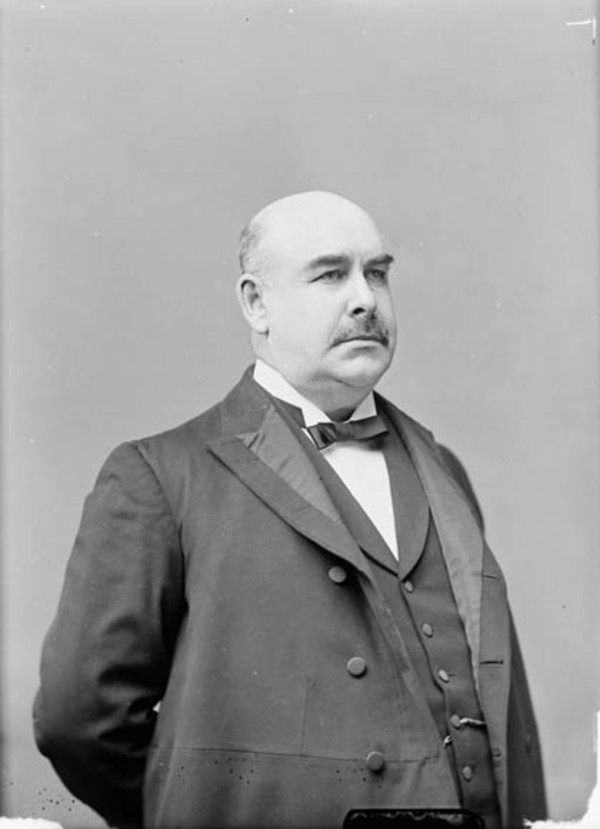

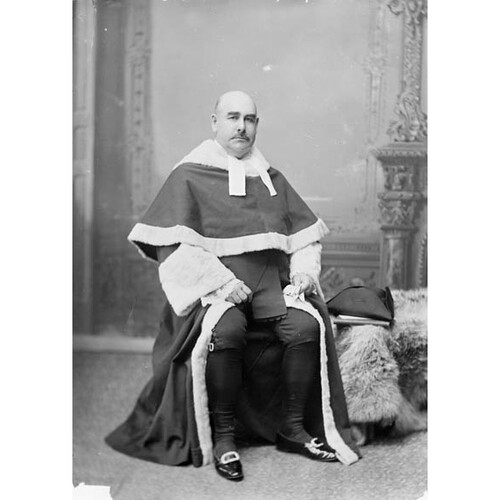

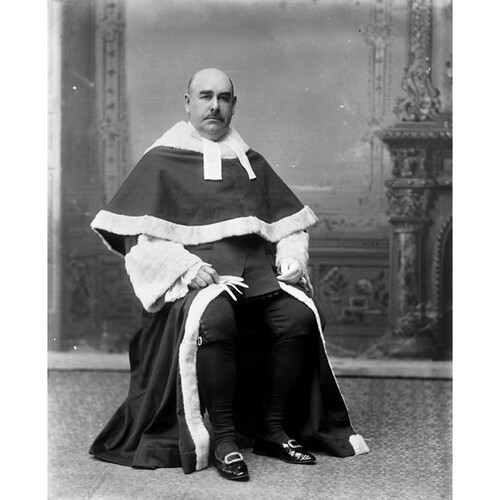

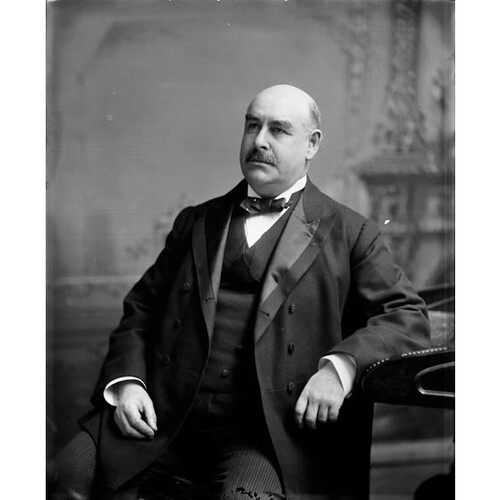

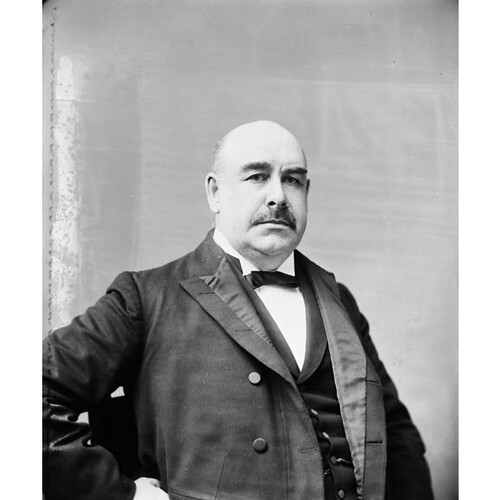

KING, GEORGE EDWIN, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 8 Oct. 1839 in Saint John, N.B., son of George King* and Mary Ann Fowler; m. 28 Nov. 1866 Lydia Eaton, and they had a son and a daughter; d. 7 May 1901 in Ottawa.

George E. King was born into a prosperous family of Saint John shipbuilders, his father one of those successful tradesmen who experienced a rapid social advance as a result of the expansion of the New Brunswick shipbuilding industry in the mid 19th century. The Kings were prominent members of the city’s burgeoning Wesleyan Methodist community. Young George was sent to Mount Allison Wesleyan Academy at Sackville and then to Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn. (ba 1859, ma 1862). He was articled to Robert Leonard Hazen* in Saint John, made an attorney in 1863, and called to the bar in 1865. He set up practice in his native city.

In October 1867 King was returned to the New Brunswick House of Assembly at a by-election in Saint John County and City. His political affiliation has been viewed as confusing: he usually identified himself as a Liberal (or a Liberal-Unionist), but he often supported Samuel Leonard Tilley*, a federal Conservative, and Tilley’s organization in New Brunswick and he would run on behalf of the Tories in the federal election of 1878. This seeming inconsistency reflects the divisive effect of the intrusion of Canadian issues into New Brunswick politics. The Reform coalition headed by Charles Fisher* and Tilly which had governed the province between 1857 and 1865 had split over the issue of union with Canada, and most Liberals, including King, had followed Tilley in support of it. Since under confederation the province was dependent on the central government for nearly 90 per cent of its revenues, the traditional political network based on Tilley, who had entered Sir John A. Macdonald*’s Conservative government in 1867, was vital, the more so since he was the cabinet minister responsible for New Brunswick. Despite the close connection between the provincial Liberals and the federal Tories, King seems always to have regarded himself as a Liberal.

New Brunswick provincial politics after 1867 continued to centre on confederation. The government of Andrew Rainsford Wetmore* was a coalition of Liberals and Tories who supported the union but who often had little else in common. Hence the Executive Council between 1867 and 1870 was characterized by extreme instability. Among those brought in was King, who at the age of 29 was made a member without portfolio on 2 March 1869. A man of broad intelligence, highly organized, with a powerful will and a commanding public presence, he rapidly became a leader in the administration, increasingly setting its agenda and steering its policies through the legislature. His concerns, reflecting his liberal and Methodist values, at first focused on issues of civil liberty and social improvement. He argued for something approximating universal manhood suffrage on the grounds that individual rights were higher than mere property rights. On the same principle he was prepared to promote universal female suffrage, advocated removal of all property qualifications for election to the legislature, and supported the right of women to be elected. Similar attitudes were reflected in his views on the imprisonment of debtors, a punishment he saw as pressing largely, and unfairly, on the poor.

King’s first major bill (1869), which he wrote and personally saw through the legislative process, pioneered the judicial review of electoral proceedings in Canada. In the same year he supported an act which extended married women’s rights to control any property and income they legally owned. Finally, in a new debtors’ bill, which passed in 1870 over great opposition, he proposed that after a year in prison debtors would be freed and never again prosecuted for the same debt. Although he objected to the severity of this bill, he acknowledged that politically he could do no more and, in fact, the bill was amended in committee to extend the period of imprisonment to two years. In 1874, however, his government would abolish imprisonment for debt. King did not introduce legislation to extend the franchise to women. His experience with the debtors’ issue made clear the obstacles that faced major reform, and his majority in the assembly before 1874 was always tenuous. More important, his considerable energies were largely consumed after 1870 in the struggle for the public school system.

Almost from the time of his arrival in the legislature King’s priority was the creation of a universal, publicly supported elementary school system. There is no question that he was the principal architect of the Common Schools Act of 1871. Less clear are the other influences at work. Lieutenant Governor Lemuel Allan Wilmot*, a leading reformer of earlier years, a prominent Methodist, and a passionate advocate of a single, tax-supported public school system, doubtless had an effect on the government’s program, as did Egerton Ryerson*, superintendent of education for Ontario, whose ideas were familiar to King. So also did the New England educational experience, with its assumptions about church and state, which King had known a decade earlier, and the Nova Scotia schools experiment initiated by Charles Tupper*’s Free School Act of 1864. Then, too, King was a child of the 1860s, years that had witnessed Pope Pius IX’s declaration of the Syllabus of Errors and the early European debates over schools and the role of the state in their formation.

The framework of the new school system was worked out between 1868 and 1870. The bill which King presented to the 1870 sitting of the assembly was based on eight interrelated principles: schools should be free to all children; there should be efficient central control of the system and effective supervision of every teacher; provincial financial aid should be made available but local support must be secured by law; the school system should be as simple as possible; and there must be freedom of conscience. Support would be provided in part by provincial grants, in part by a general county assessment, and in part by local assessment.

It became obvious after weeks of consideration that the bill would not pass. The schools issue cut deeply across the rudimentary coalition governing the province, and supporters and opponents of the measure were found on both sides of the house. Among opponents, some saw the bill as too radical, particularly in providing for compulsory assessment, others as not radical enough, since it permitted grants to denominational schools to continue. The Wetmore government dared not risk its dwindling credibility in a vain effort to force through a major social program in the face of an election, scheduled for the summer. In despair, King withdrew the bill. Wetmore then sought and received a federal appointment to the bench. On 9 June 1870 King assumed the mantle of premier and was sworn in as attorney general. He was 30 years old, the youngest person to hold the leadership in the history of New Brunswick.

The office was no prize. Opposition to Wetmore’s coalition had grown steadily since 1868 and, because King was young and inexperienced, his incumbency was expected to be short. None the less he mounted a credible campaign, based on the need for the schools act and for “better terms” for New Brunswick within confederation. The results were essentially a draw. Although the government had lost support, it seemed able to command the allegiance of about half of the newly elected assemblymen. As a result of vigorous action on the part of opposition leaders, however, by the time of the first session 23 of the 41 members had committed themselves to vote no-confidence in the government.

In the speech from the throne on 16 Feb. 1871 Wilmot announced that the government’s principal order of business would be the passage of a new schools act. On the third day of the session King and his government resigned. At this point the proceedings grow murky. Somebody – probably Wilmot – began negotiations between King and George Luther Hatheway*, one of the opposition leaders and a committed public school supporter. Wilmot offered the premiership to Hatheway and he agreed to form a government. On 22 February the new Executive Council was sworn. Hatheway became provincial secretary, King remained attorney general, and the rest of the administration consisted of a mixture of King and Hatheway supporters. The new government was united on one issue: the common schools.

On 12 April King again introduced the schools bill to the house. The debate was long and sometimes bitter, uniting against the measure most Catholics, some Anglicans, and all those opposed to compulsory assessment. On 5 May, at the behest of many free school supporters, a provision was added that schools under the act should be non-sectarian. It carried on a 25–10 vote. At King’s insistence control of the school system was placed in the hands of the Executive Council, which together with the superintendent of education (the first would be Theodore Harding Rand*) and the president of the University of New Brunswick (William Brydone Jack*) was to form the new Board of Education. The board would draw up the regulations prescribing the curriculum and the textbooks, defining the qualifications of teachers and the terms under which they must work, and setting the way in which local schools were to be conducted. Passed into law on 17 May, the act came into effect on 1 Jan. 1872, and dealing with its consequences would be a principal preoccupation of the government over the next three years.

The schools act quickly became a cause célèbre in the federal arena. New Brunswick Catholics appealed to Ottawa to disallow it on the grounds that Catholic schools had existed under the Parish Schools Act of 1858 [see John Sweeny] and Catholics thus had constitutional rights to sectarian schools under the British North America Act. No member of the federal cabinet was prepared to support such a proposition. In the spring of 1872 the issue was raised in the House of Commons by two New Brunswick Catholic members, John Costigan* and Timothy Warren Anglin*. A motion to force the government to disallow the schools act was presented by Costigan, and a proposal asking the queen to amend the British North America Act to protect the sectarian schools of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia was brought forward by Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, a Quebec mp and the premier of that province. In the end the commons defeated both proposals and contented itself with resolutions asking the New Brunswick government to reconsider its position and seeking the opinion of the law officers of the crown in London on the constitutionality of the act.

The responsibility for responding to the attack on the schools act fell to King. After Hatheway’s death on 5 July he once again assumed the leadership of the government, with John James Fraser* as his provincial secretary. Five months later, in reply to the parliamentary resolution asking that the province reconsider its position, King drafted a 12-page memorandum in which he countered the argument that legal Catholic public schools had existed at the time of confederation. “Privileges enjoyed in violation of the law,” he maintained, “cannot give rights under the law.” He struck back at other points as well. When the constitutionality of the schools act was challenged in the Supreme Court of New Brunswick, he won the appeal early in 1873. Since the court on a number of occasions found the assessment clauses of the act to be defective, King introduced a series of assessment acts and made the assessments retroactive.

It was a costly victory. Part of the price was the friction and social dislocation resulting from the new policy. Other costs were more tangible. By 1872 the province was in financial difficulties, and the need for better terms from Ottawa was acute. Nearly two years of disappointment passed before the problem was worked out in favour of the province by King and Tilley, now federal minister of finance. In 1873 the dominion subsidy to New Brunswick negotiated at the time of confederation was increased. The province was also given an annual grant of $150,000 in compensation for surrendering, under the Treaty of Washington (1871), its export duties on American goods using the Saint John River. The grant alone represented a 30 per cent increase in the provincial revenue and the export duties were soon replaced with stumpage fees. These new funds enabled the King government to promote social and economic development.

The inability of New Brunswick to attract immigrants had long been a matter of concern. In 1872 the Executive Council had begun a campaign to recruit suitable agricultural migrants in the United Kingdom. King drew up regulations providing that every family could, on certain conditions, acquire up to 200 acres of crown land and assuring them of some support until they had completed their homesteads. In the main these privileges were extended to group settlements in designated areas of the province.

The railway policy of the King government was a continuation of two earlier policies. In 1870, angry at the decision of Sandford Fleming*, chief engineer of the Intercolonial Railway, to run the line along the thinly populated back country which was then the North Shore of the province, the Wetmore government offered land grants of 10,000 acres a mile to any promoter willing to construct a competing railway up the more populous Saint John River valley from Fredericton to Edmundston. The proposal was taken up by a consortium, including Alexander Gibson*, which incorporated the New Brunswick Railway Company. Between 1872 and 1875 the Executive Council granted the company 1,115,000 acres of crown land, about six per cent of the land mass of the province. As well, the older development policy of cash grants was continued. The railway subsidy acts of 1873 and 1874 – implemented around the time that better terms were negotiated with Ottawa – revived the practice of providing $5,000 a mile for approved private construction. Seven railways were built under this legislation during King’s tenure of office and subsidies of more than $625,000 were authorized.

In the spring of 1873 King’s attention was brought back to the schools issue. Having failed in their efforts to abort the act – the cabinet, the courts, and the law officers of the crown agreed that the province had acted legally – the Catholic bishops of Saint John and Chatham, John Sweeny and James Rogers, turned to Costigan and the Quebec hierarchy in an effort to press the New Brunswick government to alter its policy. Although the Quebec hierarchy would not move too far against Macdonald and the federal Conservative government, Costigan made an effective appeal to the commons asking that the governor general disallow the New Brunswick acts which permitted assessment for local schools. The motion passed. Macdonald refused to disallow the legislation, but as an act of conciliation requested parliament to provide $5,000 in support of an appeal by the New Brunswick Catholics to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, the highest court in the British empire.

This second federal intervention stirred the fires of religious rancour within New Brunswick. By mid 1873 court-ordered seizures of the property of leading Catholics who refused to pay their school taxes were occurring in Saint John. At King’s initiative meetings were held with Sweeny in an effort to achieve a compromise. The bishop offered peace under a number of conditions, but the Executive Council was unable to agree to some of them. The accelerating debate reached a climax in the 1874 session of the assembly. The debate was the most bitter of the period and suggests that moderate reformers such as King, who had had to be pushed into supporting the non-sectarian clause in order to get the schools act through the legislature, were now committed to a policy of no compromise. King expressed deep suspicion about the intentions of the leaders of the Catholic Church, commenting on the history of ultramontanism and its goals in Europe and Canada. He defended the school system in thoroughly liberal terms: it offered equality, efficiency, and common opportunity. His conclusion was a declaration of war: “If we once abandon the strong line of defence that is along the heights of equality . . . the end will be the overthrow of our rights and independence of action.” An amendment to repeal the school act was defeated by 24 to 12 and a motion against federal and imperial interference in the matter carried by virtually the same margin. On this note Tilley, now lieutenant governor of the province, dissolved the assembly.

The 1874 election in New Brunswick was the schools election. There was no other issue. The centre-piece of the campaign was King’s speech at Saint John, which James Hannay claimed largely contributed to his success. It contained the refrain “The ticket, the whole ticket, and nothing but the ticket.” King’s government won 36 of the 41 seats. It was the most decisive victory achieved by any New Brunswick leader in the 19th century. It was also a Liberal victory. Whatever else free school supporters stood for, they were overwhelmingly Liberals. One month after the election the Catholic appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, where King had acted as counsel for the province, was lost.

The schools issue culminated in the Caraquet riots of January 1875, in which two men died [see Robert Young]. A growing realization that the intransigence of both sides was responsible for the tragedy led the government and the Catholic Church to seek a solution to the impasse. That spring the five Catholic members of the assembly, headed by Kennedy Francis Burns*, brought forward several proposals prepared by Sweeny. They asked that Catholic children be allowed to attend schools outside their districts, that members of religious orders be trained and examined separately, that the bishop in each diocese be able to prevent the use of any text he found to be offensive, and that Catholic children be given religious instruction after school hours, the hours of regular instruction to be reduced to accommodate it.

The proposals were studied – and probably debated – at length by the government. On 6 August the Executive Council responded. The attendance of children at schools outside their districts was a matter for the school trustees. Members of religious orders would not have to attend the Normal School but would have to write common examinations with those who did. The bishops would not be permitted to determine the texts used in any public school; however, offensive passages in the prescribed English history text would be altered. Religious instruction could be carried out in school buildings owned by the Catholic Church which the local school trustees had agreed to rent and use as public schools. The regular instructional day could not be shortened for this purpose. The effect of the last two conditions was to limit Catholic instruction to a few urban centres and to throw the debate back to the local school boards. Later the same day the council met as the Board of Education and adopted regulations to institute the changes. Even these limited concessions were so controversial that the new regulations, in which the bishops reluctantly acquiesced, were not made public and the schools act itself remained unchanged.

The schools act of 1871 was the most significant piece of social legislation in 19th-century New Brunswick. It provided a common training for every child and established the principle that the state had a responsibility to ensure equal access to basic education. When King left office in 1878 the number of children enrolled in the public school system had more than doubled and the number of public school teachers had increased by half.

King’s final years as premier were comparatively peaceful. His last major piece of legislation was the Municipalities Act of 1877, in its own way as far-reaching in its implications as the schools act. Since few counties had chosen to incorporate as municipalities, most New Brunswickers lived in communities where administrative and judicial authority was exercised in the 18th-century tradition of magistrates appointed by the provincial government. King’s act obliged counties to incorporate and thus permitted a far greater measure of democratic control of the agencies of government. It also made the county councils financially responsible for the needs of the locality, an important consideration for a provincial administration with a limited tax base. The structure established in 1877 remained the basis for municipal government in New Brunswick until it was dismantled 90 years later by another liberal reformer, Louis-Joseph Robichaud.

King had long been one of Leonard Tilley’s men. They shared a common Saint John perspective; both participated in the moderate reform movement found in the city from the 1840s; both were liberal evangelicals. As the federal election of 1878 approached, Tilley prepared to leave Fredericton and assume his traditional role of New Brunswick chieftain in any Conservative administration in Ottawa. It seems clear that he now saw the much younger King as his successor in this position. They decided to run as Liberal Conservatives in the constituencies of Saint John City and Saint John City and County respectively.

King resigned as attorney general and government leader on 3 May. Grasping Tilley’s strategy for recapturing the Saint John constituencies, the federal Liberal government offered King a position on the New Brunswick Supreme Court, which he refused. Tilley confidently predicted that the Conservatives would easily carry at least two of the three Saint John seats. He was wrong. There was deep suspicion in Saint John of Macdonald’s tariff policies, and King was a traditional New Brunswick Liberal running under a Conservative banner in a constituency where many Conservatives were Catholics still smarting from the schools issue – and he was running against a Liberal cabinet minister, Isaac Burpee*. In the end Tilley barely took his seat and King was defeated.

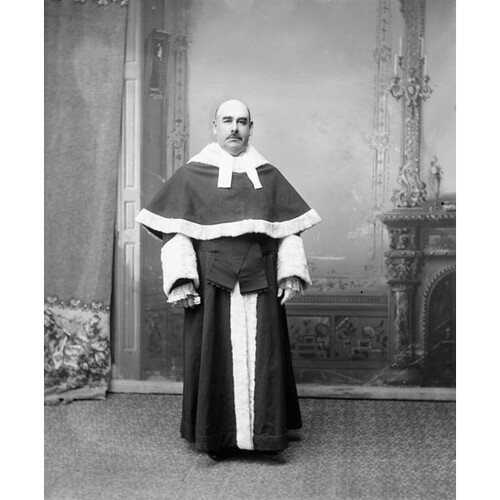

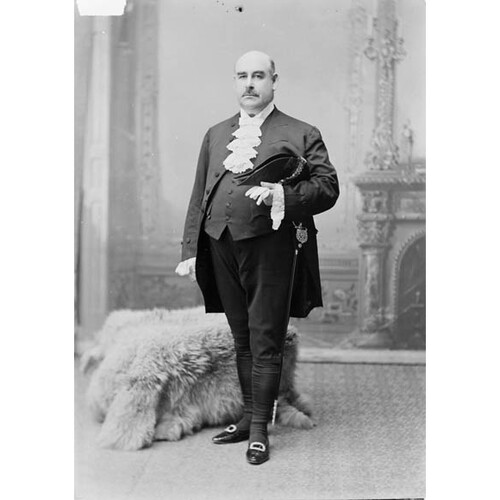

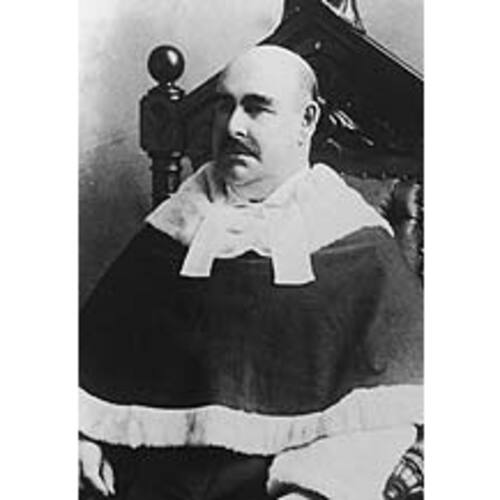

King remained out of public life for the next two years. On 9 Dec. 1880 he was appointed to the Supreme Court of New Brunswick. Although the judgeship was almost certainly a reward for his services to the Conservative party in 1878, and was probably obtained through Tilley, it was an excellent appointment. An intellectual by inclination, King quickly established himself as the ablest man on the court and acquired an enviable reputation for the quality of his judgements. In 1882 one of the fiercest critics of the New Brunswick bench, Jeremiah Travis*, praised him in the following terms: “King promises to make a good judge. I never heard a question raised as to his entire honesty. He is a very clear thinker; readily apprehends the strengths of points presented to him, and is a very clear, logical and close reasoner . . . his judgments will almost necessarily be sound legal decisions. If I had King and [Acalus Lockwood] Palmer with me on a question of law, my views would not be much unsettled if I had the whole of the other four [judges] against me.” King served on the court for 13 years, and also taught in the Saint John Law School (now the University of New Brunswick faculty of law) in 1892–93.

He was called to the Supreme Court of Canada on 21 Sept. 1893. His reputation within the legal community was such that the appointment had long been expected and was favourably received. Chief Justice Sir Samuel Henry Strong described him as “a great lawyer . . . probably the best commercial lawyer in the Dominion.” In this connection he was appointed in 1896 to the Anglo-American arbitration commission created to deal with claims for damages incurred when Americans seized Canadian and British sealing vessels in the Bering Sea [see Clarence Nelson Cox].

King died in Ottawa on 7 May 1901 at the age of 61 and was buried in Fernhill Cemetery, Saint John. His wife survived him by more than 35 years.

George Edwin King left no personal papers. The best primary sources for his career are the Saint John, N.B., newspapers, notably the Daily Telegraph, the Morning Freeman, and the Saint John Globe, 1867–78; the minutes of the Executive Council of New Brunswick, 1869–78, found in PANB, RS6, A; the House of Assembly Journal, 1866–78, Reports of the debates, 1867–70, and Synoptic report of the proc., 1874–78. The papers of the New Brunswick Supreme Court, 1880–93, are held in PANB, RG 5.

NA, RG 31, C1, 1851, Saint John. PANB, MC 1156; RS71, 1901, G. E. King. W. M. Baker, Timothy Warren Anglin, 1822–96: Irish Catholic Canadian (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1977). Canadian biog. dict. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). CPG, 1873–97. K. J. Donovan, “New Brunswick and the federal election of 1878” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., Fredericton, 1973). Hannay, Hist. of N.B. K. F. C. MacNaughton, The development of the theory and practice of education in New Brunswick, 1784–1900: a study in historical background, ed. A. G. Bailey (Fredericton, 1947). N.B., Acts, 1869–78. Snell and Vaughan, Supreme Court of Canada. G. F. G. Stanley, “The Caraquet riots of 1875,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 2 (1972–73), no.1: 21–38. P. M. Toner, “The New Brunswick separate schools issue, 1864–1876” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., 1967). Vital statistics from N.B. newspapers (Johnson). C. M. Wallace, “The life and times of Sir Albert James Smith” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., 1960); “Sir Leonard Tilley, a political biography” (phd thesis, Univ. of Alta, Edmonton, 1972).

Cite This Article

T. W. Acheson, “KING, GEORGE EDWIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/king_george_edwin_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/king_george_edwin_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | T. W. Acheson |

| Title of Article: | KING, GEORGE EDWIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |