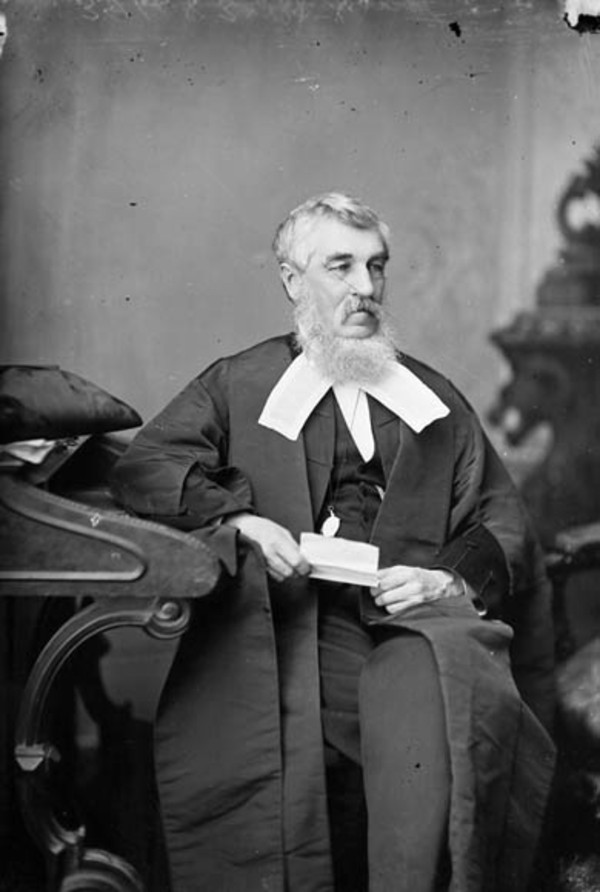

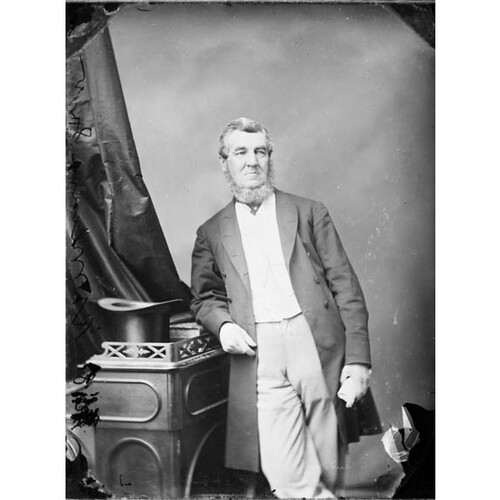

WILMOT, ROBERT DUNCAN, businessman, politician, and lieutenant governor; b. 16 Oct. 1809 in Fredericton, son of John McNeil Wilmot* and Susanna (Susan) Harriet Wiggins; m. 17 Dec. 1833 Susannah (Susan) Elizabeth Mowat of St Andrews, N.B., and they had seven children; d. 13 Feb. 1891 at Belmont, his estate in Sunbury County, N.B.

When Robert Duncan Wilmot was about five years old, his family moved to Saint John where his father became a prominent merchant and shipowner. Young Wilmot was educated in local schools and then entered his father’s business. He spent the years 1835–40 in Liverpool, England, representing the firm. After his return he was involved in the construction of mills, ships, and railways, and was one of the promoters of Saint John as the metropolis of New Brunswick. A member of the board of the New-Brunswick Colonial Association and a director of the European and North American Railway, he is considered by historian Thomas William Acheson to have been one of the 40 merchants who “dominated the commercial life of the city between 1820 and 1850.”

Wilmot was introduced to politics at a young age. He belonged to an old tory family and his father represented Saint John County and City in the House of Assembly for 15 years. R. D. Wilmot entered both municipal and provincial politics in the 1840s. He served for a while as an alderman and was mayor of Saint John in 1849–50. The most difficult problem he had to deal with as mayor was an Orange riot. There had been violence in previous years when the Orangemen had marched on 12 July to celebrate the battle of the Boyne. When it became known that they would proceed through the Catholic districts in 1849, Wilmot asked them not to march but, since there was no law banning public processions, he could do little to stop them. Irish Catholics erected a pine arch over one of the streets the procession had to use so that the Orangemen would have to dip their colours. Accompanied by a magistrate and a constable, Wilmot tried to remove it. He was then assaulted by the crowd and ordered out of their territory. After one final attempt at persuading the Orangemen to avoid the Catholic area, Wilmot called on the military for aid. Before the commander positioned the soldiers effectively, however, several people were killed.

Wilmot was first elected to the assembly in October 1846 for Saint John County and City, and he took over from his cousin Lemuel Allan Wilmot* the role of spokesman for provincial interests favouring protectionist trade policies. He served in the house continuously for 15 years before being defeated in 1861. Re-elected in 1865, he remained a member of the assembly until confederation.

In 1850 Wilmot was returned as an opponent of the government and was called by some a liberal, but within a year he accepted the office of surveyor general in the conservative government of John Ambrose Sharman Street*. This would not be the only time he changed sides in politics. After taking office as surveyor general, he had to resign his seat and seek re-election. He was condemned by the other members from Saint John who had been his allies in the recent general election. To their great surprise, Wilmot was returned by his constituents. Samuel Leonard Tilley, Charles Simonds*, and William Johnston Ritchie then resigned on the grounds that they themselves must have lost the confidence of Saint John voters. Wilmot remained as surveyor general until 1854. He continued to show his conservatism by opposing measures such as the attempt to introduce the ballot system in 1853. In October 1854 reformers were able to pass a motion of non-confidence in the administration for not acting in accordance with the principles of responsible government. Street and his colleagues resigned – the first time a New Brunswick government had left office because it lost a vote in the assembly. In spite of conservatives such as Wilmot, responsible government had finally come to the province.

The new Reform administration, led by Charles Fisher* and Tilley, passed a bill introducing the ballot system, which Wilmot still opposed, but they soon ran into trouble over their Prohibition Act, and Lieutenant Governor John Henry Thomas Manners-Sutton* succeeded in forcing them out of office. In 1856 the Conservatives were back in power. In this short-lived administration led by John Hamilton Gray*, Wilmot served as provincial secretary from 1856 to 1857. The government’s chief objective was to throw out the Prohibition Act. Once that was done, there seemed little to hold the administration together, and defeat came quickly in 1857. In the ensuing elections, however, Wilmot was once more returned.

Following his defeat in the 1861 contest, which renewed the Reformers’ mandate, Wilmot retired to Belmont, where he concentrated on raising cattle and swine. In 1865 he re-entered politics and in March was elected as an anti-confederate. In attempting to form a government after this election, Lieutenant Governor Arthur Hamilton Gordon* called first on George Luther Hatheway*, who declined the honour, and then on Albert James Smith* and Wilmot, who accepted. Wilmot, a member of the executive without portfolio, found himself overshadowed by Smith and Timothy Warren Anglin. This weak government, which was described in the newspapers as a “queer admixture of Tories and Liberals,” was united only in its desire to stop New Brunswick’s entry into confederation under the terms proposed at the Quebec conference of 1864. Many of its members favoured some sort of union, but they could not agree on the type: a number, like Smith, favoured the reservation of much more power for the provinces than the Quebec terms gave; others, like Wilmot, felt the provinces should be stripped of almost all their authority. As early as 1858 he had voiced his hope for a union that would eliminate provincial legislatures.

Never one to hide his feelings, Wilmot was soon expressing his dissatisfaction with various decisions made by Smith and his colleagues. He had hoped to move on from the government to become auditor general, but after the legislature voted to reduce the salary that went with the position, it ceased being attractive to him. The choice of W. J. Ritchie as chief justice of New Brunswick particularly angered him. With some justification, he felt that this position should have gone to the senior judge in the province, his cousin L. A. Wilmot. He was ready to resign from the government, but Lieutenant Governor Gordon wanted him to stay on. Wilmot’s views on union had changed, partly as a result of the trade conference he had attended at Quebec in September 1865. He had become convinced that a legislative union was impossible because of the division between English- and French-speaking Canadians. He also began to see that the United States would not renew reciprocity arrangements with British North America and that the political status quo could not be maintained if new markets were to be established. He returned to New Brunswick virtually a federalist. Gordon saw him, therefore, as a valuable source of division in the anti-confederate ministry.

Early in 1866 the New Brunswick representatives were selected for a British North American delegation that would go to Washington in February and discuss trade. Wilmot expected to be included since he had attended the trade conference in Quebec. He had experienced many real and imaginary slights from Smith but his exclusion from the delegation was the last straw. He immediately repeated to Gordon his wish to resign. Gordon delayed accepting the resignation and Smith had to leave for Washington. Gordon then discussed the matter with confederate leaders, Tilley and Peter Mitchell.

The Washington negotiations failed: the American government showed no interest in the revival of reciprocity, and Western Extension, the scheme to build a railway into the United States from New Brunswick, was therefore dead. Smith’s economic alternative to confederation had been shown to be unrealizable. With the government becoming more and more unpopular, in mid February Gordon tried a little blackmail on Smith. If he would accept union, Gordon would accept Wilmot’s resignation. If not, Wilmot and others would be asked to form a new government. Under this pressure Smith agreed to a mention of support for union in the throne speech of March 1866, and Wilmot’s resignation was consequently accepted. The short paragraph in the speech was ambiguous, but the Legislative Council’s address in reply was firmly in favour of a union based on the Quebec scheme. Gordon tried to get Smith to agree to his response but, perhaps feeling he was being manœuvred into a position he could not support and knowing there was no agreement amongst his colleagues on a scheme for union, Smith refused. Gordon then responded warmly to the address on 7 April and a few days later Smith’s government resigned.

The lieutenant governor now had the opportunity to get a ministry which would support confederation. Relying on the advice of Mitchell, he asked Tilley to form a new administration. Tilley, who did not have a seat in the assembly, declined. Gordon next called on Wilmot and Mitchell, who took office on 14 April. The success of the confederation project then depended on the election called for May and June. Mitchell, Wilmot, and Tilley won a sweeping victory. In July they proceeded to London, where the final terms of union were agreed to and the British North America Act was drafted.

With the formation of the federal government Wilmot was appointed on 23 Oct. 1867 to Canada’s first Senate. In 1878 he became a minister without portfolio in Sir John A. Macdonald’s government, and on 8 Nov. 1878 he was named speaker of the Senate, a position he held until he resigned on 10 Feb. 1880 to become lieutenant governor of New Brunswick as the successor to Edward Barron Chandler*. He handled the speakership efficiently but he made no major contributions to the Macdonald government as a member of cabinet. While lieutenant governor, Wilmot continued his already demonstrated concern for patronage and power, and there was some criticism of his making appointments to offices of political significance without consulting the Executive Council. On the completion of his five-year term he was succeeded by Tilley.

Wilmot was an honest, able man with a strong personality who saw himself as a leader, although in the Smith and the Tilley-Mitchell governments he was overshadowed. Never an eloquent speaker, he was none the less a capable administrator and an efficient public servant. He was a rather cold man who was not widely liked. His frequent changes of view did not make him popular with more committed politicians, and historians such as James Hannay*, Peter Busby Waite, and Carl Murray Wallace have accused him of being a political opportunist. Perquisites and power do seem to have played a part in the manœuvres that took place in 1865–66. Wilmot wanted to be premier and perhaps, as Waite has said, “matters of patronage bulked large” in his eyes. But it does appear that he genuinely believed a man should be able to change his principles if circumstances warranted. Consistency never seemed to be of great importance to other politicians such as Sir John A. Macdonald; perhaps if Wilmot had been a more engaging person he might not have been criticized so harshly by his contemporaries and by historians.

PANB, MC 300, MS33/37, marriage licence, 17 Dec. 1833; MC 1156, II: 62; RG 1, RS348, A7, Wilmot to lieutenant governor, [1866]; RS355, Al, Wilmot to secretary of state, 9 Nov. 1885; A2, A. H. Gillmor to Wilmot, 31 May 1880; A4, extract of letter from governor general, 31 July 1882; A5, W. E. Baker to Wilmot, 28 Sept. 1883. G. E. Fenety, Political notes and observations . . . (Fredericton, 1867), 417, 456. James Hannay, The life and times of Sir Leonard Tilley, being a political history of New Brunswick for the past seventy years (Saint John, N.B., 1897). Daily Evening Globe, 14 March 1866. Daily Gleaner, 13 Feb. 1891. New-Brunswick Courier, 21 March 1840. Saint John Globe, 13 Feb. 1891. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). CPC, 1909. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery. T. W. Acheson, Saint John: the making of a colonial urban community (Toronto, 1985). D. [G.] Creighton, The road to confederation; the emergence of Canada: 1863–1867 (Toronto, 1964). James Hannay, Wilmot and Tilley (Toronto, 1907). Lawrence, Judges of N.B. (Stockton and Raymond), 268, 399, 489, 491–92, 513, 520. MacNutt, New Brunswick. Waite, Life and times of confederation, 229–62. T. W. Acheson, “The great merchant and economic development in St. John, 1820–1850,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 8 (1978–79), no.2: 3–27. A. G. Bailey, “The basis and persistence of opposition to confederation in New Brunswick,” CHR, 23 (1942): 374–97. S. W. See, “The Orange order and social violence in mid-nineteenth century Saint John,” Acadiensis, 13 (1983–84), no.1: 68–92. C. M. Wallace, “Saint John boosters and the railroads in mid-nineteenth century,” Acadiensis, 6 (1976–77), no.1: 71–91.

Cite This Article

W. A. Spray, “WILMOT, ROBERT DUNCAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wilmot_robert_duncan_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wilmot_robert_duncan_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. A. Spray |

| Title of Article: | WILMOT, ROBERT DUNCAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |