Source: Link

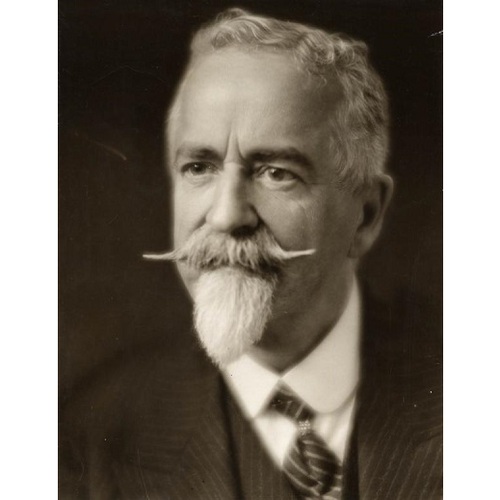

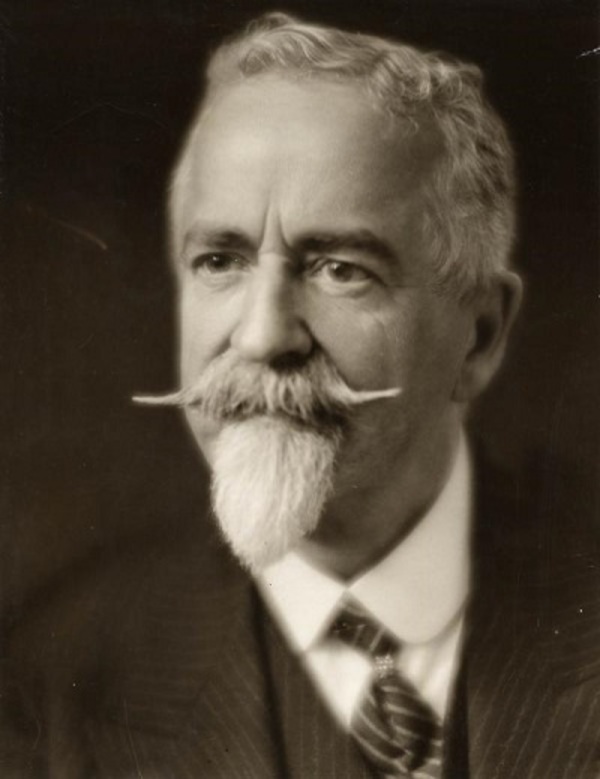

GENEST, SAMUEL McCALLUM (baptized Marie-Joseph-Samuel), civil servant; b. 10 June 1865 in Trois-Rivières, Lower Canada, son of Laurent-Ubalde-Archibald Genest, a clerk, and Emma McCallum; m. first 31 Oct. 1883 Charlotte-Annie (Anna) McConnell (d. 29 Sept. 1894) in Ottawa, and they had a son and a daughter, neither of whom survived their father; m. secondly 27 April 1896 Emma Woods in Aylmer (Gatineau), Que., and they had two sons; d. 25 April 1937 in Ottawa and was buried two days later in Aylmer.

Born of a French Canadian father and a mother of Scottish origin, Samuel McCallum Genest spent his youth in his birthplace, where he studied with the Brothers of the Christian Schools and at the Séminaire de Saint-Joseph des Trois-Rivières. His father, a prominent figure in the local elite, was a clerk by profession in the Trois-Rivières district for some 50 years. At least five members of Genest’s family were to occupy various posts in the world of provincial politics: he was the nephew of Conservative Charles-Borromée Genest, brother-in-law of the Conservative Nérée Le Noblet Duplessis and of Liberals Richard-Stanislas Cooke and William-Pierre Grant, and the uncle of Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*, leader of the Union Nationale and premier of the province of Quebec.

After being trained, Genest worked as a surveyor on the construction of the Pontiac Pacific Junction Railway, a job that led him to discover the Ottawa region. In the early 1880s he joined the federal Department of the Interior in the city of Ottawa. He was employed as a civil servant there until 1930, and held the positions of civil engineer, draughtsman, and chief draughtsman in the division of mineral statistics and mines, and director of the technical division of the dominion lands administration. His work included mapping mining sites on the prairies. He lived in Aylmer from at least 1883, and then settled in Ottawa in 1896, where he resided for the rest of his life.

As a trustee (1909–32) and chairman (1913–31) of the Ottawa Separate School Board (OSSB), which represented Roman Catholic francophones and anglophones in the city, Genest was very much involved in the fight against Regulation 17 in Ontario. This policy, adopted in 1912 by the provincial Conservative government of Sir James Pliny Whitney*, restricted the use of French as a language of instruction and communication in bilingual schools to the first two years of elementary education and stipulated that teachers must have sufficient command of English to deliver the curriculum in that language or they would be dismissed. Only those institutions that complied received the necessary government funding to operate. Genest employed a confrontational strategy during the early years of Franco-Ontarian resistance to Regulation 17, which would have consequences not only for the school board, but also for himself.

Backed by most of the francophone and anglophone OSSB trustees, Genest flatly refused to enforce Regulation 17. The board, consequently deprived of government funding for all its schools as of 1913, had to make do with money raised from school taxes. To prompt Genest to comply with the regulation, anglophone trustee Robert Mackell, five of his anglophone OSSB colleagues, and two anglophone candidates defeated in the previous school-board election turned to the courts. In April 1914 they obtained a temporary injunction, known as the Mackell injunction, which prevented Genest from borrowing funds to make up for loss of revenue and from hiring and paying the teachers who did not obey Regulation 17. Genest and most of the OSSB trustees decided to contest the injunction, and even went so far as to suspend payment of salaries to all teachers. In June the judge of the Supreme Court of Ontario’s High Court division, Haughton Lennox, ordered Genest to pay the anglophone teachers, to which he resigned himself at the end of the month. Genest was soon short of money, and on 30 June he dismissed the lay teachers, who were mostly anglophone, but committed to rehiring them if they agreed to an annual salary that would vary between $300 and $400; previously their pay could rise to $1,800. The trustees who had initiated the injunction fought this action. In September the anglophone teachers hired during the summer on the new salary scale refused to take up their posts because they had received threats from teachers who had been let go, which forced Genest to defer the start of the new school year. On 11 September a court order obtained at the request of the dissenting anglophone trustees called upon Genest to open the schools in five days and take back the dismissed teachers. Following a majority vote by the trustees, however, the chairman did not pay them, on the pretext that they were not qualified because they had been hired by the OSSB, which was not willing to obey Regulation 17. William Lee, principal of St Joseph’s School, brought proceedings against the OSSB to recover his money. On 18 November the court forced the board to repay the sums owing to the plaintiff and to those teachers who had a teaching certificate, and to do so according to the former salary scale. Ten days later Lennox declared Regulation 17 valid (the judgement was reaffirmed by the Court of Appeal in July 1915). Despite the numerous objections put forward by Genest and the board, the Mackell injunction became permanent on 28 November and would be upheld until November 1931.

In May 1915 the OSSB teachers found themselves once more without salaries. Most of them had not been paid since December. The situation incurred the wrath of the anglophone teachers, who threatened to go on strike. The Ontario Department of Education paid them directly on 1 June. The bilingual teachers, for their part, remained without salaries.

Genest had to face another obstacle. In accordance with a bill adopted in April by the Ontario legislature, the Conservative provincial government of William Howard Hearst* set up a commission in July comprising three non-elected members (Denis Murphy, Thomas D’Arcy McGee, and Arthur Charbonneau) to run the OSSB separate schools. Genest and the board trustees no longer had any powers. However, because the commission had not been elected by Catholic taxpayers, they did not recognize it and interfered in its affairs. They wanted to keep the commissioners from getting their hands on OSSB bank funds and also asked the court to prevent the Quebec Bank and the City of Ottawa from paying the commissioners the revenue collected through school taxes. In November the chief justice of the Ontario Court of Appeal, Sir William Ralph Meredith*, dismissed the petition.

The government commission refused to pay the bilingual-school teachers because they did not enforce Regulation 17. On 1 Feb. 1916 Genest, with a number of French Canadian compatriots, demanded from Ottawa’s city council the OSSB’s share of revenues from school taxes for 1915 ($85,000), but their effort was in vain. Consequently, two days later the bilingual teachers went on strike, causing the schools to close; they would not reopen until September. At the end of February Genest accompanied a delegation that, through a petition, asked the Conservative prime minister, Sir Robert Laird Borden, to disallow the law that had created the special commission. Borden addressed the situation but maintained that the federal government did not have the power to intervene since education fell under provincial jurisdiction. In November 1916 the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London declared the special commission to be unconstitutional, but not Regulation 17. The OSSB therefore took over the running of separate schools once more.

On 7 December Genest circumvented the Mackell injunction by paying the teachers of the bilingual schools, who had been without salaries for more than two years. In May 1917 John J. O’Meara, the lawyer representing Mackell and his allies, brought proceedings against Genest for contempt of court and demanded his imprisonment. The lawyer Napoléon-Antoine Belcourt, who up to that point had played a major role in resisting Regulation 17, defended him. After refusing to cooperate with the court during his cross-examination in May, Genest reversed his stand and agreed to answer questions accurately and supply the documents requested during a second cross-examination in October.

In April 1917 two laws pertaining to the OSSB received royal assent in Ontario. The first allowed the creation of another government commission if the OSSB did not comply with Regulation 17. To ensure its constitutionality, the government of Ontario turned to the Court of Appeal in October. Two months later Justice Meredith and his colleagues rendered a favourable verdict. The second law forced the OSSB to pay the expenses of the previous commission. According to Genest and his OSSB colleagues, these laws ran counter to the judgement delivered by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London in November 1916. They therefore submitted a petition to the governor general, the Duke of Devonshire [Cavendish], asking him to disallow the legislation.

To recover the money spent by the government commission, the OSSB brought a lawsuit against the Quebec Bank, the Bank of Ottawa, and the three trustees appointed by the Ontario government. In January 1918 the judge of the Ontario Supreme Court’s High Court, Roger Conger Clute, allowed the OSSB to recover the amounts, with the exception of those used for the teachers’ salaries and the running of the schools. However, the decision was overturned in October by the Court of Appeal and, a year later, by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

At the beginning of the 1920s Genest began a negotiation process with the United Farmers coalition government, which had been in power since 1919. Accompanied by representatives of the Association Canadienne-Française d’Éducation d’Ontario (of which he was president from 1919 to 1921), he met several times with the premier, Ernest Charles Drury*, and his minister of education, Robert Henry Grant*, to reach a solution to the school problem but was unsuccessful. When the Conservative government of George Howard Ferguson* (which had come to power in 1923) changed Regulation 17 in 1927 to align with the demands of the Franco-Ontarian population, Genest, satisfied with the decision, undertook to cooperate with the Department of Education and its inspectors. In so doing, he wished to facilitate the implementation of the recommendations of the Scott–Merchant–Côté report [see Francis Walter Merchant], which suggested, among other things, re-establishing the study and use of French within the framework of a bilingual education system, dividing the institutions into two categories: public schools and Roman Catholic separate schools.

From the start of the fight against Regulation 17, Genest and his Franco-Ontarian compatriots had been able to count on the support of certain members of the French Canadian elite in the province of Quebec: the author and polemicist Olivar Asselin, politician Armand La Vergne, Abbé Lionel Groulx*, journalist Omer Héroux*, and Le Devoir editor Henri Bourassa*, for example. From the 1920s onwards, some members of Ontario’s Anglo-Ontarian elite, shaken by the national crisis provoked by conscription in 1917, decided to come to the defence of the rights of French Canadians. Charles Bruce Sissons*, a professor at Victoria University in Toronto, James Laughlin Hughes, the chief inspector of Toronto schools, author Percival Fellman Morley, and lawyers William Henry Moore and John Milton Godfrey* were among them.

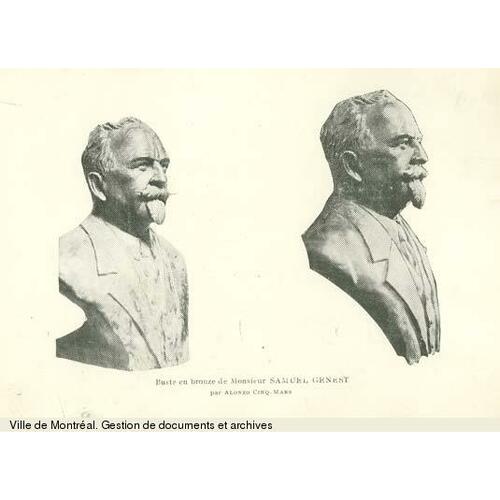

In January 1931 Genest failed to be re-elected president of the OSSB, suffering the same fate as both Aurélien Bélanger, who was forced to resign as director of bilingual schools after a motion put forward by the OSSB proposed the abolition of his post, and Belcourt, who was replaced as the lawyer for the OSSB in March. The majority of trustees wished to remove the leaders of the resistance against Regulation 17 to maintain a climate of peace. In spite of everything, Genest decided to remain a trustee, but because of health problems, he announced in November 1932 that he would not seek another term. In his honour a grand celebration took place on 27–28 Feb. 1933 at the Université d’Ottawa and the Château Laurier. Genest was presented with a bronze bust in his likeness and received several testimonials of admiration and affection. His supporters acknowledged him as one of the leaders of the resistance; according to Le Droit of 10 and 18 February and 1 March, they described him as a “champion of French survival in Ontario” and a “champion of bilingual schools in Ontario,” while his pupils “considered [him to be] … like a father who had jealously looked after the safeguarding of the French language.”

A prominent figure of the French Canadian elite in Ottawa, Genest involved himself in various French-language organizations. He was president of the Institut Canadien-Français d’Ottawa from 1905 to 1906 and the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste d’Ottawa in 1915. In 1920 he was elected an honorary lifetime officer and, in 1927, lifetime director of the Union Saint-Joseph du Canada. As well, the Association Canadienne-Française d’Éducation d’Ontario had tried unsuccessfully, in 1922, 1924, 1925, and 1926, to have him named senator. With the aim of highlighting his contribution to the struggle against Regulation 17, France conferred on him the title of Officier de l’Instruction Publique in 1927 and the College of Ottawa awarded him an honorary lld in 1928.

Genest died at his Ottawa residence on 25 April 1937 at the age of 71, a victim of hyperglycaemia caused by diabetes. His funeral was held two days later at the church of Sacré-Cœur; Guillaume Forbes, archbishop of Ottawa, gave the absolution and Joseph-Alfred Myrand, curé of the parish of Sainte-Anne, was the cantor for the service. Many citizens, representatives from the Catholic Church, the state, and the world of teaching, as well as hundreds of pupils, paid their last respects.

“An energetic figure, hot-tempered, a chivalrous character”: such were the three principal qualities attributed by Le Droit to Samuel McCallum Genest in its issue of 26 April 1937. Like other leaders of the resistance against Regulation 17 – among them Belcourt, Bélanger, Senator Philippe Landry*, and Oblate father Charles Charlebois – Genest never gave in to an assimilationist policy that lasted 15 years. He holds a place among those who devoted their lives to ensuring the survival of French in Ontario.

Some of the plans Samuel McCallum Genest prepared while working at the federal Dept. of the Interior are held at LAC, R190-36-2; R12567-126-7; R12567-129-2; R12567-130-9; R12567-132-2; R12567-134-6.

AO, RG 80-5-0-42, no.2249; RG 80-8-0-1729, no.11192. Arch. Deschâtelets, Oblats de Marie-Immaculée (Richelieu, Québec), HP 351–375. BANQ-MCQ, CE401-S48, 10 juin 1865. BANQ-O, ZQ2, 9, 1er oct. 1894, 27 avril 1896. Centre de Recherche en Civilisation Canadienne-Française (Ottawa), C2. FD, Saint-Paul (Aylmer, Québec), 27 avril 1937. Le Devoir, 26, 27 avril 1937; 3 mars 1945. Le Droit (Ottawa), 1914–37. Ottawa Evening Citizen, 4 May 1914; 12, 28, 29, 31 May, 1, 22 June 1915; 24 Oct. 1918; 26 April 1937. Ottawa Evening Journal, 26 April 1937. Saturday Evening Citizen (Ottawa), 8 Oct. 1927. Réal Bélanger, Henri Bourassa: le fascinant destin d’un homme libre (1868–1914) ([Québec], 2013). Michel Bock, A nation beyond borders: Lionel Groulx on French Canadian minorities, trans. Ferdinanda Von Gennip (Ottawa, 2014). Decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council relating to the British North America Act, 1867 and the Canadian Constitution, 1867–1954, comp. R. A. Olmsted (3v., Ottawa, 1954), 2: 123–30. Directory, Ottawa, 1880–1930. Mackell v. Ottawa Separate School Trustees (1914), Ontario Law Reports (Toronto), 32: 245–70. The Ottawa school question (Ottawa, 1914). The Ottawa separate school case (Ottawa, 1915). Ottawa Separate School Trustees v. City of Ottawa, Ottawa Separate School Trustees v. Quebec Bank (1915), Ontario Law Reports, 34: 624–32. Ottawa Separate School Trustees v. City of Ottawa, Ottawa Separate School Trustees v. Quebec Bank (1916), Ontario Law Reports, 36: 485–98. Ottawa Separate School Trustees v. Quebec Bank (1918), Ontario Law Reports, 41: 594–628. Ottawa Separate School Trustees v. Quebec Bank (1918), Ontario Law Reports, 43: 637–47. Re Ottawa Separate Schools (1917), Ontario Law Reports, 41: 259–75. Le siècle du règlement 17, sous la dir. de Michel Bock et François Charbonneau (Sudbury, Ontario, 2015). Esdras Terrien, Quinze années de lutte contre le Règlement XVII ([Ontario, 1970?]).

Cite This Article

Geneviève Richer, “GENEST, SAMUEL McCALLUM (baptized Marie-Joseph-Samuel),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/genest_samuel_mccallum_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/genest_samuel_mccallum_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Geneviève Richer |

| Title of Article: | GENEST, SAMUEL McCALLUM (baptized Marie-Joseph-Samuel) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 24, 2025 |