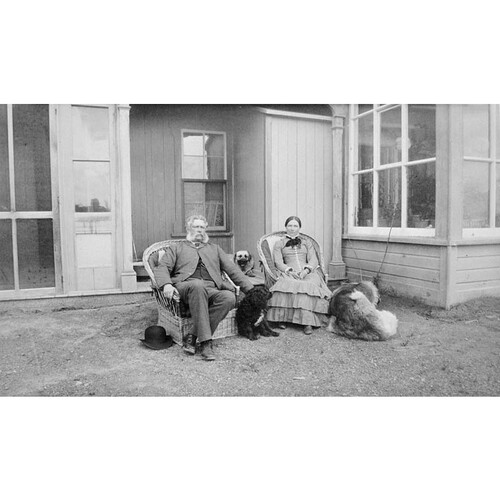

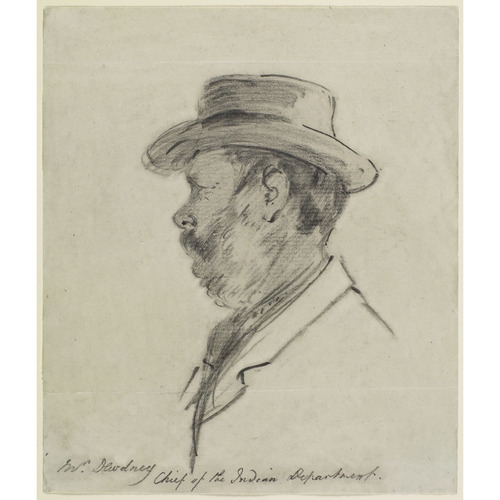

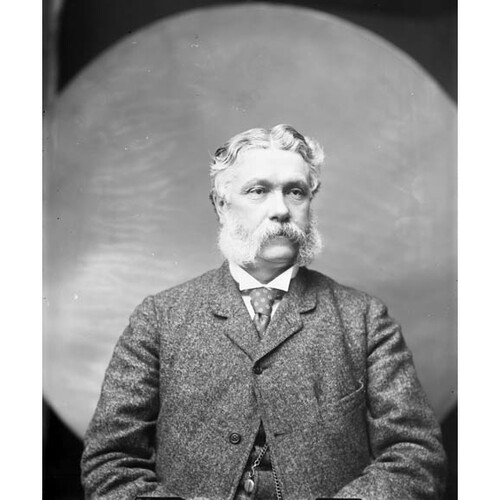

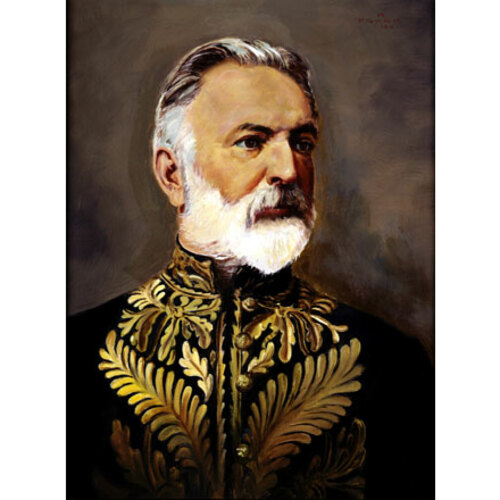

DEWDNEY, EDGAR, civil engineer, contractor, politician, office holder, and lieutenant governor; b. 5 Nov. 1835 in Bideford, England, son of Charles Dewdney and Fanny Hollingshead; m. first 28 March 1864 Jane Shaw Moir in Hope, B.C.; m. secondly September 1909 Blanche Elizabeth Plantagenet Kemeys-Tynte in Somerset, England; no children were born of either marriage; d. 8 Aug. 1916 in Victoria.

Born to a family of means, Edgar Dewdney attended school in Bideford, Tiverton, and Exeter and then went on to Cardiff, Wales, where he trained as a civil engineer. Tall and vigorous, he loved cricket, tennis, shooting, and the outdoors. In 1858 and 1859 British newspapers carried stories of the fortunes being made in the gold-fields of the Fraser valley, in the Pacific northwest, and the young Dewdney decided that this was where he would ply his trade, confident that he would return within ten years a wealthy man. He arrived in Victoria on 13 May 1859. Well connected, he bore a letter of introduction from Colonial Secretary Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton to Governor James Douglas*.

Dewdney immediately found work with Richard Clement Moody* and a contingent of Royal Engineers who were surveying the site of New Westminster, recently chosen to be the capital of the mainland colony of British Columbia. He also assisted in the construction of government buildings and in the sale of town lots. Gold continued to be discovered in various parts of the colony, and to ensure that all the profits were not siphoned off by American traders, the authorities in New Westminster undertook the construction of trails to the gold-fields through British Columbia territory. Dewdney won several of the contracts. In 1860, in partnership with Walter Moberly, he built a pack trail from Hope to the mining camps of the Similkameen valley. Later, in 1865, after gold strikes in the Kootenays, he would extend the trail to Wild Horse Creek (Wild Horse River). Using teams of Chinese labourers, native Indian packers, and discharged men of the Royal Engineers, he completed the extension in a few short months at a cost of $74,000. It became known as the Dewdney Trail and was the principal route to the interior for several years. In 1862 and 1863 he did surveying in the Cariboo country, again associated with gold-mining, and in 1866 he built trails from Lillooet and Cache Creek into nearby gold-mining areas. A year later he settled for a while near Soda Creek and tried his hand at stock raising. Becoming wealthy was still his primary ambition but it continued to elude him.

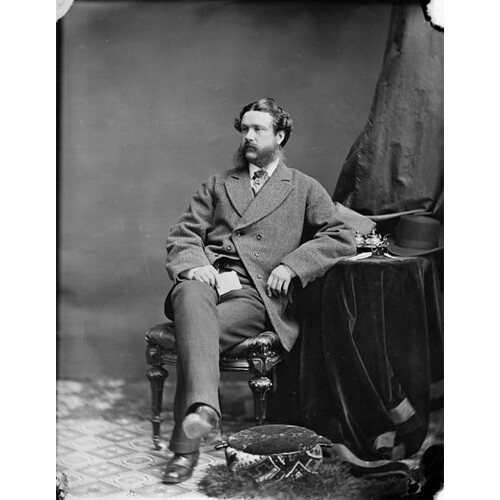

Dewdney’s entry into politics was almost accidental. Without campaigning on his part, he was named in December 1868 to represent Kootenay in the colony’s Legislative Council. During the council debate on union with Canada in the spring of 1870 he supported confederation but opposed responsible government, claiming his constituents did not want it. He resigned shortly afterwards to return to surveying and played no role in the final deliberations that brought British Columbia into Canada in 1871.

By the terms of union Ottawa had promised to build a transcontinental railway, and work began immediately. Dewdney was named a member of Sandford Fleming’s team to survey the route. Politics beckoned once more, however, and he ran successfully for a seat in the House of Commons representing Yale in the general election of 1872. Before leaving for Ottawa he was invited to become surveyor general of British Columbia, but he declined. In parliament Dewdney supported the Conservative government of Sir John A. Macdonald*, which had brought his province into confederation on generous terms. He remained loyal to the Conservative leader after the Liberal victory in 1874 and grew increasingly critical of Alexander Mackenzie*’s government as its commitment to building the transcontinental railway weakened. For Dewdney the line was a matter of first importance. He championed the Fraser valley route with a terminus at Burrard Inlet, which would at once serve the interests of his constituents and his own speculative real estate investments. He was re-elected to parliament by acclamation in 1878. Macdonald was now back in power, and Dewdney was not only a confirmed partisan of the prime minister but a close personal friend.

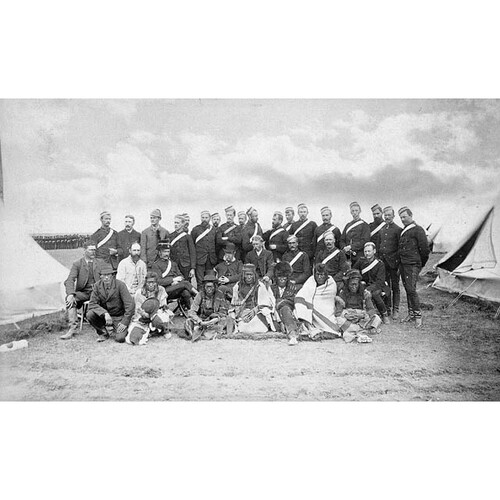

By 1879 the buffalo herds had virtually disappeared from the North-West Territories and the region’s substantial Indian population faced starvation. As their plight became increasingly desperate, they posed a threat to Macdonald’s plan to finish the railway and fill the west with settlers. The prime minister needed a reliable man on the spot to deal with the crisis and he offered Dewdney the newly created post of Indian commissioner of the North-West Territories, at a salary of $3,200 per annum. Dewdney accepted and resigned his seat in parliament. His appointment was effective as of 30 May 1879. He was now the principal officer in the northwest for the Indian affairs branch. His general instructions were to prevent starvation by the distribution of relief, to get those Indians who had not already done so to settle on their reserves and take up agriculture, and to persuade the Sioux refugees led by Sitting Bull [Tatanka I-yotank*] to leave Canada.

Dewdney set out immediately for the west and on 26 June arrived at Fort Walsh (Sask.), the North-West Mounted Police post in the Cypress Hills, where large numbers of starving Cree and Assiniboin had gathered. He spoke with Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa*], distributed rations, and explained that he would help only those who cooperated with government policy. Indians who had signed treaties complained that many of the promises had not been fulfilled and that the cattle and implements they had received were of inferior quality. As he toured other parts of the northwest he heard similar complaints and encountered further scenes of destitution. The Blackfoot in the camp of Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika*] were so desperate that they were eating dogs and gophers. Dewdney concluded that the government would have to feed the Indians for some time. In November he went back to Ottawa to report to the prime minister. While he was there his mandate as Indian commissioner was expanded to include Manitoba and the District of Keewatin. When he returned to the west in the spring of 1880, he established his headquarters in Winnipeg.

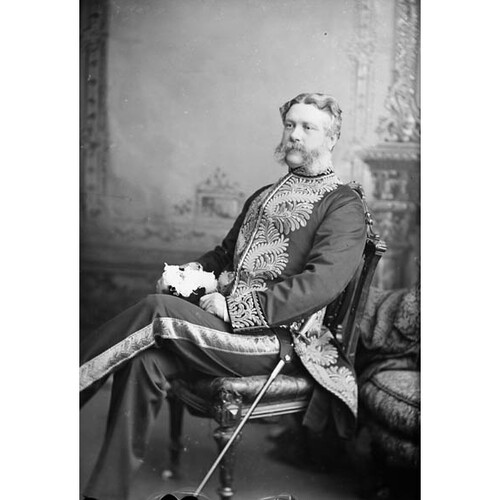

Dewdney found the demands of the job onerous and was hurt by criticism of his appointment in the press. Moreover, his wife, who was the daughter of a tea-planter in Ceylon and had attended boarding school in England, hated the prairies and “Ned’s” long absences from home. In 1881 he asked Macdonald to accept his resignation and give him a seat in the Senate. But the prime minister wanted him to continue and offered to make him lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories as well as Indian commissioner, with an additional stipend of $2,000, upon the expiry of David Laird’s term of office. Dewdney agreed and became lieutenant governor on 3 Dec. 1881. He moved to Battleford (Sask.), the territorial capital; the Indian office remained in Winnipeg under the direction of assistant commissioner Elliott Torrance Galt* and his successor Hayter Reed*, until 14 June 1883, when it was relocated in Regina.

Throughout his years in the North-West Territories, Indian policy remained Dewdney’s principal concern. In May 1880 he had met Sitting Bull and refused the Sioux leader’s demand for a reserve and rations. Starvation ultimately forced the Sioux to return to the United States. For Canadian Indians the government was prepared to provide rations of one pound of meat (bacon or beef) and a half pound of flour per day until they could fend for themselves through agriculture. Seventeen farm instructors, including Samuel Brigham Lucas*, had been sent west to establish “home farms” adjacent to major clusters of reserves. Dewdney’s policy, as directed by Ottawa, was to deny rations to Indians who would not work under the tutelage of these instructors. But while believing in the work-for-rations rule, he was not uncritical of some aspects of the grand scheme. He knew, for instance, that the instructors were patronage appointments, that many of them were incompetent, and that the lavishly supplied government farms were grossly mismanaged. He also knew that many Indians were working as best they could although they were without adequate equipment.

Rations, however, were a weapon that Dewdney did not hesitate to use when faced with resistance to government policy. In 1881 Big Bear was encouraging Indian bands from the Treaty No.4 and No.6 areas to gather in the Cypress Hills. The chief hoped to negotiate better treaty terms and establish contiguous reserves in the area which would have amounted to a semi-autonomous Indian territory. To counter this strategy Dewdney arranged for Fort Walsh to be closed and demanded that the Indians take their reserves in the Fort Qu’Appelle, Battleford, and Fort Pitt areas or have assistance cut off. Faced with starvation, the Indians submitted. Big Bear, although he signed Treaty No.6 in December 1882 and went to his reserve, still hoped to negotiate better terms and his continued agitation remained a cause of concern to Dewdney.

Education was fundamental to Indian department policy on the prairies as it evolved under Dewdney’s guidance. He had great faith in the younger generation of natives, but only if the influence of their parents could be eliminated. Consequently he cooperated closely with the major Christian churches in establishing a network of industrial schools in his domain [see Joseph Hugonard; Albert Lacombe]. The schools were residential, located away from the reserves, and they offered a mixed program of manual and academic subjects. Dewdney saw no reason why this education would not rapidly transform young Indians into paragons of productivity and good citizenship.

During 1883 and 1884 Dewdney promoted a policy of subdividing agencies into more manageable units and placing a growing number of Indian agents and farm instructors on reserves to effect more direct supervision of the agricultural program. In September 1883 deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs Lawrence Vankoughnet toured the northwest and concluded that measures of economy were needed in administering the region. Dewdney protested the subsequent cuts to his budget, explaining to Ottawa that he did not want the Indians to suffer and that he required flexibility in using the work-for-rations policy – but his objections were in vain.

The tough rations policy, the building of the railway, and the steady influx of settlers increased native anxiety in 1884. The Cree were rallying behind Big Bear in pressing their demands for better treatment. And in July Louis Riel* returned from Montana to lead the agitation of the Métis for recognition of their land titles in the District of Saskatchewan. Dewdney sensed a mounting crisis but was receiving mixed messages from his men in the field. Consequently his reports to Ottawa were not as strongly worded as the occasion warranted. By February 1885, however, in the middle of a particularly harsh winter, he was urging that Métis grievances be settled, treaty promises to the Indians fulfilled, and rations increased to avert violence. But he also wanted the authority to arrest Indian chiefs who were provoking unrest.

Before any of these measures could be taken, a clash between the Métis and the police at Duck Lake in March [see Gabriel Dumont*] precipitated the North-West rebellion. Dewdney blamed Riel for the outbreak. During the months of fighting that followed he was primarily concerned with preventing Indians from joining the fray. He made tours of the Treaty No.4 and No.7 reserves, distributing gifts of tobacco and ordering rations to be increased. The strategy paid off, at least in his own estimation, and most Indians remained loyal.

In the aftermath of the rebellion Dewdney favoured strong punishment of the participants. For example he encouraged Macdonald to carry out the death sentence passed on Riel. As for the Indians who had been disloyal, he proposed depriving them of treaty annuities and confiscating their rifles and horses. He also arranged the distribution of rewards to the bands of chiefs such as Crowfoot and Red Crow [Mékaisto*] who had supported the government – extra rations, farm equipment, and money. Indian department administration became increasingly bureaucratic and repressive. Dewdney promoted the further subdivision of agencies, the appointment of additional personnel, such as inspector Alexander McGibbon*, to ensure closer supervision of the Indians, the creation of individual farms on reserves to “strike at the heart of the tribal system,” and the establishment of more industrial schools. Indian agitation for greater autonomy and better treaty terms was finally suppressed [see Payipwat*].

As lieutenant governor Dewdney wielded extraordinary executive power. He was influential in the selection of Regina in 1882 to be the new territorial capital. The site was located on the route across the prairies that had ultimately been chosen by the Canadian Pacific Railway. Having bought land in the vicinity, he profited by its subdivision and sale, an action for which he was widely criticized by Liberal politicians and the Liberal press. He controlled appointments and the spending of federal funds, and his authority was independent of the Council of the North-West Territories, a partly elected, partly appointed body which served as an incipient assembly for the region. As the population of settlers grew, the elected members of the council became increasingly insistent on a larger role in territorial administration. They demanded a responsible executive, representation in parliament for the region, and ultimately provincial status. Dewdney’s policy, in accordance with Macdonald’s wishes, was to keep these demands in check while gradually conceding democratic reforms. In 1886, for example, Ottawa granted four seats in the House of Commons to the northwest and in the following year two Senate seats. And in 1888 the council was transformed into a legislative assembly, but without a responsible executive.

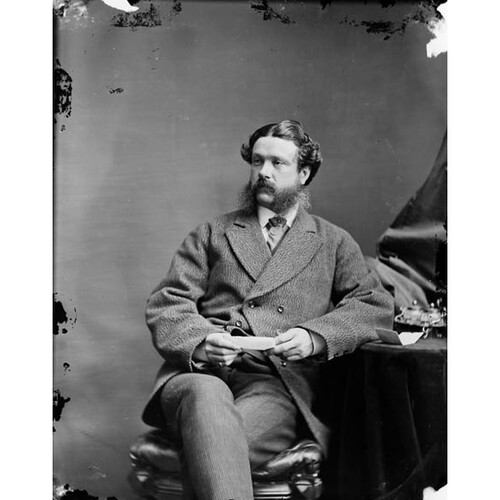

Dewdney had never liked the territories and his wife detested the place. After the rebellion he had asked Macdonald to make him lieutenant governor of British Columbia, but the prime minister had promised the post to someone else. Macdonald trusted Dewdney and appreciated his loyalty (Dewdney would be an executor of his will), and he asked him to stay on in Regina even after his term as lieutenant governor expired in 1886. When Thomas White*, the minister of the interior, died suddenly in the spring of 1888, Macdonald offered his job to Dewdney, who gratefully accepted. He resigned as lieutenant governor and Indian commissioner on 3 July. William Dell Perley, the mp for Assiniboia East, was appointed to the Senate and Dewdney was elected to the House of Commons in a by-election on 12 Sept. 1888.

Dewdney entered the federal cabinet as minister of the interior and superintendent general of Indian affairs, and he was therefore responsible for two departments with whose work he was already familiar. The Department of the Interior took in the dominion lands branch and looked after the Geological Survey of Canada and the administration of the North-West Territories. Thus he found that he still had to deal with the agitation for greater self-government in his former domain. His policy was as before: granting cautious concessions to the territorial assembly while resisting the creation of a responsible executive. In spite of his foot-dragging on the issue, he was again returned to parliament for Assiniboia East in the general election of March 1891.

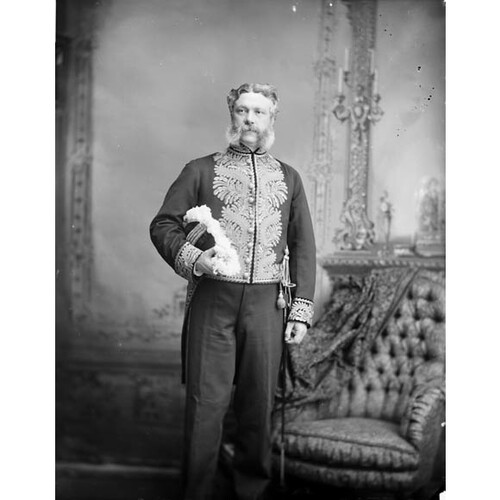

Macdonald died in June, but Dewdney stayed on in the cabinet of John Joseph Caldwell Abbott* until 16 Oct. 1892, when he resigned to take up a long-coveted appointment. On 2 November he became lieutenant governor of British Columbia. Dewdney was a well-known figure by then and his status as a pioneer in the province made him a popular choice as the crown’s representative, although his wife’s snobbery would cause occasional irritation. He managed to stay aloof from the major controversy of his term – Premier Theodore Davie*’s decision to construct elaborate new parliament buildings in Victoria in order to “anchor” the provincial capital there. The lieutenant-governorship involved few responsibilities and numerous social events, and Dewdney enjoyed it immensely. In the autumn of 1894 and the summer of 1895 he hosted Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*] and Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*] on their visits to the west coast. And in June 1897 he presided at the celebrations marking Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee. For a man profoundly attached to the empire and the British monarchical tradition, these were the highlights of his term of office. He retired on 1 Dec. 1897.

Dewdney lived out his retirement in Victoria. Although he had done well in some of his land speculations and had earned good salaries for many years, he had managed money poorly and had no pension. With the Liberals in power in Ottawa there was no hope of a Senate appointment. He therefore went into business, speculating in a number of mining ventures but with mixed results. He tried his hand at politics again, running unsuccessfully as the Conservative candidate for New Westminster in the federal election of 1900. And in 1901 he was practising his surveying profession once more, reporting to the provincial legislature on the feasibility of a railway from Hope to Princeton – the route of the original Dewdney Trail.

At the end of January 1906 Dewdney’s wife died. He lived alone for a while and then in 1909, during an extended visit to England, he married Blanche Elizabeth Plantagenet Kemeys-Tynte, the youngest daughter of a man he had known in his youth. The couple returned to Victoria and she nursed him through his declining years. Money continued to be a source of worry, and after the Conservatives returned to power in Ottawa under Robert Laird Borden* in 1911, he asked for a seat in the Senate or at least a pension in recognition of his years of service. His petitions went unheeded. He died on 8 Aug. 1916 of heart failure and was buried in Ross Bay Cemetery. His widow returned to England where she died in 1936.

Edgar Dewdney was an accomplished engineer, an indifferent businessman, an adequate administrator, and an undistinguished politician. His greatest fault, perhaps, was his partisan loyalty to John A. Macdonald, which clouded his judgement at critical moments. He deserves some of the blame for the North-West rebellion and the repressive policies that followed it. The roads he surveyed in British Columbia were his greatest achievement.

“The starvation year: Edgar Dewdney’s diary for 1879,” ed. H. A. Dempsey, appears in Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 31 (1983), no.1: 1–12 and no.2: 1–15.

The BCARS holds a number of collections directly related to Dewdney and his family, including correspondence of Jane and Edgar Dewdney in the O’Reilly coll., A/E/Or3/D51 and D54; papers concerning his second wife in the same collection, A/E/Or3/D55; various typescript materials in M/D51; and two published addresses by Dewdney, preserved in the Northwest coll.: Speech on the subject of the Canadian Pacific Railway, delivered to his constituents at Cache Creek (New Westminster, B.C., 1875) and Pacific railway route, British Columbia (n.p., [1879?]).

In addition to several photographs of Dewdney, the GA has a major collection of his personal and political papers at M320. Some of this material is also found in the BCARS collections and in the Dewdney papers at NA, MG 27, I, C4.

Because Dewdney spent the main portion of his career in the Department of Indian Affairs, that department’s records contain a vast number of files related to his work. The following is but a small representative sample: NA, RG 10, 3600, file 1752; 3603, file 2043; 3637, file 682; 3646, file 8128: 3664, file 1943; 3671, file 10836; 3708, file 19502; 3709–10, file 19550.

Sue Baptie, “Edgar Dewdney,” Alberta Hist. Rev. (Calgary), 16 (1968), no.4: 1–10. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1880–87, reports of the Indian branch, Dept. of the Interior, 1879, and of the Dept. of Indian Affairs, 1880–86. S. W. Jackman, The men at Cary Castle; a series of portrait sketches of the lieutenant-governors of British Columbia from 1871 to 1971 (Victoria, 1972). Jean Larmour, “Edgar Dewdney: Indian commissioner in the transition period of Indian settlement, 1879–1884,” Sask. Hist., 33 (1980): 13–24.

Cite This Article

E. Brian Titley, “DEWDNEY, EDGAR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dewdney_edgar_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dewdney_edgar_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | E. Brian Titley |

| Title of Article: | DEWDNEY, EDGAR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |