoit Longval |

| Title of Article: | RINFRET, FERNAND (baptized Louis-Édouard-Fernand) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |