Source: Link

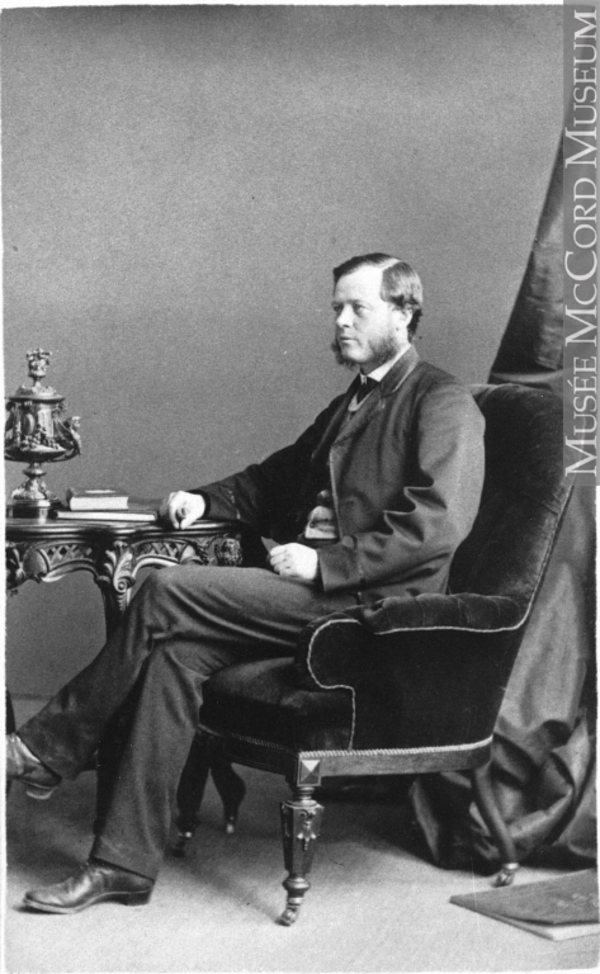

MOSS, THOMAS, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 20 Aug. 1836 in Cobourg, Upper Canada, eldest of the four children of John Moss and Ann Quigley; m. 28 July 1863 Amy (d. 1880), eldest daughter of Robert Baldwin Sullivan*, and they had two daughters and six sons (two sons died in infancy); d. 4 Jan. 1881 in Nice, France.

Soon after the birth of Thomas Moss, his family moved to Toronto where his father acquired and operated a brewery. Thomas was educated at Gale’s Institute and then at Upper Canada College from 1850 to 1854 where in his final year he was head boy and won the governor general’s prize. He continued his education at the University of Toronto, receiving its first scholarships in mathematics and classics and becoming prominent in the Literary and Debating Society before graduating in 1858 with a ba and three gold medals. In 1859 he received an ma and wrote the prize-winning thesis for that year. Moss maintained his connection with the university by filling the posts of registrar from 1861 to 1873, senator, and, from 1874 to his death, vice-chancellor. During these two decades when the university was suffering difficulties, Moss was one of its staunchest defenders. After his death the university named a building and established two scholarships in classics in his honour.

Moss began the study of law in 1858 in the Toronto office of Adam Crooks and Hector Cameron and was called to the bar in 1861. He practised law first with Cameron, then with James Patton and Featherston Osler. In 1871 he formed a successful partnership with his brother Charles*, later chief justice of Ontario, William Alexander Foster, a leader of the Canada First movement, and Osler; Robert Alexander Harrison* joined the firm in the following year. In 1871 Moss was appointed equity lecturer for the Law Society of Upper Canada and elected a bencher. When he was its chairman, the law society’s committee on legal education prepared a report which led to the establishment of a law school in 1873. In 1872 he was appointed a member of the Law Reform Commission, and was named a qc. That same year he was offered the vice-chancellorship in the Court of Chancery by Sir John A. Macdonald*’s government but he declined because the salary was insufficient for the needs of a large family and his own style of living. Still in his mid 30s, Moss was now well established in his profession and was a member of the Toronto, National, and Rideau clubs. Although he had been a Roman Catholic, by the time of his marriage he had become a member of the Church of England and supported the low church group.

In 1873 Moss turned briefly to a new career. In December he allowed his name to be put forward as a Liberal candidate in a federal by-election in Toronto West. With support from members of the Toronto Trades Assembly and the Canada First movement, and with the Pacific Scandal in the air, Moss won election in the normally Conservative constituency. The victory provided the new government of Alexander Mackenzie* with an important impetus and confidence which it carried into the federal general election in January 1874. Re-elected, Moss was chosen, as one of the promising young Liberals, to move the address in reply to the speech from the throne. He was not, however, particularly active in parliament and only introduced two minor bills. He assisted the government in drawing up the new Insolvent Act of 1874 and spoke twice in favour of the Supreme Court Bill of 1875.

As a lawyer, Moss had had professional contact with and admiration for Edward Blake*; the two men were close friends and seat-mates in the House of Commons. Both supported some of the ideas of the Canada First movement, and although neither man belonged to it, they were willing to use it to their own political ends. Moss was therefore identified with the Blake wing of the Liberal party and, like Blake, opposed George Brown*’s dominance in the Ontario Liberal party. In January 1875 Moss joined in founding the Toronto Liberal as a “more progressive” Liberal organ than George Brown’s Globe.

Moss nevertheless retained the respect and confidence of both Mackenzie and Brown, and was thus able to play an important role in the spring of 1875 when, as Blake’s representative, he participated in the negotiations that led to Blake’s return to the federal cabinet in the justice portfolio. In 1875 he was active in the provincial election campaign. That fall, however, he was offered a judgeship on the Court of Error and Appeal for Ontario. He was suffering from financial difficulties, his heavy investments in the Liberal having been lost when the newspaper failed in July 1875, and the judgeship would give him a large, constant income. After he was assured by Blake that his departure would not hurt his friend’s position in the ongoing power struggle in the Liberal party, he accepted and was commissioned on 8 Oct. 1875. He was appointed chief justice of the Court of Appeal on 30 Nov. 1877 and a year later, at the age of 41, became chief justice of Ontario.

As a judge, Moss was known for the easy, graceful manner with which he conducted cases and for the untiring energy and thought which went into his judgements. He rarely wrote dissenting opinions, but he seemed to enjoy writing separate, often lengthy, concurring judgements. Moss rendered a number of important decisions, several being remarkable for their protection of the rights of individuals against the arbitrary use of power by governments or large corporations. In Yeomans v. the Corporation of the County of Wellington (1879), Moss, noting “that individual property rights shall not be sacrificed for the general good, and that the citizen shall not be required to relinquish his private property to the state without receiving a fair equivalent,” found that an individual property owner was entitled to compensation because a county road had been constructed so as to injure his property. In Fitzgerald et al. v. the Grand Trunk Railway Company (1880) he denied that a large corporation could free itself from liability for negligence by the inclusion of a clause in contracts denying that it had any responsibility. This particularly influential decision was upheld in the Supreme Court of Canada and was relied upon in later cases.

In 1880 Moss was forced to cease attending the court because of ill health and was ordered to a warmer climate. He left with some of his family for the south of France but during the ocean voyage caught a severe cold from which he was unable to recover.

AO, MU 159–62. Canada Law Journal, new ser., 17 (1881): 55–60. Reports of cases decided in the Court of Appeal [of Ontario] . . . , comp. J. S. Tupper et al. (27v., Toronto, 1878–1901), I–V. Globe, 1863, 1873–74, 6 Jan. 1881. Leader, 1873. Toronto Daily Mail, 6–7 Jan. 1881. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, I: 353–55. Read, Lives of judges, 387–403. N. F. Davin, The Irishman in Canada (London and Toronto, 1877), 608–9. D. W. Swainson, “Personnel of politics,” 255–59. D. P. Gagan, “The relevance of ‘Canada First,’” Journal of Canadian Studies, 5 (1970), no.4: 36–44. J. [G.] Snell, “The West Toronto by-election of 1873 and Thomas Moss,” OH, 58 (1966): 236–56.

Cite This Article

J. G. Snell, “MOSS, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moss_thomas_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moss_thomas_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. G. Snell |

| Title of Article: | MOSS, THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |