Source: Link

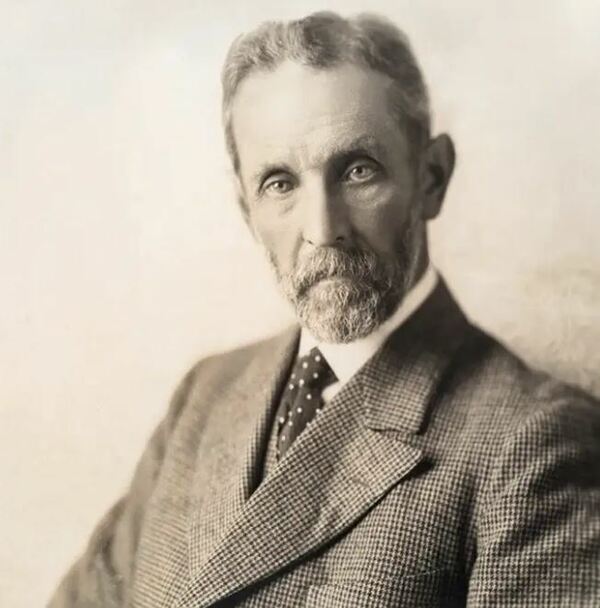

MACLURE, SAMUEL, telegraph operator, artist, and architect; b. 11 April 1860 in Sapperton (New Westminster, B.C.), son of John Cunningham Maclure and Martha McIntyre; m. 10 Aug. 1889 Margaret Catherine (Daisy) Simpson, and they had four daughters, one of whom died shortly after birth; d. 8 Aug. 1929 in Victoria.

Reputedly the first white child born in New Westminster, Sam Maclure was the eldest son of John Maclure, a Scottish surveyor who had come to British Columbia with the Royal Engineers [see Richard Clement Moody*]. Raised on the family homestead at Matsqui, Sam was educated in area schools and at Victoria’s high school. He was intent on pursuing art. After some time working as a telegraph operator and government agent, in 1884–85 he attended the Spring Garden Institute in Philadelphia, where he was most taken with architecture. Financial problems cut short his stay, however, and he returned to British Columbia. Supporting himself as a telegrapher for the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway, he studied architecture at home and produced watercolour paintings for sale. Art was more than a hobby – as an architect Maclure would produce meticulous presentation drawings and garden plats. His landscapes would evolve from harsh, linear depiction to a freer impressionistic style in which he brilliantly captured watery reflection, refracted light, and the aerial effects of mist, all of which have become a commonplace of the British Columbia artistic tradition.

In 1889 Maclure joined architect Charles Henry Clow in New Westminster. Two years later he established a brief partnership with Richard P. Sharp. Maclure’s surviving residential commissions from this period exhibit prevailing High Victorian tastes and were evidently based on pattern-books. His elopement and marriage to Daisy Simpson, at the house of his sister Sara Anne in Vancouver, may have generated more excitement than his conventional architecture.

Maclure opened a practice in Victoria in 1892. His first major project, the Temple Building for merchant Robert Ward (1893), reflects the Chicago School style. Commercial work, however, was not to form the core of his early output. Among his most successful designs were variations of the alpine house, which adapted the arts-and-crafts form to the steep slopes of Victoria’s Rockland area. Rigid symmetrical planning was a distinctive feature of these small, shingle-style bungalows, including his own house of 1899. In 1900 Maclure broke through to the patronage of Victoria’s commercial and political elite with the residence he designed for Robin Dunsmuir, a son of James Dunsmuir*. It brought him many lucrative commissions, including Government House (1901–3), a project he shared with Victoria’s leading institutional architect, Francis Mawson Rattenbury*, and James Dunsmuir’s Hatley Park residence (1907–8). His collaboration with Rattenbury would continue in the design of buildings for the Bank of Montreal in developing towns in the interior.

The period 1900–14 was the high point of Maclure’s practice. In addition to his grand projects, he executed numerous more modest residential commissions. For small cottages he utilized board-and-batten cladding or sometimes slabs of unbarked fir. His larger houses were characterized by superb, dramatic staircases and halls backlit with banks of stained glass. Maclure’s difficulty in retaining contractors to execute his meticulously detailed designs was an indication of both his insistence on high-quality materials and workmanship and his close supervision. He took pains in selecting sites, and could display admirable tact in dealing with demanding clients. Although his commissions reflected the influence of arts-and-crafts and shingle-style practitioners – his materials and axial planning show an affinity with the work of Wilson Eyre, whose circle he may have known in Philadelphia – Maclure catered more and more to the English revivalist tastes of his clientele. As a result his houses began to incorporate, in a robust, vernacular fashion, elements of the Queen-Anne style: half-timbered surfaces, tall chimney stacks, and complex roofscapes, notably, for instance, in the houses done in Victoria for wholesale merchant Biggerstaff Wilson (1905) and Charles Fox Todd (1907), son of salmon canner Jacob Hunter Todd*.

In 1903 Maclure had taken on as a draftsman Cecil Croker Fox, a former student of the premier British arts-and-crafts architect, Charles Francis Annesley Voysey. By 1905, to accommodate his growing business in Vancouver, Maclure had gone into partnership with Fox and they opened an office there, which Fox ran until he went off to war in 1915. After his death the following year, a loss that devastated Maclure, the office was closed. During their years together many Voysey elements had appeared in Maclure’s commissions, particularly in his smaller houses but most obviously in the work of the Vancouver office, which provided many estate-style houses for the prestigious Shaughnessy Heights and Point Grey areas, often in association with landscape architects such as Thomas Hayton Mawson.

During the war, a lack of work produced some financial hardship for Maclure, who, one employee recalled, resorted on occasion to selling his paintings. In the following years, with the decline of wealth and social grandeur in Victoria, large commissions became rare. Maclure was able, however, to reopen his Vancouver office in 1920, and subsequently he turned increasingly to the neo-Georgian idiom. His most flamboyant commission in this style, a house in Victoria’s exclusive Oak Bay neighbourhood for lumber baron Robert William Gibson, had been taken over from Rattenbury and completed in 1919. Among the few other outstanding buildings from Maclure’s post-war practice is the rustic-style house executed for newspaper magnate Walter Cameron Nichol in Sidney (1925). By this time Maclure’s landscape designs had gained a reputation, with many plans being produced for Jennie Foster Butchart’s famous public garden project near Victoria. Maclure died in 1929 following a prostate operation, and his ashes were taken to Matsqui. His practice in Victoria was liquidated but the Vancouver branch was continued by his partner there, Ross Anthony Lort.

Though not given to extensive travel, Maclure had always kept in touch with the outside world. There were occasional trips to San Francisco; Kirtland Kelsey Cutter, an architect in Spokane, Wash., was a close friend; and the Dunsmuirs paid for Sam and Daisy to go England to select furniture for Hatley Park. A sensitive family man and an Anglican, Maclure was renowned as an extremely generous, kind, and cultured individual, well-versed in music and literature; his wife was an accomplished pianist and a portrait painter. Both were founding members in 1909 of the Vancouver Island Arts and Crafts Society. Maclure’s work was published in the Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto), Craftsman (Eastwood, N.Y.), Studio (London), and Country Life (New York), journals that often brought him fresh ideas. He is reputed to have corresponded with architectural modernist Frank Lloyd Wright. Certainly there is much evidence of Wright in the broad overhangs of Maclure’s roofs and in his studied, geometric treatment of wall surfaces.

Sam Maclure is probably the most notable of Victoria’s architects for the quality, originality, and quantity of his work – over 350 documented commissions. So powerful was his influence that numerous schools and other public buildings in British Columbia continued to bear his characteristic hallmarks, a mixture of the shingle style and English revival, well into the 1930s. His oeuvre, especially his use of half-timbering, still sets the architectural tone of Rockland and Uplands Estates in Victoria and Shaughnessy Heights and Point Grey in Vancouver.

Paintings by Samuel Maclure are found in the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, the BCA, and the Maltwood Art Museum and Gallery, Univ. of Victoria. The bulk of his architectural plans and drawings are held in the Univ. of Victoria Arch. and Special Coll., SC075 (Samuel Maclure fonds). Details of this collection are provided in D. R. Chamberlin, Samuel Maclure: architectural drawings in the University of Victoria Archives; a catalogue, intro. Martin Segger (Victoria, 1995).

BCA, CM-B308; CM-B944, sh.1–sh.4; CM-B1641, sh.1–sh.2; PDP00153–55, PDP00161–66, PDP01844, PDP03218, PDP03629–30, PDP03773; VF87, frames 0389, 0404, 0415, 0418. City of Vancouver Arch., Add. MSS 301 (Historic sites project); Add. MSS 314 (Janet Bingham coll.); Add. MSS 713 (Richard B. Gilman coll.); Add. MSS 1015 (R. A. Lort architect fonds); CVA 106-1 (photograph of Samuel Maclure); J. S. Matthews news clippings coll., M6015 (Maclure, Samuel); Port P984 N449 (group photograph of Maclure, McColl, and McLagan families, 1900). City of Victoria Arch., 98403-31 (Bakshish Gill, “A partial inventory of the buildings erected between 1918 & 1939,” March 1983); Demolished building plans, 2-0685, 0733, 0763–64; PR 127 (R. A. Lort fonds). Daily Colonist (Victoria), 9, 25 Aug. 1929. R. A. Lort, “Castle in the country,” Daily Colonist, 6 March 1960. Janet Bingham, Samuel Maclure, architect (Ganges, B.C., 1985). “A house in Vancouver that shows English traditions blended with the frank expression of western life,” Craftsman (New York), 13 (October 1907–March 1908): 675–81. R. [A.] Lort, “Samuel Maclure, MRAIC, 1860–1929,” Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, Journal (Toronto), 35 (1958): 114–15. P. E. Nobbs, “Some developments in Canadian architecture,” Country Life (New York), 43 (1922–23), no.3: 35–41. “Recent designs in domestic architecture,” International Studio (New York), 36 (November 1908–February 1909): 124–26. E. O. S. Scholefield and F. W. Howay, British Columbia from the earliest times to the present (4v., Vancouver, 1914), 4: 1063–64. Martin Segger, The buildings of Samuel Maclure: in search of appropriate form (Victoria, 1986). Martin Segger and Douglas Franklin, Exploring Victoria’s architecture (Victoria, 1996). Carolyn Smyly, “The Maclure tradition,” Western Living (Vancouver), 8 (1978), no.6.

Cite This Article

Martin Segger, “MACLURE, SAMUEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maclure_samuel_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maclure_samuel_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Martin Segger |

| Title of Article: | MACLURE, SAMUEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2025 |