Source: Link

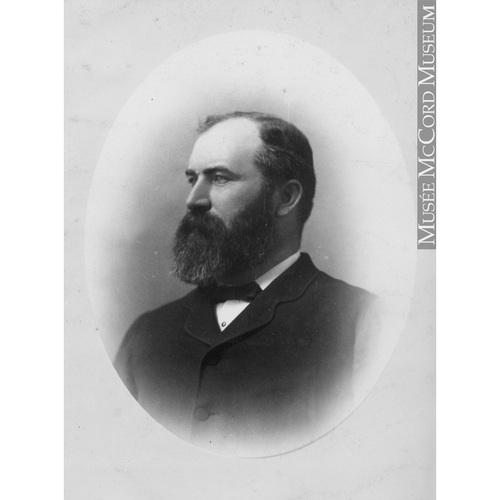

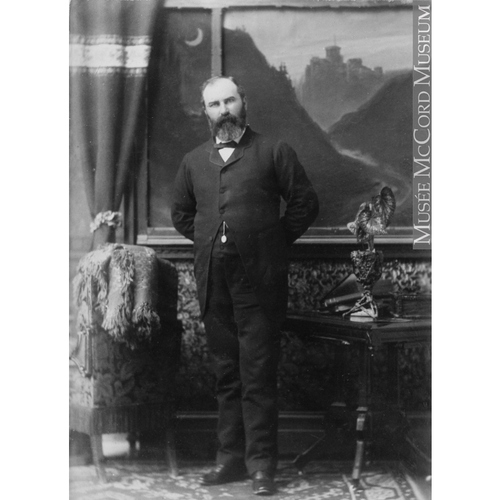

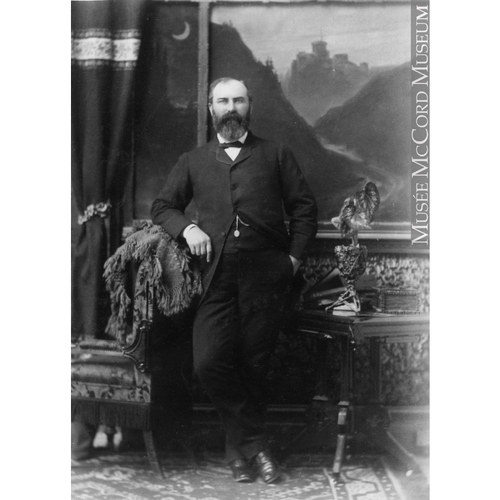

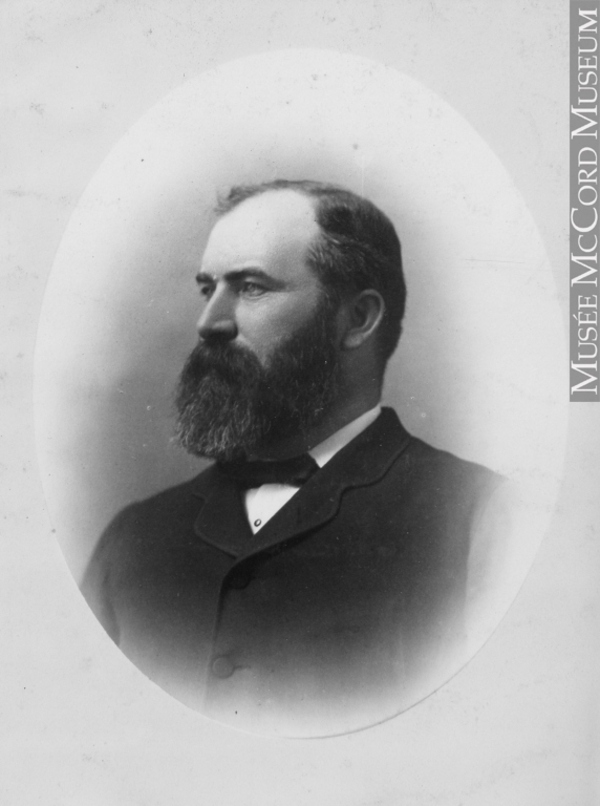

BUNTING, CHRISTOPHER WILLIAM, printer, businessman, journalist, and politician; b. 11 Sept. 1837 in Amigan, County Limerick (Republic of Ireland), son of William Bunting and Jane Crowe; m. 5 Nov. 1868 Mary Elizabeth Ellis, and they had five sons and a daughter; d. 14 Jan. 1896 in Toronto.

In 1850 Christopher William Bunting, his sister, and their widowed mother immigrated to Canada and settled in Toronto. Young Bunting had received schooling in Ireland, and in Toronto he attended St James’ parish school; his religious training was Methodist and Anglican. At about 14 he became a compositor with the Globe, edited by George Brown*. He served as foreman of the mechanical department and did some local reporting before leaving the journal in 1866. For the next 11 years he pursued a commercial career in wholesale groceries, first as a financial manager of John Smith and Company, next as a junior partner in John Boyd and Company, and then as a partner of Henry W. Bailey. In 1873 he moved to Clifton (Niagara Falls), where Bailey and Bunting specialized in importing sugar.

It is not certain when Bunting first made the acquaintance of fellow Irishman John Riordon*, a St Catharines paper-maker and millionaire, but in 1877 they brought off a coup by exercising Riordon’s chattel-mortgage rights over the Toronto Mail, hitherto a Conservative party organ. Riordon, with Bunting as junior associate, secured control of the Mail for practically nothing and Bunting was appointed managing director of the reorganized company. Riordon and Bunting agreed to continue running the newspaper as a Conservative journal, and Bunting even became a loyal and active organizer for the party. The opportunity provided him by the take-over, however, was to turn the Mail into a thriving enterprise.

Bunting employed new capital supplied by Riordon to challenge the dominant position of the Globe. Over time he hired talented young staffers to enliven the paper’s columns, among them Kathleen Watkins (Blake*), Philip Dansken Ross*, and Edmund Ernest Sheppard*. Though Bunting wrote editorials infrequently, he always maintained a close supervision over the news and editorial departments. He extended the news service. Together with William James Douglas, he also reorganized the business departments and purchased new presses. By 1881, when a new building was constructed, Bunting’s innovations had done their work: the Toronto Daily Mail achieved parity of circulation with the Globe.

On the political side, Martin Joseph Griffin (editor between 1881 and 1885) sustained the rigorously partisan editorial reputation of the Mail while Bunting cemented his ties to Sir John A. Macdonald by sitting as the Conservative mp for Welland from 1878 to 1882. In the latter year Bunting lost to Liberal leader Edward Blake* in West Durham. Macdonald sought, unsuccessfully, to secure him a seat in British Columbia. Bunting had emerged as one of the prime minister’s important advisers.

By 1882, however, his political priority had shifted to the defeat of Ontario’s Liberal premier, Oliver Mowat*. After the Liberals were returned in 1883 with a slim majority, Bunting explored the possibilities of luring away “loose fish” from the Liberal caucus. This was a dangerous strategy, for some of his indiscreet associates implicated Bunting in explicit offers of money. When this “bribery plot” was exposed in the legislature on 17 March 1884, Bunting faced the crisis of his career. His involvement might constitute criminal conspiracy and contempt of the legislature. He left the country in May for two months to avoid testifying before a judicial inquiry. In January 1885 it reported in the majority that the alleged conspiracy had existed. The minority report argued on technicalities that no conclusions were possible, and thus reduced the danger of legislative censure faced by Bunting. In criminal proceedings which concluded in April 1885, Bunting and his co-conspirators were found not guilty.

As early as 1883 Bunting had become convinced that to defeat Mowat it would be necessary for the Mail to appeal to the sentiments of the Anglo-Protestant majority, even at the expense of alienating Roman Catholic Conservatives. The aftermath of the North-West rebellion of 1885 [see Louis Riel*] moreover, reinforced Bunting’s conviction that not only provincial but national politics were being perverted by undue French, Catholic, and clerical influence. The shift of his anti-Catholic focus to include national politics represented a crisis for both the Mail and the Conservative party.

To make this Anglo-Protestant appeal Bunting had turned (probably in the fall of 1884) to a new editor, the gifted Edward Farrer*, on the recommendation of mp D’Alton McCarthy. For all the embarrassment the Mail caused Macdonald through 1886, Bunting initially remained loyal to the Conservative party. Whatever the motivations of Farrer or Charles Riordon*, his new senior associate since 1882, Bunting appears to have seen the “Protestant Horse” as the best policy for Conservatism in Ontario. At the same time this uncompromising anti-Catholicism promoted independence from the Conservative party which in turn enhanced the stature and influence of the Mail throughout the province. Bunting was seeking much the same thing as McCarthy: a realignment of the Conservative party around an Anglo-Protestant ascendancy. Macdonald continued to exhort Bunting to desist, but in the fall of 1886 the prime minister merely repudiated the views of the Mail on Catholic influence. Only in the wake of the Ontario election in December, which Mowat won with a large majority, did Macdonald resolve that there must be a public break. At his request the Mail formally declared its independence on 8 Jan. 1887.

The Mail then began to elaborate what its independence meant. To its strident calls to resist French and Catholic influence, the paper added support for commercial union with the United States. Along with other reform panaceas, the Mail endorsed prohibition of alcohol. In the summer of 1888 it seized upon the Quebec government’s Jesuits’ Estates Act [see Honoré Mercier] as a target for its concerns over French and Catholic “aggression.” Again it sought to lead public opinion in Ontario towards an assertion of Anglo-Protestant values and championed the Equal Rights Association, formed in Toronto in June 1889, as the agency for transforming Ontario politics [see Daniel James Macdonnell]. Other papers had experimented in editorial independence, but none had sustained its position so forcefully on the editorial page as did the Mail through Farrer. According to American critic Walter Blackburn Harte in 1891, Bunting had created the only “quality” morning daily in Canada to practise “independence.”

Not everything went according to the Mail’s script. Bunting found independence as frustrating as old party ties. In 1886 the Mail building had experienced a costly fire. The following year the Conservatives established a new official organ, the Empire, which undercut the Mail’s profits. Moreover, Bunting’s freedom of managerial action seems to have become more circumscribed under Charles Riordon. In 1889 the paper dropped commercial union almost as suddenly as it had picked it up in 1887. In the provincial election of 1890 Conservative leader William Ralph Meredith* tilted party rhetoric in the direction demanded by the independent Mail, but again Bunting had to watch as Mowat’s Liberals won. Then, in the summer of 1890, Farrer left for the Globe. By the federal election of March 1891 the opportunities to effect an electoral revolution in Canadian politics along the lines of Anglo-Protestant ascendancy had slipped away.

That fall Bunting initiated negotiations to reach an accommodation with the Conservative government in Ottawa and these were renewed in 1893. They culminated in another business triumph for Bunting. On 7 Feb. 1895 he secured the purchase of the Empire, possibly for as little as $30,000. Retaining control of the renamed Daily Mail and Empire, Riordon and Bunting rationalized the morning market for newspapers in Toronto and formed a new, official Conservative journal in a single stroke.

In a sense Bunting was back where he had started in 1877. He and his young editor, Arthur Frederick Wallis, were returning to party journalism. Yet this seeming reversion masked subtle changes. The Mail and Empire sought to interpret news for the Conservative party’s benefit no doubt, but it continued to insist on standards established during the Mail’s days of independence: an effort at comprehensive coverage and dispassionate editorial comment. It was no longer sufficient for a quality daily to be an organ parroting party leaders. Bunting, however, got no opportunity to supervise this development. By the fall of 1895 he was quite ill. He died of Bright’s disease at his Queen’s Park residence at the age of 58, less than a year after his brilliant merger of the Mail and the Empire.

Bunting is important for his failure to achieve a truly independent role as a journalist. His career reflects the inability of the last generation of Victorian journalists to discover a professional strategy wholly outside party influence. Notably, Bunting’s departure into independent journalism did not even address the issue of the professional rights and responsibilities for working journalists, by recognizing their role in defining the news or by creating mechanisms for them to exercise some freedom from their publishers. Still, Globe editor John Stephen Willison* observed in 1897, Bunting was “quick to know the public temper and able always to make a great journal respected and influential.” This was a start. The conscious effort to attract new audiences through a reputation for editorial integrity was part of a process which eventually gave newspapers, oriented to mass markets and the huge advertising revenues that went with them, the basis for a more authentic independence. In his brief experiment in such journalism, however abortive and however limited in scope, Bunting was a pioneer who helped to transform daily journalism into a profession. In his premature death he became a symbol for journalist ideals not yet realized.

NA, MG 26, A. UWOL, Regional Coll., Fred Landon papers, newspaper hist. scrapbooks, 2: 74. J. T. Clark, “The daily newspaper,” Canadian Magazine, 7 (May–October 1896): 101–4. W. B. Harte, “Canadian journalists and journalism,” New England Magazine (Boston), new ser., 5 (1891–92): 411–41. Ont., Legislature, Journals, 1884: 149–51, 154–57, 160, 198–99; Sessional papers, 1885, no.9. Daily Mail and Empire, 14 Jan. 1896. Globe, 14 Jan. 1896. Grip (Toronto), 1873–94. Mail (Toronto), 1877–80, esp. 23 Nov. 1877. Toronto Daily Mail, 1880–89, esp. 2 Aug. 1880, 14 Jan., 20 Sept. 1886, 8 Jan. 1887, 16 Feb. 1889. The Canadian newspaper directory (Montreal), 1892, 1899. CPC, 1879–81, 1883. Prominent men of Canada . . . , ed. G. M. Adam (Toronto, 1892), 222–25. B. P. N. Beaven, “A last hurrah: studies in Liberal party development and ideology in Ontario, 1875–1893” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1982). C. R. W. Biggar, Sir Oliver Mowat . . . , a biographical sketch (2v., Toronto, 1905), 1. George Carruthers, Paper-making (Toronto, 1947), 499–501, 510–12. H. [W.] Charlesworth, Candid chronicles: leaves from the note book of a Canadian journalist (Toronto, 1925); More candid chronicles: further leaves from the note book of a Canadian journalist (Toronto, 1928). A history of Canadian journalism . . . (2v., Toronto, 1908–59), [1]. J. C. Hopkins, “Toronto; an historical sketch,” Toronto, Board of Trade, “Souvenir”, 3–113. J. E. Middleton and Fred Landon, The province of Ontario: a history, 1615–1927 (5v., Toronto, [1927–28]), 1: 409. C. P. Mulvany, Toronto: past and present; a handbook of the city (Toronto, 1884; repr. 1970), 192. Rutherford, Victorian authority. G. R. Tennant, “The policy of the Mail, 1882–1892” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1946). Waite, Man from Halifax.

Cite This Article

Brian P. N. Beaven, “BUNTING, CHRISTOPHER WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bunting_christopher_william_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bunting_christopher_william_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian P. N. Beaven |

| Title of Article: | BUNTING, CHRISTOPHER WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |