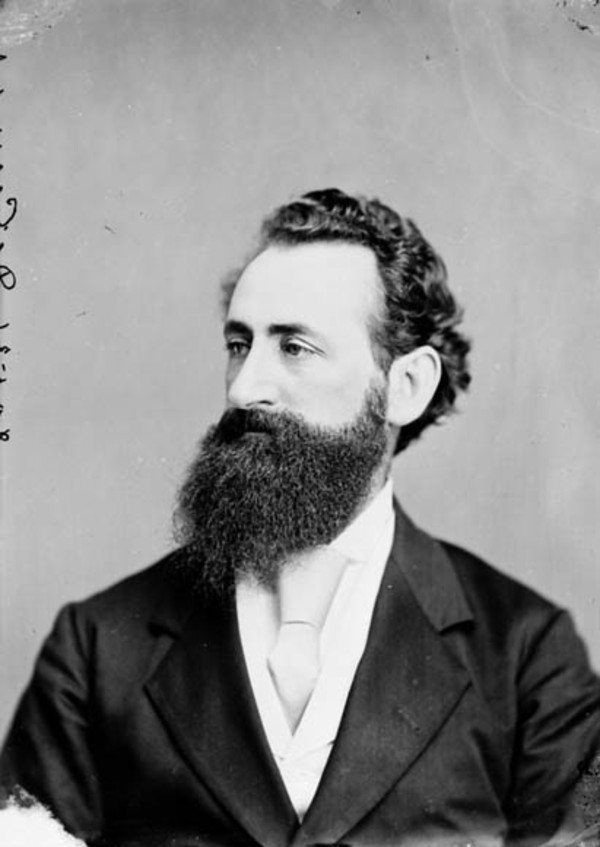

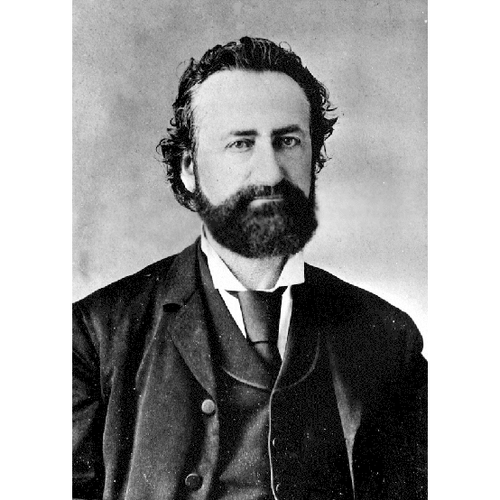

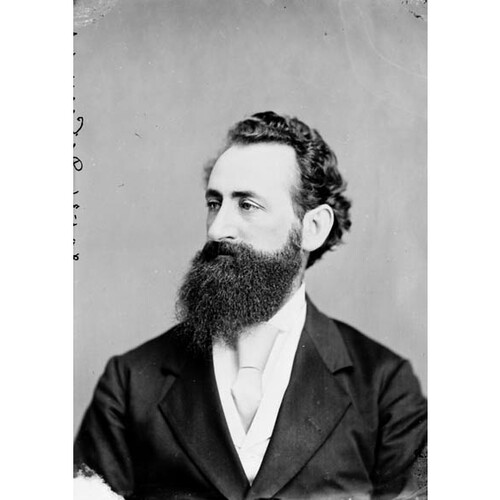

DE COSMOS, AMOR (named at birth William Alexander Smith), businessman, photographer, journalist, and politician; b. 20 Aug. 1825 in Windsor, N.S., son of Jesse Smith and Charlotte Esther Weems (Wemyss); d. unmarried 4 July 1897 in Victoria, B.C.

Born into a family who had come to Nova Scotia from the American colonies after the American Revolutionary War, William Alexander Smith was educated first at a private school and later at King’s College School in Windsor. About 1840 his family, which at that time included two boys and four girls, moved to Halifax where he became a clerk in the wholesale and retail grocery house of William and Charles Whitham. During this period he also attended night classes at the grammar school run by John Sparrow Thompson* and was a member of the Dalhousie College debating club.

In 1852 Smith left Halifax for the gold-fields of California. He journeyed from New York to St Louis, Mo., where he joined a party intending to travel overland to the west coast. Indian troubles and other delays forced the group to winter at Salt Lake City, Utah. In the spring he left the party behind and, going on alone at some risk to himself, reached Placerville, Calif., in June 1853.

Once in the gold-fields, Smith began to photograph miners posing on their claims, using camera equipment brought with him across the plains. Since he was one of the first to establish this kind of business there, the venture proved “very profitable.” In 1854 his elder brother Charles McKeivers Smith, who had worked for some years in Halifax as a builder, joined him. The brothers settled at Oroville, and William engaged in “mining speculations and businesses of other kinds.” The same year he had his name legally changed by the California legislature to Amor De Cosmos, an unusual name, he admitted to jeering legislators, but one that symbolized “what I love most, viz: Love of order, beauty, the world, the universe.” It certainly would be more remarked upon and remembered than plain Bill Smith. Although the California statute prints the name as “Amor de Cosmos” he signed with a capital “D” accompanied until about 1870 by a Greek epsilon, and thereafter with a small “e.”

In January 1858, just before the gold-rush to the Fraser River, Charles migrated north to the British colony of Vancouver Island, where he became a builder and contractor in the settlement that had mushroomed around the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Victoria. After a reconnaissance trip north in May, De Cosmos wound up his affairs in California and followed his brother in June. A few months after arriving in Victoria, he embarked on a career as a journalist and politician that for 24 years would keep him at the forefront of public affairs on Vancouver Island.

The British Colonist, which De Cosmos founded and edited until 1863, first appeared on 11 Dec. 1858. In the editorial for the first issue, he established his credentials as a “friend of reform.” The target of what George Woodcock* has called De Cosmos’s “open and fearless criticism” was the colonial administration of Governor James Douglas*, the subject of attacks by Vancouver Island settlers throughout the 1850s. Although Douglas had given up his position as chief factor of the HBC in 1858, his government continued to be made up of an élite of former company officers and his own family members and friends. Reinforced in the following years by a growing number of educated civil servants and “gentlemen” from England, this group, dubbed the “family-company compact” by De Cosmos in February 1859, continued to control the colony after Douglas’s departure until 1871. Its members distrusted representative institutions and believed in a hierarchical social order, to be maintained through government support for an established church, a landed gentry, and a private, denominational system of education.

De Cosmos drew on the heritage of British liberalism, and especially on the ideas of his Nova Scotia mentor, Joseph Howe*, to challenge the power and underlying assumptions of this élite. He hated social, economic, and political privilege, distrusted “monopolies” and “incorporated companies,” and saw in ordinary people an intelligence and dignity that deserved respect. At the core of De Cosmos’s critique was the belief that government should run “according to the well understood wishes of the people.” These wishes, in his view, included acceptance of free speech, free assembly, representative institutions, and responsible government on Vancouver Island. He was convinced that self-government by elected assemblies would be more responsive to the settlers’ interests and cheaper than the colonial régime. All British subjects, regardless of colour, from Vancouver Island to Nova Scotia, should enjoy the “inalienable rights and privileges which Englishmen inherit.” Yet, as a mid Victorian liberal, De Cosmos also believed that ownership of property and social stability were essential prerequisites for responsible citizenship. Thus, although he argued for a more liberal franchise in his editorials in the early 1860s, he opposed universal male suffrage: voters should pay taxes and be resident in the community.

The same mixture of liberal ideas and settlers’ interests that defined De Cosmos’s approach to political reform also shaped his economic views. Reflecting the spirit of the age, he celebrated railways, “men of action,” moral and material progress, growing population, and expanding trade. His belief in the private ownership of resources was unquestioning. He consistently promoted farming as the foundation of colonial prosperity yet foresaw that in British Columbia settlement must build on a more diverse base. With its fisheries “an exhaustless mine of wealth” and its forests “practically inexhaustible,” the coast region awaited only capital and labour to prosper. Hence his frustration with the influence of Governor Douglas and the HBC who he felt, somewhat erroneously, had retarded economic diversification and expansion.

De Cosmos’s faith in contemporary economic values found expression in his private business endeavours. Soon after arriving in Victoria he started to invest in real estate, including land at Fort Langley, and by 1897 he held title to 34 pieces of property in Victoria valued in total at $118,000. The fact that this real estate was “hopelessly involved with mortgages” exceeding $87,000 suggests the speculative character of his investments. In the 1860s he promoted a quartz mine, a sawmill, and a cattle farm on Vancouver Island, the last to be located on the Cowichan Indian reserve, and in the late 1880s a railway/ferry system from Victoria to Swartz Bay and the mainland, all unsuccessfully. In short, both in California and on Vancouver Island, De Cosmos behaved as did many entrepreneurs in settler societies, buying and selling property and promoting businesses.

More complex than his political and business philosophy were his views on free trade and the tariff, for here his liberalism confronted a strong sense that the northwest coast, while part of the British empire, had its own identity. Although he proclaimed in 1862 that this was an age of “free press, free trade, and freedom” and argued ten years later for reciprocity in natural resources with states and territories to the south, he was always something of an economic nationalist, increasingly so by the 1870s. From 1859 the Colonist advocated not laissez-faire economics but “protection to our own industry” and government aid to business, whether in the form of a “bounty” to fishermen, a subsidy for local steamship companies, or free access to land and timber for farmers and lumbermen. After British Columbia entered confederation in 1871, De Cosmos regularly favoured tariffs to support infant “manufactures and agriculture.” The “colony was young,” he argued in the House of Commons in May 1872, and “required nursing.” Gilbert Malcolm Sproat*, a contemporary and occasional adversary, described him as a “thoroughgoing protectionist.”

De Cosmos’s economic nationalism was motivated in part by his profound commitment to political independence for Britain’s North American colonies. Chagrined by an imperial policy that forced colonies like Vancouver Island to be “entirely self-supporting” and thus dependent on their “own exertions,” he suggested in 1861 that the colonies “cultivate a nationality of their own.” Such a nation would emerge from a federation of all British colonies in North America, a goal which he had already defined clearly in the Colonist’s first editorial and which would earn him the title “father of British Columbia’s entry into confederation.” In the years that followed he supported the construction of an intercolonial railway and the aims of the British North American Association, backed by Joseph Howe. Underlying De Cosmos’s political agenda was the goal of cheaper government and a stronger economy. From this policy emerged two of the great causes of his career: the union of Vancouver Island and British Columbia and British Columbia’s entry into confederation. The final stage in British North America’s political evolution was to be the creation of an independent state represented in the imperial parliament. For De Cosmos, the “manhood” and “self-respect” of British North Americans revolted at the very idea of remaining the political inferiors of England. In the confederation debates of March 1870 in the British Columbia legislature, and then in a June editorial of the Victoria Daily Standard (a paper he had founded that year and edited until 1872), he claimed the only alternative to federal union was the “separation of Canada from England, and the making of the former into another sovereign and independent American nationality.” “I was [born] a British colonist, but do not wish to die a tadpole British colonist,” he stated emphatically to the House of Commons in April 1882; “I do not wish to die without having the rights, privileges and immunities of the citizen of a nation.” He specified that, although immediate independence would be premature, Canada should be able to control its own foreign relations. The suggestion that Canada might have to separate from Britain to gain full nationhood contributed to his defeat in that year’s federal election.

Coexisting with De Cosmos’s nationalism was an intense localism, based on the conception of “nation” as a collection of regional communities. Thus, as the Victoria Daily Times noted in its obituary, from his earliest days as a journalist and throughout his political career he identified closely with the interests of Victoria, his “adopted city,” whose battles he fought “through thick and thin, in his papers and in the legislature and house of commons.” For example, during the confederation debates he argued for favourable terms, such as a protective tariff, to ensure Victoria’s place as “the chief commercial city of British Columbia, with all other parts of the Colony tributary to her. This is what Confederation on proper terms will do for us.” The two commitments were compatible because De Cosmos envisioned a highly decentralized country in which, he noted in his “tadpole British colonist” speech, “each Province should be an independent State” as “obtains on the American side.”

During his political career, which began slowly, De Cosmos would serve as elected representative for Victoria or the surrounding area in the Vancouver Island House of Assembly (1863–66), the British Columbia Legislative Council (1867–68 and 1870–71), the British Columbia Legislative Assembly (1871–74), and the House of Commons (1871–82). Although he would play important roles in the era after confederation, including a tenure of slightly more than a year as the second premier of the province (1872–74), De Cosmos made his largest contribution during the colonial period. He ran the first time in the general election of 1860 for the second Vancouver Island assembly but was defeated by George Hunter Cary*. He stood again in a by-election, where his adopted name became an issue and he was forced to run as “William Alexander Smith commonly known as Amor de Cosmos.” The failure of one voter to recite this formula correctly resulted in his defeat. His agenda for reform having been clearly outlined during five years of “strong and vigorous” writing in the Colonist, he finally embarked upon the second phase of his public career with a victory in the general election of July 1863. During the three-year term of the third assembly he sat as one of four members for Victoria City.

The leading political questions faced by the assembly at the time – union with the neighbouring colony of British Columbia and retrenchment in colonial expenditures – stemmed from the decline of the mainland gold-rushes. In spite of fresh flurries of excitement, including one in 1864 at Leech River on southern Vancouver Island, no discovery occurred comparable to the 1862 Cariboo rush. De Cosmos was a principal advocate of union with British Columbia and was prepared to give up Victoria’s free port status to achieve it. This position brought him into conflict with the commercial leaders on Wharf Street. By January 1865 the assembly, under De Cosmos’s leadership, had passed resolutions pledging that the house would ratify union with the mainland colony “under such constitution as Her Majesty’s Government may be pleased to grant” and calling for “the strictest economy . . . compatible with the efficiency of the public service.” To test public support for these resolutions De Cosmos and Charles Bedford Young, an opponent of the resolutions, resigned. In the subsequent by-election in February 1865, De Cosmos was re-elected and Young was defeated by De Cosmos’s running mate, Leonard McClure*, the new editor of the Colonist.

Until the expiry of its term in September 1866, the assembly was at an impasse with the governor and the Legislative Council over colonial expenditures. Assemblymen tried and failed to reduce the civil list to save money for development, but Governor Arthur Edward Kennedy* refused to pare down his establishment of officials. The rancorous relations between the governor and the assembly were reflected in the constitution adopted at the union of Vancouver Island and British Columbia that November. The Colonial Office decided to submerge Vancouver Island in British Columbia, abolishing the assembly and extending the jurisdiction of British Columbia’s appointed Legislative Council over the united colony. The assembly died with its members protesting the British government’s decision, which prevented it even from ratifying the union. Political opponents accused De Cosmos of not foreseeing that the 1865 resolutions could be used to end the assembly.

When the first session of the Legislative Council for the new colony opened in early 1867, De Cosmos was there as a “popular” member representing Victoria. (Popular members were appointed by the governor after a vote in the area to be represented. No governor failed to appoint the person thus chosen.) He introduced a motion asking Governor Frederick Seymour* to take steps to have British Columbia included “on fair and equitable terms” in the confederation then pending in eastern British North America. The council passed the motion unanimously and Seymour telegraphed the request to the Colonial Office. After the session ended, De Cosmos travelled to the Province of Canada seeking allies among Canadian politicians for his fight. He attended and spoke at the Reform convention held in late June 1867 in Toronto, where George Brown* led delegates in renewing opposition to John A. Macdonald and his supporters.

In the 1868 session of the Legislative Council De Cosmos was less successful. Governor Seymour’s opening speech dismissed his 1867 motion as “the expression of a disheartened community, longing for change of any kind,” and argued that nothing could be done until Rupert’s Land was handed over by the HBC to the new dominion. De Cosmos replied with a draft address to the queen outlining terms for union. This initiative was defeated by an amendment which, while reaffirming the “general principle” of union with Canada, claimed that the members lacked “sufficient information” to define terms. Moved by two government officials, the amendment was passed by a vote of 12 to 4. Among those who favoured it were John Sebastian Helmcken* and Joseph Despard Pemberton, the other popular members for the Victoria area; only Edward Stamp*, John Robson, and George Anthony Walkem* (the last two future premiers) supported De Cosmos’s resolution. The vote reflected the increasing opposition to confederation in Victoria, the largest centre in the colony and its commercial heart as well as its seat of government since the transfer of the capital of the united colony from New Westminster earlier in the year.

Defeated in the legislature, De Cosmos and his allies began a campaign for confederation throughout the colony. In May, they founded the Confederation League, of which Robert Beaven*, another future premier, was secretary. As the fall elections for popular members of the Legislative Council approached, the league presented to a convention held in Yale in September a political program around which to unite those who favoured both confederation and responsible government. In the November votes, pro-confederation candidates were successful on the mainland but not on Vancouver Island. There they were defeated by an alliance of the governmental and HBC élites, who upheld the status quo, with the European-born businessmen who favoured annexation to the United States rather than to Canada. De Cosmos was himself defeated in Victoria City, which returned Helmcken, a former speaker of the Vancouver Island House of Assembly, HBC surgeon, and Douglas’s son-in-law, and Helmcken’s running mate Montague William Tyrwhitt-Drake. The next meeting of the Legislative Council reflected these results. The colonial officials and magistrates who made up the majority joined with Vancouver Island anti-confederates in passing a motion calling confederation “undesirable, even if practicable.” Only the five popular members from the mainland dissented.

This was the last anti-confederate success; by the time the 1870 Legislative Council met, the roadblocks to confederation had been removed. The North-West Territories had been transferred to Canada. Governor Seymour had died and his successor, Anthony Musgrave*, was instructed to work toward British Columbia’s entry into confederation. Finally, the officials on the council were won over by promises of pensions or other colonial appointments. The stage was thus set for a major debate on the terms proposed by the governor for union with Canada. De Cosmos was back on the council, having won decisively in a “by-election” in rural Victoria District fought on the issue of confederation. For him and the other reformers, the key question was responsible government, which was not provided for in the terms. Although differing on tactics, De Cosmos, Robson, and their allies fought to have responsible government included. Balked by the official majority, they turned once more to political agitation outside the legislature. A mass meeting and a delegation calling for responsible government changed Musgrave’s mind, since the governor felt he could not afford to fail in bringing British Columbia into confederation, as he had done in Newfoundland.

Some contemporaries and later commentators have questioned De Cosmos’s enthusiasm for confederation at this time. Musgrave felt that if De Cosmos could have achieved responsible government without confederation he would no longer have been interested in the larger union. The point seems to be, however, that for De Cosmos, as for his great opponent Dr Helmcken, union was a matter of terms. The most important of these for all British Columbians, and the one that smoothed colonial acceptance of entry into the Dominion of Canada, was the latter’s promise to commence within two years and complete within ten a transcontinental railway. But while Canada’s failure to fulfil this term would later dominate De Cosmos’s career as an mp, during the confederation period he remained most concerned with achieving a democratically elected assembly. He continued to fight for its immediate introduction through the 1871 session of a revamped Legislative Council now made up of 9 elected and 6 appointed members. In this he was defeated by a majority led by Helmcken and composed of all the non-elected officials, who by their actions delayed the creation of a wholly elected assembly operating under the principle of responsible government until after confederation had been proclaimed. Once British Columbia had formally joined Canada on 22 July 1871 a Legislative Assembly, consisting of 25 elected members, was created. De Cosmos retained his seat for Victoria District and was at the same time elected mp for Victoria in the series of by-elections that added six members to the House of Commons from the new province.

With the defeat of John Foster McCreight*’s transitional administration in British Columbia on 19 Dec. 1872, Lieutenant Governor Joseph William Trutch* called on De Cosmos, whom he had ignored in choosing British Columbia’s first premier, to form a new government. As the Vancouver World would note in 1897, De Cosmos had for many years been “the rallying cry of the predominant political party in British Columbia,” and his political stature in 1872 remained such that his claim to the premiership could no longer be denied. On 23 December he formed the first of a series of governments comprising men, usually born or raised in North America, who had fought for reform and confederation in the 1860s. Although De Cosmos served as premier only until 1874, this group would remain in power almost continuously until early 1883, opposed by members of the province’s British-born élite. Significantly, John Robson, the other major reform figure, was not included in the cabinet and gravitated to the opposition, an alignment that reflected his association in the Colonist with David William Higgins, De Cosmos’s most implacable enemy.

De Cosmos’s short tenure as premier, during which he was mostly absent in Ottawa and London, passed without notable legislative achievement. Emphasizing reform and economic expansion – the twin goals of his entire political career – his government continued the policy begun by McCreight of implementing a system of free, non-sectarian public schooling, reduced the number of public officials, extended the property rights of married women, and adopted the secret ballot. More significant was the introduction of fully responsible government in British Columbia. At the first meeting of his new cabinet, De Cosmos ended the practice followed during the McCreight administration of having the lieutenant governor sit with the Executive Council to advise ministers. One of De Cosmos’s major initiatives as premier brought his ministry into an acrimonious political dispute. To promote economic growth he tried to alter the term of union concerning Ottawa’s responsibility to guarantee the interest on a sum not exceeding £100,000 for a dry dock at Esquimalt for ten years from the date of the dock’s completion. De Cosmos needed development capital to start the project and went as special agent of the province to Ottawa and London to secure funds. He succeeded in obtaining a commitment from the Macdonald government (renewed by Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie at the end of 1873) for a federal grant of £50,000 in lieu of the interest guarantee, as well as a loan to the province of $1,000,000 at five per cent for other public works. The imperial government conceded a loan of £30,000. Yet when De Cosmos returned to Victoria at the end of January 1874 with what was good news about a major project, his political opponents succeeded in stirring up a storm of criticism.

At the time the British Columbia campaign for the 1874 dominion elections was in full swing, election day in that province having been delayed to 20 February. De Cosmos’s opponents, grouped around Colonist proprietor Higgins and including Helmcken, with Robson as their spokesman in the provincial legislature, were sponsoring two candidates in Victoria in the expectation that De Cosmos, elected in 1871 and 1872, would stand for re-election. Playing on the fear that the railway terminus, given to Victoria in 1873 by Macdonald, would be lost to the mainland, they charged that opening the term of union on the dry dock would also permit alteration of the railway clauses to Victoria’s detriment. The group organized a large public meeting on the evening of 7 Feb. 1874 and led a mob that invaded the legislature, forcing it to adjourn in confusion. Two days later both De Cosmos and Arthur Bunster, his fellow representative in the provincial riding of Victoria District, resigned to contest the federal election. (According to an act passed in 1873 under the De Cosmos administration, dual representation was to be abolished upon election of a new House of Commons.) De Cosmos’s opponents pursued him with a petition presented in the assembly on 9 February and, after his resignation, with charges made by Robson that he had “extorted” $150,000 from Macdonald and that he had misused his office for personal financial advantage in helping to promote an iron mine on Texada Island. The extortion charge was eventually dropped. De Cosmos won the election by four votes over Francis James Roscoe, the candidate backed by the Colonist. A provincial royal commission that met in the late summer and early fall absolved De Cosmos of any wrongdoing in the Texada Island promotion, but the accusations had succeeded in creating an odour of corruption.

The charge that protesters hurled at De Cosmos, of being a “traitor” to local interests, was ironic given his history in public life and false given that the agreement he had made (approved by the legislature once the misunderstanding was cleared up) concerned the dry dock and the debt, not the railway. Yet the accusation undoubtedly steeled his resolve to fight even harder to have the Canadian Pacific Railway built soon, and as far as Vancouver Island. The issue was not new to De Cosmos. Failure of the terms of union to guarantee Victoria’s place as terminus for the projected transcontinental line had become an obsession for him, starting with a series of articles in the Daily Standard in 1873. By 1874 his long-term commitment to advance Victoria’s interests and the immediate circumstance of federal railway policy had forced him into the corner of narrow localism, blurring his dedication, from the 1860s, to “nationalism.”

In the House of Commons, De Cosmos defended the terms proposed in 1874 by the colonial secretary, Lord Carnarvon, especially a clause stipulating that the Esquimalt–Nanaimo portion of the national line be started immediately [see Andrew Charles Elliott*]. He opposed any suggestion that the Island railway be merely a local one, or that compensation be made for limiting the trunk line to the mainland. He spoke about the feasibility of a route by way of Bute Inlet to Esquimalt, declaring that the town’s harbour was unmatched by that of rival Burrard Inlet. His tactics included a motion in early 1879 to provide for the peaceful separation of British Columbia from Canada. Though it failed for want of a seconder, the secession motion reflected the frustration of Vancouver Islanders after the Mackenzie government had finally chosen the Fraser River route in 1878. In 1880 the provincial government appointed De Cosmos special agent to Ottawa, charged with persuading the dominion government to build an Island section of the CPR. When this attempt failed, De Cosmos proceeded to London to petition the queen regarding the dominion’s railway obligations to Vancouver Island. He returned to Canada empty-handed in November 1881 and was relieved of his special duties the following year. Agreement to build an Island line would finally come with the concurrent settlement acts passed by the province in December 1883 and the dominion in April 1884 [see William Smithe*].

The issue of race also demanded increased attention from De Cosmos in the final years of his public career. His views on native Indians and Chinese immigrants always reflected settlers’ values and stereotypes. In the 1880s he spoke of both Indians and Chinese as “inferior” peoples; it had been particularly in the early years of the gold-rush, when Indians roamed the streets of Victoria, that he thought them so. He portrayed Indians as “irrational” yet generally susceptible of “improvement” and “redemption” if removed from the worst influences of whites and trained in “civilized” occupations, especially agriculture. Chinese immigrants, while less degraded, represented a more fundamental threat because they “did not assimilate.” At the same time, De Cosmos’s desire to promote economic growth and his recognition that minority groups could provide much-needed labour softened these negative stereotypes. Thus he praised the Indians’ contribution to the market economy through fishing and agriculture. The Chinese too, he noted on several occasions in the 1860s, would prove immensely helpful in unlocking the region’s vast storehouse of wealth. But racial animus in British Columbia intensified as the province’s settler population grew, and the ambiguity that had earlier marked De Cosmos’s opinions on minority questions lessened. He informed the House of Commons in 1877 and again in 1880 that British Columbia whites were becoming increasing frustrated with the federal government’s Indian land policy. Concessions of land to Indians were over-generous, De Cosmos argued, blocking legitimate white settlement. In addition, he now opposed recognition of Indian title to land, which he had previously supported, and urged that Indians no longer be treated as “a privileged class.” The Indian should be taught “to earn his living the same as a white man.” Anti-Chinese feeling increased most noticeably among Victoria’s growing white working class, who felt that Chinese labourers competed unfairly with white workers. Although De Cosmos tried to keep pace with this mounting racial hostility, it was Noah Shakespeare* and his supporters in the Workingman’s Protective Association who led the anti-Chinese movement. The 1,500-name petition that De Cosmos introduced in parliament in 1879 had been drawn up by Shakespeare. Significantly, in the 1882 federal election it was Shakespeare, running on a stridently racist platform, who defeated De Cosmos, thus ending his career as mp for Victoria.

It is generally conceded that De Cosmos’s tenure as a member of the dominion parliament was undistinguished. Circumstance betrayed him, and the belief of citizens of Victoria that future prosperity depended on the termination of the CPR at Esquimalt forced him into a one-dimensional role as critic of the terms of union. He found himself increasingly isolated as the railway issue alienated him even from other British Columbia mps.

But De Cosmos’s unusual personality also contributed to his ineffectiveness outside the smaller, more intimate surroundings of Victoria. His personal style was regarded as “very eccentric,” from his adopted name to his apparel, typically “a frock coat, top hat, and big-handled stick hung on the forearm, and not used for locomotion.” He was, by all accounts, “a most egotistical man” who “had a habit of talking to you in a very lofty or superior manner.” Well read and able to cite Adam Smith or John Stuart Mill in his writings or debates, he left at his death one of the finest libraries in British Columbia. He was a “free thinker” in religious matters and opposed the introduction of prayers into the House of Commons in 1877. He was also strongly opinionated, given to outbursts of temper and prone to take political issues personally, using caustic language and invective against his opponents. A bachelor, he had many political friends but little private life. His frequently intemperate behaviour in public – for example, his breaking into tears while speaking or his fighting with fists and walking stick on Victoria streets – suggests perhaps a tendency to emotional imbalance. He was not, in the words of G. M. Sproat, a “patient partyman,” and lacked the “diplomatic quality” of a statesman. While in London in the mid 1870s, De Cosmos “caused much amusement generally by his language and demeanor,” and the colonial secretary, Lord Kimberley, in 1881 found him “a fearfully tedious man.” Interestingly, his eccentricities had proved less of a liability on Vancouver Island than on the national and international stages. His success in getting elected regularly in Victoria to local and national legislatures testifies to “legislative abilities of no mean order” and recognition as a “friend of the people.”

After his defeat in the 1882 election De Cosmos remained in Victoria, wandering along city streets in his familiar garb, occasionally brawling with old opponents, sometimes incoherent in his public utterances. His decline was gradual, and he was still held in high enough regard in 1889 that a group of citizens joined him to promote a railway/ferry system between Victoria and the mainland. But the process went on until, in late 1895, at the age of 70, he was declared “of unsound mind.” He died in this state on 4 July 1897.

The two Victoria newspapers founded by Amor De Cosmos were examined systematically for the period during which he was their editor: the British Colonist (1858–60, continued as the Daily British Colonist, 1860–63) and the Victoria Daily Standard (1870–73).

PABC, Add. mss 14; Add. mss 470; GR 1304, file 1897/2139; GR 1372, F447, 1891. B.C., Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1872–74; 1875, “Sessional papers,” 181–274; Legislative Council, “Debate on the subject of confederation with Canada,” Government Gazette Extraordinary (Victoria), March–May 1870; repr. as Debate . . . (Victoria, 1870; repr. 1912), and also in Journals of the colonial legislatures (see below), 5: 444–575; Statutes, 1872–74. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1875–82. Journals of the colonial legislatures of the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, 1851–1871, ed. J. E. Hendrickson (5v., Victoria, 1980). Acadian Recorder, 6 July 1897. British Columbian, 12 Aug. 1882. Daily British Colonist, 1864–82. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 6 July 1897. Monetary Times, 9 July 1897. Vancouver Daily World, 6 July 1897. Victoria Daily Times, 5 July 1897. H. R. Kendrick, “Amor De Cosmos and confederation,” British Columbia & confederation, ed. W. G. Shelton (Victoria, 1967), 67–96. Ormsby, British Columbia. Margaret Ross, “Amor De Cosmos, a British Columbia reformer” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., Vancouver, 1931). Roland Wild, Amor De Cosmos (Toronto, [1958]). George Woodcock, Amor De Cosmos, journalist and reformer (Toronto, 1975). Beaumont Boggs, “What I remember of Hon. Amor DeCosmos,” British Columbia Hist. Assoc., Report and Proc. (Victoria), 4 (1925–29): 54–58. Daily Colonist, 14 March 1943, 12 March 1967, 12 Dec. 1972 (magazine). A. G. Harvey, “How William Alexander Smith became Amor de Cosmos,” Wash. Hist. Quarterly (Seattle), 26 (1935): 274–79. Pacific Tribune (Vancouver), 27 June, 11 July 1952. Margaret Ross, “Amor DeCosmos, a British Columbia reformer,” Wash. Hist. Quarterly, 23 (1932): 110–30. W. N. Sage, “Amor De Cosmos, journalist and politician,” BCHQ, 8 (1944): 189–212. Vancouver Sun, 24 June 1958. Victoria Daily Times, 19 Jan. 1906, 28 Dec. 1929.

Cite This Article

Robert A. J. McDonald and H. Keith Ralston, “DE COSMOS, AMOR (William Alexander Smith),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/de_cosmos_amor_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/de_cosmos_amor_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert A. J. McDonald and H. Keith Ralston |

| Title of Article: | DE COSMOS, AMOR (William Alexander Smith) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |