Source: Link

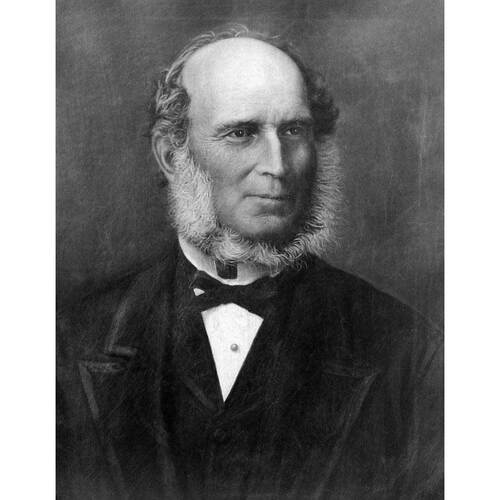

WILMOT, LEMUEL ALLAN, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 31 Jan. 1809 in Sunbury County, N.B., son of William Wilmot and Hannah Bliss; d. 20 May 1878 at Fredericton, N.B.

Lemuel Allan Wilmot’s father was a lumberman of loyalist ancestry, and his mother, who died before he was two years old, was a daughter of Daniel Bliss, a loyalist and member of the first New Brunswick Executive Council in 1784. William Wilmot, not particularly successful in business, moved to Fredericton in 1813 to found a Baptist church and to educate his children. There he acquired an interest in politics and was elected to the assembly in 1816; he was defeated in 1819 and 1820 but re-elected in 1823. Twice, however, he was denied permission to take his seat, for an act had been passed in 1818 to prevent clergymen from sitting in the legislature. As he was ejected from the house for the second time, he is reported to have said, “Sir, the time will come when that lad (pointing to him [Lemuel Allan]) will see that justice is done to my memory.” This story and another, that Wilmot overcame a speech impediment to become a great orator, form part of a mythology that enveloped Lemuel Allan Wilmot after his death and elevated him to heroic stature.

Wilmot was educated at the Fredericton grammar school and took a partial course at King’s College. In June 1825 he entered the law office of Charles Simonds Putnam; he became an attorney in 1830, was admitted to the bar in 1832, and created a queen’s counsel in 1838. As a lawyer and later as a judge, Wilmot impressed more by his style and oratory than by his logic and wisdom. His striking appearance, sharp gestures, and flowing language full of historical and biblical illustrations were combined with high emotion in most effective presentations. “When he drew his tall form up before a jury, fixed his black piercing eyes upon them, moved those rapid hands and pointed that pistol finger, and poured out his arguments and made his appeal with glowing, burning eloquence, few jurors could resist him.”

Wilmot’s admission to the bar in 1832 coincided with his marriage to Jane Ballock of Saint John. Her death the following year, “after a severe and protracted illness,” may have affected Wilmot’s religious attitudes. In 1833 he came under the influence of the Reverend Enoch Wood* of the Fredericton Methodist Church, and soon dedicated himself to the church. His marriage to Elizabeth Black in the fall of 1834 was closely related to this religious commitment. She was the granddaughter of the Reverend William Black*, “the father of Methodism” in the Maritimes. Wilmot never swayed from his new faith.

Almost as soon as he opened his law practice in Fredericton Wilmot turned his skills to politics. Successful in both a by-election and a general election in 1834, he took his seat in the assembly on 25 Jan. 1835. Neither his youth nor his surroundings inhibited Wilmot; in his first session he introduced resolutions and bills on subjects such as the Maine–New Brunswick boundary and the expenses of judges on circuit. By 1836 he was reputed to be able “to thrill and enchain legislatures” in four-to five-hour speeches. The subject of many was the crown lands office and its management by the commissioner, Thomas Baillie*. Apparently as a result of these speeches Wilmot was chosen to accompany William Crane* of Sackville to London in 1836 with specific demands for the surrender to the assembly of the remaining crown lands and of the revenue that Baillie had accumulated from earlier sales. Lord Glenelg [Charles Grant], the colonial secretary, agreed to all the requests and the crown lands were handed over in return for a permanent civil list. Of greater significance was Glenelg’s decision that the Executive Council was to be reconstructed “to ensure the presence in the Council of Gentlemen representing all the various interests which exist in the Province, and possessing at the same time the confidence of the people at large.” Glenelg was concerned not only with New Brunswick but also with the whole of British North America, and planned to use New Brunswick as the model for change. Lieutenant Governor Sir Archibald Campbell*, horrified at Glenelg’s decisions, frustrated them at every turn, so much so that Crane and Wilmot were again dispatched to London in 1837 to reaffirm their gains. The trip was unnecessary, for Campbell, whose resignation they sought, had been replaced by Sir John Harvey*, the governor of Prince Edward Island.

Wilmot returned to New Brunswick to see a civil list bill passed in the legislature and Harvey liberalize the council by the addition of assemblymen including Crane. Wilmot as yet had no claim. In the meantime he supported the governor’s struggle against the old Odell-Baillie clique, which was not easily uprooted. Wilmot’s objectives were limited to those outlined in the Glenelg dispatch and it is unlikely that he either accepted or even understood the full meaning of responsible government. Never a good party man even when he was the leader of the reform movement, Wilmot did not hesitate to desert his colleagues when government appointments were offered. His pursuit of office, first on the Executive Council, then on the bench, and finally as lieutenant governor, might well be classed as rapacious. One authority has suggested recently that even before he was in office Wilmot was part of a “new family compact” that controlled New Brunswick after 1837 to a far greater extent. than had the old compact. As an example, when George Pigeon Bliss, the receiver general, died leaving his accounts short by £7,000, Wilmot and other Bliss relatives prevented the crown from seizing his assets. On another occasion, Wilmot, attacked in the press for his “usual effrontery and disregard for the truth,” had the journalist, John A. Pierce, committed to common jail for his “gross and scandalous libel.” Pierce had been criticizing Wilmot for some time and the latter proved remarkably sensitive to attack. In 1840 the Saint John Chronicle, which referred to Wilmot as “That inflated bladder of wind,” attacked the lieutenant governor, and it too was taken to court. Harvey had not wished to pursue the matter, but Wilmot and others insisted. This case was lost as was a final one in 1844, when Wilmot was again criticized. In a negative way he thus contributed to the freedom of the press for the courts settled the issue by ruling against assembly decisions.

From 1837 until 1843 Wilmot participated actively in the assembly. The smart phrases of the Durham Report and the popularization of the ideas of responsible government provided him with the necessary slogans, yet Charles Fisher of York County, the leading constitutional expert in the province, was the only New Brunswick politician who treated the subject at an elevated level. Wilmot’s devotion to the principle of responsible government was questioned by his contemporaries and remains hypothetical.

Under Sir William Colebrooke*, the new governor, an election was held early in 1843. Wilmot paraded the country with statements on responsible government, yet in New Brunswick, as in the rest of British North America, these were not the sort of issues that captivated the public imagination. Colebrooke, a moderate reformer himself, and aware of the diversity in the assembly, set about to form an all-factions Executive Council that undoubtedly had the support of the majority in the assembly. It included, among others, Edward Barron Chandler, Robert Leonard Hazen, Hugh Johnston* and Wilmot. Wilmot’s presence required little if any soul searching. To him taking office was a logical outcome of the Glenelg approach and probably satisfied his interpretation of responsible government. There was not much consternation at the time, although a liberal historian has written: “Mr. Wilmot certainly lost prestige by his action on this occasion, as he did subsequently from the display of similar weakness.”

Colebrooke’s limited acceptance of the new system soon forced Wilmot out of the council. On Christmas Day 1844 William Franklin Odell*, the provincial secretary, died. Before the sun had set Wilmot was at Colebrooke’s door to inform him that Odell’s position must be filled by a member of the assembly holding a seat on the Executive Council. Colebrooke, unwilling to make such a concession, appointed his son-in-law, Alfred Reade. The British government later declared the appointment invalid; in the meantime Chandler, Hazen, Johnston, and Wilmot resigned from the council. The first three stated that they had resigned because of Reade’s unsuitability for the position; Wilmot had two reasons. The first was “that all the offices of honour and emolument in the gift of the administration of the government should be bestowed upon the inhabitants of the province.” The second was that he supported British practices “which require the administration to be conducted by heads of departments responsible to the legislature . . . .” Colebrooke formed a new council and retained it even after the assembly passed by 23 to 10 a resolution that it did not possess “the confidence of the House nor the Country at large.”

Out of office, Wilmot took on the appearance of the leader of the opposition and, although his position changed from issue to issue, he regularly pressed for the initiation of money grants by the executive.

Another of his interests was King’s College. Between 1839 and 1846 he introduced a series of bills for some liberalization of the college. Only in 1846 was a minor revision accepted. Later he worked closely with Charles Fisher on a total revision which resulted in the creation of the University of New Brunswick in 1860. A related issue was a non-sectarian public school system and to this he gave untiring support. “It is unpardonable that any child should grow up in our country without the benefit of, at least, a common-school education,” he stated in 1852. “It is the right of the child. It is the duty not only of the parent but of the people; the property of the country should educate the country . . . .” As lieutenant governor of New Brunswick in the 1870s he assisted in the passage of a school act fulfilling many of his own aims.

The nature of the political system was, however, the overriding issue of the 1840s. An election of 1846 returned many new members, and Wilmot confidently expected an invitation into the government. It came; in fact, he was the first offered a seat in council. After “much deliberation” he accepted, if “four professing his own opinion, whom he would be prepared to nominate, were appointed in a cabinet of nine.” From this distance it is difficult to determine which was the greater-Colebrooke’s relief at being able to refuse or Wilmot’s dismay at the rejection. Chandler, Hazen, and Johnston returned to the government, and the “new compact,” without Wilmot, governed with the support of the majority.

Over the next few months Wilmot’s action as provocateur reached its height, especially during the debate on a motion of want of confidence in 1847. On 25 March 1847 he appeared at his best and his worst in a long, colourful, but rambling speech full of high sentiment and scorching personal references. George Edward Fenety* reported the speech: “A good deal had been said about politics and political principles; but his political principles were not of yesterday – he had gleaned them from the history of his country which they were all proud to own. Would any hon. member dare to tell him that because we were three thousand miles from the heart of the British Empire, that the blood of freemen should not flow through the veins of the sons of New Brunswick?” Almost in the next breath he could turn to a slashing personal attack on Hazen. Much of the speech was responses to interjections and chatter in the house. Fisher’s constitutionally sound speeches lulled to sleep those who stayed; Wilmot’s appeal to the converted and unconverted filled the house and few came through the experience unaffected. The motion of 1847 was lost 23 to 12.

This exercise of 1847 was really the last of its type for Wilmot. Sir Edmund Walker Head* became governor in 1848, with instructions to follow the dispatch of Earl Grey to Sir John Harvey of Nova Scotia requiring that the council be “men holding seats in one or other House, taking a leading part in political life, and above all, exercising influence over the Assembly.” Head immediately set about to form a coalition “of the ablest Liberals with the preponderantly powerful Conservatives.” Wilmot and Fisher thus joined Chandler, Hazen, John Simcoe Saunders, William B. Kinnear*, and John R. Partelow*. Head had wanted Wilmot to become provincial secretary, but he refused and insisted on being appointed attorney general, the logical stepping stone to the Supreme Court. Wilmot did hasten to assure Chandler that the latter’s “claims for the Bench are undoubted.”

Wilmot and Fisher were accused of deserting their principles in 1848. “All hope of radical change, with the loss of two of the ablest standard bearers of the party, now vanished,” lamented Fenety. “It was almost worse than useless to contend longer for equal political justice, when the leading champions of the party had joined the standard of the enemy . . . . This was the great political mistake of their lives.” From this point of view, responsible government was not introduced into New Brunswick in 1848 and the major reason was the Wilmot-Fisher betrayal. Both men, however, believed they were entirely consistent with their principles. The Glenelg settlement had created a spirit of moderation which bridged the gap between 1837 and 1848. Chandler Hazen, Wilmot, and Fisher were products of a system that achieved most of the features of responsible government without the necessity of political parties. In addition, all preferred coalitions. Wilmot, moreover, was merely rejoining his colleagues of 1843 and 1844. The government formed in 1848 unquestionably had the support of the majority in the assembly and retained it until 1854.

Wilmot as attorney general (1848–1851) was a disappointment to even the most faithful. His principal achievement was an act for the consolidation of the criminal law, “a useful but not a brilliant work.” Some practical changes were made to assist municipalities, and as chairman of the committee on agriculture he rendered good service. On the whole, however, Wilmot’s primary function was to present and defend the position of the government in the assembly. There he frequently found himself on the receiving end of sharp barbs from former colleagues, especially William Johnstone Ritchie* of Saint John. On other occasions he took action not approved by the government but which he seemed called upon to pursue to retain political support. Goaded by Ritchie, for instance, he pressed legislation to lower the salaries of public officials, especially those of judges. In general, it is difficult to find consistency in his stand on issues. He voted against Fisher’s bill requiring members to vacate seats on accepting appointments. He supported railway construction, but saw no conflict of interest between the Intercolonial and the European and North American line to the United States. In 1850 he made the major speech at the Portland convention in support of the latter [see John Alfred Poor]; that same year he accompanied Head to Toronto to discuss the Intercolonial. Wilmot had attended the first British North American intercolonial conference at Halifax in 1849 and seems then to have become a supporter of a union. At that same conference he offered to throw the whole inshore fisheries open to the Americans in return for reciprocity, and in 1850 he and Head were in Washington to explore possibilities.

Wilmot was never defeated at the polls, but in the election of 1850 he barely scraped into the assembly. Fisher was defeated. Wilmot may well have come to view his position as precarious and have realized that he had lost touch with New Brunswick politics. Governor Head was not enamoured with him, especially after his action concerning the salaries of judges. “If the Attorney General choose to resign, because he is offended by the expression of my opinion,” wrote Head to Grey, “he must do so.” A defrocked Wilmot might be a menace in the house, but Head did not believe he would resign. An escape for both was provided with the resignation of the chief justice, Ward Chipman*, on 17 Oct. 1850.

“I expect My Government here to break up in a scramble for the Chief Justiceship,” Head wrote a friend the same day. The scramble, with one exception, failed to take place; the exception was Wilmot. The Executive Council decided not to add to the bench, considering the three remaining judges adequate for the work. Only Fisher, Kinnear, and Alexander Rankin* dissented. The day the council made its decision, most of the members left Fredericton for their homes. That evening Wilmot composed a letter to Head: “I certainly think we have not acted wisely in the advice given by our minute today, and I am now disposed to retract the opinion therein expressed.” The next day he read his letter to Head. The encounter made it clear that Head would decide “on his own responsibility and not necessarily on that of his Council,” and that Wilmot would accept appointment to the bench regardless of any problems over responsibility or principle. Secretly, Head had James Carter appointed the chief justice and Wilmot a puisne judge. In January 1851 this news was sprung on the province in a special edition of the Royal Gazette.

After all possible rationalizations have been considered, it remains that Head and Wilmot between them sacrificed the essence of responsible government. Yet only Fisher resigned from the council for the principle, and he had lost his seat in the assembly and had no choice. It may be that New Brunswick was not ready for responsible government; it is more likely that the system was not well served by the two men, Head and Wilmot, who had the power to make it succeed. The other members of the council served the principle no better, but they had not committed themselves to it as had Wilmot.

From 1851 until 1868 Wilmot was a judge; apparently he served well but gained little distinction. No great decisions are on the record nor are there any blotches. He remained before the public to a far greater degree than most judges, however, and his other interests brought him into prominence: the Methodist church, the militia, educational changes, and confederation.

Wilmot was the first non-conformist to hold the office of attorney general and to be appointed to the bench. For these reasons if for no others he would have been important among the dissenters, but he took his church work more seriously than any of his other endeavours. He was the main pillar of the Fredericton Methodist (now Wilmot United) Church. Following a fire in 1850 he headed a movement to construct a much larger church of modern design. He had in addition been choir director from 1845 and was superintendent of the Sabbath school for most of his adult life.

During these same years Wilmot gave frequent and popular public lectures. In Saint John in 1858 over 2,000 came to hear “The most eloquent lecture I have ever listened to.” His range of subjects was quite wide. It might be “Havelock’s March to Lucknow,” the public school system, the evil of Darwin, or the dangers of alcohol, though he does not appear to have been a prohibitionist.

Wilmot’s missionary zeal was kept for common schools. Undoubtedly he supported an education for everyone, but he wished to eliminate Roman Catholic influences from the schools. His strong anti-Catholic and anti-French positions were public knowledge. As a judge he was severely reprimanded for a speech on a priest who flogged a boy for reading the Bible. When he was lieutenant governor in the 1870s a public school act was passed – the product, according to the Catholic press, of Pope L. A. Wilmot and his half-dozen Methodist cardinals. Wilmot’s view of the French had been stated firmly in 1837: “Lower Canada would [not] be tranquillised and restored to a proper state, till all the French distinguishing marks were utterly abolished, and the English laws, language and institutions, universally established throughout the Province.”

As a young man Wilmot had joined the York County militia and quickly rose to the rank of major. When the Aroostook War threatened in 1838–39 Wilmot at the head of his troop was patrolling the banks of the Saint John River. That was as close as he got to battle; he remained ready, however, and was a battalion commander at the first militia camp in the province in 1862. Lieutenant Governor Arthur Hamilton Gordon* was favourably impressed and promoted him to lieutenant-colonel on 1 Jan. 1863.

Wilmot’s public activity was most strikingly displayed when confederation, which he fully supported, was mooted. “Keep your eye on the Pacific,” was his theme. Wilmot and Samuel Leonard Tilley*, the government leader in 1864, had come to know each other in the 1850s and had participated in a lecture series in 1860. Shortly after the Quebec conference, Tilley consulted Wilmot over an approach to the public. “You must not lay too much scope on the financial adjustments,” he told Tilley. Stress the “great future,” and “national greatness.” When Tilley was defeated by Albert James Smith* a few months later, Wilmot’s position became uncomfortable. Smith reprimanded Wilmot for his strong pro-confederation statement before a grand jury. The office of chief justice twice became open and Wilmot was twice passed over, the second time for a junior judge and former antagonist, W. J. Ritchie. Even his cousin, Robert Duncan Wilmot*, who was on the Executive Council, could not assist him.

The eventual success of the confederation movement led to Wilmot’s appointment as the first native-born lieutenant governor of New Brunswick. Tilley had written John A. Macdonald* on 3 Oct. 1867 requesting it, but it was not granted until nine months later, on 23 July 1868, and only after Tilley’s continual pleadings. During his five years as lieutenant governor, Wilmot conducted himself well, pleasing even those who had been opposed to him. The University of New Brunswick, which owed much to him and on whose senate he served from 1860, awarded him an honorary dcl during this period.

Wilmot retired to his gardens at “Evelyn Grove,” Fredericton, when Tilley succeeded him as lieutenant governor on 15 Nov. 1873. He served on the commission to settle the Prince Edward Island land claims, and he was appointed arbitrator in the western Ontario boundary dispute. Before the commission got underway, he died of a heart attack on 20 May 1878.

Few New Brunswick figures are better known than Lemuel Allan Wilmot. He is bracketed with Joseph Howe, Robert Baldwin*, and Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* as a central personality in the struggle for responsible government. The city of Fredericton commemorates him with a church, a park, and several buildings. An examination of his career, curiously, does not reveal the reasons for this high reputation. As a politician and a judge he was not particularly notable. His legislative record was not impressive. His devotion to principles was tenuous at best, and he betrayed responsible government. How then can his eminence be explained? It seems to rest on three components.

As a public speaker Wilmot ranked with the best of his time. He thrilled audiences long after he had left the political scene and long after they had forgotten what his contribution had been. By the time he had become lieutenant governor, he was almost an institution.

Of more importance was his religion. He became prominent in his province as a nonconformist, proudly parading his religion all the way. In 1880 the Reverend John Lathern*, a Methodist clergyman and editor, wrote a eulogistic biography in which the whole of Wilmot’s career was treated as a service to God, church, and country. Few New Brunswick politicians had biographies; no other was interpreted in providential terms. For over 25 years Lathern’s remained the standard work on Wilmot. In 1907 James Hannay*, writing for the Makers of Canada series, started with Lathern’s book as a solid foundation and erected on it the Whig-Liberal interpretation demanded by the series. Its preoccupation with responsible government as the great Canadian achievement assumed a Howe or a Baldwin in New Brunswick and Hannay obligingly produced Wilmot. Even with this sanguine approach, however, Hannay had difficulty forcing Wilmot into the mould. His humble youth and distinguished later years served admirably, but the main body of the career lacked the essential ingredients. In preparing the 1927 edition of the text, George Wilson felt it necessary to stress some of the problems in the preface and to add a 16-page appendix. The Hannay biography, nevertheless, remained unchanged. Sixty years after its publication it was still the authority.

Wilmot’s reputation, in the final analysis, is decidedly inflated. He was a first-rate stump politician who failed to live up to the promise of his early career. His greatest success was in using his political influence to acquire prestigious appointments for himself – a practice that was normal in his era. His biographers, by attempting to create a man he never pretended to be, have spawned the view that he was a lesser man than he might have been.

[Lemuel Allan Wilmot’s papers are scattered throughout other collections, and are incomplete. The following contain material on Wilmot: N.B. Museum, Edward Barron Chandler papers; Webster coil.; R. D. Wilmot, Record-books, 1868–85. PAC, MG 24, B29 (Howe papers); MG 26, A (Macdonald papers); MG 27, I, D15 (Tilley papers). PRO, CO 188 University of New Brunswick Library, Archives and Special Collections Department, Arthur Hamilton Gordon papers, 1861–66.

For printed primary sources see: New Brunswick, House of Assembly, Journals, 1835–50; Synoptic report of the proceedings, 1835–50. Globe (Saint John, N.B.), 1858–73. Morning Freeman (Saint John, N.B.), 1861–73. Morning News (Saint John, N.B.), 1839–65. New Brunswick Courier (Saint John, N.B.), 1842–62. New Brunswick Reporter (Fredericton), 1844–78.

Among printed sources G. E. Fenety’s Political notes and observations is essential and his “Political notes,” Progress (Saint John, N.B.), 1894, collected in a scrapbook at the N.B. Museum and PAC, are of some use. J. W. Lawrence’s Judges of New Brunswick (Stockton) is also a valuable source.

Biographical notices of Wilmot appear in the following: Appleton’s cyclopædia of American biography, ed. J. G. Wilson et al. (10v., New York, 1887–1924), VI; Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, III; DNB. The only two biographies of Wilmot were written by people who knew him: John Lathern, The Hon. Judge Wilmot: a biographical sketch, intro. D. D. Currie (rev. ed., Toronto, 1881), and James Hannay, Lemuel Allan Wilmot (Makers of Canada series, Anniversary ed., [VIII], London and Toronto, 1926). Hannay presents his view of Wilmot in a shorter form in his History of New Brunswick, II. Though useful, Lathern and Hannay must be approached with caution. W. S. MacNutt provides a major revision on Wilmot in New Brunswick: a history as does D. G. G. Kerr in Sir Edmund Head, a scholarly governor, with the assistance of J. A. Gibson (Toronto, 1954).

Of some use is G. E. Rogers, “The career of Edward Barron Chandler – a study in New Brunswick politics, 1827–1854,” unpublished ma thesis, University of New Brunswick, 1953.

The following articles should be consulted: D. G. G. Kerr, “Head and responsible government in New Brunswick,” CHA Report, 1938, 62–70; and W. S. MacNutt, “The coming of responsible government to New Brunswick,” CHR, XXXIII (1952), 111–28; “New Brunswick’s age of harmony, the administration of Sir John Harvey,” CHR, XXXII (1951), 105–25; “The politics of the timber trade in colonial New Brunswick, 1825–40,” CHR, XXX (1949), 47–65. c.m.w.]

Cite This Article

C. M. Wallace, “WILMOT, LEMUEL ALLAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wilmot_lemuel_allan_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wilmot_lemuel_allan_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. M. Wallace |

| Title of Article: | WILMOT, LEMUEL ALLAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |