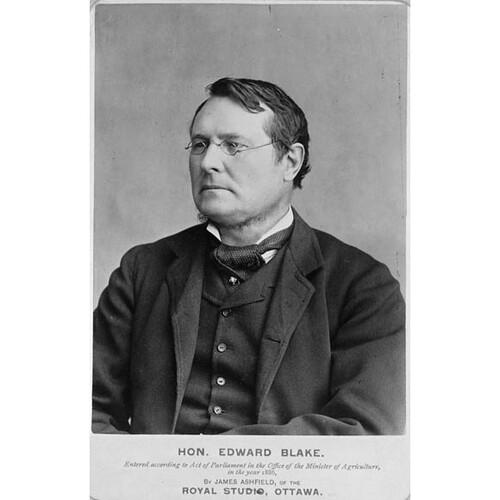

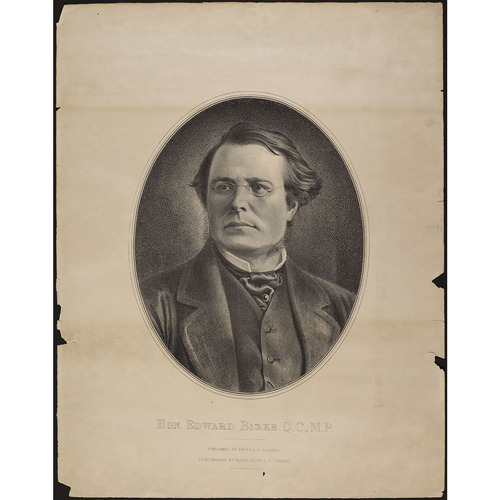

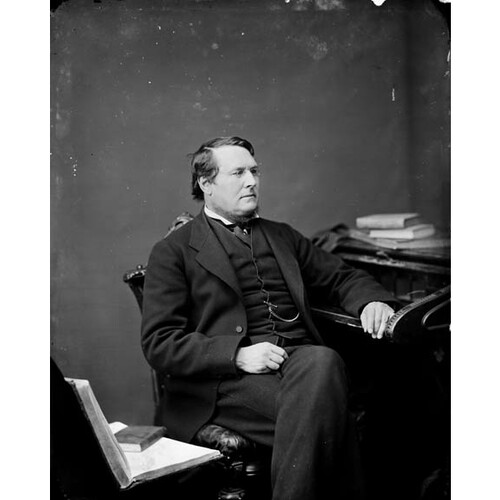

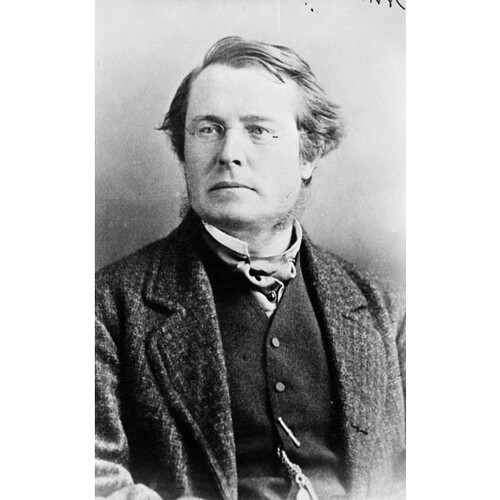

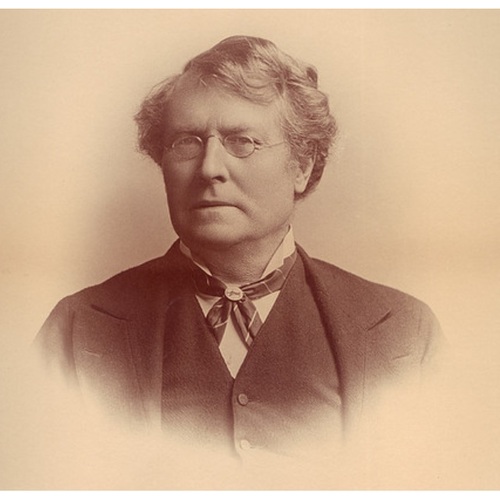

BLAKE, EDWARD (baptized Dominick Edward), lawyer and politician; b. 13 Oct. 1833 in Adelaide Township, Upper Canada, son of William Hume Blake* and Catherine Honoria Hume*; m. 6 Jan. 1858 in London, Upper Canada, Margaret Cronyn (d. 1917), daughter of Bishop Benjamin Cronyn*, and they had three daughters, of whom two died in infancy, and four sons, one of whom died in infancy; d. 1 March 1912 in Toronto.

Edward Blake belonged to an intensely evangelical Anglican family; his mother in particular was rigid and oppressive in this regard. The family was also extremely close-knit: Blake’s father and mother were cousins (his paternal grandfather had also married a Hume cousin), and they had immigrated to Upper Canada from Ireland in the company of relatives and friends, including Dominick Edward Blake* and Benjamin Cronyn. Blake was born in a log cabin during his father’s ill-advised phase as a backwoods farmer on Bear Creek (Sydenham River), in the portion of Adelaide that later became part of Metcalfe Township. His early years were spent in Toronto, where his father would achieve success as a lawyer, Reform politician, and judge. Edward and his younger brother, Samuel Hume, were for a time educated at home by their parents. This teaching was supplemented by tutors, even after Edward had entered Upper Canada College in 1846. He internalized family pressures to succeed academically and became an autodidact, an approach that would serve him well in his legal and political careers. William Hume Blake generated a wake for Edward to follow in and incentives to excel; moreover, the father’s financial difficulties after 1857 created a powerful drive in the son to achieve monetary security. And the family remained close: in 1859 Edward and his wife would move in with his parents in their new farm residence north of Bloor Street, Humewood.

According to his mother, Edward had been a desultory student at Upper Canada College until his last year. He became head boy in 1850, won a variety of prizes, was highly thought of by his teachers, and emerged as a strong intellectual. Following graduation from the University of Toronto (ba 1854), he was articled to his father’s former law firm, A. and J. Macdonnell. Admitted as an attorney during Trinity term in 1856, he opened his own practice on 14 June 1856, entered into partnership with Stephen Maule Jarvis in August, and was called to the bar during Michaelmas term. Blake found Jarvis lax in collecting debts and parted company with him in July 1857.

After a slow start, his legal business, most of it in equity, grew rapidly. Between 1857 and 1867 Blake was involved in 214 cases in the Court of Chancery alone, an extraordinary number that reflected a life of hard work. He took his brother into the firm in December 1858 and made him a full partner in 1862, the same year that he added Rupert Mearse Wells and James Kirkpatrick Kerr. In 1861 Blake’s prestige was such that he became a lecturer in equity for the University of Toronto and the Law Society of Upper Canada. Three years later he was appointed a qc, possibly through the lobbying of fellow Reformers Oliver Mowat* and George Brown*. He was denied the status of bencher by the law society in 1866, a move that drew protest from his peers; it was later discovered that he had been thought to be too young. Advancement was not long denied, however: he would become a bencher in 1871 and treasurer of the law society in 1879. Such was his legal success that, when he entered electoral politics in 1867, he could publicly claim independent wealth of over $100,000, an astonishing sum for a man of 33.

Blake’s Reform, liberal, and religious outlook had initially been fostered in the family circle. Perhaps his wanderings in Paris with his father during the revolution of 1848 (shortly after Edward had obtained glasses to correct his severe short-sightedness) had helped establish an attachment to social change. It was the law, however, that was crucial in shaping his liberalism. In one defining case he joined lead counsel Adam Wilson* in challenging the constitutionality of the “double shuffle” in the Conservative cabinet of George-Étienne Cartier* and John A. Macdonald* in 1858 [see William Henry Draper*]. In this case, against crown lands commissioner Philip Michael Matthew Scott VanKoughnet* in the Court of Queen’s Bench, Blake argued with great moral conviction that “no man being a member should be placed in power without being sanctioned by the people.” His rhetoric reflected his deep liberalism, and the case provided the young lawyer with a useful measure of public notoriety. On 20 Nov. 1858 the Globe announced that he had demonstrated “great oratorical powers” and revealed the potential “to take his father’s place at the bar.”

Two other causes helped define his outlook over the next few years. In 1863 Blake, who had earned an ma in classics from the University of Toronto in 1858, joined Adam Crooks* and other graduates in its senate in rejecting the recommendations, backed by education superintendent Egerton Ryerson*, to divide much of the government funding for the university among the denominational colleges in Upper Canada. This victory, an assertion of an essentially secular university, reaffirmed Blake’s status as a rising Reformer and public figure: here was one who would search for fairness and conscience. Again with Crooks, Blake was counsel in 1864 to his father-in-law, the bishop of Huron, in a challenge to the authority of Bishop Francis Fulford*, first metropolitan of the ecclesiastical province of Canada. Blake and Crooks questioned the legality of Fulford’s call for a provincial synod without the voluntary concurrence of the dioceses. Striking in this challenge, as it related to Blake, was the nexus of his deeply held religious perspectives, his belief in representative government, and his rejection of unreasoning authority.

These and other cases made Blake a politically marked man, and, in turn, his firm’s prosperity allowed him to become involved in politics. As well, his parents, whose wishes were a decisive consideration, urged him in that direction. He had been rumoured to be a candidate for the position of solicitor general in John Sandfield Macdonald*’s pre-confederation ministry. “As a lawyer he is admirable – excellent common sense, immense industry and great pluck. . . . Not much of a politician, but anxious to learn & as sharp as a needle,” George Brown noted in March 1867. Blake was thus recruited to play a role at the seminal Reform Convention in June, and to run that summer for seats in the provincial Legislative Assembly (Bruce South) and the federal House of Commons (Durham West). He won both ridings, but the Bruce victory was tainted by dubious expenditures; the stress Blake felt between principle and practicality found sharp vent as he threatened to resign the seat. That he did not was perhaps a sign of the prevarication of which he was eminently capable.

Blake’s entry into politics enhanced his standing in the legal profession. In 1868 Sir John A. Macdonald, then prime minister, tried to recruit him as a judge. Macdonald wanted to move VanKoughnet from the head of Chancery to Queen’s Bench, to replace Chief Justice William Henry Draper, and then put Blake in his position. The plan fell through when VanKoughnet refused, but his death a year later reopened negotiations. Blake saw Macdonald’s motivations as political, and rejected the position.

A coming but unseasoned politician, Blake quickly proved himself one of a handful of leaders in the federal Reform group, and was consulted on all major policy and organizational questions. However, it was at the provincial level that his first great chance developed. In 1869, to protest the “better terms” granted Nova Scotia by the federal government [see Archibald Woodbury McLelan*], Blake introduced into the assembly a series of resolutions opposing any alteration of the terms of the British North America Act without prior consultation with all the provinces. Here he articulated a view of provincial rights that Mowat would later elevate to new heights. As a result of such initiative, Blake was viewed as a potential leader of the opposition to the Sandfield Macdonald government, even by Archibald McKellar*, who held the post until 3 Feb. 1870. Shortly after he took over from McKellar, Blake’s next opportunity arrived, with the resistance led by Louis Riel* in Red River (Man.) and the death there of Orangeman Thomas Scott*, which roused powerful emotions in Ontario. By homing in on the legal issue of murder or execution in Scott’s death, he played to the public’s baser instincts without dabbling in them directly [see Sir Matthew Crooks Cameron*]. The issue undermined the government, even though Sandfield Macdonald hung on to power through dubious means after the election of March 1871. For a time he avoided calling the assembly into session, and once he did, he ignored votes of no-confidence. His behaviour prompted Blake, who had been re-elected in Bruce South, and fellow mla/mp Alexander Mackenzie* on 18 Dec. 1871 to mount a final, successful attack over the issue of parliamentary supremacy, combined with back-room machinations that Blake deplored but knowingly permitted.

By the 20th Blake was premier, with the attendant responsibilities of forming a cabinet and preparing a legislative agenda. He recruited Mackenzie first as provincial secretary and registrar, and then induced him to switch to treasurer. For balance, given the continuing tensions created by the Scott affair, Blake persuaded the Catholic, Conservative-leaning Richard William Scott to act as commissioner of crown lands. McKellar was rewarded as commissioner of agriculture and public works, and Adam Crooks became attorney general. Amid numerous bits of housekeeping legislation and the incorporation of railways, waterworks, and the like, the Blake administration brought into law a significant reform program. Internal operations of the assembly were improved, reforms relating to the holding of seats were enacted, an act for the prevention of corrupt practices at municipal elections was passed, dual representation was abolished for Ontario, the budget improved social welfare on a narrow front, teachers’ pay was increased, an act extending the property rights of married women was passed, and the functioning of the courts was altered. In the dominion election of 1872 Blake was returned in Bruce South, but the abolition of dual representation required him and a handful of others to choose between federal and provincial politics. With George Brown and Alexander Mackenzie he persuaded Oliver Mowat to leave the bench and become premier in October 1872, thus freeing himself for dominion politics.

In March 1873 the federal Reformers settled on Mackenzie as their leader. It seems likely that if Blake had wanted the position it could have been his, but he begged off. Mowat’s return to politics had led Sir John A. Macdonald to appoint Samuel Blake to a vice-chancellorship in the Court of Chancery, leaving the Blake firm in some disarray. Edward’s own nervous debilitation in the latter half of 1872, the death of an infant daughter, and the drawn-out consequences of his father’s death in 1870 had led to his retreat from provincial politics and his unwillingness to undertake direct leadership at the federal level. Thus, while he fully participated in the massive assault on the Macdonald government over the Pacific Scandal, an attack that let him exercise his powerful forensic skills and sense of moral outrage to the full, it was Mackenzie whom Governor General Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*] asked to form a new government in November 1873. Blake felt, perhaps only in retrospect, that he might have been asked. The failure to take on the Reform leadership in March 1873 was the premier error of his political career.

The next five years were to be tumultuous. Blake’s personal problems, not unlike his father’s, reached crisis proportions during his fifth decade. A sense of justice had balanced his religious uncertainties, but now secular salvation through the law seemed as unavailable as religious salvation through a conversion experience. He was prey to bouts of anxiety over his social and political isolation, yet he applied to himself rules that made loneliness in the political world likely. These peculiarities, linked with immense overwork caused by his renewed emphasis on private practice and by his political responsibilities, would result in repeated rounds of exhaustion, often accompanied by severe headaches. Neurasthenia, as it was called, was a state of extreme nervous debilitation, which left him incapable of work. Aficionados of gossip such as Dufferin believed that this complaint had ruined and killed Blake’s father, and that it lay like a doom over Blake. In combination with political considerations and rigid principle, the condition would lead to a number of his threatened and actual resignations from positions of authority.

Blake was reluctant to take political office in November 1873, in part because of his personal problems but also because he regretted having been passed over as prime minister. His eminence made it difficult for him to remain outside the cabinet, however. Mackenzie recognized that his inclusion was vital, and he bent much effort to recruit him. Under such pressure Blake became a minister without portfolio, an acceptance that required his intense commitment to campaigning in the general election of January 1874. He resigned from cabinet the following month, “the elections having proved,” in Dufferin’s words, “that his friends were strong enough to stand without him. Mr. Blake’s health is precarious, – he is making a considerable fortune at the Bar, and his nature is too sensitive for public life.”

In June Mackenzie tried unsuccessfully to bring him back. However, after Blake’s legal firm regained its footing following the departure of Samuel Blake, a combination of public pressure, personal dissatisfaction with the program of the government, and a resurgence of confidence led him to reconsider the cabinet and even the prime ministership. The public pressure came in part through the nationalist Canada First movement [see William Alexander Foster*]. Blake knew a number of the Canada Firsters, whose soirées he attended, and he had played into the rabid intensity of their campaign to punish Riel for the death of Thomas Scott. Blake’s reform agenda also had commonalities with that of the Canada First group. Goldwin Smith*, who was closely linked to it, viewed Blake as an appropriate instrument of reformist nationalism and encouraged him in his leadership aspirations, support that was supplemented by Blake’s following in parliament.

Blake was especially concerned with the Pacific railway and Mackenzie’s drift toward accepting the onerous terms urged in August 1874 by the British colonial secretary, Lord Carnarvon. Pressed by Carnarvon and Dufferin to yield on the railway, Mackenzie was ill with fatigue and was unsure of his powers of leadership, conditions that Blake was fully aware of. Blake, his latent leadership ambitions fired by opportunity, audaciously suggested in a letter of 6 September that Mackenzie give up the prime ministership and hold only Public Works, with Blake taking over the top post. Mackenzie responded by indicating that he would have to leave both government and parliament should he step down from the prime ministership. Blake backed off. The crisis was complicated by his deeply held suspicion, not assuaged until mid October in a correspondence with Mackenzie, that Mackenzie had kept him out of the prime ministership through misinformation after Macdonald’s resignation.

These exchanges with Mackenzie formed the context of Blake’s famous speech at Aurora, Ont., on 3 October, and they indicate why it was viewed as a direct challenge to the Liberal leadership. Blake’s rigid ethics prevented him from making the speech as part of an intrigue to remove Mackenzie or break the party, so he gave it without consulting the Canada Firsters, his parliamentary allies, or his friends. He could not prevent himself from making snide references to Mackenzie and the Liberal government before an audience that he estimated was over 2,000. More profoundly, discontent with existing political conditions was his text. Over the course of an hour and a half he eloquently propounded an expanded franchise, some form of proportional representation, compulsory voting, imperial federation, and Senate reform. The apparent trend of the government to yield ground on British Columbia’s railway demands brought him to apply some of his finest rhetorical excesses to that province, that “sea of mountains” with which a deal approaching “insanity” had been struck by the Macdonald government. His intense nationalism, framed within vague notions of imperial federation, led him to call Canadians “four millions of Britons who are not free.” Such phrasings had enormous appeal and the speech was widely published. Blake furthered his reform cause by financing, with Smith, the Liberal newspaper, which ran for a few months in Toronto in 1875 under the direction of John Cameron*. It was the Aurora speech, however, that received the widest attention: public reaction to it threatened party stability and made Blake’s recruitment into the cabinet vital.

Through third-party negotiators, Blake was finally lured into the Department of Justice on 19 May 1875, following the débâcle of Télesphore Fournier*’s stint as minister. Occurring at the end of drawn-out talks in which Blake declined the chief justiceship of the newly created Supreme Court of Canada, his appointment raised him to a central place in Canada’s legal and political world. He would furnish the cabinet and the government with legal advice, review all federal and provincial legislation, supervise federal penitentiaries, administer the royal prerogative in regard to capital punishment and the remission of sentences, and nominate candidates for the bench. Despite the status, Blake’s stay as minister was hardly happy since he was now subject to the sort of criticism he could so readily apply when outside government. When, for instance, near the end of his term he received a letter characterizing a judicial appointment as “designed & offensive,” he responded impatiently. “Speaking for myself I took office with reluctance, I will have it with pleasure, & while I am obliged to hold it my effort will be, as it has been, to do the thing that is right according to my lights. I may err in judgment, but I hope not in intention.” As well, he discovered the difficulties of implementing pure principle in the context of the legally correct, the constitutionally justifiable, and the politically advisable.

Blake was responsible for nominating the first members of the Supreme Court in early September 1875. While he proceeded, news came that the British law officers harboured doubts about the Supreme Court Act, especially clause 47, which terminated appeals from the court to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in England but still allowed appeals based on the royal prerogative. The imperial officers, including Lieutenant-General Sir William O’Grady Haly*, who was acting as administrator in Dufferin’s absence, thought the matter should be resolved before the court was constituted. Mackenzie wanted to press ahead; on 25 September Blake wrote that “to pause now would be ruinous. If judges not appointed or if bill afterwards disallowed I must resign.” Blake and Mackenzie won out, with the imperial officers agreeing not to disallow the act on the understanding that the clause did not, in the end, prevent appeals. Blake then constructed a memorandum outlining the Canadian perspective on the court. As Blake increasingly recognized, any limitation of appeals was problematic because appeals based on the royal prerogative were still retained. Clause 47 accomplished little, he had admitted in a letter to finance minister Richard John Cartwright on 7 October, the day before the court’s justices were sworn in.

In addition to clause 47, Blake had to confront the Colonial Office on the matter of disallowance of provincial legislation, especially when the dominion acted on the grounds that a province was moving beyond its competence. Such disallowance, Carnarvon felt, could potentially redefine provincial jurisdictions out of existence. His solution, announced in November, was to allow the governor general to reject the advice of his ministers in cases of disallowance, and assert that they were not obligated to resign after such rejection. Responding for the government on 22 December, Blake vigorously argued that the Colonial Office was ignoring responsible government. Not only did the BNA Act provide for disallowance through the “Governor General in Council,” it also fixed the constitutional underpinning, that the governor could act “only under the advice of his Ministers.” There was no middle ground. This powerful argument, rooted in the heart of reform tradition, exhibited Blake’s liberal nationalism at its best, and gave theoretical depth to real jurisdictional problems that came before him as minister. In 1876, for example, he had British Columbia’s second County Court Extension Act disallowed [see Sir Henry Pering Pellew Crease*] while in Ontario and Quebec he faced evolving jurisdictional questions over escheats.

On 3 June 1876 Blake launched a mission to England to present the Canadian position on a number of outstanding concerns, including the Supreme Court, the governor general’s instructions, and extradition between Canada and the United States. The mission was a distasteful exercise for Blake: it involved an implicit acknowledgement of Canada’s colonial status, he found lobbying unpalatable, and he was forced to recognize that practical political considerations in Britain took precedence over his liberal constitutional arguments. Yet his abilities were adequate to the tasks. He manoeuvred successfully to have the Supreme Court Act remain operative, though clause 47 was left without effect. The question of the governor general’s powers to refuse federal disallowance was also resolved, even though Lord Chancellor Hugh McCalmont Cairns was unwilling to concede all of Blake’s arguments concerning dominion rights and responsible government. The problem of extradition remained unresolved; Blake suggested that Canada might be forced to make its own extradition treaty arrangements – a renewed expression of his nationalist tendencies. He left to come home in August. Overall the trip was a disappointment, and its lessons undoubtedly compelled him to reconsider his place in Canadian politics.

The tensions of political life told on Blake. He had become embroiled in public controversy in October 1875 over the continuation of his law practice while he acted as minister. The episode started at a banquet in Montreal, where Sir John A. Macdonald suggested that Blake was neglecting his duties in favour of his practice. Particularly painful for Blake were newspaper accusations of his conflict of interest in appearing before judges whom he could promote and whose salaries he could alter. He was further hurt by the Globe’s assertion that his salary should be increased to compensate for any losses in his private income. Such a proposal, the over-sensitive Blake believed, meant that he was to be “bought off from practice.” As a result, in November he once more came close to resigning from cabinet, but Mackenzie persuaded him to stay. In terms of his private practice, he did take steps to address the controversy by negotiating a new partnership agreement. Dated January 1876, it stated that he would “retire temporarily” but would retain a share of the assets and profits.

The stress and the conflict between principle and practicality, especially his growing qualms about the possibility of pure justice, conspired again to make him consider leaving the government after his return from Britain in 1876. While he was in England, his duties had been shouldered by Albert James Smith*, who had affirmed death sentences for John and James Young in the murder of Cayuga farmer Abel McDonald the previous year. Blake’s reversal of these sentences on his return raised a furore. Once again he decided he had to resign, and he wrote to that effect to Mackenzie on 25 September, expressing his fundamental concern. “I am not apprehensive of attacks in Parliament, but I see that in the present state of things there is a danger that human life may be taken when it should be spared, and the consequences which may flow from a murderer’s hurried death are too awful to contemplate.” From one man of strong religious belief to another, the meaning was clear.

Blake was induced to remain, but he demanded that if he ever again submitted his resignation, it should be accepted without question. The systematic Blake was also offered the prospect of undertaking administrative reform in government, which he then embarked upon, with limited success. The changes he introduced followed in the stream of the government’s many regulatory reforms, reminiscent of Blake’s legislation as premier of Ontario. Among these regulatory reforms were the Collection of Criminal Statistics Act of 1876 and the Weights and Measures Act of 1877, both of which came with his imprimatur. The daily administration of business in his department continued to press him because of staff reductions, though the complication of the failing health of his deputy minister, Hewitt Bernard*, had been resolved through Bernard’s resignation in August 1876 and his replacement by Zebulon Aiton Lash.

These strains were compounded by the ongoing issue of the Pacific railway. Blake had expressed unrelenting hostility to a fiscally irresponsible railway deal with British Columbia. The Carnarvon Terms of 1874 and their potential acceptance had encouraged him to strike out with the Aurora speech; continuing pressure from British Columbia, the imperial government, and the excessively wilful Dufferin helped bring Blake to the edge of collapse. A tour of British Columbia had left Dufferin morally committed to a generous treatment of the province, and he took to bullying Mackenzie and Blake, with whom he “nearly came to blows” during a meeting on 18 Nov. 1876. Mackenzie might well have given way had not Blake, with Cartwright’s backing, stiffened his resolve. Though tempers cooled and Carnarvon removed himself from the controversy, the overworked Blake was visibly wounded.

Consistent with the nature of neurasthenia, his health deteriorated as pressures and expectations increased. The severe headaches had returned by October 1876, even before the confrontation with Dufferin; four months later Blake was “close to nervous exhaustion.” He abruptly informed Mackenzie on 30 April 1877 that he could no longer continue as minister. Despite their previous understanding that this resignation would be accepted, Mackenzie protested, and Blake agreed to undertake routine departmental matters for a few weeks longer. At this point, in May, the conciliatory Dufferin (with authorization from Carnarvon) offered both Blake and Mackenzie knighthoods, which they turned down on egalitarian – liberal – principle. For Blake the hope of a quick release from his duties was stymied by difficulties with the re-election of Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme*, who was to replace him, so it was not until Laflamme became minister on 8 June that Blake could leave and enter calmer waters as president of the Privy Council. Having finally freed himself, he left for the family retreat at Murray Bay (La Malbaie), Que., where, on this occasion as on many others, he hoped to regain his health.

Even the Privy Council proved too much. Although Mackenzie was reluctant to let him go, Blake resigned on 11 Dec. 1877, the same year that his eventual protégé, Wilfrid Laurier, had entered cabinet. In the election that Mackenzie called for September 1878, Blake reluctantly agreed to run again in Bruce South. Too debilitated to campaign, he instead travelled to Europe with his wife. In the overall defeat suffered by the Liberals, he lost his seat.

Blake’s departure from Justice had brought to a close an important phase of his legal career. Legal logic was unassailable, he had long maintained, and he had hoped that rational reform could mould society, government, and the law. In contradistinction, his political experience demonstrated how rational liberalism had to be framed within the context of expediency. This lesson confirmed his growing moral uncertainties about the exactitude of human justice, incertitudes that profoundly affected him on the occasions he was offered judicial posts. Taking a judgeship would have fulfilled familial ambitions, but human judgement, he had come to realize, was often as frail as it was final. Thus he had refused the chancellorship of Ontario in 1869 and the chief justiceship of the Supreme Court of Canada in 1875, and he would turn down judicial appointments in the future. Blake’s personal agonies scored all aspects of his life, though there perhaps remained a belief that, should he be prime minister, some of the constraints he had faced as minister of justice would be relieved.

For some months after the election of 1878, Blake was utterly absent from politics, channelling his energy instead to his “carefully systematized” practice, one of Toronto’s dominant law offices. According to a contemporary description, “partners varying in number at different times from four to six together with a numerous staff of clerks, were found barely sufficient to keep pace with the great and ever-increasing grist that came to the legal mill” headed by Blake. By 1879 he had taken up residence on Jarvis Street, closer to his offices at Adelaide and Victoria. Politically, Blake and Mackenzie, the latter still Liberal leader, were hardly on speaking terms, in part because Mackenzie had tried unsuccessfully to get Harvey William Burk, the Liberal mp for Blake’s old riding of Durham West, to step aside for the defeated Cartwright. Blake was mortified that, for Mackenzie, Cartwright’s re-election was paramount. It was not until 18 Nov. 1879 that Blake was re-elected by acclamation in Durham West, which had been vacated by Burk, but not through Mackenzie’s doing. Although Blake had in mind a direct challenge for the party leadership, there is no evidence that he plotted to this end. Isolated from his party and stunned in March 1880 by the death of Reform veteran Luther Hamilton Holton* and the shooting of George Brown, Mackenzie was vulnerable to Blake’s demonstration of leadership on the debate over the publicly funded construction of the Pacific railway. Under pressure from a caucus that looked to a rejuvenated Blake, Mackenzie resigned on 29 April 1880 at 2:00 a.m. and Blake became leader in caucus later that day. He would be re-elected in Durham West in 1882 and again in 1887, his last year as leader.

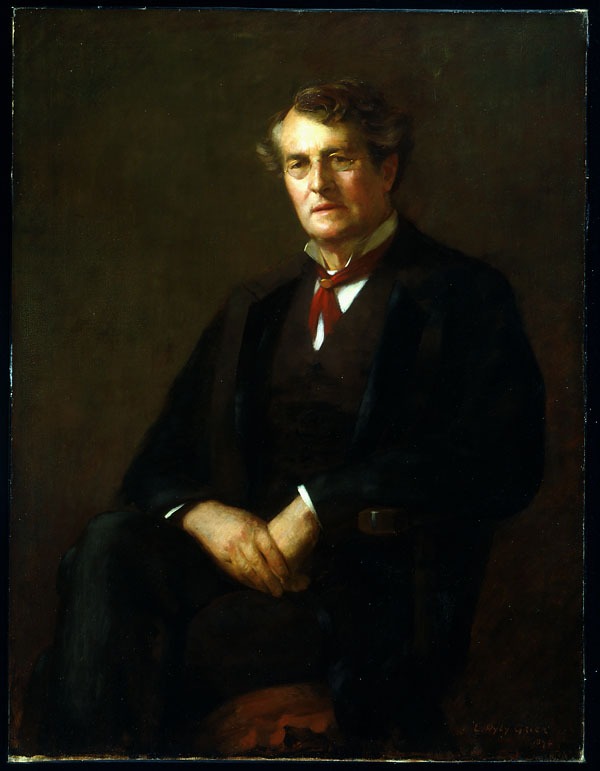

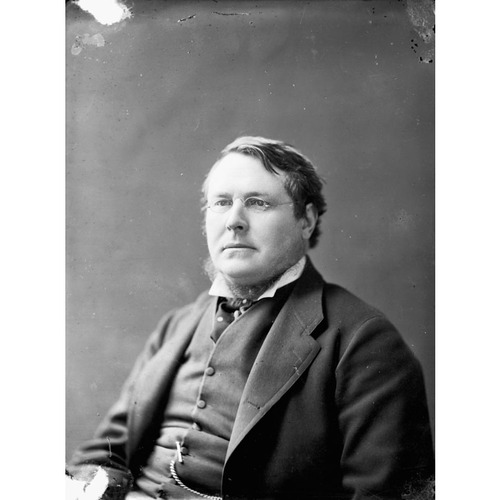

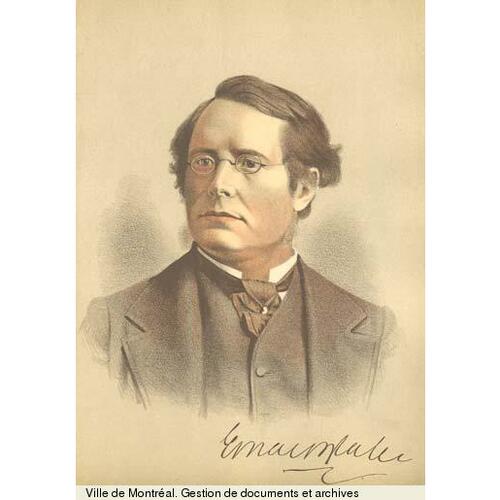

Blake’s physical characteristics made him a commanding figure. In health and maturity he was tall, broad-shouldered, and somewhat round-faced. He stood out in a crowd. The small, gold-rimmed glasses he wore emphasized the fullness of his face, which was fringed for some years by a scraggly beard. His voice was powerful but his oratorical abilities varied: when he was at his best, his devotion to truth, as defined by his introspective, analytical intelligence and his dedication to justice, made him compelling; when he felt it necessary to articulate fully his reasoning and evidence, his speeches became long, convoluted, and boring. His manner as a public man was also uneven. His store of good-humoured small talk and easy friendship was not large, though in fairness it must be said that his chief associates, such as Cartwright and Mackenzie, were no masters either. Introspection and poor eyesight caused Blake inadvertently to snub his colleagues and supporters, and sometimes his intellectual arrogance made snubs intentional. He was no politician; he led by pure ability.

Blake’s demoralized Liberals required organizational and policy leadership aimed at expanding their appeal while maintaining traditions. The organizational task, made more difficult by the loss of control of patronage in 1878, was necessary not only for electoral gain but, Blake felt, for the reduction of corrupt politics. He had an array of organizers to work with, among them James David Edgar*, William Thomas Rochester Preston*, and David Mills*, but he faced inertia and resistance at the constituency level. None the less, a network of Young Men’s Liberal clubs was expanded into a national body in the 1880s, the Ontario Reform Club was established at Toronto in 1886 under Cartwright’s presidency, the use of conventions became more entrenched, and a central party mechanism, including limited financing, emerged. All bore witness to Blake’s concerns about what, to him, was an underdeveloped but distasteful side of politics.

Blake recognized that his party faced serious difficulties in recruiting Roman Catholic voters in Ontario and Quebec due to embedded Grittish fears of French Canadian, Catholic domination – fears that Blake himself had once pandered to. His attack in 1884 on the bill to incorporate the Orange order, long allied with the Conservatives, proved a useful tactic in attracting Catholic voters. Though he explicitly denied that he was representing his party, his position disturbed many Ontarian Liberals. Blake also vigorously criticized Britain’s role in Ireland. His inclinations as an equity lawyer, his liberal imperialism, and the tensions inherent in his family’s Irish background thus found expression in an appeal to Canadians of Irish Catholic background. His attack on absentee British landlords, intended to secure Irish votes in Canada, created the basis of his later recruitment to the Irish Nationalist cause.

Quebec was more intractable. Although resurgent ultramontanism there was being defused, Louis Riel’s renewed activity in the Saskatchewan country in 1884–85 sparked smouldering tensions. Blake had already attempted to reduce intra-party stress by forcing the Grittish John Gordon Brown from the editorship of the Globe in December 1882. Riel’s conviction on grounds of treason and his execution on 16 Nov. 1885 nevertheless confronted Blake with his own harsh stance of 1870. In Quebec, on the Riel issue, he was largely dependent on Wilfrid Laurier and, less certainly, on Honoré Mercier*, who distanced himself from the party after Riel’s death. All of Blake’s moral, legal, and political uncertainties convened in his contemplation of Riel, so when he finally took a public position in early 1886, it was precisely equivocal: Riel had engaged in treasonous activity, but he was insane. This conclusion avoided further alienation of outraged Quebec sentiment, though it disappointed those of Blake’s Ontarian followers who fondly remembered 1870 and who undermined Blake’s position in the commons on the issue. In March the Liberals divided on the motion of Conservative Philippe Landry condemning Riel’s execution. Blake supported the motion in a personal, independent vote, but the arguments he advanced on Riel in a laborious five-hour speech were dramatically struck down by justice minister John Sparrow David Thompson*.

In encouraging party cohesion and extending the appeal of the Liberals, particularly in the election campaigns of 1882 and 1887, Blake could call upon the traditions, represented by his father and his father’s peers, of reform resistance to special privilege and oppressive rule. He exhorted the Liberal opposition to continue to act as “the special guardians” of “the tone of public morality,” though some of his caucus may have thought his refusal to continue speaking in debates after they had dragged on into Sundays carried the matter too far! These reform traditions helped sustain the intense resistance of Blake and his party in the 1880s to the Conservatives’ continuance of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the gerrymander of electoral boundaries, the electoral franchise act, and the National Policy on tariffs.

Blake launched massive analytical speeches – “desperately long speeches” Cartwright called them – filled in the case of the CPR with objections to careless expenditure, and always referring to the undermining of the nation’s moral fibre through the creation of monopoly. He spoke emphatically on what he saw as the Conservatives’ rejection of representative and responsible government. The intensity of his five-hour attack on the CPR in April 1880 precipitated his take-over of the Liberal leadership, yet in that speech he no longer assailed the principle of western extension, but targeted instead the “airy dreams and vain imaginings” that impelled irrational haste and expenditure. The land grants to the CPR and its monopoly clause were further bases for Blake’s hostility, but in the face of the railway’s important function in suppressing the Riel and aboriginal uprisings of 1885, Blake found the CPR an increasingly fruitless issue.

The bill of 1885 to establish dominion qualifications for voters in federal elections, much like the gerrymander of 1882, brought ferocious resistance by the Liberals. Here was another prime example of the Conservatives’ rejection of representative democracy. The result would be massive illegal padding of electoral lists and consequent improper voting. Blake led his party in a debate, much of it taking place during the major upheavals in the west, that lasted over several months and included a 57-hour filibuster. Though the Liberals managed to remove some of the excesses they saw in the bill, the legislation would distort a generation of Canadian political life.

The exercise of authority over the party proved unsustainable for Blake’s emotional, physical, and intellectual health. He felt understandably unhappy over the Liberals’ failure in the election of June 1882, all the more so because the gerrymander had not clearly contributed to the loss. By the end of the year Blake was prepared to resign as leader but he reconsidered. He thought to leave again in March 1884 under the pressure of illness. The following year, when he sought a rest-cure in Europe, the notion of the inevitability of his resignation was countered only by the Riel crisis; he returned to the idea immediately before the election of 1887 was called.

Blake did no little damage to his party by his repeated talk of resignation, even when it was driven by his neurasthenia and not merely by his sense of personal inadequacy as leader. Cartwright sneeringly described his threats as “escapades” and thought his penultimate resignation would be “regarded as cowardly desertion.” Blake viewed Oliver Mowat as his most obvious replacement and attempted to recruit him just before the election of February 1887. Its call sooner than expected caught Blake short, though it was clear that Mowat was unwilling to take the lead. The inability of the Liberals to gain a majority, despite their improved performance, led Blake to send out a resignation circular to his parliamentary party on 3 March. The outpouring of desperation and support it occasioned, while Blake was on yet another holiday of recovery, in North Carolina, indicated the profound respect with which he was viewed. Always persuadable on issues of duty, he agreed to continue on the condition of an extensive network of help, but his return to the labours of parliamentary leadership brought on his neurasthenia and perhaps other ailments. In this context Blake’s final retirement, on 2 June, was inevitable. Given Mowat’s unavailability, Cartwright’s unsuitability, and the need to bind Quebec to the party, his settling on Laurier as leader is not surprising, though it proved so to both Laurier and the party.

Edward Blake would remain in parliament for two more years, but his presence was not substantial. He first indulged in his usual curative, a European holiday, from the fall of 1887 to the summer of 1888. He then devoted much time to his legal practice. (So complete was his disenchantment with the CPR issue – and such was his love of a fat fee – that in late 1888 he represented the railway in a suit against the federal government over the quality of government-built sections of line.) Since Laurier was viewed by many as an interim leader, Blake’s absence significantly allowed the new chief to establish his credentials. Yet while Blake was away, the tariff issue, driven by Cartwright, was framed to appeal to an Ontarian agrarian community through the advocacy of closer trade relations with the United States.

Unrestricted reciprocity was directly linked to the other great issue of Blake’s time as leader, the National Policy. He had flirted with protectionist ideas through his relationship with Canada First nationalists in the 1870s. His own stance, as it had emerged shortly after he took on the Liberal leadership, was an unexceptional one of incidental protection, closer to the cautious form enunciated by Alexander Mackenzie in the 1870s than to Alexander Tilloch Galt*’s aggressive form in 1858, when incidental protection became a significant public issue. Unlike Cartwright and others who attempted to polarize opinion on a protection-free trade axis, Blake sought to recruit and keep moderate protectionists within the party by arguing that the dominion’s enormous need for revenue could accommodate protection as a secondary aim. He further asserted that pure protectionism would pervert Canadian society by making it politically inegalitarian through unnatural economic advantage and the creation of class distinctions, the absence of which – for Blake – was one of the glories of Canadian life. Given these precepts, Blake could weave together notions of moderate, incidental protection with the lowering of tariffs on necessities, the imposition of taxes on luxuries, and limited reciprocal trade with the United States, as he did in his campaign speech of 22 Jan. 1887 at Malvern (Scarborough), Ont. He was thus able to suppress demands for the party to adopt a radical stance on reciprocal free trade, though the demand emerged full-blown after he left the leadership in 1887.

As Blake made clear in a letter addressed to the electors of Durham West during the election of 1891, which he did not contest, he viewed unrestricted reciprocity as politically subversive, a thoughtless policy that would lead to union with the United States. He was persuaded to keep his explosive letter private during the campaign, probably in the hope that he would let the matter drop. Such a result was unlikely. Blake had too much principle and analytic ferocity: what to most Liberals was an amorphous, comforting slogan that implied better trade relations was to him a precisely definable concept of clear political implication. In the aftermath, Laurier correctly pointed out that Blake had offered no alternative; he left unsaid that Blake’s letter, published in various newspapers after the election, was destructive of party and personal relationships. Blake’s dismay over being attacked in the Liberal press, his shock that other Liberals treated him (in his words) “as if I were dead,” tellingly displayed the limits of his political sensibilities.

The hold Blake had over the Liberal imagination and the immense respect in which his sheer intellectual ability was held nearly overcame his limitations. These factors were evident as Laurier, Mills, Edgar, and others attempted to bring him back into the fold, but they failed to find common ground, while Blake busied himself with legal work and as chancellor of the University of Toronto, a post he held from 1876 to 1900. In June 1892 he received an entirely unexpected invitation to sit in the British House of Commons for the Irish Nationalist party. To Laurier this call may have come as a relief; certainly his pleasure for his friend and former colleague was less lathered with regret than one might expect. For Blake the invitation allowed escape from a nearly intolerable Canadian situation into a field where his reputation was untainted. He accepted, and in July he was elected for Longford South in the centre of Ireland.

Blake’s action precluded a return to active Canadian politics. On three later occasions Laurier, as prime minister, would tempt him with judicial appointments, to the Supreme Court (1896 and 1905) and as chief justice of Ontario (1897), and in 1905 the prime minister would try in vain to secure a seat for him on the JCPC. But Blake could not readily abandon his new cause for the honours of the old. He was bound to an Irish problem that, even after the defeat of Gladstone’s Home Rule Bill in 1893, offered some hope of resolution. For Blake, the challenge was not simple. His model of Irish nationalism, which was set within a federalist, imperial framework, lacked broad appeal in Ireland, and his limited grasp of Irish and British politics prevented much open leadership on his part, a role many had expected. Moreover, his close and early alliance with John Dillon, a major force among the anti-Parnellites, had thrust Blake into the rough factionalism of the Irish party. Still, his political experience was formidable; though dull and long, his major speeches on Home Rule, Irish taxation, and Australian self-government shed “much-needed lustre on the Irish benches”; and he acted as an important mediator, a back-room and occasionally a parliamentary rationalizer of Irish nationalist sentiment. His facilitation included large financial infusions, some personal, others courtesy of his North American connections. And in 1898–1900 he played a significant role in the unification of the nationalist movement.

During the last few years of his Irish involvement Blake’s health deteriorated. In a familiar pattern, he proffered his resignation in the face of divisiveness and when he was attacked directly, but his offers were never taken up. In 1907 his physical decline made his move to resign decisive: a stroke on 24 May left him partially paralysed on his left side. Despite opposition from his Irish colleagues and constituents, he applied for and on 15 August received the stewardship of the Chiltern Hundreds, a legal figment that allowed resignation from the commons. His British parliamentary career at an end, Blake moved to the quiet waters of retirement in Canada.

Blake’s Liberal leadership in Canada and his long involvement with the Irish cause had not precluded the continuation of his highly profitable work as a lawyer. Through a series of partnership adjustments he carefully maintained a place in his Toronto law firm, but this association was effectively ended in consequence of his Irish election. In 1893, under a new arrangement with his firm, he was to be paid only what he earned, a nominal relationship that would be formally ended in May 1901. As well as serving as chancellor for the university, he was chancellor of the Anglican diocese of Toronto from 1883 to 1890. Following his retirement as Liberal leader, he had become increasingly involved, with only marginal participation by his firm, in several high-profile appeals before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Like his ongoing work for the CPR, this involvement contained an ironic element: as minister of justice in 1875 he had favoured the abolition of appeals, but in 1890, to ease references to the JCPC on jurisdictional disputes, he proposed statutory amendments that Sir John Thompson introduced the following year. More casually, in 1900 Blake expressed the great comfort he felt in the JCPC’s dignified but “rather dingy” little room in London. In addition to his appeal work, he took on a number of special political and diplomatic cases, such as the dispute over the Alaska boundary in 1903, an assignment which held the promise of a $30,000 fee but from which he withdrew after five months on account of his neurasthenia. (On some cases he actually worried if he could justify his fee.) Such legal involvement, in and out of parliament, gave him a reputation as one of Canada’s premier constitutional lawyers.

Blake enjoyed particular success in cases that defined dominion and provincial jurisdictions, a concern that he had addressed from his reform perspective as an Ontario mla and as federal attorney general. The challenge continued in a series of legal clashes involving Blake as counsel: the Mercer escheat case of 1881 in the Supreme Court of Canada, St Catharines Milling before the JCPC in 1888, the executive power case of 1891–92 in the Ontario Court of Appeal and then in 1894 in the Supreme Court, and the assignments case of 1893–94 before the JCPC, while Blake was in Britain. Admittedly, the inclinations of the courts and the unimaginative cases made by the dominion often furthered his arguments. Yet, in support of Oliver Mowat’s provincialist crusade, Blake helped furnish the courts with a reasoned alternative to the centralist vision with which Sir John A. Macdonald had attempted to infuse the BNA Act.

Throughout Blake maintained, in his published briefs and in court, that the act had to be interpreted within the “ever widening and deepening current of liberalism.” Moreover, a proper, commonsensical construction could be determined only if all the constitution’s provisions were read together – an approach repeatedly stressed by Blake – in order that “by a broad, liberal and quasi-political interpretation, the true meaning may be gathered.” He was quick to add, however, that convenience or common sense alone was not a suitable vehicle for constitutional interpretation, as he argued on the issue of the lieutenant governor’s executive authority. This understanding was what Blake had gained from his mission to England in 1876: regardless of the theoretical soundness of his case, victory could be founded only on principle framed by common sense.

The essence of these cases was deceptively simple. Based on the tenets of 19th-century Canadian reform liberalism and echoing arguments Blake had made as early as the synod case of 1864, the line that he and Mowat took was that, in creating the Canadian confederation, the provinces had retained their sovereignty and all the necessary aspects of autonomy in order to exercise their jurisdictions within the scope of the BNA Act. Further, any fundamental alteration of that sovereignty or jurisdictional autonomy required the consent of all parties to the original agreement. By emerging victorious in the constitutional battles of the 1880s and 1890s, Blake and Mowat effected a fundamental transformation in the character of Canadian confederation. In this way Blake won victories before the courts that were never allowed him in electoral politics.

Blake held strong family values but, given his busy political and legal careers, he had not always been able to practise them. As a result he felt pangs of guilt, profoundly so after a baby daughter died at home while he and Margaret were en route to England in 1872. His sense of remorse was perhaps reflected in his large gifts of money to his adult children, who did not need, and sometimes objected to, such aid. He could be cool, distant, and harsh with his family, to the point that Margaret, a kindly and intelligent woman, was often silent in his company. She sometimes yearned for more liveliness. Blake was none the less dependent on her for emotional support, which she freely provided. She had given him much needed distance from his parents; her quiet, uncondemning religiosity stood in sharp contrast to his mother’s beliefs. Blake also sought the security of Margaret’s company when buffeted by public life and private doubt. He enjoyed the world away from work with her, at Murray Bay, where a simpler life could be relished, and in his curative and official trips abroad, during which she shepherded him. She had her own moments of subdued public influence. When Blake, in his last days as head of the Liberal party, sought to persuade a reluctant and not broadly supported Wilfrid Laurier that he should take the leadership, Margaret spoke as she nursed her husband: “Yes, Mr. Laurier, you are the only man for it.”

Following his retirement from the British House of Commons in 1907, Blake lived in Toronto on Jarvis Street, near members of his family. Except for occasional holiday absences, he rarely ventured out, and his political contacts withered. He had begun tidying up his estate in 1906, destroying the bulk of his political correspondence; this process continued after his stroke, for he was aware that his time was limited. He died in 1912 at the age of 78. A member of St Paul’s Anglican Church on Bloor Street, he was buried in St James’ Cemetery and was survived by his wife; their daughter, Sophia Hume, wife of Professor George MacKinnon Wrong*; and two sons, Edward William Hume and Samuel Verschoyle, both lawyers.

Edward Blake’s weaknesses – his insecurity, egoism, sensitivity, and gluttony for work – drove his intelligence and achievement. These flaws made him a wretched politician, and the nervous condition that they brought on made his continuous practice of politics difficult; perversely, his acuity and attainment made him a profoundly respected politician. Admittedly he never held the prime ministership. In partisan politics he did not win on issues of trade, finance, or transportation, nor did he generally win on nationalist issues, though his influence in these areas was evident, particularly when he was in government under Mackenzie. The puzzle that Blake represents then is the relative failure of late-19th-century Canadian liberalism in the light of the Liberal party’s subsequent success under Laurier. It is a facile conceit, however, to frame the question of success purely in terms of Blake’s personality and talents: the limitations of his party were rooted in its formation and the ideological and policy outlooks of its leadership over two or three generations.

Moreover, to view Blake strictly as a politician does him injustice. His clearest victories and greatest impact occurred elsewhere: in the shaping of his party and in the imprint of his mind on equity and constitutional law. His political realm was a wide one, in which fundamental precepts had to find expression in social systems and the institutional structures with which those systems were interwoven. The Reform – the Liberal – party was to his mind the carrier of significant social values, whether in power or in opposition. The maintenance and furtherance of these values, in a party increasingly national in scope, was his success. The law too was political: it was imbued with ideology and policy, as Blake believed and as his practice of it showed. During his career he shaped much law, as a premier, as a minister of justice, as a leading figure in parliamentary opposition, and especially as a lawyer in the courts. No wonder that newspaper obituaries reflected on Blake’s Canadian liberalism, his political leadership, and his legal acumen.

[Edward Blake’s personal and political papers are at AO, F 2, and a large portion of the collection is available on microfilm at NA, MG 27, I, D2. Though substantial, they are what was left after his pruning, and his handwriting is none too legible. While in the Department of Justice he generated a voluminous collection of documents and correspondence (NA, RG 13). Recorded in separate departmental letterbooks, his official correspondence helps illuminate aspects of his approach to law and legal questions. Portions are contained in Correspondence, reports of the ministers of justice and orders in council upon the subject of dominion and provincial legislation, 1867–1895, comp. W. E. Hodgins (Ottawa, 1896). Since historian Frank Hawkins Underhill* removed some materials from these collections, his papers (NA, MG 30, D204) must also be consulted. Other sources at the NA that provide significant insight into Blake’s legal and political activities include the papers of Mackenzie (MG 26, B), George Brown (MG 24, B40), Laurier (MG 26, G), and Lord Dufferin (microfilm of originals in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, Belfast, at NA, MG 27, I, B3). David Mills’s correspondence, in his papers at the Univ. of Western Ont. Library, Regional Coll. (London), also contains some material of value.

Many of Blake’s speeches are found in pamphlet form, among them Reform government in the dominion . . . (Toronto, 1878); Edward Blake and Liberal principles, antimonopoly and provincial rights (5v., Toronto, 1878); Hon. Mr. Blake’s speech on the Pacific railway resolutions . . . ([Ottawa, 1884]); and Dominion election: campaign of 1886; Hon. Edward Blake’s speeches (15 nos., Toronto, 1886). Other pamphlets by Blake are listed in CIHM, Reg.

His involvement in a number of noted legal cases and constitutional arguments provides an important entrée into his legal thinking. Some are documented in pamphlet form, though Blake’s authorship is not always acknowledged. His own words demonstrate the strength of his commitment to 19th-century liberalism in concert with his considerable ability to marshal an argument. Important examples include In the matter of the Provincial Synod of Canada . . . (Toronto, 1864); Escheats for want of heirs; the provinces are entitled to them: the argument for the provincial view in the Mercer escheat case . . . (Toronto, 1881); The St. Catharine’s Milling and Lumber Company v. the Queen: argument of Mr. Blake, of counsel for Ontario (Toronto, 1888); The executive power case: the attorney-general of Canada vs. the attorney-general of Ontario (Toronto, 1892); and The Ontario insolvency case . . . (Toronto, 1894).

Blake’s uneven political career would remain baffling if we did not know something of his personal life. J. Daniel Livermore’s analysis of his neurasthenia, in “The personal agonies of Edward Blake,” CHR, 56 (1975): 45–58, has explained much about his otherwise capricious and egotistic withdrawals and resignations. Livermore’s doctoral dissertation, “Towards ‘a union of hearts’: the early career of Edward Blake, 1867–1880” (Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1975), explores personal as well as political and legal themes. Catherine Hume Blake, “Edward Blake: a portrait of his childhood,” ed. M. A. Banks, in Profiler of a province: studies in the history of Ontario . . . (Toronto, 1967), 92–96, can be read as a remarkably revealing document about Blake’s family dynamics and the enormous pressures under which he grew up.

The secondary literature on Blake’s political career is considerable. In his useful two-volume biography, Edward Blake: the man of the other way (1833–1881) (Toronto, 1975) and Edward Blake: leader and exile (1881–1912) (Toronto, 1976), Joseph Schull shows Blake creating a more unified party, but he avoids the difficult, important problems Frank Underhill grappled with in his efforts to make sense of Blake’s role, in what Underhill conceived to be the Liberals’ evolution from a Grit movement to an omnibus party. See Underhill’s Canadian political parties (Ottawa, 1956; [5th printing, with additions, 1974]); In search of Canadian liberalism (Toronto, 1960); “Edward Blake,” in Our living tradition, [first ser.], ed. C. T. Bissell (Toronto, 1957), 3–28; “Edward Blake and Canadian Liberal nationalism, 1867–1878,” in Essays in Canadian history presented to George MacKinnon Wrong for his eightieth birthday, ed. R[alph] Flenley (Toronto, 1939), 132–53; “Edward Blake, the Liberal party, and unrestricted reciprocity,” CHA, Report, 1939: 133–41; “Laurier and Blake, 1882–1891,” CHR, 20 (1939): 392–408; “Political ideas of the Upper Canada Reformers, 1867–78,” CHA, Report, 1942: 104–15; and “Laurier and Blake, 1891–2,” CHR, 24 (1943): 135–55.

Blake’s nationalism and its place in his party is explored in W. R. Graham, “Liberal nationalism in the eighteen-seventies,” CHA, Report, 1946: 101–19, and D. M. L. Farr, The Colonial Office and Canada, 1867–1887 (Toronto, 1959). Underhill made helpful contributions in this area too: in “Edward Blake, the Supreme Court Act, and the appeal to the Privy Council, 1875–6,” CHR, 19 (1938): 245–63; in “Edward Blake’s interview with Lord Cairns on the Supreme Court Act, July 5, 1876,” ed. F. H. Underhill, CHR, 19: 292–94; and in his two “Laurier and Blake” articles.

Brian P. N. Beaven, who generally accepts Underhill’s notion of transition, provides a good ideological and organizational context for Blake after 1880, revealing him as representative of a unifying body of liberal traditions, in “A last hurrah: studies in Liberal party development and ideology in Ontario, 1878–1893” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1982). Also useful is M. A. Western, “Edward Blake as leader of the opposition, 1880–1887” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1939). The changes Blake urged in his Aurora speech – reissued as “Edward Blake’s Aurora speech, 1874,” ed. W. S. Wallace, in CHR, 2 (1921): 249–71 – were thought to be a radical departure from the norms of Reform party policy, though Mackenzie did not think so. On Blake and Canada First, see D. R. Farrell, “The Canada First movement and Canadian political thought,” JCS, 4 (1969), no.4: 16–26; on his relations with Goldwin Smith, see Elisabeth Wallace, Goldwin Smith: Victorian liberal (Toronto, 1957). Margaret A. Ormsby provides a good sense of his role in the British Columbia dispute in “Prime Minister Mackenzie, the Liberal party, and the bargain with British Columbia,” CHR, 26 (1945): 148–73. Blake’s accession is examined in M. A. Banks, “The change in Liberal party leadership, 1887,” CHR, 38 (1957): 109–28. The contentiousness Blake had to face within his party over trade policy is discussed in W. R. Graham, “Sir Richard Cartwright, Wilfrid Laurier, and Liberal party trade policy, 1887,” CHR, 33 (1952): 1–18, and a fine overview of the political tensions surrounding this issue is found in R. C. Brown, Canada’s National Policy, 1883–1900: a study in Canadian-American relations (Princeton, N.J., 1964).

Blake’s career after 1892 has been fully explored by Margaret A. Banks, in Edward Blake, Irish nationalist; a Canadian statesman in Irish politics, 1892–1907 (Toronto, 1957) and “Edward Blake’s relations with Canada during his Irish career, 1892–1907,” CHR, 35 (1954): 22–42. Banks gives clear indication of Blake’s importance as an Irish nationalist, though he was too closely identified with one faction to exercise direct leadership. Also of use for Blake’s Irish career is F. S. L. Lyons, John Dillon: a biography (London, 1968).

On Blake’s legal career the material is limited. Schull’s biography is not particularly penetrating in this sphere and Livermore’s thesis ends in 1880. What the present-day Toronto firm of Blake, Cassels, and Graydon has on Blake is slight, but T. D. Regehr has made good use of its archives in “Élite relationships, partnership arrangements, and nepotism at Blakes, a Toronto law firm, 1858–1942,” in Essays in the history of Canadian law, ed. D. H. Flaherty et al. (7v. to date, [Toronto], 1981– ), vol.7 (Inside the law: Canadian law firms in historical perspective, ed. Carol Wilton, 1996), 207–47. Blake’s heavy involvement in the Court of Chancery can be traced in Grant’s Upper Canada Chancery Reports (Toronto). Jonathan Swainger’s “Governing the law: the Canadian Department of Justice in the early confederation era” (phd thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., 1991) partly addresses Blake’s activities as minister and as architect of the failed attempt to reconstruct the department in 1878. Ian Bushnell, The captive court: a study of the Supreme Court of Canada (Montreal and Kingston, 1992), revises some aspects surrounding the founding of the court but does not reinterpret Blake’s role. In constitutional matters, Christopher Armstrong, The politics of federalism: Ontario’s relations with the federal government, 1867–1942 (Toronto, 1981), is helpful. Paul Romney’s study Mr Attorney: the attorney general for Ontario in court, cabinet and legislature, 1791–1899 (Toronto, 1986) and his DCB entry on Sir Oliver Mowat emphasize the Ontario premier in his fight for provincial rights, with Blake as the junior colleague. At times, Blake’s own view of his performance was quite the opposite. b.f. and j.s.]

Cite This Article

Ben Forster and Jonathan Swainger, “BLAKE, EDWARD (baptized Dominick Edward),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blake_edward_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blake_edward_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ben Forster and Jonathan Swainger |

| Title of Article: | BLAKE, EDWARD (baptized Dominick Edward) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 22, 2025 |