Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

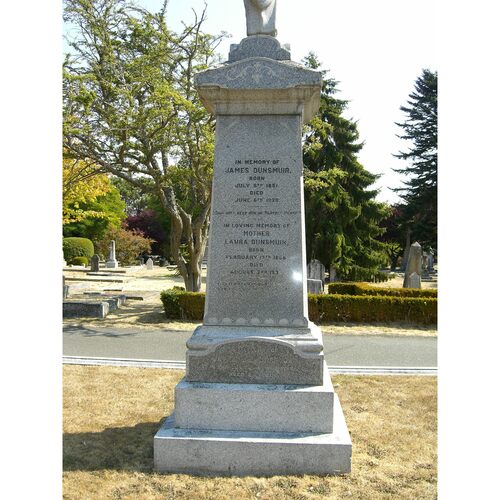

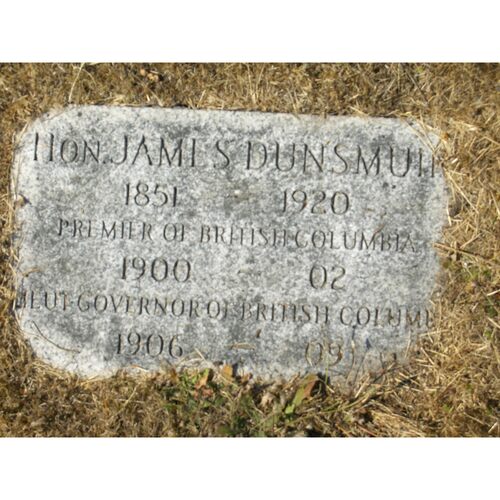

DUNSMUIR, JAMES, machinist, entrepreneur, industrialist, politician, and lieutenant governor; b. 8 July 1851 at Fort Vancouver (Vancouver, Wash.), son of Robert Dunsmuir* and Joanna (Joan) Olive White; m. 5 July 1876 Laura Miller Surles in Fayetteville, N.C., and they had three sons and nine daughters; d. 6 June 1920 at the Cowichan River, B.C., and was buried in Ross Bay Cemetery, Victoria.

Born during his parents’ emigration from Scotland to Vancouver Island, James Dunsmuir would experience his family’s rise from a crude miner’s log cabin at Fort Rupert (near Port Hardy, B.C.) to a life of wealth, prestige, and power. He received his early education in Nanaimo schools, and as he was growing up, the Dunsmuirs’ circumstances improved steadily. His father eventually obtained the position of mines’ supervisor for the Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company. In the tradition of coalmining families, where sons patterned their careers after their fathers’, James began apprenticeship as a machinist at 16, spending two years at the Willamette Iron Works in Oregon. During this period his father discovered the rich Wellington coal-seam north of Nanaimo, staked his claim, and, with the financial support of a group of naval officers, created Dunsmuir, Diggle Limited in 1873. Suddenly James’s prospects had dramatically improved. Broadening his education, he attended the Dundas Wesleyan Boys’ Institute in Dundas, Ont., for some higher learning and polish, before enrolling in 1874 to study mining engineering at the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College in Blacksburg, Va.

While in Virginia he met Laura Surles, whose brother attended the college. After their marriage in 1876, the young couple returned to Nanaimo. The Dunsmuirs’ status was demonstrated when the coastal steamer Cariboo Fly, made a special trip from Victoria to Nanaimo with the bridal party. James became mine manager for his father and Laura quickly integrated herself into the local élite, often favouring its members with songs at concerts. Less than a year later their first child arrived, to be followed by ten more during the next 17 years. Nine survived infancy. James was 52 when their youngest, a daughter, was born. Throughout the period a host of servants assisted in raising the rapidly growing family.

As manager of the Wellington mine between 1876 and 1881, James was in a difficult position. His patriarchal father was only a few miles away in the corporate and shipping office at Departure Bay, and the community knew who was really in charge. During a strike in 1877 and a fire and explosion in 1879, Robert assumed command. Indeed James always lived in his father’s shadow. Even his obituary in the Nanaimo Free Press would devote more space to the father than to the son. It would be wrong, however, to assume that a weak James mismanaged the mine and that his transfer to Departure Bay in 1881 was a demotion. In fact, under James production had risen by nearly 350 per cent, and the number of shipping wharves and rail locomotives had each increased from two to five. And working with two employees, James had created British Columbia’s first telephone from information supplied by the Scientific American; it connected Wellington with Departure Bay. The company had simply grown too large for one person to handle the day-to-day management of both mining and shipping. It was corporate expansion and Robert’s widening interests that brought James to the Departure Bay office. Robert’s son-in-law John Bryden, who left an uncomfortable position as joint manager of the rival Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company in Nanaimo, replaced James at the Wellington mine. Meanwhile, the citizens of Nanaimo and Wellington realized that much of the progress in their communities was due to the Dunsmuirs, father and son, and, after the fashion of the day, provided “Jim” and Laura with a testimonial dinner and gifts in February 1881 at the time of his transfer, citing his considerate manner, concern for the safety of the miners, and gentlemanly behaviour.

During the next half decade, although production remained steady, the position of the company changed dramatically. It consolidated coal lands in the Comox valley to the north, and it acquired a charter and huge land grant for the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway, which it built in concert with California entrepreneurs. Robert bought out the original partners in the Wellington mine and renamed the company R. Dunsmuir and Sons in 1883. With the second son, Alexander, in charge of the San Francisco sales office, and with Robert a provincial cabinet minister from 1887, more and more of the management fell upon James. From this time he became the real force behind corporate expansion and rising profits.

His priority was the opening of the excellent coalfield in the Comox area, which his father had steadfastly refused to develop. Finally, in 1887, Robert succumbed to his son’s persistent requests. From the new diamond drill for the test holes to the mechanical coal cutters which did the work of ten miners, this Union mine at what would become Cumberland met the latest standards of efficiency and good management. Working closely with John Bryden, James put in the first shaft, constructed a camp, and built a rail link to tidewater at Union Bay in a matter of months. By 1890, its third year of operation, the mine produced 114,792 tons of coal, an amount it had taken the Wellington mine twice that time to reach. James Dunsmuir’s first solo project proved him as aggressive as his father had once been and just as capable

Meanwhile, in April 1889, Robert had suddenly died. Had the sons been expecting to assume total command of the business, their hopes were thwarted, since he had left all his shares and voting power to his wife. Frustrated and increasingly embittered, for the next 17 years James worked relentlessly to wrest control from his mother and sisters. The dispute was complicated by Alexander’s liaison with Mrs Josephine Wallace in California and his increasing alcoholism, which led to his death in 1900, and by conflicting legal documents and wills. It was more than a struggle of generations: it was also about keeping wealth within the family and a matriarch’s determination to maintain the rank of her eight daughters. In 1903 James had the humiliation of being sued by his mother for control of the San Francisco sales office, and spending three days on the witness-stand as the Dunsmuirs’ family affairs became headline news. Yet, through it all, he persevered, and he succeeded. He was confirmed as the sole owner of the Wellington colliery, the Alexandra colliery in the South Wellington district, and the San Francisco office and as the major shareholder of the Union Colliery of British Columbia and the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway. With his purchase of the California shareholders’ interests in the railway and the Union mines in October 1902, he finished bringing the empire entirely into his own hands, something his father had never been able to achieve.

Dunsmuir’s business endeavours around the turn of the century also involved improvement of existing enterprises and expansion in both mining and transportation. Although Alexander was president of the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway between his father’s death and his own demise, it was primarily James who oversaw the operation. The most important innovation was a ferry-barge service from Ladysmith Harbour on Vancouver Island to Vancouver that in 1900 connected the line to the North American railway network. Significantly, from the following year the Esquimalt and Nanaimo began to experience profits for the first time. At Union Bay in the mid 1890s, Union Colliery constructed a series of ten coke ovens to process the previously discarded coal dust. Dunsmuir also produced fire clay for brick making, initially used only for construction at the Union mine but later sold. Meanwhile, production at the mine continued to expand. It was, however, in the Nanaimo region that the most significant new development occurred.

Even before the sons persuaded their mother to sell them the Wellington and Alexandra collieries in late 1899, they had decided to close the flagship of the company, the Wellington mine that had provided Robert with his millions. With its riches depleted, the liquidation would be brisk. Their decision was eased by the discovery and acquisition of lands having a continuation of the Wellington seam southwest of Nanaimo. There, at Extension, James opened a new mine with a rail connection to the town-site and shipping centre at Oyster Harbour, which he renamed Ladysmith in honour of a British victory in the South African War. By early 1900 Wellington was a ghost town and the shipping facilities at Departure Bay were abandoned. Continued success came only to coalmine entrepreneurs who acquired new resources and developed them. With the opening of operations at Cumberland and Extension, Dunsmuir had solidified his corporate power, secured continuing prestige and wealth, and maintained the family practice of making the most of opportunities.

Dunsmuir reached the pinnacle of Vancouver Island society with a move from Nanaimo to Victoria in the early 1890s and the construction of a new residence, Burleith, a show-piece complete with electricity and every modern convenience. In an era of stone-turreted mansions and flamboyant lifestyles, croquet tourneys (at which James excelled), private yachts, and a recognition of growing leisure as a benchmark of success, the Dunsmuirs set a standard few could match. From the inaugural ball at Burleith, at which 300 guests waltzed among the potted palms and flowers, to the strawberry socials and the recitals on the Steinway grand parlour-piano, the Dunsmuirs’ style matched their status as British Columbia’s richest family.

Given the tradition of public service he inherited from his father, and his status in British Columbia society, James’s entry into the political realm was a natural progression. Beginning with his election as mla for Comox in 1898, he would rise to premier in 1900 and lieutenant governor in 1906. These were turbulent times in British Columbia politics and the Vancouver Daily Province noted correctly that “his experiences and training in life . . . unsuited him for the experiences and compromises which a political career involved.” Little more than an interim premier as the province groped its way toward party government, Dunsmuir nevertheless had some influence in the position, which he held between 15 June 1900 and 21 Nov. 1902. His three and one-half years as British Columbia’s lieutenant governor, from 11 May 1906 to 11 Dec. 1909, were noteworthy for the active social life which centred on Cary Castle, the official residence.

Although critics at the time and some historians have accused him of entering politics to serve his own interests, including the forestalling of efforts to curtail employment of Asian labour, Dunsmuir sometimes acted against what appeared to be his personal advantage. For example, in 1902 his government brought in a redistribution bill that shifted the political balance in the assembly from Vancouver Island to Vancouver and the Kootenay mining district in order to reflect the population growth in those regions. Two seats on the island disappeared, one at Esquimalt where Dunsmuir would soon build his new house, and his own seat of South Nanaimo. The introduction of a small tax per ton on coal and coke, taxes on the gross output of mines, and a graduated income tax prompted the Nelson Daily Miner to admit that “those terrible Dunsmuirs improve on nearer acquaintance,” while the Rossland Record, also in the Kootenays, cited these financial levies as evidence of “the Premier’s ability to set public duty above private interest.” Meanwhile, the British Columbia Mining Association rallied against the taxes and measures brought in by previous governments, including the Inspection of Metalliferous Mines Act and the Master and Servant Act, which it deemed pro-labour. It complained that such legislation was driving venture capital from the province.

On the question of Asian immigration, Dunsmuir’s record is more complex. He was the province’s largest employer of Asian labour, and during the election campaign of 1900 had promised to remove the Chinese workers from his operations in the Nanaimo area. As this removal began to happen, the Nanaimo Herald announced that it would “suspend our invectives until we have evidence that he has fooled the people.” Dunsmuir seems to have appreciated the severity of public discontent on the issue. He warned Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier in 1900 that agitation would grow to “undesirable prominence” unless the federal government increased the poll tax on Chinese immigrants. Later, on the grounds that it encroached on federal jurisdiction, Dunsmuir as lieutenant governor reserved provincial legislation that attempted to restrict Asian immigration. Yet the signals are mixed. As an employer, he had fought in court against government restrictions on the hiring of Asians, eventually winning an opinion in his favour from the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council [see John Bryden], but he deducted between 50 cents and one dollar per month from “each Chinaman working in and around the mines . . . to cover part of the costs of carrying the Chinese case” to this highest court of appeal. Secretly, while lieutenant governor he negotiated with the Canadian Nippon Supply Company for the importation of up to 500 more Japanese workers, an order the company was unable to fill. It would appear that business considerations generally triumphed with Dunsmuir when there were choices to be made.

The remaining focus of the Dunsmuir government involved railways and a “pack of charter mongers” who pushed 17 bills through the house with the aid of private members. Dunsmuir took no direct part, but he replaced land grants in support of construction with cash subsidies to be paid only when a line had been completed and approved. He also revived George Anthony Walkem*’s fight with Ottawa over the terms of confederation. Faced with increasing deficits, he emphasized that the eastern provinces had come into confederation with an infrastructure of public works already in place and requested that his province receive compensation.

During the decade of his political career James began to divest himself of his corporate empire. In 1905 he sold the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and its land grant to the Canadian Pacific Railway for $2,300,000, a deal through which he became a director of the CPR. Not surprisingly, he retained the lands necessary to mine and transport coal and the rights to coal under the entire grant, which covered a third of the island. In 1910 he sold his mining empire to the Canadian Northern Railway interests for $11,000,000. Calling the newly constituted subsidiary Canadian Collieries (Dunsmuir) Limited was an unfortunate choice because it would keep the Dunsmuir name prominently displayed on Vancouver Island for radical labour to despise, even though the family owned no shares and played no part in management.

“There is no individual in British Columbia respecting whom public opinion is so hopelessly divided as over Honourable James Dunsmuir. . . . If short-range critics and sycophantic friends in his entourage are now at hopeless variance, what likelihood is there of the masses forming a correct view of him?” This conundrum had been posed by the Daily Province in 1908 and it remains unanswered today. Both contemporaries and later interpreters have either eulogized him or pictured him as a tyrannical icon of bloated capitalism, depending on their view of the world. In the tradition inherited from his father, James Dunsmuir saw workers as part of a family watched over by a stern patriarch who had their best interests at heart. Even as late as the 1970s local residents remembered “personal acts of kindness he rendered to a crippled miner or his dislike of pomp or . . . his practice of talking to the men on a first name basis.” It was in this spirit that dozens of Wellington miners had pulled the hearse containing Robert Dunsmuir’s body through the streets of Victoria in 1889. Although more modern workers reject such personalized relations as dependence, at that time, for many, deference was natural. Often, as was the case with both Robert and James, the workers elected their employers to political office. To employers in such a context, strikes become acts of ingratitude or even insubordination against a wise parent.

By the time James had begun to assume control of the company in the 1880s, some workers had rejected condescending benevolence and were insisting upon independence and dignity. Coalmines were dirty, noisy, dark, and dangerous places, and the gaseous Vancouver Island mines were among the most hazardous in the world. As settings for risky work done by unusually independent-minded people, they bred or attracted some of the most militant labour. Writing in 1890, a Wellington miner informed the Dunsmuirs “that we are not slaves, but a free people, and, as such, we cannot allow ourselves to be tyrannized over.” Although not all workers agreed, the most radical, infused with a Marxism that had made them aware of their exploitation and provided them with the dream of power, began to see capitalists as evil. The owner-manager of the largest firm in British Columbia and the province’s richest man, Dunsmuir easily became a target. Adamantly opposed to unions of any kind and ever ready to fire their organizers, he did little to quell the rising tide of discontent. In this respect he was in step with other employers, who in the United States chose a belligerent stance and in Vancouver in 1903 formed an employers’ association that advocated firings, blacklists, and employment of strikebreakers.

The Dunsmuirs, father and son, used all these tactics and also, like many of their Canadian counterparts, easily persuaded the provincial government to send the militia to keep the peace while strikebreakers continued to mine coal. Central to every labour dispute in the Dunsmuir empire was the demand for recognition of a union, but no Dunsmuir ever capitulated. There were two major strikes during James Dunsmuir’s management, the first between 19 May 1890 and November 1891 and the second from 11 March to 4 July 1903. In the first dispute a wage roll-back in depressed market conditions and the eight-hour day movement provided the additional issues, while in 1903 the firing of union organizers and the demand for union recognition overshadowed all other factors. In the first instance the provincial government cooperated by sending in the militia. In the second confrontation it was the federal government which established a royal commission to investigate the alarming number of industrial disputes in British Columbia. As in all previous strikes against the Dunsmuirs, labour solidarity eroded as the miners, many of whom had been evicted from company-owned houses, drifted back to work with the realization that there would be no concessions from their employer. Although focused on Dunsmuir, the hatred of the most militant workers also encompassed the strikebreakers, both those imported during the strike and the employees who broke rank and returned to work. The basic issue for both sides was power. For Dunsmuir to have agreed to union recognition and other demands during a strike would have been a sign of personal weakness. Yet he did reduce the hours of employment to eight and a half after the 1890–91 strike and, by 1900, the Extension miners had their eight-hour day. Such decisions were not to be concessions to militant labour in a strike setting, but a gift from a paternalistic manager who was aware of the international trends. Similarly, Dunsmuir imposed labour contracts which established wages and working conditions for set periods.

As the most controversial individual in British Columbia, Dunsmuir, like his father, reacted quickly to all those who crossed him. There is no evidence, however, that he sacrificed human life deliberately or paid significantly lower wages than his competitors. Given the general shortage of labour on the coast, to do so would have been impossible. Even the much-maligned company houses and stores began to disappear while he managed the firm. His opposition to labour unions was a facet of his opposition to anyone who, in his opinion, unfairly impeded his freedom as a capitalist. His battle with the provincial government against restrictions on the employment of Chinese labour reflected the same attitude. And until 1904 he fought against the rights of those settlers on the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway lands who had established themselves before Dunsmuir ownership. In 1897 he successfully sued the province for $12,412 because it had decided against using Dunsmuir quarry stone in the new legislative buildings. Two years earlier he had secured a charter for the Comox and Cape Scott Railway on northern Vancouver Island for no other reason than to forestall the ambitions of other individuals.

Throughout the often vicious public criticism, Dunsmuir made no attempt to justify or defend himself. Practical, honest, reliable, and unassuming, he had a certain brusqueness of manner which conveyed an impression of cold haughtiness. Parsimonious throughout his life, he resisted what he believed to be excessive charges by shippers, merchants, doctors, and hydro suppliers. Yet he gave generously to churches, orphanages, hospitals, and agricultural exhibitions, and from June 1900 donated $25 per month to the Extension Mine Accident Fund. His tendency to self-depreciation has contributed to negative assessments of his business career. In 1903, during the family dispute, he said on the witness-stand that he had usually deferred to his brother in business decisions. Those who have labelled him as simple, unimaginative, and unambitious have based their conclusions on such personal assessments rather than on the progress of the company during the period in which he was in control, when Alexander’s health and business competence were quickly fading.

Corporate records leave no doubt that James ran the company on a daily basis, even when he was premier. A comparison of these records for the three years before James assumed control with those for 1910, the year of the sale of his mining interests to the Canadian Northern, provides conclusive evidence of his accomplishments as an entrepreneur. Production rose from a level of 215,021 tons to 898,908 tons. The average workforce grew from 575 to 2,519. Sales increased from 215,127 tons of coal to 706,890 tons of coal and 8,327 tons of coke, which was not being manufactured in the earlier period. In the five years before the Wellington collieries were sold, profits from them were $3,368,845. It is obvious that the value of the company increased dramatically under Dunsmuir’s stewardship and that he substantially enlarged the family fortune.

It is difficult to understand why, at age 61, Dunsmuir retired from the corporate world. Perhaps he was wearying of confrontation with increasingly militant workers, or perhaps he was discouraged by the growing popularity of oil in the United States, which was already seriously depleting the firm’s key market. More probably, he sold up at the most opportune time to maximize his profit. He may also have been responding to the increasing value placed on leisure and to the general economic decline of Vancouver Island, or, like his father who withdrew from active corporate participation at the same age, he may simply have lost interest in furthering the empire. Perhaps several of these factors were at work.

Retiring to the life of an English gentleman at Hatley Park, in Esquimalt, he devoted his remaining years to fishing and estate management. An Edwardian mansion of 50 rooms on 640 acres, complete with modern dairy and slaughterhouse, Hatley Park was complemented with the 218-foot steel yacht Dolaura, which had a dining room that could seat 24, and a fishing lodge on the Cowichan River. These possessions were not, however, a flamboyant display of wealth. Whereas his father had built a centrally located castle which dominated the Victoria skyline, James withdrew behind fences on a large, relatively remote estate. Such a retreat was not unusual in this period, nor was his obsession with hunting and fishing. Describing himself as “a common working man,” like other managers of his generation Dunsmuir compensated for his removal from the physical labour and skill of the workplace with an attempt to find manliness in sports such as hunting and fishing. He also took up golf with a focused determination to excel.

The compensation, however, does not appear to have been sufficient. Increasingly isolated and lonely, he experienced little happiness in his final years. With his eldest son devoting his life to globe-trotting in an alcoholic stupor, a second son a victim of the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, and his daughters, who generally had married into British-based, upper class, military families, leading frivolous lives, there was to be no worthy third generation of Canadian Dunsmuirs. The lifestyle and Old World pretensions so carefully cultivated by the family disintegrated before his eyes. After his death at his fishing lodge in 1920, the children squandered the fortune in one generation.

For a few years James Dunsmuir had been the richest and allegedly the most influential man in British Columbia, with the authority that derives from corporate power. He did not create singlehanded the labour climate, but he did contribute to its strident militancy with his strong-arm tactics. Similarly, although he did not make the racist attitudes in the province, his large-scale employment of Asians, whom he often used as strikebreakers, intensified the debate. Yet, as a successful Vancouver Island entrepreneur who dominated the local economy, he also created communities and provided living wages to thousands. His retirement coincided with the decline of the island’s economy as the focus shifted to the lower mainland. Admittedly he had exercised his power during auspicious times, but he was a talented businessman whose wealth and influence exceeded that of his father.

BCARS, Add.

Cite This Article

Clarence Karr, “DUNSMUIR, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dunsmuir_james_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dunsmuir_james_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Clarence Karr |

| Title of Article: | DUNSMUIR, JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |