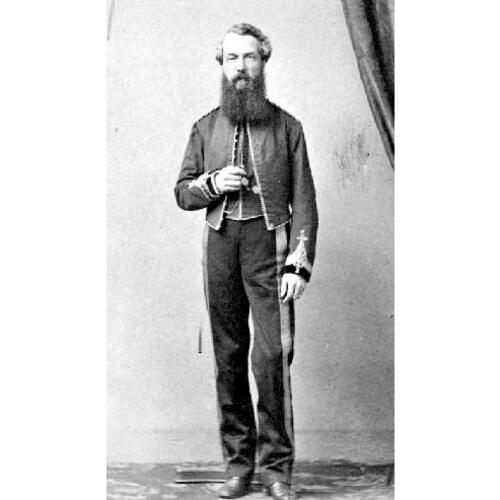

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MOODY, RICHARD CLEMENT, soldier, colonial administrator, and public servant; b. 13 Feb. 1813 at St Ann’s Garrison, Barbados, West Indies, second son of Thomas Moody, re; m. in 1852 at Newcastle upon Tyne, England, Mary Susannah, daughter of Joseph Hawks, justice of the peace and banker, and they had 11 children; d. 31 March 1887 at Bournemouth, England.

Richard Clement Moody’s father, who had been private secretary to several important officials in the West Indies, was seconded to the Colonial Office in 1824 because of his knowledge of the islands. Richard was educated in England by a tutor and at private schools. At the age of 14 he entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich (now part of London), leaving in December 1829 to obtain instruction in the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain. Gazetted 2nd lieutenant in the Corps of Royal Engineers on 5 Nov. 1830, he was posted to the Ordnance Survey of Ireland in 1832. The following year, he was posted to St Vincent, West Indies, and from July 1838 to October 1841 he was professor of fortifications at Woolwich. Between these postings he suffered two of the serious illnesses which were to mark his army life. On 23 Jan. 1835 he was promoted 1st lieutenant.

In 1841 Moody was named lieutenant governor of the Falkland Islands, a region considered of some importance because of the interest in Antarctica. His report on the natural features of the islands won him commendation, and in 1843 he was appointed the first governor and commander-in-chief of the islands and their dependencies. The British government being unwilling to spend funds, Moody employed the small garrison force to erect buildings. He governed with the aid of an Executive and a Legislative Council. The colonists, though they liked him, did not credit him with doing much for development: no survey was made and no system of land tenure devised.

On his return to England, Moody was promoted 1st captain in August 1849. He served briefly on special duty at the Colonial Office, and then rejoined the Royal Engineers in November. After being given command of Newcastle upon Tyne, he served in Malta, where he was promoted lieutenant-colonel in January 1855. He commanded the Royal Engineers at Edinburgh with some distinction and his ability as a draughtsman, evident in a plan for the restoration of Edinburgh Castle, attracted the attention of the secretary of war. On 28 April 1858 he was promoted brevet colonel.

A few months later, on 23 August, Colonel Moody accepted at a salary of £1,200 the appointment of chief commissioner of lands and works and lieutenant governor of British Columbia. The War Office also made him commander of the British Columbia Detachment, Royal Engineers, a corps to be sent to the new colony created by act of parliament on 2 August.

Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, secretary of state for the colonies, had selected the Corps of Royal Engineers because of its “superior discipline and intelligence.” Alarmed by the threat of American control of the Fraser River gold-fields, and knowing the only protection on the coast was a small force of Royal Engineers surveying the land boundary line and of marines from hms Plumper and hms Satellite surveying the water boundary, Bulwer-Lytton anticipated the request for aid sent by Governor James Douglas* of Vancouver Island. The Colonial Office asked the War Office to recommend a field officer for a corps of 150 (later increased to 172) sappers and miners: “a man of good judgment possessing a knowledge of mankind.” The War Office chose Moody; in his favour for a position that would combine military and civil duties were his good military record, his experience as colonial governor, and his father’s reputation. Moody’s appointment was for one year from his arrival in the colony, with an extension possible if he notified the British government it was necessary. Both Moody and Douglas, sworn in as governor of British Columbia in November 1858, were informed that the imperial government would pay only the governor’s salary, that the colony was to be self-supporting, and that the cost of the Royal Engineers was to be defrayed from land sales.

The force Moody commanded included three captains (Robert Mann Parsons, John Marshall Grant, and Henry Reynolds Luard), two subalterns, and a surgeon. For a commissary officer Moody made use of Captain William Driscoll Gosset, a retired Royal Engineer, who had been given a civil appointment as treasurer. Gosset proved as incapable as Moody of keeping account of expenditures and created enormous difficulties for Douglas by his mismanagement of the Assay Office. The men in the British Columbia Detachment received colonial pay varying from one to five shillings a day, an amount higher than the three shillings paid to the Royal Marines who were to supplement Moody’s labour force in 1859. The sappers and miners were also promised a grant of 30 acres of land after six years of continuous service. By 1862 the annual cost of maintaining the Royal Engineers in British Columbia had risen to £22,325.

So little was known in London about the distant colony that the duties assigned the force were legion. Moody, keeping military considerations in mind, was to select, with the governor’s approval, a site for a capital city and a maritime town where customs duties could be collected. He was to choose town sites which had a military advantage. The Royal Engineers were to build public works – they were sent, Bulwer-Lytton said, for scientific and practical purposes, “not solely for military objects.” They were to survey town sites and country lands, plan and engineer roads, and examine harbours. Moody was to report on the mineral wealth, the fisheries, and other resources. The principal obligation excluded from duty was police work – a matter in which Colonel Moody immediately involved himself.

At the Colonial Office there was some suspicion that Moody might not show proper respect for Douglas, the able governor of Vancouver Island, who had spent his life in the fur trade. Bulwer-Lytton met with Moody several times to emphasize Douglas’ authority, and gave him detailed written instructions. Officials at the Colonial Office later admitted Moody’s position had not been well defined. From his subsequent actions it is also evident that Moody read too much into a letter by Herman Merivale, undersecretary of state for the colonies, which referred to his position as “special” and promised that his duties would be free from interference “except under circumstances of the gravest necessity.” Years later, Moody blamed his difficulties on the fact that he was put “in a false position, not of my own seeking, but at the earnest solicitation of the Secy of State.”

Two groups of the Royal Engineers reached Victoria in October and November 1858. The main party reached the colony on 12 April 1859, two months after 139 Royal Marines had arrived from the China Station. Moody, his wife, and four children had departed from Liverpool on 30 Oct. 1858 to travel by the Panama route, and reached Victoria on 25 December. En route they met young men of their own class seeking employment or adventure in the gold-fields. They thus arrived with a circle of friends whose social ties set them apart from Douglas. Two days after his arrival Moody sent the first of his many private letters to the Colonial Office. He had entirely disarmed Douglas “of all jealousy,” he reported. “I have assured him I understand my instructions to be that I am entirely under his orders and that he will find me support him loyally. . . .” Moody’s penchant for writing private letters was criticized as “an objectionable and unfair practice” by officers of the Colonial Office who felt they “ought to take care that no man finds that he has gained an advantage over the Governor of a Colony.”

On 4 Jan. 1859 Moody was sworn in at Victoria as chief commissioner of lands and works and lieutenant governor of British Columbia. Douglas intended to appoint him to the Executive Council which he planned for the colony, but in April he learned that Moody’s commission as lieutenant governor was dormant, operative only “in the event of the death or absence of the Governor.” Since his own commission gave him wide powers, Douglas decided to postpone setting up a council and to govern by proclamation. Moody resented his exclusion from the law-making process since he had the power to govern during the governor’s frequent absences from the gold colony, but he deferred to him and abstained from assuming office on these occasions.

Before leaving England, Moody had decided from maps that the high north bank of the Fraser River had strategic importance and that military reserves should be established near the river’s entrance. Douglas had told him of a site above Annacis Island that would probably be suitable for the seaport. As Moody journeyed up the Fraser early in January 1859, his attention was arrested by a location in this vicinity which seemed ideal for the site of the capital city. But on reaching Fort Langley on 6 January he learned that trouble had broken out among the miners at Hills Bar. With what Douglas called “admirable promptitude,” Moody left at once for Yale, accompanied by Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie*, a lieutenant of the Plumper, and the 22 engineers of his advance party, already at Langley. At Yale, Moody went unarmed to the miners’ camp and was saluted by them. Aware of Moody’s military support, the notorious California outlaw Ned McGowan surrendered, to be tried by Judge Begbie and fined. Order was restored. “The glory being won – the bills now have to be paid, to the tune of 10,000 dollars,” declared Amor De Cosmos* in the British Colonist. “British Columbia must feel pleased with her first war, – so cheap – all for nothing.” The cost had been increased by Moody’s ordering up from Langley to Hope 30 Royal Marines from the Plumper and two field pieces.

hms Plumper, sent to Langley to provide aid, conveyed Moody on his further examination of the river sites. Douglas had had Joseph Despard Pemberton, the colonial surveyor of Vancouver Island, lay out a town site of 900 acres, called Derby, adjoining the Hudson’s Bay Company’s reserve at Langley, on the south bank of the Fraser. Lots had been sold at an auction in Victoria on 25 Nov. 1858, bringing in a revenue of £13,000. It was generally assumed that this site would be the capital of the colony. Moody saw at a glance that Derby was too close to the American border. Descending the river he decided the location he had noticed earlier on the north bank was a site “in which a Military Man wd delight” and suited to serve the double function of capital city and seaport. On 28 January, “in a spirit of entire deference to my chief,” he recommended it to Douglas.

On 1 February the governor ordered immediate surveys; on 4 February he forwarded Moody’s report to the Colonial Office, indicating his approval; the following day he requested Queen Victoria to choose a name for the site the Royal Engineers called Queenborough. On 14 February Douglas issued a proclamation stating that this was to be the site of the capital city, and notifying purchasers of Langley lots that these could be surrendered and the money used to pay for lots in the proposed city. On 17 February he approved the construction of a residence for the lieutenant governor, barracks, a small church, offices, and a customs house. In retrospect, he acted with dispatch, but the Moodys considered him a “dillydallier” for not issuing his proclamation earlier. In London, Merivale received with relief the news about the agreement over the location of the capital but from this time on relations between Douglas and Moody were seldom harmonious.

Moody’s site was on a steep hillside, thickly covered with cedar, fir, spruce, and hemlock. The undergrowth was impenetrable. Pemberton thought the location too heavily timbered, too elevated, and too expensive to grade; its impregnability might be unquestionable, but “if . . . this quality renders it inaccessible to the merchantmen of the Pacific, and to the trade of the Puget Sound, what object could an enemy have in attacking it?” It was three months before the Royal Engineers, with assistance from Royal Marines and civilians, felled the trees and the hillside was turned into “the imperial stumpfield.” The streets were not properly laid out when town lots to the value of £89,170 were sold. One mile distant, however, the Royal Engineers’ camp at “Sapperton” was taking shape, with a barracks, a guardroom and cells, storehouses, and a powder magazine.

Moody had been instructed in England not to employ civilian surveyors, but did so until the governor, annoyed at the cost and the methods used, dismissed them on 27 June. In August, when Moody’s requisitions rose to £25,000, the marines were withdrawn. “He has no power to employ anyone,” Mrs Moody wrote her mother. “Indeed now he has no civilians under him & it only requires him to speak well of anyone to the Govr for him to determine not to do so for them!”

On 22 July 1859 Douglas proclaimed New Westminster, the choice of the queen, as the name of the city. He made it a port of entry and established customs duties. Merchants, who had already arrived, were as distressed as he about the slow progress with public works. “Hurried designs in so grave a matter as the grades for a Capital of a country, cannot be too strongly deprecated,” Moody told the governor in December. “I would suggest to you that the Colony itself must first become great and flourishing before we can undertake works on a scale of magnificence,” Douglas replied, “and that a Town just laid out and not yet disassociated from the primeval forest cannot be dealt with as a great City that has existed for Centuries.”

During Moody’s first year in the colony little advance was made on Douglas’ priorities of road-building and the survey of country lands. Miners were flocking to the interior, and improved communication was imperative. In May and June 1859 the Royal Engineers had surveyed and improved the 123-mile Harrison-Lillooet trail which Douglas had opened with volunteer labour in the winter of 1858–59. But men had been diverted from converting the trail into a wagon road to resurvey Port Douglas (Douglas), Yale, and Hope. A six-mile trail, costing from £60 to £70 a mile, had been built for military purposes to connect New Westminster with Burrard Inlet (the North Road), and a route from Hope to Lytton had been explored. The London Times on 30 Jan. 1860 reported: “Soldiers cannot be expected to do this sort of work. The impedimenta they carry with them, the costliness of their provisions and of their transport, the loss of time in drilling and squaring and scrubbing and cleaning them, make them the most expensive of labourers.” New Westminster’s merchants found the lack of roads handicapped their opportunity to provision the mines. They demanded that public works proceed at a faster pace and that they be given a voice in government. On 16 July 1860 Douglas yielded partly by permitting local self-government through incorporation of the city, thereby shifting the cost of local improvements to the citizens. The higher level of taxation led to complaints that Douglas was shackling the development of the city as a commercial centre.

In the spring of 1861 a memorial was prepared by the residents of New Westminster for the Duke of Newcastle, now colonial secretary, complaining about money “most injudiciously squandered,” contracts for roads awarded without public advertisement, faulty administration of public lands, and government reserves set aside for the benefit of government officers. Angered by these charges, Douglas demanded that Moody, the chief commissioner of lands and works, inform him about any government officer who had acquired land from the government except at a public auction or who had registered a pre-emption. The records did show purchases by Moody and his associates. The newspapers provided more information. The British Colonist had reported on 4 Oct. 1860 that Moody had stuck a paper on a tree at Red Earth Fork (Princeton) to pre-empt 200 acres, and in February 1861 the New Westminster British Columbian published a letter from “a farmer” alleging Moody was guilty of land-grabbing. Finally on 29 Aug. 1861 Moody announced his intention to sell his rural land to actual settlers, although he retained a large suburban lot near New Westminster bought with Douglas’ permission in 1859 and then developed into his model farm, Mayfield. As late as 1873 he held 3,049 acres of land. In a June 1861 letter to Douglas he had tried to shift blame for any wrongful disposal of crown lands to the district magistrates, who were responsible for “all matters relating to un-surveyed Lands, viz – those open to preemption.” To the charge that the Royal Engineers’ surveys had been “desultory” he replied that this was the result of too frequent requests having been made for them to supply other services.

The governor believed that British Columbia could never become great or prosperous without a highway system, and that it was imperative the miners be supplied with food at less than famine prices. At his urging, the officers did concentrate most of their attention on the road system. Captain Grant completed the Douglas–Lillooet road in 1860, and the next year he built 25 miles of the wagon road from Hope to the gold mines on the Similkameen and at Rock Creek. The Yale to Lytton road following the Fraser River was surveyed in 1861, and in 1862 Douglas ordered construction to begin on his project, the 400-mile wagon road from Yale to the Cariboo. The “Great North Road” was Douglas’ conception. Moody had been asked in October 1861 to produce a plan, but had declined because he was unfamiliar with the country. Douglas sent a stinging rebuke for failure to learn about the interior. In March 1862 Moody produced a plan for two roads in addition to the Fraser River highway, but the governor had “no desire to foster these undertakings” and, on his orders, Captain Grant commenced work on the Great North Road in May 1862 with 53 sappers. They built the first six miles north from Yale through the solid rock face. An equally difficult stretch of nine miles from Spence’s Bridge along the Thompson River was also built. The greater part of the remainder of the road was let out on contract to civilians who received cash or bonds or the right to collect tolls. Three officers, captains Grant and Luard and Lieutenant Henry Spencer Palmer, gave invaluable service either in building a part of the road or in supervising the contractors. In October 1863 at Yale the Royal Engineers conducted the opening ceremony of the highway.

Moody’s heart was in military projects, not roads. When the crisis over San Juan Island culminated in 1859 in joint British and American military occupation of the island, the defence of New Westminster, which had “great facilities for communication by water, as well as by future great trunk railways into the interior,” was uppermost in his mind. The imperial government would not agree to a military frontier settlement on the south bank of the Fraser River across from New Westminster, but it did agree to the setting aside of naval reserves on Burrard Inlet. Moody had New Westminster connected by a road to Port Moody and to the Burrard Inlet, future site of Vancouver.

Under his direction, the Royal Engineers established at New Westminster the first observatory in the colony, printed both the Government Gazette for the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia and maps based on reconnaissances and surveys, built the first churches, and designed the colony’s first postage stamp and its coat of arms. Moody was civic-minded: he helped to found the hospital and the industrial exhibition at New Westminster, and his library became the foundation of the city’s public library. Though he was not robust, and overwork caused him to look “so old & grey,” the citizens of New Westminster knew him as a friendly, even jolly man – “cheerie like,” his wife said. John Robson*, the fiery editor of the British Columbian, was under his spell and wanted him to be governor of British Columbia.

As early as January 1860 the Colonial Office felt that it had been a mistake to give Moody a civil appointment, and also to send the Royal Engineers: “The labor of the Engineers as surveyors is neither economical nor adapted to a country were rapidity of work is the chief requirement.” The San Juan dispute saved them from withdrawal, and Newcastle postponed a decision until his return from accompanying the Prince of Wales to Canada. Evidence of Moody’s unsuitability accumulated: his “imperfect method in conveying public lands,” his penchant for writing letters, and his extravagance. In accord with his usual practice, Douglas minimized his difficulties. He informed the Colonial Office that he and Moody were “uniformly cordial, confidential and friendly,” and he praised Moody for his “mild, conciliatory and gentlemanly bearing.” By 1862, however, he realized that Moody was doing his own reputation harm, and his patience became exhausted. It had become necessary for him, he told Newcastle, to issue the most precise instructions in matters of finance and administration. When the imperial authorities demanded that the colony pay half of all the costs of the Royal Engineers, Douglas told the Colonial Office that they were “a costly ornament,” who were to British Columbia what “the old man of the sea was to Sinbad.”

In April 1863 Newcastle, realizing that Moody had not sought permission for a longer term, and that the colony could not afford the Royal Engineers, decided to withdraw the corps. With the Cariboo mining population swollen to 4,000 persons, it was a bad time to remove the chief commissioner of lands and works, but to leave Moody in British Columbia “with nothing but a subordinate Civil office” was not possible. Douglas hoped to retain Captain Luard’s services, but Moody informed the Colonial Office that Luard was unfit to succeed him as commissioner. Chartres Brew* was given the appointment.

On 6 November the people of New Westminster gathered at a farewell dinner for Colonel Moody and his officers. The Moodys departed with their seven children, 22 officers and men, eight wives and 17 children, leaving behind 130 sappers and miners who had elected to remain.

Moody became a regimental colonel on 8 December and in March 1864 he was given command of the Royal Engineers in the Chatham District in England. On 25 Jan. 1866 he was promoted major-general and retired from the service on full pay. He lived quietly at Lyme Regis in Dorset, hoping always to return to British Columbia, until his death from apoplexy while he was on a visit to Bournemouth.

There was some truth in the Daily British Colonist’s statement of March 1863 that the Royal Engineers had been a clog on the executive. Had Moody been more willing to recognize Douglas’ talents, experience, and knowledge of the country, the governor would have consulted him more frequently and acted less arbitrarily. Moody took an unfair advantage of Douglas in trading on his father’s reputation at the Colonial Office, and in the end his constant complaints wore down Newcastle, who decided not only to disband the British Columbia Detachment but also to retire Douglas early from the governorship.

Richard Clement Moody’s “First impressions: letter . . . to Arthur Blackwood, February 1, 1858,” ed. W. E. Ireland, was published in BCHQ, 15 (1951): 85–107.

PABC, Add. mss 60; B.C., Colonial secretary, Corr. outward, January 1859–September 1863 (letterbook); B.C., Dept. of Lands and Works, Corr., 1859–63; B.C., Royal Engineers, Corr. outward, 1859–63; Colonial corr., R. C. Moody corr.; Crease coll., Moody corr. PRO, CO 60/3–17. G.B., Parl., Command paper, 1859 (1st session), XVII, [2476], pp.15–108, British Columbia: papers relative to the affairs of British Columbia, part i; 1859 (2nd session), XXII, [2578], pp.297–408, British Columbia: papers relative to the affairs of British Columbia, part ii. [M. S. Moody], “Mrs. Moody’s first impressions of British Columbia,” ed. Jacqueline Gresko, British Columbia Hist. News (Victoria), 11 (1977–78), nos.3–4: 6–9. British Columbian, 1861–63. Daily British Colonist (Victoria), 1858–63. Times (London), 6 April 1887. Victoria Gazette, 1859–60. DNB. M. C. L. Cope, “Colonel Moody and the Royal Engineers in British Columbia” (ma thesis, Univ. of British Columbia, Vancouver, 1940). F. W. Howay, The work of the Royal Engineers in British Columbia, 1858 to 1863 . . . (Victoria, 1910). Dorothy Blakey Smith, “The first capital of British Columbia: Langley or New Westminster?” BCHQ, 21 (1957–58): 15–50. K. S. Weeks, “The Royal Engineers, Columbia detachment – their work in helping to establish British Columbia,” Canadian Geographical Journal (Montreal), 27 (July–December 1943): 30–45. Madge Wolfenden, “Pathfinders and road-builders: Richard Clement Moody, R.E.,” British Columbia Public Works: Journal of the Department of Public Works (Victoria), April 1938: 3–4. F. M. Woodward, “The influence of the Royal Engineers on the development of British Columbia,” BC Studies, 24 (winter 1974–75): 3–51; “‘Very dear soldiers’ or ‘very dear laborers’: the Royal Engineers in British Columbia, April 1860,” British Columbia Hist. News, 12 (1978–79), no.1: 8–15.

Cite This Article

Margaret A. Ormsby, “MOODY, RICHARD CLEMENT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moody_richard_clement_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moody_richard_clement_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Margaret A. Ormsby |

| Title of Article: | MOODY, RICHARD CLEMENT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 19, 2025 |