Source: Link

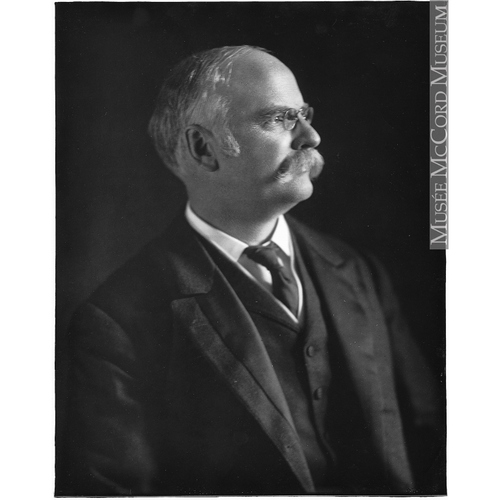

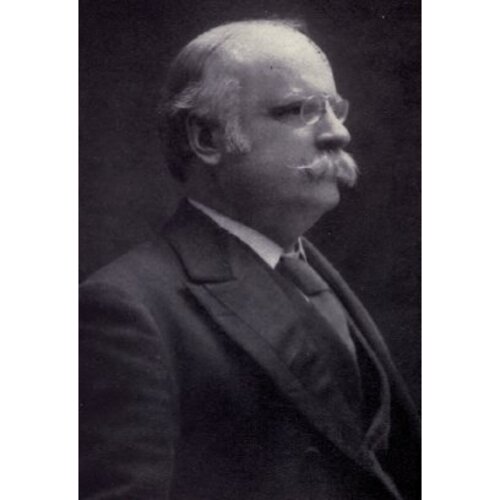

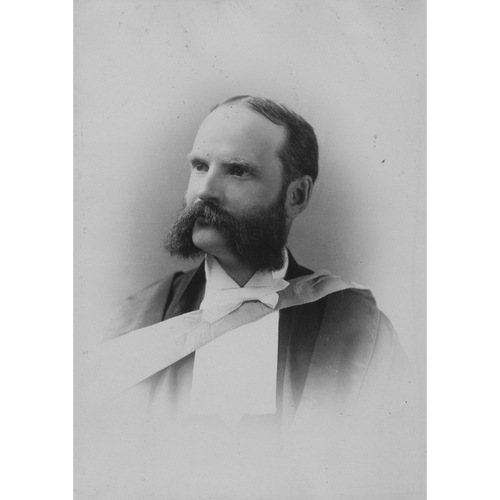

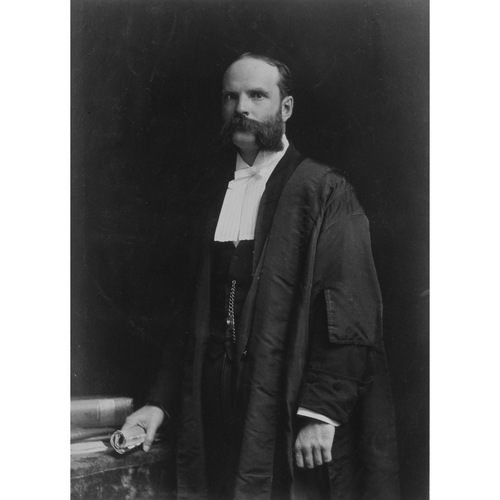

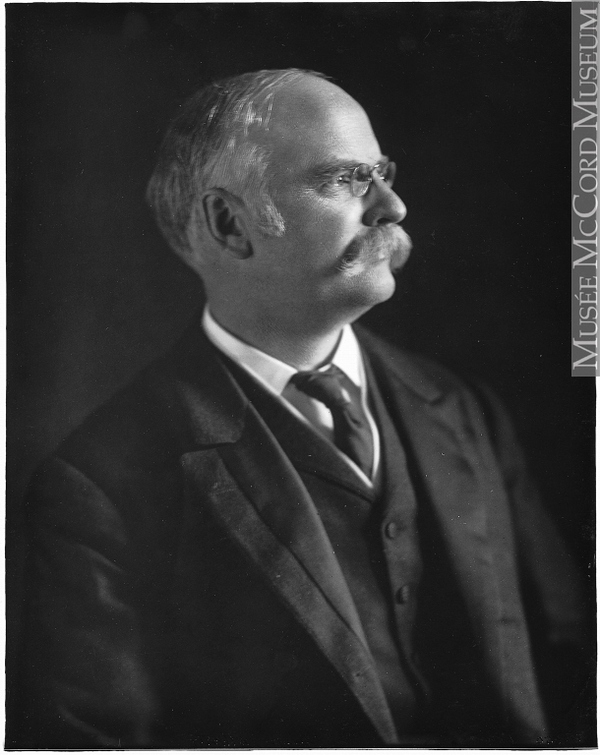

DOHERTY, CHARLES JOSEPH, militia officer, lawyer, professor, judge, and politician; b. 11 May 1855 in Montreal, son of Marcus Doherty and Elizabeth O’Halloran; m. there 6 June 1888 Catherine Lucy Barnard, and they had one son and four daughters; d. there 28 July 1931.

Charles Joseph Doherty was born into a prominent Irish Canadian family that bridged Montreal’s two solitudes, being both anglophone and, like most francophones, Roman Catholic. His father had served with distinction as a puisne judge of the Superior Court of Quebec for many years.

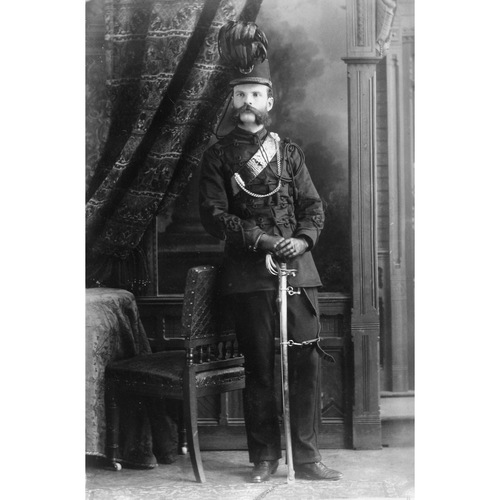

After completing his primary education with the Brothers of the Christian Schools, during which time he acquired basic fluency in French, Charles entered the Collège Sainte-Marie, where he studied in English and won several academic proficiency awards. He then enrolled at McGill College (it would become a university in 1885), graduating in 1876 with a bachelor’s degree in civil law and earning the Elizabeth Torrance Gold Medal. He was called to the Quebec bar the following year. As a young man he distinguished himself as a scholar and an athlete. He served with the 65th Battalion of Rifles (Mount Royal Rifles) during the North-West rebellion of 1885 [see Louis Riel*] and reached the rank of lieutenant.

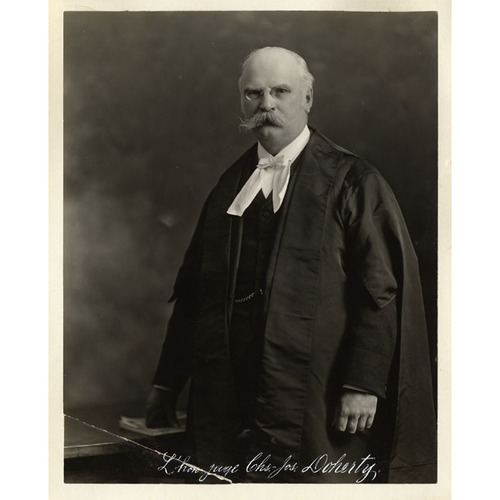

Shortly after he had been called to the bar, Doherty established a private practice in Montreal with one of his brothers, Thomas James. Charles’s growing prominence in the legal profession led to appearances before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London and part-time employment as a professor of civil and international law at McGill University from 1887 to 1907. Among his cases were several prominent libel suits as well as labour and municipal law litigations. He was appointed a judge of the Superior Court of Quebec in 1891, aged only 36, and he would hold the position for 15 years, retiring in 1906. In a tribute published in the Canadian Bar Review on the occasion of his passing, Doherty was lauded as “a judge [who] achieved a reputation for profound learning and strict impartiality.” A former schoolmate, who argued cases in courtrooms where Doherty presided, noted that even at the bar he could not help “seeing both sides of a case.” In one prominent case, Doherty had dismissed a lawsuit against Catholic Archbishop Édouard-Charles Fabre*, ruling that an old French legal precedent allowing civil authorities to intervene in disputes between the Church and its believers no longer held any validity in Canada. Long after he had retired as a justice, Doherty continued to be referred to, respectfully and affectionately, as “Judge Doherty.”

Doherty played an instrumental role in establishing the Canadian Bar Association. In September 1912 the American Bar Association held its annual meeting in Montreal. As Canada’s minister of justice and attorney general, Doherty helped host the visiting lawyers. Later that year, in Winnipeg, he suggested that a Canadian version of the bar association be formed. When his proposal was acted upon, he became the first honorary president, an office he would hold until his retirement from politics in 1921.

Before being named to the Superior Court of Quebec, Doherty had run unsuccessfully for political office, not once but twice. In 1881 he had offered himself as a Conservative candidate for the provincial riding of Montreal West and in 1886 for Montreal Centre, but to no avail; the pendulum in Quebec politics was swinging towards the Liberal Party, led by Honoré Mercier*. Upon the recommendation of the federal government, still safely Conservative under Sir John A. Macdonald*, he was made a qc in 1887. During his 15 years on the bench Doherty had to take a strict hiatus from partisan politics, reinforcing his reputation for integrity and balanced judgement. His credibility was further enhanced by McGill’s award of a dcl in 1893 and an honorary lld from the University of Ottawa in 1895. In 1903 he became a governor of the Université Laval in Quebec City. When he left the Superior Court of Quebec at age 51, he proceeded to collect a string of directorships for blue-chip companies such as the Banque Provinciale du Canada and Capital Life Assurance of Canada. In 1908, when prominent federal Conservatives asked him to stand for election in the Montreal riding of St Anne, he was ready to try politics again. This time he was victorious, no doubt assisted by the fact that a majority of his future constituents were, like him, both anglophone and Catholic.

Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberals won the election, but among the Conservative opposition members was a promising group of new parliamentarians who included Doherty and Arthur Meighen*, a future prime minister. None moved up the ranks as quickly as Doherty. Though a freshman mp, in April 1909 he was chosen to present a motion of censure alleging incompetence and dishonesty in the Department of Marine and Fisheries. During the 1910 session he criticized the Liberal government’s Naval Service Bill [see The prime minister: external relations] while expressing sympathy with the views of his fellow Quebec Conservative, Frederick Debartzch Monk*, an outspoken advocate for greater autonomy for Canada within the British empire. When some veteran Tories in the caucus sought to force out party leader Robert Laird Borden, Doherty sprang to his defence. Throughout 1910 he accompanied Borden on campaign-style speaking tours of the country. He still found time to take part in Catholic celebrations at the 21st International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal and to offer public support for Irish Home Rule within the British empire. While a stereotypical Tory leader might have recoiled, Borden did not, and he made Doherty his seat-mate in parliament. When the Conservative filibuster against the government’s reciprocity legislation precipitated an early election in 1911, Doherty worked to ensure cooperation within Quebec between traditional Conservatives, members of the Nationaliste movement [see Olivar Asselin; Henri Bourassa*] such as Monk, and ex-Liberals.

Laurier’s government was defeated at the polls in September 1911, and the new Conservative caucus counted over two dozen mps from Quebec, including Doherty. When Borden chose his cabinet in October, Judge Doherty, as he was still often called, became the new minister of justice and attorney general. Had Borden followed the tradition established by Macdonald, he would have elevated a French Canadian mp to that post. The prime minister opted instead for the Irish Catholic Quebecer whose judicial experience, proven loyalty, and moderately autonomist views of Canada’s place within the British empire promised to wear well in the aftermath of the divisive 1911 election. During his early years in office Doherty gained a reputation as a competent, not overly partisan minister whose inclination was to forgo federal intervention in provincial affairs in favour of provincial autonomy. In September 1912, when Borden announced the controversial Naval Aid Bill, under which Canada would contribute the huge sum of $35 million to the government of the United Kingdom in support of the imperial navy, Monk resigned from his post as minister of public works, and several Nationaliste backbenchers sided with the opposition. Doherty supported the bill but was less involved in steering it through the House of Commons than his colleague Arthur Meighen. Behind cabinet doors, Doherty did not hesitate to speak his mind, locking horns on one occasion with the postmaster general Louis-Philippe Pelletier*, and on another with Samuel Hughes*, the mercurial minister of militia and defence, regarding arrangements for a military parade in Montreal. He kept his leader’s confidence, however, and served as acting prime minister in July 1914 while Borden vacationed.

When the First World War broke out in Europe, Canada was a British colony and thus constitutionally obligated to take part when the United Kingdom entered the conflict. As a self-governing dominion, however, the degree of Canadian involvement was for its own parliament to decide. In August 1914 virtual unanimity existed between the two major parties as to Canada’s attitude; Laurier captured the mood in the House of Commons on the 19th when he declared that the only possible response was “the British answer to the call of duty: ‘Ready, aye ready.’” Under Doherty’s direction, and assisted by Borden, Meighen, and experts from the Department of Justice (such as William Francis O’Connor), a bill was drafted to grant the federal cabinet vast emergency powers to oversee the young nation’s efforts in what was expected to be a short conflict. Though the War Measures Act potentially enabled the government to ignore many traditional liberties, it was nevertheless carried unanimously after little debate. The act provided the legal basis for the internment of hundreds of Germans and thousands of Ukrainian and Polish workers who were still Habsburg subjects [see William Perchaluk*], a task that Doherty delegated to Sir William Dillon Otter*. The minister would defend this policy in the House of Commons on 22 April 1918 by arguing that the articles in the Hague Convention on prisoners of war did not apply to civilians.

As the expected early military victory did not materialize, the strains of total war began to wear on national unity. The forces of disunity were augmented by the controversy surrounding a 1912 Ontario educational directive known as Regulation 17 [see Sir James Pliny Whitney*]. It stipulated that beyond the first two years, the language of instruction in all publicly funded schools would henceforth be English. Franco-Ontarians, accustomed to bilingual schools, were outraged, as were francophone Quebecers [see Samuel McCallum Genest]. Borden’s cabinet was pressured to repeal the provincial policy. Doherty, like Borden, strongly opposed federal intervention because it was likely to stir up animosity in English-speaking Canada, and their view prevailed. Doherty was personally in favour of bilingualism, however, and sympathized with the motives of the petitioners. In the House of Commons on 11 May 1916 he declared: “In my own province I am one of the minority from the point of view of language. Throughout this Dominion, I am one of the minority from the point of view of religion.”

The year 1917 was decisive for Canada. The war that was supposed to have ended quickly had dragged on for three bloody, destructive years. With casualties outpacing new recruits, Prime Minister Borden concluded that a military draft would be necessary to meet his prior commitment of half a million Canadian soldiers. Conscription of men for overseas military service was a divisive subject. Laurier and members of his Quebec caucus adamantly opposed the policy, but many English-speaking Liberals were equally staunch in supporting it. Doherty was approached by Cardinal Louis-Nazaire Bégin* to urge a moderate course, but on this issue he stood with his leader and against any attempts by clerical authorities to dictate to ministers of the crown. It was Doherty who piloted through parliament the Military Voters Bill, which was designed to facilitate voting by all those in the Canadian military service, including female nurses and soldiers under 21 [see The right to vote in federal elections]. During the subsequent election campaign, Doherty made his views clear. In a speech delivered in Montreal on 29 October, he declared, “When the Homeland is attacked, the whole Empire is attacked, and within that Empire Canada is attacked.” By this time pro-conscription Liberals had joined forces with Borden’s Conservatives to form the Union government. Doherty continued to serve as the minister of justice, and he figured prominently in the Unionists’ election team for his home city of Montreal. Anti-conscriptionists sought desperately to disrupt the government’s election meetings in Quebec. Three times – in Montreal’s Griffintown district, Sherbrooke, and Verdun (Montreal) – Doherty parried hecklers’ jibes at the front of the hall while anti- and pro-conscription mobs engaged in pitched battles at the back and out into the streets. Doherty won his riding by a margin of almost 4,000 votes, but only two Unionist colleagues from Quebec, Charles Colquhoun Ballantyne and Sir Herbert Brown Ames*, joined him in victory. Exactly 2,000 of the 8,346 votes that Doherty received were from members of the military, all but 282 of which were cast outside North America. These numbers illustrate the electoral impact of the Military Voters Bill that Doherty had piloted through parliament. In all provinces other than Quebec the government had triumphed, however, and though Doherty retained his cabinet post, he was conscious of the fact that a large majority in Quebec had voted for Laurier and the Liberals. The election results starkly revealed how deeply the country was divided.

As minister of justice, Doherty oversaw the legal enforcement of conscription. Opposition to the Military Service Act in Quebec soon boiled over into the violent Easter riots of 1918 [see Georges Demeule*]. A large delegation of agricultural leaders from across Canada descended upon Ottawa in May, seeking to exempt farmers’ sons from the act. Through the turmoil, the government stood its ground. An incident the following month called into question the justice minister’s impartiality. Acting on rumours that there were young men evading military service at the Jesuits’ St Stanislaus noviciate in Guelph, militiamen entered the institution on 7 June and arrested several students, including Doherty’s son, Marcus Cahir, in what would become known as the Guelph raid. Even worse, the charges were dropped after the senior Doherty personally intervened, issuing instructions by telephone from Ottawa. The government attempted to prevent the story from reaching the public, which only amplified the scandal. The truth, as revealed by a judicial inquiry held a year later, was rather different from appearances. Doherty’s son had attempted to join the military but was declared medically unfit. Moreover, since he had been accepted into the Jesuit order, he was exempt from conscription, but during the raid he did not have his certificate to prove it. His father had simply acted to prevent a miscarriage of justice. The attempt to suppress the story was deemed prudent at a time of near hysteria across Canada. The report by judges William Edward Middleton* and Joseph Andrew Chisholm* completely exonerated the minister.

Before conscription, Doherty had encouraged Irish Catholics in Montreal to join the war effort and was made honorary colonel of the Irish-Canadian Rangers, deployed in 1916 as the 199th Infantry Battalion. He saw no contradiction between fighting for the British empire and supporting Irish Home Rule. In the early 1880s he had played a central role in the formation of the Montreal branch of the Irish National League, which, according to its declaration of principles, aimed “to obtain for Ireland the freedom that Canada enjoys.” He had also been president of the city’s chapter of the Irish National Land League and was one of the delegates to its convention in Philadelphia in 1883. For Doherty, justice in Ireland was inseparable from self-government. In 1917 he joined a group of leading Irish Catholics, including Charles Murphy, Francis Alexander Anglin, and Sir Charles Fitzpatrick*, in urging Borden to pressure the United Kingdom into enacting home rule immediately. In a letter supporting the group’s objectives, Doherty argued that if the war was fought for the rights of small nations, then Ireland, “the small nation that is at the household of the empire,” should be given home rule and take its place as an equal member of the British empire.

In the fall of 1918 Doherty accompanied Borden to Britain for a meeting of the imperial war cabinet, which was followed by the Paris Peace Conference. Borden, supported by Doherty, insisted that Canada be granted a separate seat at the table despite its membership in the British empire. Doherty’s views on two key issues were expressed in an internal memorandum to Borden dated 22 Feb. 1919. First, Doherty favoured the popular election of representatives to the proposed League of Nations: “The people, not the Governments alone, should have means of participating in the work of the League.” Borden did not support this idealistic notion, but he did agree wholeheartedly with Doherty on the second topic: both felt that Article X, the treaty clause that would impose obligations of collective security and, if necessary, military intervention on all signatory countries, was dangerously misguided. As Doherty pointed out in the memorandum, this clause could involve Canadians “in all the horrors of wars in which they have no interest, in order to ensure respect for decisions in which they had no part and for which they have no responsibility.” The Canadian delegation lobbied vigorously for the deletion of Article X but to no avail. When the final version of the Treaty of Versailles was presented in June, Doherty, along with Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton*, signed it on behalf of Canada.

Doherty continued to push the principle of national autonomy. When a former American president, William Howard Taft, suggested that the self-governing British dominions were not entitled to separate representation at the League of Nations, Doherty rejected this position. “We have grown up to nationhood,” he declared in the House of Commons on 11 Sept. 1919. Though Doherty had fought for the removal of Article X while in Europe, he publicly defended it against pointed criticism from the opposition Liberals when the peace treaty was presented to parliament for approval because he feared that requesting changes to the agreement would jeopardize its adoption in other countries. Later, when asked how the international labour conventions associated with the final peace settlement would be dealt with, Doherty announced that the dominion government would not attempt to use its powers to implement the package of pro-labour measures, which included provisions for a 40-hour work week and 9-hour workday. Rather, the initiative in these matters would rest with the provinces.

Upon his return from Europe in early July 1919, Doherty assumed responsibility for the national government’s role in the prosecution of labour leaders who had been arrested in June, during the final days of the Winnipeg General Strike [see Mike Sokolowiski*]. For six weeks most of the prairie city’s businesses and industries had been closed as thousands of workers collectively pressed their demands for union recognition, improved wages, and better working conditions. In Doherty’s absence Arthur Meighen, the minister of the interior and Manitoba’s representative in the Union cabinet, had served as acting minister of justice. It was he, supported by the full cabinet, who had authorized the arrest of the major strike leaders, including John Queen*, William Ivens*, and Robert Boyd Russell*, to bring the strike to an end. But it was Doherty who subsequently authorized several leading Winnipeg lawyers, all of whom had been prominent in the anti-strike Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, to prosecute the charges against the arrested labour leaders in court. Though the administration of justice is normally a provincial responsibility, the Manitoba government had declined to act through the criminal courts. By using the extraordinary powers conferred upon the dominion government by the War Measures Act, which was still in effect, Doherty circumvented the constitutional norms and enabled the prosecutions to proceed. Only three of the ten defendants were not convicted – the charges against James Shaver Woodsworth* were dropped, and both Frederick John Dixon and Abraham Albert Heaps* were acquitted. In Doherty’s mind it was a clear case of upholding the rule of law, although some historians have depicted the federal response as a heavy-handed and unjust suppression of the Winnipeg workers’ rights.

Doherty and many of his colleagues were beginning to feel the fatigue of their long years of ministerial service. Prime Minister Borden was the first to act, declaring his intention to retire in the summer of 1920. Doherty would have preferred that the former finance minister, Sir William Thomas White*, succeed Borden, but when White declined to stand, the minister of justice reluctantly accepted the choice of Arthur Meighen. Doherty knew that his native province would have great difficulty in forgiving the man associated with two hated wartime measures: conscription and the Union government.

Doherty was selected, along with Sir George Eulas Foster and Newton Wesley Rowell*, as a Canadian delegate to the first assembly of the League of Nations, which met in Geneva in November and December 1920. In his final year of politics Doherty threw himself into two causes. First, while his efforts to secure the deletion of Article X from the league’s charter had come to nothing, he was able to contribute to the formation of the Permanent Court of International Justice by serving on a panel of five international jurists named by the league to review proposals for such a body. Doherty’s views on its importance were revealed in the parliamentary speech he gave on 28 April 1921 to urge ratification of the court: “Possibly there is something more precious even than peace, namely, justice.” Secondly, Doherty introduced another bill that represented his deepest beliefs. The Canadian Nationals Act clarified the difference between a Canadian national and a British subject. Although couched in moderate language, the act represented another step forward for Canadian autonomy within the empire. Doherty’s final act of public service was to accept, along with Sir George Halsey Perley, the role of delegate to the autumn 1921 meeting of the League of Nations in Geneva. Before leaving for Europe, he submitted his resignation from cabinet to Prime Minister Meighen. While he was fighting quixotically at the Geneva meeting for the repeal of Article X, his former Conservative and Unionist colleagues were seeking re-election in Canada. Neither he nor they were successful.

Although Doherty lived for another decade, his political career was over. For a few years he played minor roles in the life of his native Montreal: serving as patron of League of Nations societies, gracing the head table at public banquets, and judging a debate between teams from the University of Oxford and McGill. He was active in a number of private clubs (Mount Royal, St James, University, and Montreal) and had returned to practising law. Owing to his reputation for integrity, the Liberal government in Ottawa retained him in 1922 as counsel in a dispute over the boundary between Labrador and Quebec. Though Doherty had fought hard for his party’s cause in three federal general elections and could be a formidable adversary in parliamentary debate, he retained to a surprising degree a judicial aura in the political arena. In a tribute published in the Canadian Bar Review after his death, lawyer and mp John Thomas Hackett described Doherty’s powers of persuasion this way: “His was a great personality, not dominant and never domineering, but always serene, always sincere; he was quietly persuasive, creating among those with whom he came into contact the impression that his was the better way and that he was reluctant to talk about it.” A proud Irish Canadian and Roman Catholic from Montreal who personified biculturalism within his country and fought for its autonomy within the British empire, for ten years Doherty provided competent leadership to the Department of Justice. Having experienced the destructive impact of modern warfare, not only on soldiers but also on nations, he placed his own hopes for humankind in the eventual triumph of justice and democracy as the best guarantors of peace.

Archival sources pertaining to this biography are limited, and all are located at LAC. A modest collection of the papers of Charles Joseph Doherty has been opened to researchers (LAC, R4647-0-9, vols.1–8). Other relevant collections at the same institution are the fonds for Sir Robert Borden (R6113-0-X), Arthur Meighen (R14423-0-6), and Henri Bourassa (R8069-0-5). The Canadian annual rev. is an invaluable source for students of this era, and was used for the years 1903–23. Doherty’s parliamentary utterances, 1909–21, can be found in Can., House of Commons, Debates. Back copies of the Montreal Gazette provide a journalistic perspective agreeable to this newspaper’s targeted readers: members of the anglophone business class of greater Montreal and its hinterland. Henri Bourassa’s newspaper, Le Devoir, is a solid source for French Canadian elite responses to significant political events in which Doherty took part.

Doherty did not leave any published memoirs, but his political boss, Prime Minister Robert Borden, did. These were originally edited by his nephew, Henry Borden, and are available in abridged form as R. L. Borden, Robert Laird Borden: his memoirs, ed. and intro. Heath Macquarrie (2v., Toronto, 1969). Other valuable biographies are: R. C. Brown, Robert Laird Borden: a biography (2v., Toronto, 1975–80); Roger Graham, Arthur Meighen: a biography (3v., Toronto, 1960–65), 1, 2; Margaret Prang, N. W. Rowell, Ontario nationalist (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1975); and R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biography (3v., Toronto, 1958–76), 1. For Doherty’s role in imperial and international diplomacy, see the following: J. G. Eayrs, In defence of Canada (5v., Toronto and Buffalo, 1964–83), 1 (From the Great War to the Great Depression, 1964); G. P. de T. Glazebrook, A history of Canadian external relations (Toronto, 1950); John Hilliker et al., Canada’s Department of External Affairs (3v., Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1990–2017), 1; and C. P. Stacey, Canada and the age of conflict: a history of Canadian external policies (2v., Toronto, 1977–81), 1. His part in federal–provincial diplomacy, particularly with regard to the dominion power of disallowance, is covered in Christopher Armstrong, The politics of federalism: Ontario’s relations with the federal government, 1867–1942 (Toronto, 1981). A valuable analysis of changes in Doherty’s political party is provided in John English, The decline of politics: the Conservatives and the party system, 1901–20 (Toronto, 1977). Doherty’s behind-the-scenes role in supporting the prosecution of the eight arrested leaders of the Winnipeg General Strike is uncovered in Reinhold Kramer and Tom Mitchell, When the state trembled: how A. J. Andrews and the Citizens’ Committee broke the Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto and Buffalo, 2010). His role in the Guelph conscription incident of 1918 is ably covered in Mark Reynolds, “The Guelph raid,” Beaver (Winnipeg), 82 (2002), no.1: 25–30. Doherty’s strong identification with Irish nationalism within the British empire is revealed in the following sources: Simon Jolivet, Le vert et le bleu: identité québécoise et identité irlandaise au tournant du XXe siècle ([Montréal], 2011); M. G. McGowan, The imperial Irish: Canada’s Irish Catholics fight the Great War, 1914–1918 (Montreal and Kingston, 2017); and Rosalyn Trigger, “Clerical containment of diasporic Irish nationalism: a Canadian example from the Parnell era,” in Irish nationalism in Canada, ed. D. A. Wilson (Montreal and Kingston, 2009), 83–96. Finally, two commemorative articles in successive issues of the Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), published at the time of his death, shed valuable light on his personal habits, personality, values, and character. The first article is based on a speech by mp J. T. Hackett, “The late C. J. Doherty, p.c., k.c., d.c.l.,” 9 (1931): 538–39; and the second is by P.-B. Mignault, “The Right Honorable Charles J. Doherty,” 9 (1931): 629–33.

Cite This Article

Larry A. Glassford, “DOHERTY, CHARLES JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 16, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/doherty_charles_joseph_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/doherty_charles_joseph_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Larry A. Glassford |

| Title of Article: | DOHERTY, CHARLES JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2023 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 16, 2025 |