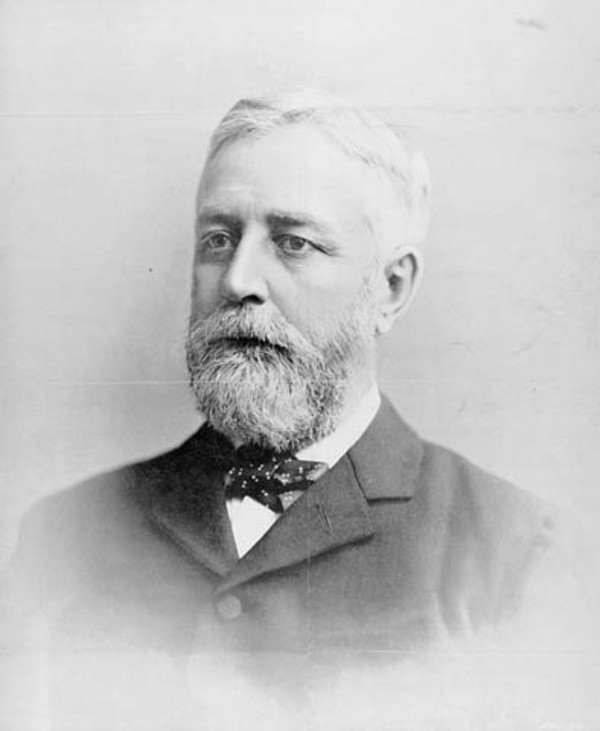

MEREDITH, Sir WILLIAM RALPH, lawyer, politician, judge, and educator; b. 31 March 1840 in Westminster Township, Upper Canada, son of John Walsingham Cooke Meredith and Sarah Pegler; m. 26 June 1862 Mary Holmes in London, Upper Canada, and they had three daughters and one son; d. 21 Aug. 1923 in Montreal and was buried in Toronto.

William Meredith’s father, a graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, who studied some law, had been preceded to the Canadas by other members of this notable Anglo-Irish family. He settled on a bush farm in Westminster in 1834. After William’s birth, he went to Port Stanley as deputy collector of customs and then to London as market clerk; in 1847 he was appointed clerk there of the Division Court of Middlesex County. This influential position, combined with successes in real estate, loans, and insurance, boosted the economic and social standing of the family, which became an important part of the town’s élite. The eldest son among 14 children, William was educated at the London District Grammar School and in 1856 he was articled to Thomas Scatcherd* of London. Three years later he won a two-year scholarship to the University of Toronto, where he studied law. Called to the bar in 1861, he entered into a partnership with Scatcherd that would last until the latter’s death in 1876.

Meredith took on a wide variety of civil and criminal cases and gradually became “the acknowledged leader of the London Bar.” In 1871 he was first elected a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada. Re-elected on many subsequent occasions, he received more votes than any other lawyer in the 1881 and 1886 polls, results that indicated the esteem in which he was held by his colleagues. He completed the requirements for an llb from the University of Toronto in 1872 and three years later he was made a qc by the provincial government, an honour that was repeated at the federal level in 1880. In 1876 he had succeeded Scatcherd as London’s city solicitor and from 1879 to 1888 he was first president of the Middlesex Law Association. In 1888 he left his practice in London to head the Toronto firm of the late William Alexander Foster*; that same year he became an honorary member of the law faculty of the University of Toronto, which granted him an lld in 1889.

Not completely satisfied with his legal attainments, in a by-election in 1872 Meredith had succeeded John Carling* as London’s representative to the Ontario legislature. There he joined the Conservative caucus on the opposition benches and embraced many of the values held by party leader Matthew Crooks Cameron*. Both men possessed a strong affection for Britain, the empire, and the Church of England, and they often displayed an “aristocratic temper.” Still, Meredith’s attitude led him to a sense of noblesse oblige that was not present in the more conventional Toryism of Cameron and other provincial Conservatives. In 1874, for example, only Meredith, Simpson McCall (a Conservative), and Daniel John O’Donoghue* (a labour mla) supported a motion for the unqualified enfranchisement of all males over 21, a measure that most Conservatives and all the Liberals considered too advanced for the times. Such stands have caused some to depict Meredith as a radical, but the appellation seems inappropriate for one who never challenged the basic assumptions of a society from which he derived so many personal benefits. Nevertheless, he was the first clearly defined progressive Conservative in Ontario.

Meredith’s tendencies did not prevent him from rising within a caucus thin in talent, and in 1878 Cameron named him deputy leader. Later that year Cameron became a judge and, when the assembly reconvened in January 1879, Meredith was chosen leader without even the formality of a ballot. In the hurried campaign for the election in June, he placed great stress on reducing public expenditure. The Liberal administration of Oliver Mowat* was indicted on some 29 charges of excessive spending. Though retrenchment never again achieved such pre-eminence in Meredith’s appeals – he would lead the Conservatives in four subsequent elections (1883, 1886, 1890, and 1894) – it remained a factor in his courting of voters. There were other regular features in Tory campaign literature. Meredith wanted to restore the power over liquor licensing that the province had taken from the municipalities under the Crooks Act of 1876. In addition, he called for a reversion to a non-partisan chief superintendent of education, a position Mowat’s Liberals had discarded in favour of a politicized minister of education. Meredith provided ample evidence to show that these moves had done much more for Grit patronage than they had for the public welfare. On one issue he was so conservative that he could be described as reactionary. Sexism was not unusual in the politics of the era, but in 1884 Meredith resisted not only the provincial franchise for women but also the municipal ballot for spinsters and widows and even a government measure to allow females to enter University College in the University of Toronto. In 1892 he sat on the Law Society committee that rejected Clara Brett Martin’s application to become a lawyer and in the assembly he was the most vocal opponent of the bill introduced by William Douglas Balfour* to require lawyers to interpret the word “person” in the society’s statute to include women.

These views were counterbalanced by the progressive component in Meredith’s political philosophy. He continued to fight for full male suffrage until it was accepted by the government in 1888, on which occasion the premier acknowledged his pivotal role. In 1884 he had chided Mowat’s administration for delaying the payment of annuities promised to many Indians and later in the session he fought unsuccessfully for an extension of the franchise to all adult male natives not living on reserves. The following year he introduced a workmen’s compensation bill modelled on British legislation. The Liberals incorporated the measure into one of their own bills in 1886 but Meredith objected to changes that he found too accommodating towards employers. He contended that the legislation should not have exempted corporations with voluntary compensation plans, since it would be impossible to determine whether private schemes could be as fair as the public design. In April 1887 Meredith was again more liberal than the Liberals in his response to the amendment of their factory legislation of 1884. To achieve proper enforcement – the key to success in this sphere – Meredith suggested that an inspector be appointed locally for every county. The government, however, would create only three inspectorships, to be filled by the province, for the whole of Ontario.

Meredith thus developed a balanced and seemingly attractive program, but it did not propel him to power. For one thing the Conservatives were weakly organized. Meredith viewed his job at Queen’s Park as a part-time commitment: he saw no need to call caucus meetings, oversee other responsibilities in the assembly, or attend to constituency business. Moreover, throughout his parliamentary career there was the distraction of a full-time legal practice. And to a considerable extent, Meredith’s lack of political success was a natural consequence of Mowat’s greater skills.

Electorally four main considerations account for the dramatic series of defeats experienced by the Conservatives between 1879 and 1894. First, Mowat’s Liberals freely stole many of their proposals. Journalist Hector Willoughby Charlesworth* would later note that “Mowat frequently rode to victory on policies that had originated with his brilliant opponent.” Secondly, Meredith’s platform held few inducements for rural voters. When he did focus on them, it was usually in a critical way. During the 1886 campaign, for instance, he claimed that it was grossly unjust to grant to farmers’ sons voting privileges that were denied to those of urban labourers. Such an approach, however logical and courageous, was politically unwise in a predominantly agricultural society. A third circumstance that cost Meredith votes was his relations with the federal Conservatives under Sir John A. Macdonald*. Meredith hoped for patronage from Ottawa to reward his supporters in Ontario, but little materialized. In addition, the hard line that Macdonald pursued in federal-provincial conflicts, such as the boundary dispute between Ontario and Manitoba, embarrassed Meredith and enabled the Liberals to charge that he was “disloyal” to the province.

Meredith’s growing frustration with the national leadership was, in part, responsible for his confrontation with the Roman Catholic Church over separate school rights, which furnishes the fourth reason for his political failure. In the belief that the Catholic vote in Ontario was pivotal, Macdonald forged an alliance with leading clerics, including archbishops John Joseph Lynch* of Toronto and James Vincent Cleary* of Kingston, to bring this bloc into the Tory camp federally. At the same time Mowat courted them to improve his position provincially. An isolated Meredith, who had always objected to the principle of separate schools, agreed with Macdonald that the Catholic vote was essential to political success in Ontario, but increasingly he felt that “humiliating concessions” were being granted to the Catholic minority by the Mowat Liberals.

In 1885, driven by conscience and Macdonald’s refusal to respond to his complaints, Meredith launched an attack upon what he saw as the unfair advantages enjoyed by the separate schools. He denounced the Catholics’ right to a guaranteed seat on all secondary school boards and the use of unapproved texts in separate schools. Later, he added to his list of grievances the need for compulsory balloting in separate school elections, which clerics had traditionally controlled, and for a more thorough introduction of English as the language of instruction in Ontario’s francophone separate schools. Meredith’s criticism appeared measured in comparison with the attacks of more extreme antagonists, such as the Toronto Daily Mail, but it was sharp enough to draw the wrath of the Catholic leaders. They threw their weight behind the Liberals, thus helping ensure decisive victories in the elections of 1886, 1890, and 1894. In 1891 efforts by the federal Conservatives to draw Meredith off the provincial stage and into the cabinet, to fill the Ontario seat left vacant by Macdonald’s death, had been vetoed by justice minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*, who, influenced by Catholic bishops in Ontario, found Meredith’s position on separate schools unacceptable.

As a result of the election of June 1894, there were no Catholics in the Tory caucus in Toronto [see Solomon White*]. This embarrassing state of affairs, combined with Meredith’s disheartening record of defeat, no doubt contributed to his acceptance of an offer from Ottawa to embark on a more promising career, in October, as chief justice of the Common Pleas division of the Ontario High Court of Justice. He had carefully maintained his standing as a lawyer; from 26 Feb. 1894 to 8 October he was corporation counsel for the City of Toronto and nominal head of its legal department. Knighted in 1896, he became chief justice of the province’s Court of Appeal in 1913.

Meredith acquired a high reputation and was considered by some to be “the ablest jurist in Ontario.” However, after examining 750 of his cases, legal historian R. C. B. Risk has concluded, in part because of their diversity, that Meredith had little opportunity to develop a coherent philosophy of law, except for a firm commitment to the doctrine of strict precedent. He would scour British, American, and Canadian judgements to discover decisions that seemed germane to the case at hand. If conflicting judgements appeared, he favoured the side with the most verdicts. Throughout the process his personal opinions counted for little: it was a judge’s responsibility to apply precedents, not create new ones. Meredith also sought to avoid injecting his views into decisions pertaining to statutes. When working with a law, he tended, impressively, to consider it as a whole along with its history, to determine the intent of the legislators, and to avoid narrow, restrictive interpretation. The statutes he considered most often were the Municipal Act and the Railway Act. With good reason Toronto city lawyer William Johnston would praise him in an obituary as “one of the best versed judges in municipal law.”

Within the courtroom Meredith was considered dignified and courteous, but he could also be “severe.” At times he appeared irritable and imperious. Barristers who were unprepared and or not properly informed about the law often received harsh reprimands. “His genial courtesy,” former justice Wallace Nesbitt confirmed, “always overbore a slight tendency to explosive indignation at anything which he conceived to be a technical rather than a justice-serving presentation of a case.” Meredith revelled in challenging colleagues to meet his exacting standards of legal argument and authority. Respected and affectionately known among his fellow judges as “the Chief,” he was a kindly man with “very few intimates” who turned privately to floriculture for recreation.

Despite his refusal to alter law through judicial proceeding, outside the court Meredith did exercise great influence politically, and his legislative and forensic skills were frequently enlisted by various governments. In 1896 and again in 1906 he excelled as a member of Ontario’s statutory revision commission. He also emerged as an important educator, having been chosen a senator at the University of Toronto in 1895 and its chancellor in 1900. In the latter position, which he would hold until his death, he was particularly forceful. His conversion of James Pliny Whitney*, his protégé in the legislature and premier from 1905, to the cause of university reform led to legislation in 1906 that modernized the administrative and financial structures of the University of Toronto. Whitney called on Meredith in 1906 to help prepare two other bills: to regulate railways and to establish the Ontario Railway and Municipal Board. The same year he reviewed and encouraged the legislation that initiated the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario. Whitney clearly valued Meredith’s advice, a pragmatic blend of conservative and progressive views. This role culminated in Meredith’s appointment in 1910 as a one-man provincial commission to investigate workmen’s compensation. The resulting bill of 1914 updated and made much more effective the existing measures in this field. In addition, Meredith, who chaired Toronto’s Civic Improvement Committee in 1909–11, was appointed to several other commissions. On the federal level, in 1912 he probed the collapse of the notorious Farmers Bank of Canada and four years later he investigated the awarding of questionable contracts by Ottawa’s Shell Committee during World War I. In Ontario in 1919 he looked into police matters and charges concerning the administration of the Ontario Temperance Act; in the latter enquiry his exoneration of licence inspector John Almayne Ayearst was denounced by Liberal leader Herbert Hartley Dewart. In 1921 he served on a committee struck by the United Farmers’ administration in Ontario to instruct it on the selection of king’s counsels. By this time his advice largely transcended partisan considerations.

Meredith remained active until an intestinal ailment, contracted while on holiday in Maine, occasioned his death in Montreal in 1923. Buried in St James’ Cemetery in Toronto, he left an estate valued at $133,877, including his home and gardens on Binscarth Road in Rosedale. He was survived by his wife, their three daughters, and seven distinguished brothers, including Sir Henry Vincent and Richard Martin, also a chief justice.

Sir W. R. Meredith’s main impact was felt in Ontario politics, where he formulated a progressive Conservative tradition which was inherited, and further developed, by Whitney and other Tory leaders. The éminence grise of the Whitney regime, he assisted in implementing many of the progressive concepts that he had vainly advocated while in opposition. As a jurist, Meredith was less ideological, but he was highly regarded by his colleagues on the bench as well as by the governments which eagerly sought his advice.

London Public Library and Art Museum (London, Ont.), Hist. ser. scrapbooks; London scrapbooks. NA, MG 25, 175 (mfm.); MG 26, A, Macdonald to O’Connor, 22 Feb. 1872; Meredith to Macdonald, 29 April 1879, 20 Oct. 1882; Lynch to Macdonald, 9 May 1882; D, Meredith to Thompson, 1 Oct. 1894. Daily Mail and Empire, 22 Aug. 1923. London Free Press, 29 April 1879. Mail (Toronto), 10 Jan. 1879, continued by Toronto Daily Mail, 3, 20, 23 Dec. 1886. Toronto Daily Star, 22–23 Aug. 1923. F. H. Armstrong, The Forest City: an illustrated history of London, Canada ([Northridge, Calif.], 1986). Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins), vol.1. Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), 1 (1923): 557–58. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. P. [E. P.] Dembski, “A matter of conscience: the origins of William Ralph Meredith’s conflict with Archbishop John Joseph Lynch,” OH, 73 (1981): 131–44; “Political history from the opposition benches: William Ralph Meredith, Ontario federalist,” OH, 89 (1997): 199–217; “William Ralph Meredith: leader of the Conservative opposition in Ontario, 1878–1894” (phd thesis, Univ. of Guelph, Ont., 1977). A. M. Evans, Sir Oliver Mowat (Toronto, 1992). C. W. Humphries, “Honest enough to be bold”: the life and times of Sir James Pliny Whitney (Toronto, 1985). J. R. Miller, Equal rights: the Jesuits’ Estates Act controversy (Montreal, 1979). National encyclopedia of Canadian biography, ed. J. E. Middleton and W. S. Downs (2v., Toronto, 1935–37). Ont., Legislature, “Newspaper Hansard,” 1867–86. R. C. B. Risk, “Sir William R. Meredith, c.j.o.: the search for authority,” Dalhousie Law Journal (Halifax), 7 (1982–83): 713–41. Toronto, City Council, Minutes of proc., 1894: 53, 61, 224; app.A: 51–52, 69. Eric Tucker, Administering danger in the workplace: the law and politics of occupational health and safety (Toronto, 1990). Types of Canadian women . . . , ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903).

Cite This Article

Peter E. Paul Dembski, “MEREDITH, Sir WILLIAM RALPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meredith_william_ralph_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meredith_william_ralph_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter E. Paul Dembski |

| Title of Article: | MEREDITH, Sir WILLIAM RALPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |