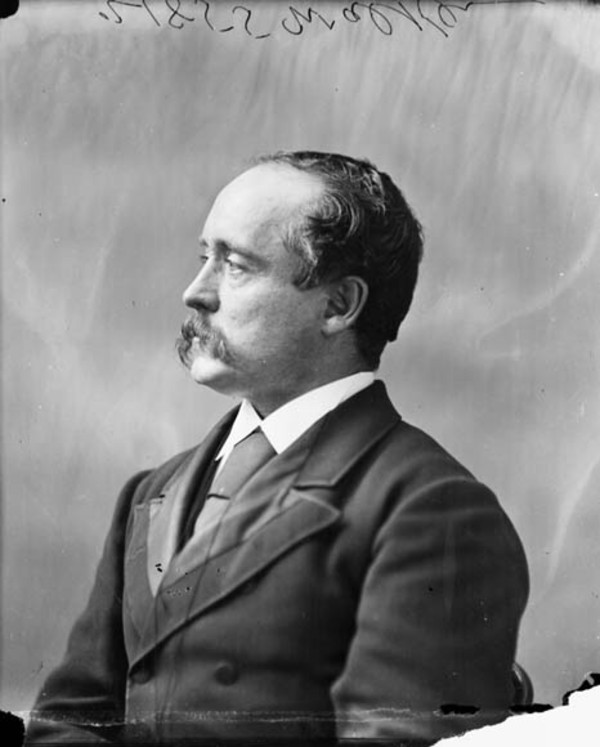

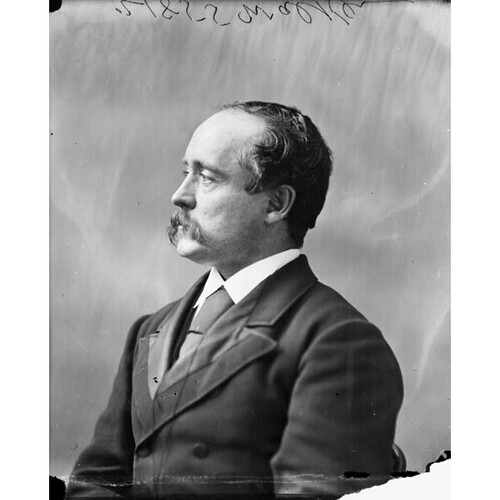

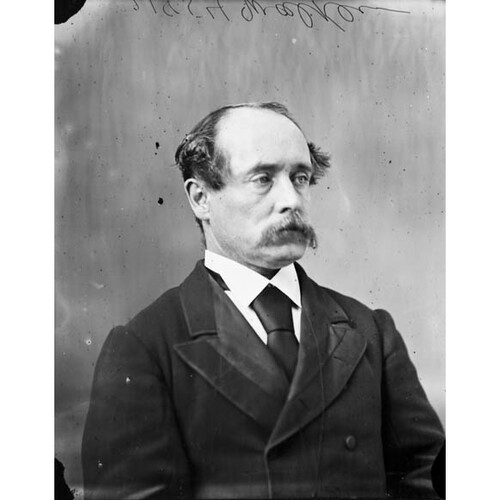

WALKEM, GEORGE ANTHONY, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 15 Nov. 1834 in Newry (Northern Ireland), son of Charles Walkem and Mary Ann Boomer; m. 30 Dec. 1879 Sophia Edith Rhodes in Victoria, and they had one daughter; d. there 13 Jan. 1908.

George Anthony Walkem was one of ten children born into a family whose roots were in southwest England. They emigrated to Canada in 1847, where the senior Walkem gained employment with the Royal Engineers and the young George, after completing his schooling, went to McGill College in Montreal. He read law with John Rose*, and was called to the bars of Lower and Upper Canada in 1858 and 1861 respectively. During the Cariboo gold-rush of 1862 he moved to British Columbia, and in September applied to judge Matthew Baillie Begbie* for admission to the bar.

Unfortunately Begbie preferred “duly educated” – that is, British-trained – barristers. He refused to call Walkem, who therefore decided to advise plaintiffs informally. When petitioned on Walkem’s behalf, Governor James Douglas* sought the opinion of the secretary of state for the colonies, who favoured admission, and in June 1863 the governor proclaimed the Legal Professions Act, permitting “colonial” lawyers to plead in court. Begbie finally admitted Walkem to the bar five months later, apparently under pressure from Douglas.

Walkem conducted a prosperous law practice in the Cariboo district. Throughout his career he was popular among the miners, and he is said to have drafted a code of mineral law “for their guidance.” Many became his clients, but he rubbed Begbie the wrong way on occasion when he represented them in court. However, the judge’s decisions about mining in the Cariboo were controversial, and Walkem’s legal reputation appears not to have suffered from such encounters.

In 1864 Walkem was elected to the Legislative Council of British Columbia as the representative for Cariboo East and Quesnel Forks District. In this capacity he advocated union with the colony of Vancouver Island and later joined Amor De Cosmos* in the Confederation League. He was also an early supporter of decimal currency. When Vancouver Island and British Columbia united in 1866 Walkem maintained his seat on the expanded legislative council, but from 1868 to 1870 he sat on it as an appointed justice of the peace. In the debate of March 1870 on confederation with Canada he took a rather minor part, urging a cautious but firm approach to negotiations over the proposed transcontinental railway. He opposed the introduction of responsible government into British Columbia, debated at the same time, on the grounds that it was likely to exacerbate tensions between the island and the mainland. He was not a member of the last session of the council (1870–71), which by then had a majority of elected members.

Following confederation, on 16 Nov. 1871 Walkem was returned for Cariboo to the first provincial legislative assembly, and he became chief commissioner of lands and works in Premier John Foster McCreight*’s short-lived administration. On 23 Dec. 1872 De Cosmos, who was a member of parliament as well as of the assembly, replaced McCreight and formed a government of men who, prior to 1871, had been identified with reform and confederation. With only one interruption, these men, not the more conservative elements who before that date had run the colony, held power until 1883. Although Walkem had a somewhat jaundiced view of De Cosmos, whom he once described as having “all the eccentricities of a comet without any of its brilliance,” he accepted the post of attorney general. As a result he was in charge during the premier’s many absences in Ottawa, and when De Cosmos resigned in February 1874, Lieutenant Governor Joseph William Trutch asked Walkem to replace him. Thus Walkem was both premier and attorney general for most of British Columbia’s first decade as a province.

On taking office as premier he was faced with the Texada scandal – allegations that he and other members of the De Cosmos government stood to profit from public development of newly discovered iron ore on Texada Island. A royal commission requested first by John Robson* and then by Walkem himself was established to investigate. Composed of the province’s three Supreme Court judges and chaired by Begbie, it concluded later in the year that there was insufficient evidence to charge anyone with an attempt to prejudice the public interest. Although a whiff of scandal remained, Walkem had insisted “I did not take silver for iron,” and must have felt vindicated.

In the politically excited atmosphere of the time, however, his opponents continued to see him as a man not to be trusted. To Mr Justice Henry Pering Pellew Crease he was “the little Trickster.” And even Sir John A. Macdonald*, who was an ally, once said he was “inclined to sharp practice.” More charitably, he may be called a pragmatist operating in the context of a volatile electorate: if, as some people believed, he too easily sacrificed principle to politics, he can perhaps be considered British Columbia’s first modern politician. Certainly he was a survivor, although even his notable abilities sometimes failed him, as the dispute over the transcontinental railway reveals.

When British Columbia entered confederation, it had been promised that construction of the railway would be started within two years and finished within ten. Delays ensued, however, and in March 1874 James David Edgar*, the dominion government’s envoy, arrived to propose certain changes to the railway clause in the province’s terms of union. Walkem refused to give them formal consideration until Edgar’s authority had been confirmed. His action reflected not only his disdain for Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie* but also his own political situation. He had yet to face an election as premier, and in February the legislature had resolved that no changes to the railway could be made without the consent of the people. Moreover the proposed changes were particularly likely to disappoint Walkem’s own constituents in Cariboo because they involved substituting the extension of the line as far as Esquimalt for timely completion of the main portion. He therefore opted to go to London to plead the province’s case before the secretary of state for the colonies, Lord Carnarvon. Carnarvon suggested himself as an arbitrator, and Walkem and Mackenzie felt obliged to accept. In the result the terms of union were altered without an election in British Columbia. Walkem’s star fell even further when Mackenzie’s attempt to comply with the Carnarvon Terms failed. Although they had taken months to secure and were not really so very different from Edgar’s, the Senate blocked them in 1875.

Walkem therefore faced the electors in the autumn of 1875 amid charges that he had weakened the terms of union without consulting the people and had done nothing to start railway construction. He was also accused of plunging the province into debt by engaging in public works that it could ill afford. Nevertheless, his government was returned, albeit with a reduced majority. Discontent over the railway persisted, and on 21 Jan. 1876 the legislature unanimously resolved to petition the queen for the redress of the province’s grievances.

Other issues occupied the attention of Walkem’s administration as well. In addition to passing the province’s first explicitly racist statute, which denied Chinese and native people the vote, his government took a comparatively hard line on the size of Indian reserves that were to be set aside by the province pursuant to the terms of union. Lieutenant Governor Trutch argued that there was no Indian title in British Columbia and that federal policy on reserves, which promised 80 acres per family, was unsuitable west of the Rockies. According to him, 10 were sufficient. Although Walkem soon modified this stance somewhat, he and Trutch did not want documentation on the grievances of native people made public, and he may have stalled settlement of the Indian land question to retaliate against the Mackenzie government for its position on the railway.

In the end it was finances that sealed Walkem’s fate as premier. When allegations were made that funds the government had borrowed from the dominion would be charged against the annual subsidy to the province, Thomas Basil Humphreys* moved a no-confidence motion. Walkem lost by 13 votes to 11 and resigned. His administration was replaced on 1 Feb. 1876 by a new one headed by Andrew Charles Elliott*, who discovered that the Bank of British Columbia had refused to loan the government any more money.

During Elliott’s term Walkem remained influential. As leader of the opposition he enjoyed a considerable degree of control over public affairs, partly because Elliott’s coalition was even shakier than his had been, and partly because he was a skilled politician. And in 1877, after Elliott called out the militia during a strike at the Wellington coalmine [see Robert Dunsmuir*], Walkem attracted attention by defending the arrested miners. This move added to his reputation as a friend of the working man, opposed to both legal repression and cheap Chinese labour. (It also did not hurt that all but one of his clients were acquitted.) Accordingly, an early initiative of Walkem’s second administration, formed on 25 June 1878, was the insertion of a “no Chinese labour” clause in all contracts for public works. The government also secured passage of the Chinese Tax Act of 1878 which, until it was struck down as unconstitutional by the provincial supreme court later that year, imposed a discriminatory tax on all Chinese [see John Hamilton Gray*].

Walkem’s new government had a comfortable majority, although in a sense there is no such thing in a system without political parties. It had been returned in an election precipitated by Elliott’s defeat in the house over a redistribution bill, and it managed to stay in office for another four and a half years. “Fight Ottawa” and “Secession” had been Walkem’s campaign slogans, and so he took up where he had left off on the railway. A resolution he introduced in the legislature on 29 Aug. 1878 called upon the province to secede if construction was not commenced by May 1879; it passed 14 to 9 but went by the board when the more sympathetic Macdonald government was re-elected in Ottawa. Although this political event resolved the main issue, Walkem continued to fight the dominion on the questions of the Vancouver Island extension, which was now being downgraded to a secondary line, and the lands that the province had been obliged to grant Ottawa as a subsidy for the railway. Frustrated by the lack of progress, the British Columbia government was dragging its feet over the transfer of title. Caught between the different priorities of Victoria and the mainland, Walkem refused for months even to meet with Trutch, who was now Ottawa’s agent for resolving outstanding railway issues. On 21 March 1881 the legislature made another demand for justice and De Cosmos was sent to England to launch a further appeal. Concerns about British Columbia’s strategic importance to the empire prompted London to urge more concessions on the dominion government. But Vancouver Island remained unhappy, and Walkem’s relations with Macdonald, who described his actions on one occasion as “equally foolish and dishonest,” deteriorated. The worry grew, especially on the mainland, that the incessant wrangling might lead to the cancellation of the railway altogether.

Walkem faced serious difficulties in other directions. He survived an 1880 lawsuit alleging that his acceptance of fees for dominion legal work disentitled him to sit in the assembly, but his failure to keep his election promise to pass a redistribution law lost him a great deal of support. And although he had earlier opposed tolls on the Cariboo Road, he now increased them. Moreover he became entangled in a feud with British Columbia’s judges, who maintained that the provincial supreme court was immune from his attempts to regulate procedure and to require them to reside in their judicial districts [see Crease]. The new Supreme Court of Canada overruled them on this point in 1883, but in the meantime Walkem’s public reputation, and their own, suffered considerably. Worse still, the cost of the Esquimalt graving dock was escalating beyond the ability of the province to pay. In the terms of union the dominion government had agreed to loan British Columbia money to finance its construction, but over the years the contributions of Ottawa and then London, which had agreed to make a conditional grant of funds, had been the subject of continuing negotiations. The graving dock was also a sore point in relations between the island and the mainland. Mainlanders had long resented the island’s dominance and saw the difficulties over the dock as a threat to the completion of the railway. Islanders believed that the railway would primarily benefit the mainland and that they needed the dock so that Victoria’s economy would also prosper. Unfortunately for Walkem, soon after he had unwisely promised that the project would cost not a cent more, it turned out that his government had miscalculated. When expenses continued to soar, his majority in the legislature plunged, and his political skills were taxed to the limit. Although in April 1882 he survived a motion of no-confidence, the vote was extremely close, and in July the government suffered a resounding defeat at the polls.

By then Walkem was no longer premier. He had been replaced by Robert Beaven* because, on 23 May, Macdonald had appointed him to the provincial supreme court to fill the vacancy left by the late Alexander Rocke Robertson*. Macdonald’s decision is said to have been prompted by Trutch’s assertion that the task of resolving railway issues would be much easier if Walkem were on the bench instead of in the premier’s office. Alternatively it has been suggested that Macdonald was returning a favour since Walkem may have played a role in getting him the House of Commons seat for Victoria after his personal defeat in Kingston in the 1878 election.

A few days before Walkem stepped down on 6 June to take up his judicial position, the Victoria Daily Colonist, which was not without its own axes to grind, described the dominion as having “rid the [province] of an incubus of which in the space of a few weeks it would have rid itself.” While it hoped to be proved wrong, the newspaper said that the appointment “seriously affected” the “status” of the court. By its own admission, it was indeed wrong. When Walkem died 26 years later, it suggested that the difficult problems facing government during British Columbia’s “critical” early years as a province had been solved mainly through his “perseverance and statecraft.” By then Walkem had been retired for four years, but it was largely his record as a judge, as well as the passage of time and the cooling of political passions, that prompted this change of heart. Perhaps a growing recognition that British Columbia’s relations with Ottawa were inherently difficult also played a part.

Although his judicial career had begun on a sour note – Walkem, despite his own legislation, declined to leave Victoria and reside in his judicial district-he had soon established himself as an able member of the court. He was pleasant, and in the Cariboo his obvious affection for the people and his knowledge of mining law made him especially appreciated, even if he occasionally waxed excessively nostalgic when addressing grand juries. The animosities of the past were gradually forgiven, if not forgotten, and Walkem and his judicial brethren also enjoyed an amicable relationship. For example, in 1887 he and justices Crease and Montague William Tyrwhitt-Drake established new rules of court to replace the rules that Walkem, as premier, had drafted six years earlier. When he retired from the bench on 2 Oct. 1903, the Vancouver Daily Province spoke of his “lasting reputation as an able jurist” and concluded that he would be “greatly missed.” Another newspaper wrote that he was “one of the brightest ornaments of British Columbia’s judiciary.” Perhaps these were simply the usual encomiums, but Walkem the judge clearly evoked much more respect and affection than Walkem the politician.

[Walkem’s name is occasionally given as George Anthony Boomer Walkem, but his will, in BCARS, GR 1052, box 52, file 7695, and his probate file, GR 1304, file 1908/3229, give simply George Anthony Walkem. It may be that Walkem’s opponents sometimes used Boomer in his name to make fun of his politics. h.f.]

BCARS, Add. mss 54; Add. mss 55. NA, MG 26, A, 294, 385, 574; F, 5; RG 13, A5, 2038, file 3821/2. British Columbian, February 1882. Cariboo Sentinel (Barkerville, B.C.), July 1867. Daily Colonist (Victoria), June 1880; November 1881; February, June 1882. Vancouver Daily Province, October 1903. Victoria Daily Standard, February 1882. Victoria Weekly Standard, January 1882.

Barnard v. Walkem (1880), British Columbia Reports (Victoria), 1 (1867–89), pt.1: 120–46. B.C., Papers connected with the Indian land question, 1850–1875 (Victoria, 1875; repr. 1987); Dept. of the Provincial Secretary, Report on the subject of the mission of the Honorable Mr. Walkem, special agent and delegate to the province of British Columbia to England with regard to the non fulfilment by Canada of the railway clause, of the terms of union (Victoria, 1875); Royal commission for instituting enquiries into the acquisition of Texada Island, Papers relating to the appointment & proceedings (Victoria, 1874). B.C. Executive Council appointments (Bennett and Verspoor). British Columbia Gazette (Victoria), 1880–82. Electoral hist. of B.C. Hamar Foster, “How not to draft legislation: Indian land claims, government intransigence and how Premier Walkem nearly sold the farm in 1874,” Advocate (Vancouver), 46 (1988): 411–20; “The Kamloops outlaws and commissions of assize in nineteenth-century British Columbia,” Essays in Canadian law (Flaherty et al.), 2: 308–64; “The struggle for the Supreme Court: law and politics in British Columbia, 1871–1885,” Law & justice in a new land: essays in western Canadian legal history, ed. L. A. Knafla (Toronto, 1986), 167–213. G.B., Parl., Command paper, 1875, 52, [C.1217], Correspondence respecting the Canadian Pacific Railway Act so far as regards British Columbia. Higgins v. Walkem (1889), SCR, 17: 225–34. In the Supreme Court of British Columbia . . . between the Honorable George Anthony Walkem, plaintiff, and David William Higgins, defendant . . . (Victoria, 1887). In the Supreme Court of Canada . . . between David William Higgins . . . and the Honorable George Anthony Walkem . . . (Victoria, 1887). S. W. Jackman, Portraits of the premiers: an informal history of British Columbia (Sidney, B.C., 1969). Journals of colonial legislatures of Vancouver Island and B.C. (Hendrickson), 5: 444–575. Kerr, Biog. dict. of British Columbians. J. P. S. McLaren, “The early British Columbia Supreme Court and the ‘Chinese question’: echoes of the rule of law,” Manitoba Law Journal (Winnipeg), 20 (1991): 107–47. D. P. Marshall, “Mapping the political world of British Columbia, 1871–1883”

Cite This Article

Hamar Foster, “WALKEM, GEORGE ANTHONY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walkem_george_anthony_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walkem_george_anthony_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hamar Foster |

| Title of Article: | WALKEM, GEORGE ANTHONY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |