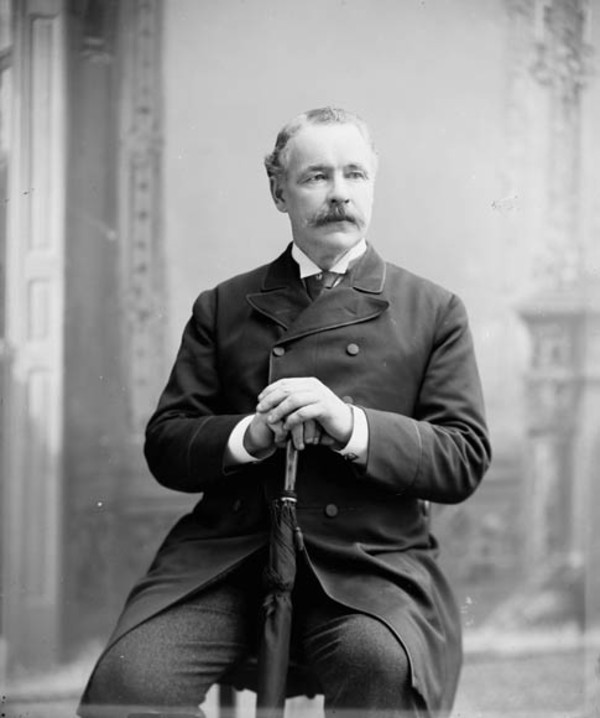

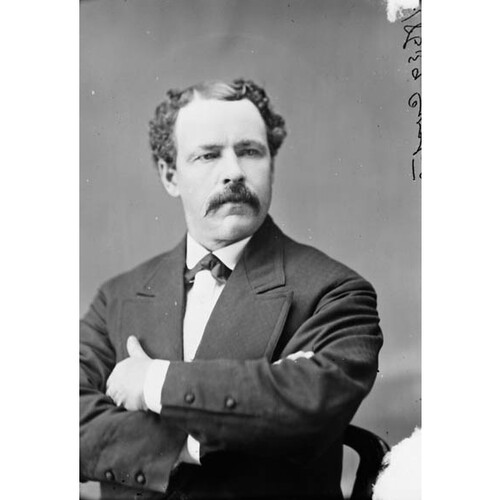

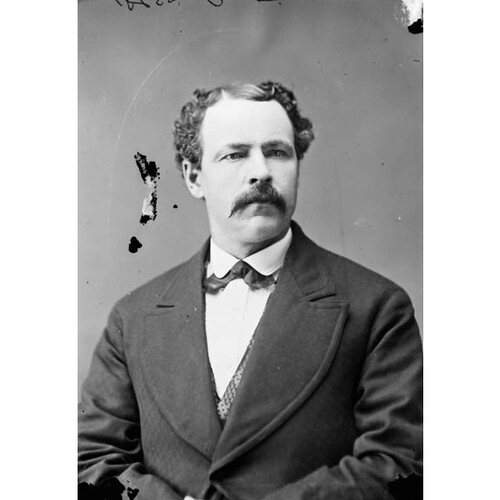

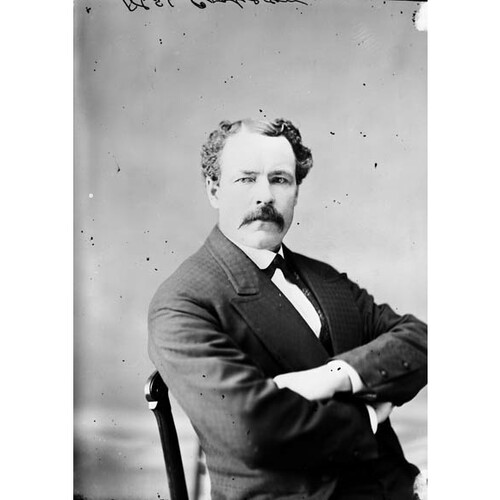

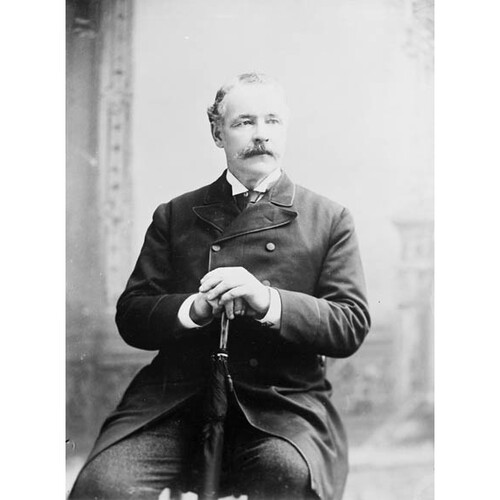

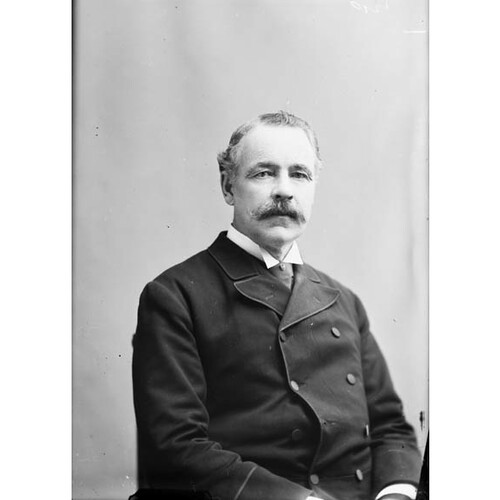

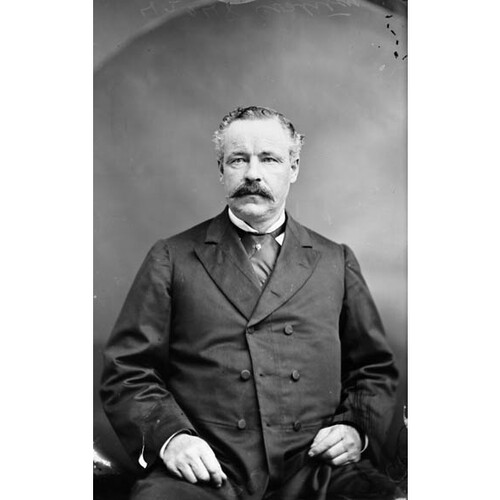

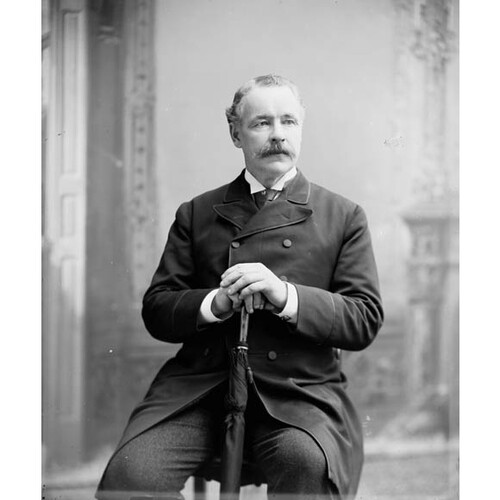

COSTIGAN, JOHN, politician; b. 1 Feb. 1835 in Saint-Nicolas, Lower Canada, son of John Costigan and Bridget Dunn; m. 23 April 1855 Harriet S. Ryan (d. 1922) in Grand Falls, N.B., and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 29 Sept. 1916 in Ottawa and was buried in Grand Falls.

John Costigan’s father, a native of Kilkenny (Republic of Ireland), emigrated to Lower Canada with his wife in 1830 and settled in Saint-Nicolas, where he worked as agent for Sir John Caldwell*. Ten years later he moved to Grand Falls, to manage Sir John’s mills there. John was educated locally and from 1850 to 1852 at the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière in Lower Canada. After returning to Grand Falls he became registrar of deeds and wills for Victoria County (1857) and a judge of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas, but he resigned these posts in 1861, when he was elected to the House of Assembly for Victoria as a conservative. He was soon caught up in the dramatic events surrounding confederation, which he opposed. An election was called on the issue for February–March 1865, and it resulted in a major defeat of the confederate forces under Samuel Leonard Tilley*. Costigan’s victory was short-lived, however, for the imperial government in London instructed Lieutenant Governor Arthur Hamilton Gordon to effect a reversal of the electoral result.

The new government of Albert James Smith* was a loose alliance of parties with no homogeneous identity and no policy aside from antagonism to the Quebec resolutions. It included the conservative Costigan and the liberal Timothy Warren Anglin*, who were beginning a long rivalry for leadership of the Irish Catholic community. Exploiting the differences within the coalition, the lieutenant governor forced the resignation of the government in April 1866, precipitating another election on the confederation question. Before the inhabitants of New Brunswick could express their views, members of an Irish American organization, the Fenian Brotherhood, arrived on the border, announcing that they had come to save the colony from union. This intervention provoked a natural reaction among the people, who promptly voted in favour of the new nation. Both Costigan and Anglin were labelled fellow-travellers of the Fenians, and both lost their seats.

Like so many others who had opposed confederation, Costigan decided to transfer his political attention to the wider field of federal affairs. He won the seat for Victoria in the House of Commons in 1867. Sitting as a Conservative, he set his sights on becoming the recognized representative of Irish Catholics in the new dominion, particularly after the acknowledged holder of that title, Thomas D’Arcy McGee*, was assassinated in 1868. Costigan began to cultivate his relations with the Catholic bishops of New Brunswick, John Sweeny* and James Rogers*, with whom his rival Anglin had fought during the confederation debates. The New Brunswick Common Schools Act of 1871 was to provide him with the opportunity to establish his credentials as defender of Catholic rights in his province.

This act, which came into effect on 1 Jan. 1872, provided that all schools in the province were to be non-sectarian. The bill, an initiative of the government of George Edwin King*, had been opposed by the Catholic hierarchy, and attempts had been made to allow for a separate Catholic school system. These efforts having been unsuccessful, the bishops turned to their representatives in Ottawa for support in getting the act disallowed. The issue brought Costigan and Anglin together again, although the latter’s place as a member of the Liberal opposition left him at a disadvantage. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* proved unsympathetic to approaches by the bishops orchestrated by Anglin. Costigan, however, was a government supporter, in a position to influence Macdonald and his ministers – or at least to embarrass them. On 20 May 1872 Costigan rose in the commons to move that the schools act be disallowed. This motion, which attracted considerable support, placed Macdonald in a dilemma. He was almost certainly personally opposed to disallowance, and the Orange element, always strong in the Conservative party, would strenuously object to a separate school system in New Brunswick. Costigan was thus approached by an envoy from Macdonald who suggested a compromise, introduced as an amendment by Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, under which the Catholics of New Brunswick would be given guarantees that their unofficial separate schools would be preserved, without the need to disallow the schools act. At first, Costigan was prepared to go along with this compromise, as were a number of Liberals, but even it was beyond the government. Another amendment was introduced regretting the position in which New Brunswick Catholics found themselves, and merely hoping that something would be done by the provincial government to ameliorate the situation. This completely insipid resolution was passed, and Costigan was outraged. In a final attempt to avoid responsibility, the house agreed that the opinion of the law officers in London would be sought before any further action was taken.

Costigan’s resolution was a brave move. He wanted to represent the Irish Catholics of New Brunswick in Ottawa, but he was also a Conservative politician. Not many who opposed Macdonald so openly could hope to advance to positions of influence in the party. The advantage he did gain, however, was the support of the New Brunswick bishops, against Anglin and other aspirants to the office of spokesman for the Irish Catholic community.

Although the law officers would rule the schools act to be constitutional, there was further legislation for Costigan to oppose. In 1873 the provincial assembly passed a number of measures regarding assessment of taxes for schools, which effectively forced Catholics to pay for a system they found objectionable. Anglin did not believe that a motion for disallowance could be successful, but Bishop Sweeny prevailed on Costigan to introduce such a resolution in the commons on 14 May 1873. This time, Costigan succeeded, in spite of the open opposition of Macdonald and many Conservatives. However, rather than pass the resolution on to Governor General Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*], Macdonald simply requested him to apply to the Colonial Office for instructions.

Costigan attempted to continue the pressure on the house to deal with the schools issue, even after the Colonial Office had upheld the validity of the assessment acts. Having been persuaded by Bishop Sweeny to find another approach, on 8 March 1875 he moved yet another resolution in the commons, this time asking that the queen be petitioned for an amendment to the British North America Act which would grant to the Catholics of New Brunswick the educational privileges enjoyed by minorities in Ontario and Quebec. At this point the Conservatives were out of office, and it was the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie* that opposed his resolution. It was defeated, and an attempt by him to have an amendment passed was ruled out of order by Anglin, now speaker of the house.

The schools issue was ultimately settled through negotiations in New Brunswick [see John Sweeny]. But Costigan had proved himself to be a loyal and willing representative of the Irish Catholics of that province. For his pains, he received the complete support of the bishops in the 1874 election. When the Conservatives returned to power in 1878, Bishop Rogers lobbied for a cabinet position for Costigan, but Macdonald had not forgotten the 1872 resolutions and the embarrassment they had caused him. Costigan remained on the back benches.

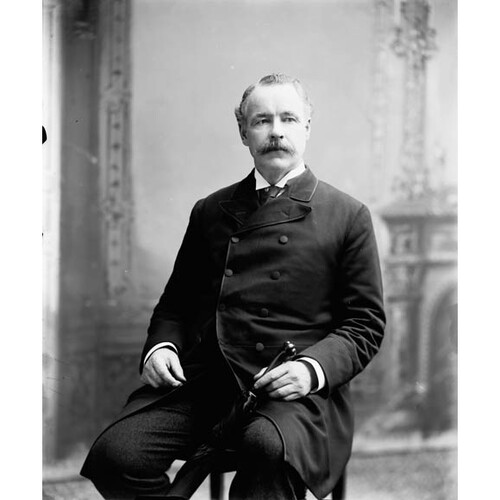

Having failed once again in 1880 to be appointed to the cabinet, Costigan was offered an opportunity in 1882 to achieve his main political ambition: to become the representative of Irish Catholics in the dominion. In February he was asked by John Lawrence Power O’Hanly, an active Irish Canadian nationalist, to move a resolution in the commons in favour of Home Rule for Ireland. At this time Home Rule dominated British politics, and O’Hanly believed such a motion would be of use to the Irish Nationalists at Westminster, under the leadership of Charles Stewart Parnell. O’Hanly hoped too that, through the support of all Irish Canadians, Costigan could rise above party politics and attain the status of a Canadian Parnell. After meeting with leading Irish Catholics in Ottawa, Costigan prepared to introduce strongly worded resolutions in the House of Commons on 18 April 1882. The clauses called unequivocally for Home Rule for Ireland and the release of Parnell and his lieutenants from prison, where they had been lodged by William Ewart Gladstone’s government for advocating rent strikes in Ireland. On the day before the resolutions were to be introduced, in a move which recalled his action at the time of the New Brunswick schools issue, Macdonald persuaded Costigan to accept compromise resolutions which, in the view of the Liberal leader, Edward Blake, “emasculated” the original ones, and which Macdonald himself termed “perfectly harmless.”

Although the compromise resolutions were carried in the house and Senate, and were to prove the strongest resolutions ever passed by a Canadian parliament on the Home Rule question, they were a major disappointment to O’Hanly and his friends. The man they hoped to make the Parnell of Canada, “in a position independent of parties and governments,” had chosen instead to give priority to his party political career. The fact was that Costigan’s original resolutions had come as a great shock to Macdonald, who had just called an election for the summer of 1882. He did not wish to alienate his Orange supporters in the key province of Ontario, nor was he eager to upset the powerful Irish Catholic population. On a more personal level, Macdonald did not believe in Home Rule for the Irish, whom he considered incapable of self-government. Furthermore he feared that support for it would only encourage those already pushing for greater powers for the Canadian provinces to the detriment of the federal administration. Costigan agreed to turn his back on O’Hanly and his group in return for finally achieving a great ambition: a seat in the federal cabinet. The Costigan resolutions were passed by the House of Commons on 21 April 1882. On 23 May, it was announced that John Costigan had been appointed minister of inland revenue. That same day Bishop Rogers wrote to him to assure him of the Catholic hierarchy’s support for the Macdonald government, due to face the electorate the following month.

Having become the Irish Catholic representative in the federal cabinet, where he was soon joined by fellow Irish Catholic Frank Smith* of Ontario, Costigan abandoned Home Rule, refusing to support attempts to pass further resolutions in the commons though he still favoured the concept. He became Macdonald’s messenger to troublesome Irish Catholics in the dominion, most especially immediately before and during election campaigns. His role was to deliver the Irish Catholic vote and deal with attempts by the Liberal party to woo it away. He was not the success he had hoped to be in his chosen role, however. As the century progressed, Edward Blake came more and more to be acknowledged as the spokesman for the Irish, particularly in relation to Irish national affairs. Moreover, Costigan soon realized that Macdonald was not going to be quick to favour the Irish in the matter of patronage appointments, despite Costigan’s place in cabinet. In fact, he felt constrained to resign from his ministry in 1884 because he believed the prime minister had shown himself unsympathetic to the advancement of Irish Catholics. In addition, he saw that Orange influence in the cabinet was far greater than anything he could command.

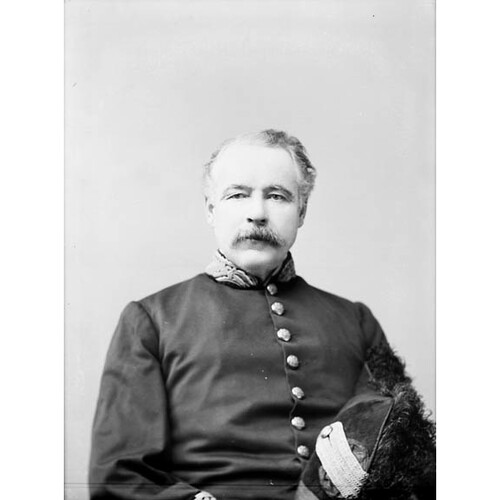

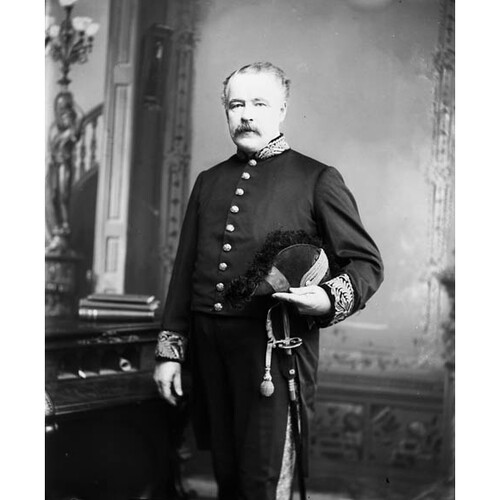

Although Macdonald considered Costigan to be ineffective and unreliable, he needed the Irish Catholic vote, particularly in the Atlantic region. Costigan’s resignation was therefore not accepted. Nor did Costigan press it. There is evidence, however, that he attempted to resign once more, in 1887, but again Macdonald dissuaded him. Between 1882 and 1892, under Macdonald and then John Joseph Caldwell Abbott*, he held the position of minister of inland revenue. After the Abbott ministry was abolished, he served as secretary of state under Sir John David Sparrow Thompson* until 1894, when he was appointed minister of marine and fisheries by Mackenzie Bowell. In 1885 Costigan had been presented with the title to a house in Ottawa by his supporters, a common enough expression of satisfaction with the work of a leading politician. Yet his later years in office were not altogether happy. He strongly disliked the influence and attitude of Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper*, and refused to take part in what he saw as the political assassination of Bowell by Tupper and extreme Orangemen such as Nathaniel Clarke Wallace*. He nevertheless retained his portfolio when Sir Charles Tupper succeeded Bowell in April 1896. In the election that year he held on to his seat, but the Liberal victory turned him out of office. His relations with leading Tories continued to deteriorate until, in 1899, he formally announced that he was leaving the Conservative party and would sit as an independent. His attitude was that the party had rather left him, since it had moved away from the inclusive, nation-building policies of Macdonald. In 1907 he was appointed to the Senate on the advice of the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

A federal politician of Costigan’s standing played a major role in the social and cultural life of those he represented, and Costigan was involved in many Irish organizations, including the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the United Irish League, of which he was the Ottawa president. This involvement culminated in his being sent as a delegate to the Irish Race Convention, held in Dublin in 1896. In 1895 Costigan had joined with another Irish Canadian leader, Nicholas Flood Davin*, in seeking to have the federal franchise extended to women in Canada. Although he was able to use his political status to promote various mining and oil companies, Costigan never achieved the stature in Canadian politics that O’Hanly had wished for him. In 1882 he had had visions of himself as a Canadian Parnell, but the lure of office was too strong. Eclipsed by Blake in his desire to be the undisputed leader of the Irish in Canada, he settled instead for being a loyal minister in John A. Macdonald’s cabinet, recognizing that he could do little to advance Irish Catholic interests in a cabinet that was powerfully influenced by the Orange order. Years of official status took the place of real influence and leadership. Irish Catholics failed to find a Parnell, and Costigan failed to realize his dream of leading a solid, independent voting bloc in the Canadian federation. He died in Ottawa on 29 Sept. 1916, aged 81.

ANQ-Q, CE1-21, 2 févr. 1835. AO, F 2 (mfm. at NA). NA, MG 26, A; G; MG 27, I, D5; E12; MG 29, B11. PANB, MC 1156. Saint John Globe, 30 Sept., 3 Oct. 1916. W. M. Baker, “Squelching the disloyal, Fenian-sympathizing brood: T. W. Anglin and confederation in New Brunswick, 1865–6,” CHR, 55 (1974): 141–58; Timothy Warren Anglin, 1822–96: Irish Catholic Canadian (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1977). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1867–1906. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). N. F. Davin, The Irishman in Canada (London and Toronto, 1877; repr. Shannon, Republic of Ire., 1969). L. J. Hynes, The Catholic Irish in New Brunswick, 1783–1900, ed. J. E. Belliveau ([Moncton], n.d.). W. S. MacNutt, New Brunswick, a history: 1784–1867 (Toronto, 1963; repr. 1984). David Shanahan, “Irish Catholic journalists and the new nationality in Canada, 1858–1870”

Cite This Article

David Shanahan, “COSTIGAN, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 25, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/costigan_john_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/costigan_john_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Shanahan |

| Title of Article: | COSTIGAN, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 25, 2026 |