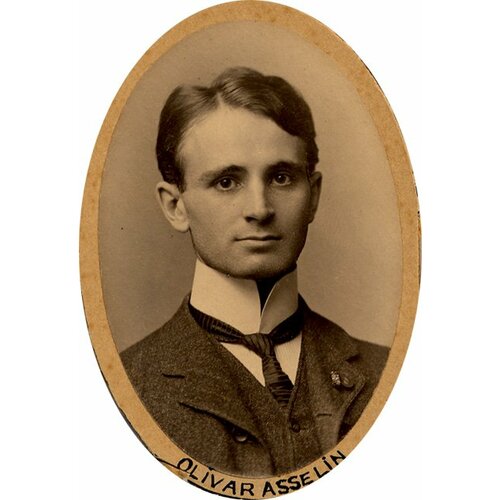

![Description English: Olivar Asselin (1874-1937) Français : Olivar Asselin (1874-1937) Date Inconnue Source [1] Author Anonyme

Original title: Description English: Olivar Asselin (1874-1937) Français : Olivar Asselin (1874-1937) Date Inconnue Source [1] Author Anonyme](/bioimages/w600.7213.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

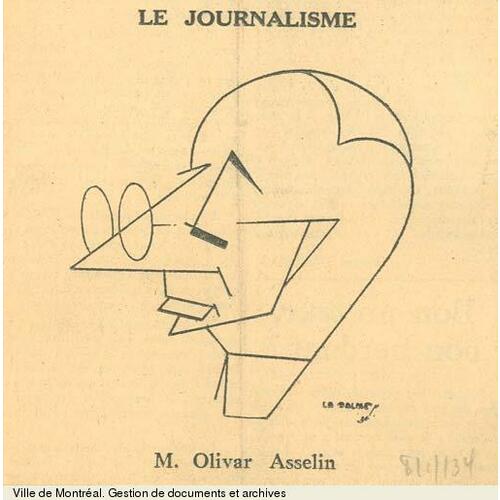

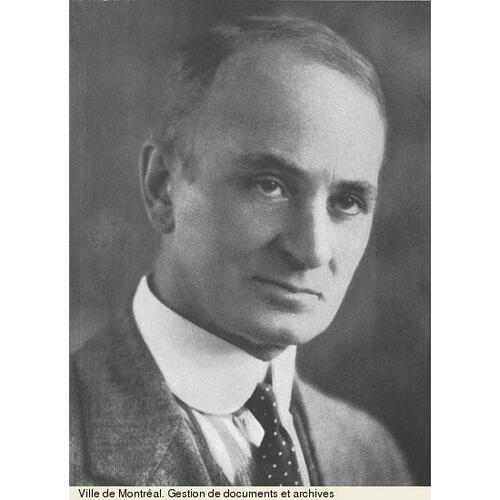

ASSELIN, OLIVAR (baptized Joseph-François-Olivar), journalist, polemicist, newspaper editor-in-chief and owner, office holder, real estate agent, soldier, and philanthropist; b. 8 Nov. 1874 in Saint-Hilarion-de-Settrington (Saint-Hilarion), Que., son of Rieule Asselin and Cédulie Tremblay; m. 3 Aug. 1902 Alice Le Boutillier (Le Bouthillier) in L’Anse-au-Griffon (Gaspé), Que., and they had four sons; d. 18 April 1937 in Montreal.

Olivar Asselin was the fourth child of Rieule Asselin, a master tanner, farmer, churchwarden, and mayor of Saint-Hilarion-de-Settrington, and his third wife, Cédulie Tremblay. The couple had a high regard for education and books. A Liberal in politics, the master tanner was personally involved, as a witness for the prosecution, in the famous 1876 trial for “undue influence” on the part of the clergy, following the defeat of the Liberal candidate Pierre-Alexis Tremblay* by the Conservative Hector-Louis Langevin* [see Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier*]. This was a time when it was risky to declare oneself a “rouge” in a remote village in Quebec where the curé, Jean-Baptiste-Ignace Langlais, controlled parish and community life. Although Olivar was only two years old when these events occurred, as a result of the family’s persistent retelling of them they would determine his subsequent battles as a polemicist against clerical interference in the public life of his day.

After four years of all kinds of harassment by Father Langlais and his Conservative allies, Rieule Asselin moved to Sainte-Flavie, on the south shore of the St Lawrence. There were six children in the family when their father set up his new tannery there. Olivar and his elder brother Raoul distinguished themselves academically at the local school. Encouraged by the curé Charles-Godefroi Fournier, the Asselins enrolled their two sons in the Séminaire de Rimouski. From the time he arrived there in 1886, Olivar attracted attention because of his precocious talent, his insatiable intellectual curiosity, and his outstanding performance in every subject, including sports. Although he was small, he already had a visible influence over his schoolmates. Given his admiration for Napoleon, he was nicknamed “the little corporal.” The coadjutor and future bishop of the diocese of Rimouski, André-Albert Blais, having newly arrived in 1889, soon took him under his wing. Year after year, his studies were crowned with success until he reached his sixth year (Rhetoric). In 1890 Olivar learned that his father’s tannery had been destroyed by fire and that he would no doubt have to abandon his schooling in order to help support his family. Shortly thereafter, like hundreds of their fellow citizens from the lower St Lawrence region, the Asselins chose exile and the cotton mills of Massachusetts.

Fall River, where the family settled in 1892, was then considered the centre of French life in New England. Despite their revulsion, Olivar and the older family members were soon at work in nearby factories. Compulsive in his reading, frustrated in his intellectual ambitions, and affected by his father’s death the following year, Olivar took some steps towards becoming a Jesuit. At this point he discovered piles of newspapers from France in the basement of the parish church. He was thunderstruck: he would be a journalist – and a pamphleteer, like the very Parisian Henri Rochefort, Marquis de Rochefort-Luçay.

In 1894, after some of his writing had attracted attention, Asselin was hired by Adélard Lafond of Le Protecteur canadien. Assigned to cover municipal affairs, he became aware of the extreme urban poverty that was rife in Fall River. He spent time with the disadvantaged and shared with them his meagre salary of $12 a week. Having worked briefly that year at Le National in Lowell and in 1895 at Le Jean-Baptiste in Pawtucket, R.I., in 1896 he moved up to be editorial secretary of the Woonsocket La Tribune. In its pages he urged French Canadian émigrés to take out American citizenship, denounced the assimilationist designs of the Irish bishops in New England, condemned Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier*’s “treason” in the settlement of the Manitoba separate schools crisis, and attacked the partisan policy shifts of Laurier’s organizer, Joseph-Israël Tarte*.

In 1898 the Spanish-American War distracted “the little corporal” from his editorials and dazzled him with prospects of military glory. Asselin abruptly enlisted in the United States army, but too late to reach the combat zone. Once the war was over, he was demobilized in August with a modest rank – as a corporal!

Asselin arrived in Montreal in 1900. Montreal journalist Robertine Barry*, who was the mentor for poet Émile Nelligan* and whom he had met in 1894, persuaded him to join the team that began to publish Les Débats in December 1899. This was a vigorous weekly in the literary and artistic avant-garde that was put by its youthful founders at the service of the new nationalist leader, Henri Bourassa*, who had just broken with Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s party in protest against Canada’s participation in the South African War. Asselin contributed poetry and commented on the literary soirées held at the Château Ramezay. He also wrote about the attack on the premises of the Université Laval in Montreal by students from McGill University, who had gone there to punish their French Canadian colleagues for refusing to take part in the war; he assailed the attitude of Archbishop Paul Bruchési, who was ready to try any and all means to restore good relations, and the bias shown by the English-language newspapers in the whole affair. He entitled his reports “Guerre de race.” The editorial position of Les Débats, however, lasted less than a year in the face of Tarte’s manoeuvring to get the paper purchased by supporters of Laurier. Meanwhile, the tanner’s son had been frequenting the École Littéraire de Montréal and had become involved with the St Vincent de Paul Society of Montreal to help homeless people in the downtown area.

In 1901, then, Asselin was unemployed. Wanting to marry and settle down, he accepted a position as secretary to Lomer Gouin*, minister of colonization and public works in the provincial Liberal cabinet of Simon-Napoléon Parent*. He married Alice Le Boutillier in L’Anse-au-Griffon on 3 Aug. 1902. The next year, totally caught up in the nationalist movement, he helped found the Ligue Nationaliste Canadienne. He organized the speaking tours that Bourassa undertook in order to explain the league’s main principles: the greatest possible autonomy for Canada with respect to Great Britain in economic, political, and military matters; the greatest possible autonomy for the Canadian provinces with respect to the federal government; and the adoption by the federal and provincial governments of an essentially Canadian policy of economic and intellectual development.

The following year, judging a newspaper indispensable for propagating the league’s ideas, Asselin gave up his job and joined with other shareholders, including Henri Bourassa and his father, Napoléon*, in founding Le Nationaliste. This Montreal weekly assembled a brilliant team of young contributors, including Éva Circé*, Jules Fournier*, Omer Héroux*, Arthur Laurendeau, and Armand La Vergne. For four years, with Asselin as editor, Le Nationaliste engaged in every federal and provincial debate. Along with his career as an editorialist, the polemicist would soon become an essayist and begin to publish his famous “Feuilles de combat” himself. From 1909 to 1933 he would write some 20 of these booklets, dealing with the most varied controversial topics, including nationalism, education reform, emigration, the French language, the bishops and World War I, intellectual life, the political legacy of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the writings of Abbé Lionel Groulx*, and the failure of the Canadian confederation.

In 1904 Asselin ran as the Nationaliste candidate for the riding of Terrebonne in the provincial general election. The seat was won by his opponent, Jean Prévost*. The journalist’s debts piled up and libel suits multiplied. He served his first jail term in 1907, and went to prison again in 1909 for slapping the face of the minister of public works and labour, Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*, on the floor of the Legislative Assembly.

In January 1910, secretly embarrassed by Asselin’s outbursts and wanting to have a daily newspaper that would be under his own control, Bourassa founded Le Devoir in Montreal. But he could not do without the support of his fiery lieutenant. After a few months of uneasy collaboration, during which Bourassa kept for himself the editorial department and the burning issue of the navy while the former editor of Le Nationaliste was relegated to the city desk, Asselin and his friend Jules Fournier walked out. By now the father of four boys, Asselin was out of work again.

To support his family, Asselin became a real estate agent. He contributed occasionally to L’Action, which Fournier founded in Montreal in 1911. That year he ran as the Nationaliste candidate for the riding of Saint-Jacques in the federal election, and was defeated. In 1912 Asselin temporarily left his job at the Crédit Métropolitain and went to Europe on behalf of the new federal Conservative government of Robert Laird Borden, which had commissioned him to do a study on immigration. In the midst of the fight against Regulation 17 in Ontario [see Sir James Pliny Whitney*], he found himself pressed into the presidency of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal in 1913 and 1914. He organized the fundraising campaign of Sou de la Pensée Française to contribute towards the survival of the newspaper Le Droit, published in Ottawa since the beginning of 1913 to champion the school rights of Franco-Ontarians, which were under attack. The campaign raised $15,000, enough to guarantee the stability of the newspaper, which was still being published in 2004.

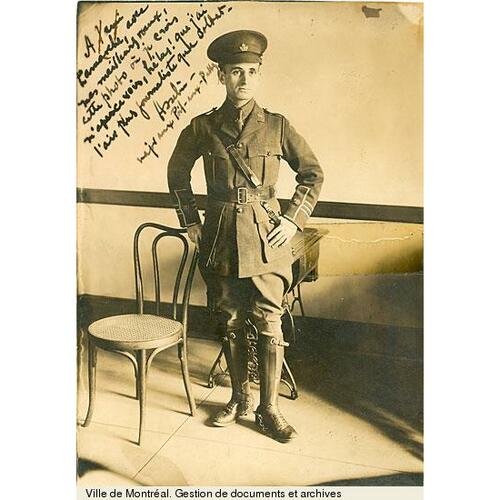

When World War I broke out, Asselin was deeply distressed by the occupation of France and the suffering there. In November 1915, after much hesitation, he decided to volunteer. The minister of militia and defence, Sir Samuel Hughes*, invited him to raise a battalion of French Canadian infantry in Montreal. Asselin, who had been out of work because of growing difficulties being experienced by the Crédit Métropolitain, and whose eldest son, Claude, had just died, hastened to accept. The members of the nationalist movement, who had protested in 1899 against Canada’s participation in the South African War, became openly opposed to enlistment in 1915 and denounced his action. Settling for the rank of major and the title of second in command, Asselin entrusted the command of his unit to a career soldier, Lieutenant-Colonel Henri DesRosiers. He himself proved a respected and admired leader of the 33 officers and the 860 men and non-commissioned officers whom he recruited over the winter.

After a few months of training in Bermuda, where the 163rd Infantry Battalion, known as the Poil-aux-Pattes, arrived in May 1916, it was sent to England on 17 November and disbanded by the British high command on 8 Jan. 1917. Asselin was stunned. His precious recruits were dispersed into other battalions. While finishing his training as an officer, Asselin immediately applied for a transfer to Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas-Louis Tremblay’s 22nd Infantry Battalion, the only French-speaking unit to fight on the front line in France [see Henri Chassé*]. His request was granted at the end of February 1917, in time for him to take part as a lieutenant in the attack on Vimy Ridge, in France. He was awarded a special citation for his acts of bravery. As a result of having lived with death and experienced the unspeakable horror of being under fire, he rediscovered his faith and began practising his religion again. An unfortunate attack of trench fever in May led to his temporary withdrawal from the front. Stormy disagreements with Tremblay about disciplinary matters made his return to the 22nd highly improbable. In the course of the last months of 1918 he finally obtained a transfer to the 87th Infantry Battalion (Canadian Grenadier Guards) and took part in the liberation of villages on the border between France and Belgium. Soon after the armistice, Asselin was offered a position as adviser to the federal minister of justice, Charles Joseph Doherty, who represented Canada at the peace conference. The Treaty of Versailles, which was signed at its conclusion, would be a great disappointment to Asselin, an ardent francophile who, as a lowly civil servant, feared above all else Germany’s rearmament.

After his demobilization in the summer of 1919, Asselin returned to Montreal, with no job prospects and debts of $15,000. The Liberal newspapers, outraged by his spirited contribution to Laurier’s defeat in 1911, closed their doors to him. He deliberately did not apply to the only independent newspaper that might have found room for a Nationaliste, Le Devoir. One small consolation: he was made a knight of the Legion of Honour by the French government. He soon found a position as a publicist with the investment brokerage firm of Versailles, Vidricaire, Boulais, Limitée. For a salary of $6,000 a year, he wrote an information bulletin sent out free of charge to all clients: La rente: guide de l’épargne et du placement. He used it to promote French Canadian economic nationalism and to denounce social injustices, American lack of culture, and deficiencies in the written language of advertising and newspapers. He would hold this position until 1925, when he moved to the brokerage of L. G. Beaubien et Compagnie Limitée.

For the gagged polemicist, his time at La rente was like a long journey across the desert. It did not prevent Asselin from indulging his taste for literature. He and Thérèse Fournier (the widow of Jules, who had died in 1918) prepared a posthumous edition of the manuscript of Anthologie des poètes canadiens and he wrote the preface. The volume came out in Montreal in 1920. In 1922, also in Montreal, they published Mon encrier . . . , a two-volume collection of Fournier’s best political and literary articles. Again it was Asselin who did the preface. He corresponded regularly with the literary critic and former priest Louis Dantin (pseudonym of Eugène Seers*), who was living in exile at Harvard University, near Boston. He contributed to L’Action française, the Montreal journal founded and edited by the historian and priest Lionel Groulx. Shaped by the ultramontane tradition of Jules-Paul Tardivel*, Groulx, through his classes, lectures, and articles, was beginning to make a name for himself among Bourassa’s disciples, who were disappointed by their leader’s disengagement from politics. Despite his decidedly Liberal roots, Asselin also soon recognized that the young priest would be the next leader of nationalist thought. Asselin wrote detailed articles for L’Action française, almost all of them based on the need for economic independence as the inescapable road to political independence.

In 1925, through a combination of circumstances, Asselin took over a charitable organization, a shelter struggling to survive ever since its establishment in 1915 by a volunteer, Achille David. He soon ensured its stability and growth. In 1926 it became the Refuge Notre-Dame-de-la-Merci, on Rue Saint-Paul in Montreal, accommodating homeless, ill, or abandoned elderly men. Asselin asked the Frères Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Dieu, in Lyons, France, to take charge of the operation.

Truly obsessed by the cause of the poor, at a time when he was going through an intense period of spiritual development, Asselin involved all his acquaintances in the fundraising activities of the shelter. Senator Joseph-Marcellin Wilson, a major financial backer of the Liberal Party and one of the charity’s benefactors, became literally infatuated with him. In 1930 he saw Asselin as the leader of men, the prestigious journalist, the only one capable of reviving the party’s organ, Le Canada, which had been without an editor since Fernand Rinfret had left four years earlier. Overlooking the insult he had suffered in 1909, Taschereau – who had become premier of Quebec in 1920 – invited his former attacker to become editor-in-chief of the Montreal newspaper. At the same time, he made an offer that the born polemicist could not resist: to fight the rise of the populist leader Camillien Houde*, who had become head of the provincial Conservative Party in 1929. Asselin agreed to take on an unlikely challenge – to reconcile the newspaper’s partisan allegiance with his own fiercely independent spirit. He would not be particularly successful.

Asselin did, however, radically change the paper’s appearance, moved the editorials to the front page, and recruited some talented young people. He was looked up to as a mentor by journalists such as Willie Chevalier, Eustache Letellier de Saint-Just, Odette Oligny, Ernest Pallascio-Morin, Robert de Roquebrune, and Edmond Turcotte. He was inflexible in the matter of correct use of language. He supported the Taschereau government in the priorities it accorded free enterprise and in the distaste it showed for state intervention, even in the area of natural resources. Here Asselin distanced himself from the positions he had taken before the war in Le Nationaliste. When the Action Libérale Nationale began to make its presence felt, he would apparently transfer to Paul Gouin* the half-hearted confidence he had previously placed in his father, the former Liberal premier Sir Lomer Gouin.

Less closely tied to the party line in culture than in politics, the Liberal paper under Asselin was, indeed, innovative in its treatment of the arts and literature. He gave ample space to columns on the cinema and the theatre. He discussed books and essays that were often regarded with suspicion by the clergy. In 1934, worn out by its long stay in power, the Taschereau government was flagging, and Asselin, no longer feeling as justified in supporting it with his pen, handed in his resignation. Now 59 years old, he again dreamed of having his own newspaper. This would be L’Ordre, a Montreal political and literary daily, which he founded enthusiastically on 10 March 1934.

Asselin proved to be in full possession of his editorial skills and his gift for recruiting young talent, including a number of his former colleagues at Le Canada. His brilliant team included such names as Jules Bazin, André Bowman, Berthelot Brunet, Gérard Dagenais*, Dollard Dansereau, Lucien Parizeau, and Albert Pelletier. Among the other noteworthy contributors who joined them were Jovette-Alice Bernier*, Alfred DesRochers*, Françoise Gaudet-Smet [Gaudet*], Jean-Charles Harvey*, Marie Le Franc, Clément Marchand*, Brother Marie-Victorin [Conrad Kirouac*], and Gérard Morisset*. In keeping with the personal evolution of its founder, L’Ordre preached a nationalism that was expressed more in the defence of the French language and the promotion of a true national education than in the field of political activism. In the midst of an economic crisis, he was suspicious of the distorted workings of the parliamentary system, but especially of state intervention, the dreaded source of centralized power in the hands of the federal government. In economic matters, he now put his trust in free enterprise to ensure a return to prosperity.

The particularly liberal positions taken by Asselin’s newspaper on culture and education were often questioned by the bishops, who were quick to let it be known. Clerical influence, along with chronic financial difficulties, caused the newspaper to cease publication on 11 May 1935. In the final issue the editor-in-chief announced the forthcoming appearance in Montreal of a new political and literary weekly, La Renaissance. Not drawn to the alternative potentially offered by the opposition of Paul Gouin with the Action Libérale Nationale, or that of Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis* with the Union Nationale, Asselin opted in the new publication for “the lesser evil” by giving vague support to the Liberal Party. Despite its high literary content and the quality of its contributors – most of whom had formerly worked at L’Ordre – La Renaissance published only 26 issues before it also succumbed in December.

On 11 June 1936, shortly before his party was defeated by the Union Nationale, Premier Taschereau resigned and handed the reins of power to his minister of agriculture, Adélard Godbout*. On the same day, Godbout hastily appointed Asselin chairman of the Quebec Old Age Pensions Commission, which had been set up the previous day by the Taschereau government. After his party’s victory on 26 August, the new premier, Duplessis, agreed to keep the former nationalist leader, now weakened and chronically in need, in this office, but on 12 Feb. 1937 Asselin, who was suffering from arteriosclerosis, was forced to resign. His application for a pension was rejected.

Olivar Asselin died at his home on Rue Saint-Hubert, Montreal, on 18 April, at the age of 62. The anticlerical polemicist was buried in the habit of the Frères Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Dieu, with whom he had recently become affiliated as a member of their third order. At his request, his military decorations were pinned to his chest. A lengthy funeral procession of paupers and former prisoners, with a sprinkling of notables, accompanied the hearse to the church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste, where Abbé Groulx, assisted by Abbé Louis-Philippe Perrier, conducted the funeral of his most paradoxical champion.

A bibliography of the works of Olivar Asselin has been published in the first two volumes of the author’s biography of him, Hélène Pelletier-Baillargeon, Olivar Asselin et son temps (2v. parus, [Montréal], 1996–?). These volumes contain an exhaustive list of all the newspapers and publications to which he contributed, as well as a list of the “Feuilles de combat” that he published on his own account. A third and final volume, which will cover the years 1919 to 1937, is in preparation.

Asselin’s personal papers are at the Ville de Montréal, Section des archives, BM55. His war correspondence (1915–19) with his family and relatives forms part of a private collection held by his grandson, A.-P. Asselin (Montreal).

The annotated bibliography found in the author’s volumes also contains a list of works that bring together some of Asselin’s texts, such as Joseph Gauvreau, Olivar Asselin, précurseur d’action française: le plus grand de nos journalistes, 1875–1937 (Montréal, 1937), in which there are three articles published on 23 and 30 April and 7 May 1937 in Le Progrès du Golfe (Rimouski, Qué.), and Olivar Asselin, Pensée française: pages choisies (Montréal, 1937), Trois textes sur la liberté (Montréal, 1970), Liberté de pensée: choix de textes politiques et littéraires (Montréal, 1997). The bibliography also lists biographies of Asselin: Hermas Bastien, Olivar Asselin (Montréal, 1938), and M.-A. Gagnon, La vie orageuse d’Olivar Asselin (2 tomes en 1v., Montréal, 1962) and Olivar Asselin toujours vivant (Montréal, 1974).

There are a number of photos of the subject in A.-P. Asselin’s private collection; a large proportion appear in M.-A. Gagnon, Olivar Asselin toujours vivant, as well as in the author’s volumes. Other photos, fewer in number, are available at the Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec (Montréal), the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal, and the Royal 22nd Regiment Museum (Quebec).

Arch. Nationales du Québec, à Québec, CE304-S8, 8 nov. 1874. Soc. de Généalogie de Québec, Fichier Drouin, L’Anse-au-Griffon (Gaspé, Qué.), 3 août 1902 (mfm). Le Devoir (Montréal), 19 avril 1937.

Cite This Article

Hélène Pelletier-Baillargeon, “ASSELIN, OLIVAR (baptized Joseph-François-Olivar),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 3, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/asselin_olivar_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/asselin_olivar_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hélène Pelletier-Baillargeon |

| Title of Article: | ASSELIN, OLIVAR (baptized Joseph-François-Olivar) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 3, 2026 |