MISTAHIMASKWA (Big Bear, known in French as Gros Ours), Plains Cree chief; b. c. 1825, probably near Fort Carlton (Sask.); d. 17 Jan. 1888 on the Poundmaker Reserve (Sask.). Over the course of his life he had several wives and at least four sons.

Big Bear’s parents are unknown but may have been Saulteaux; he seems to have grown up with the Plains Cree bands that usually wintered along the North Saskatchewan River and hunted south every summer for buffalo. He received his power bundle, song, and probably his name as a result of a vision of the Bear Spirit, the most powerful spirit venerated by the Crees. The power bundle, never opened unless to be worn ritually in war or in dance, contained a skinned-out bear’s paw, complete with claws, sewn on a scarlet flannel. At appropriate times, Big Bear wore the paw around his neck; he believed that when the weight of it rested against his soul, he was in a perfect power position and that nothing then could hurt him.

In November 1862 Big Bear was reported by Charles Alston Messiter to be “the head chief” of a “large camp of Crees” near Fort Carlton. However, Hudson’s Bay Company trader John Sinclair later reported that about 1865 Big Bear “removed from Carlton to Pitt, and became the head man of a small band of his relatives who resided at Pitt, numbering about twelve tents, or perhaps twenty men.” Sinclair knew him there as a “good Indian” but did not acknowledge Big Bear as a chief until much later, which implies less that Big Bear had little authority among his people than that he was too independent to suit either traders or missionaries.

The traditional activities of hunting and warfare occupied Big Bear until the 1870s brought the police, the treaties, and the end of the buffalo. He and his band are known to have taken part in the hostilities between the Plains Cree and the Blackfeet which culminated in the battle at Belly River (near Lethbridge, Alta) in October 1870. Jerry Potts* later reported that between 200 and 300 Crees and 40 Blackfeet were killed; if these estimates are correct, Belly River was the largest Indian battle known to have been fought on the Canadian plains. It was certainly the last.

As the number of whites on the plains increased, so Big Bear was confirmed in his independent spirit. In 1873 he clashed with Gabriel Dumont* when the Métis leader tried to dictate how the buffalo should be run on the summer hunt. In the summer of 1874 HBC trader William McKay was commissioned by the Canadian government to visit the Plains Indians with presents of tea and tobacco and to explain carefully why the North-West Mounted Police were coming. McKay reported that the Plains Cree “all received the presents in a friendly manner,” but that “two families of Big Bear’s band . . . objected to receive any, stating they were given them as a bribe to facilitate a future treaty.” McKay also records that Big Bear’s camp consisted of 65 lodges (about 520 people), while that of Sweet Grass [Wikaskokiseyin*], who as early as 1871 had been named “The Chief of the Country” by the HBC and who had been baptized Abraham by Father Albert Lacombe*, had only 56.

Big Bear proved even more problematic to the Reverend George Millward McDougall*, commissioned in 1875 to “tranquillize” the Plains Indians regarding the treaty Canada planned for them. The Methodist missionary found most of the “principal men . . . moderate in their demands,” but thought Big Bear a mischief-maker because he was “trying to take the lead in their council.” Big Bear had declared: “when we set a fox-trap we scatter pieces of meat all round, but when the fox gets into the trap we knock him on the head; We want no bait; let your chiefs come like men and talk to us.”

Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris came “like a man” in August 1876 to negotiate Treaty no.6, which dealt with the rights to 120,000 square miles of land, and he found Big Bear something more than a mischief-maker. The chief did not come to Fort Carlton, and he only appeared at Fort Pitt on 13 September, the day after all official ceremonies were completed. Sweet Grass and the other Cree and Chipewyan chiefs urged him to sign, as they had, but Big Bear, who said he had been sent to speak for all Crees and Assiniboins still hunting on the plains, replied, “Stop, my friends. . . . I will request [the governor] to save me from what I most dread – hanging; it was not given to us to have the rope about our necks.” Morris concluded that Big Bear was simply a coward; however, since the Crees believed their souls to reside along the nape of their necks, the statement might also be seen as a powerfully prophetic metaphor of what would happen within a decade to all the Plains Indians. In any case, Big Bear did not sign, the first major chief on the Canadian prairies not to do so.

Big Bear refused to take treaty for the next six years, which was as long as the buffalo lasted. His defiance drew more and more independent warriors to his camp. He met the new lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories, David Laird*, at Sounding Lake (Alta) in August 1878, but he would neither sign nor accept presents, and so there could be no question of his designating a reserve. In October the band led by Little Pine [Minahikosis] discovered surveyors near the present site of Medicine Hat (Alta); the chief claimed they had no right to survey and sent for Big Bear who was at the Red Deer Forks (Sask.), while the surveyors sent for the police at Fort Walsh (Sask.). Colonel Acheson Gosford Irvine agreed with Big Bear that the surveyors should stop their work until the matter was settled between Big Bear and the lieutenant governor “when the leaves come out.”

In the winter of 1878–79 Big Bear was at the height of his influence; the buffalo had not come north that winter (they never would again in numbers) and the plains people now understood that their tiny reserves and $5 annual payments would mean nothing if the hunting, which Morris had assured them would continue as before, were destroyed. In March 1879 Father Jean-Marie-Joseph Lestanc, who was wintering with the Métis at Red Deer Forks, reported: “All the tribes – that is the Sioux, Blackfoot, Bloods, Sarcees, Assiniboines, Stoneys, Crees and Saulteaux – now form but one party. . . . Big Bear, up to this time, cannot be accused of uttering a single objectionable word, but the fact of his being the head and soul of all our Canadian plains Indians leaves room for conjecture. . . . All are in great want. . . . [They] consider the treaties . . . are of no value . . . .” Superintendent Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier* of the NWMP rode to the forks to investigate and reported that nothing had come of the gathering. However, several thousand Indians and Métis did spend a hard winter there and it is possible that Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank], Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika], and perhaps even Gabriel Dumont consulted with Big Bear and the disillusioned warriors who were continually joining his band; if cooperation between these traditional enemies had resulted, it would have been an event unprecedented in western Indian history.

Edgar Dewdney*, Sir John A. Macdonald*’s new Indian commissioner, arrived at Fort Walsh in June 1879. Big Bear could not confront him with a united Indian front but did speak with him for several days about the vanishing buffalo and the inadequate treaties. Because of their destitution, however, Little Pine signed the treaty on behalf of 472 people on 2 July and was immediately paid treaty money and given rations; Big Bear still refused. He moved south into Montana where most of Canada’s treaty Indians, with Dewdney’s encouragement, soon joined him, and where along with the American Indians they hunted the last of the buffalo. By 1882 these too were gone and the treaty Indians began returning north to petition the government for food. Big Bear’s band tried fishing at Cypress Lake (Sask.) and eating gophers, but it was hopeless. On 8 Dec. 1882 Big Bear signed Treaty no.6 at Fort Walsh so that the police would give his people food. His personal following then numbered 247.

Big Bear said his people wanted their reservation near Fort Pitt, and in July 1883 his band moved north at the government’s expense. He spent that summer visiting his old friends on their small reserves along the North Saskatchewan. All were destitute: agriculture, their only activity, was either non-existent or pathetic. That fall Big Bear began to harass the government in a new way by changing his mind about where he wanted his reserve. A series of visits, by Indian Department officials Hayter Reed* and Dewdney, and by the deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs, Lawrence Vankoughnet, from Ottawa, simply confirmed him in his stubbornness, and when his rations were cut off because of it the band freighted for the HBC while he sent messages to all the Cree chiefs to join him in a united Indian council to work for one large Indian reserve on the North Saskatchewan. To accomplish this, the Saskatchewan Herald reported that Big Bear “has made up his mind to go to Ottawa . . . if there is a head to the [Indian] Department he is bound to find him, for he will deal with no one else.” By April 1884 Big Bear and his band, swollen to about 500, began moving toward Battleford and by 16 June well over 2,000 Indians from the Saskatchewan reserves were gathered at the reserve of Poundmaker [Pītikwahanapiwīyin] for a Thirst Dance given by Big Bear; it was the largest united effort ever made by the Plains Cree.

Thirst Dances were expressly forbidden by the government; in any case the government did not allow rations to Indians off their reserves. However, Big Bear’s dance proceeded and during the celebration Kāwīcitwemot, a young warrior, beat John Craig, the farm instructor of the Little Pine reserve, when the latter abused him and refused to give him food. Craig called the police and Crozier arrived from Battleford with about 90 men. Crozier was incensed at Craig’s “indiscretion,” but since the police had been called, it was necessary that they arrest the culprit. When the police and some 400 armed, furious warriors faced each other, a single shot would have plunged the northwest into an Indian war. The police managed to haul Kāwīcitwemot from among his fellows while Big Bear, Little Pine, and Poundmaker prevented violence by shouting, “Peace, Peace!”; later the police placated the warriors to an extent by handing out large food supplies. Face had been saved all around, but as Crozier reported to Dewdney, “it is yet incomprehensible to me how some one did not fire . . . .” Unless the department could “keep their confidence . . . there is only one other [policy] – and that is to fight them.”

Big Bear did not want to fight Canada; he knew that in such a battle, as Crozier wrote with heavy irony, “the country no doubt would get rid of the Indians and all troublesome questions in connection with them in a comparatively short time . . . .” Big Bear’s demands are clearly presented in the rough English notes made of two speeches he gave to chiefs at Duck Lake (Sask.) and at Carlton in August 1884. First, he argued that the treaty they signed had been changed by Ottawa: “half the sweet things were taken out and lots of sour things left in.” A new treaty with a new reserve concept was necessary. Secondly, the Indians needed one representative from all the tribes to speak for them. “The choice of our representative ought to be given to us every four years.” He concluded: “Crowfoot is working for the same thing as I am.”

All summer Big Bear carried this message for a united stand against the government; on 17 August he met Louis Riel in Prince Albert (Sask.). They had met in Montana earlier apparently without result, but this meeting disturbed Dewdney more than any gathering of Indians. Hayter Reed was ordered to investigate the Indian complaints and when his incredibly complacent report was at last forwarded to Vankoughnet in Ottawa the latter reminded Dewdney on 4 Feb. 1885 that the Indians “have really received very much more than the Govt. was under the Treaty bound to give them.”

Such official complacency destroyed Big Bear’s last attempts at negotiated change: during that winter, 1884–85, the warrior society – those men who retold their old coup stories every night but who had fought no enemy nor so much as run a buffalo in four years – gradually separated themselves from the old chief. The band was camped with the Wood Crees at Frog Lake (Alta), 50 miles north of Fort Pitt, when the news arrived that the Métis had routed Crozier at Duck Lake on 26 March. On 2 April Big Bear’s men, led by his son Āyimisīs (Little Bad Man) and the war chief Wandering Spirit [Kapapamahchakwew] burst into the Maundy Thursday service in the Frog Lake Catholic church and forced all the unarmed whites of the settlement outside. Wandering Spirit began by shooting Indian agent Thomas Trueman Quinn; Big Bear rushed forward shouting, “Stop, stop!” But there was no stopping the men, warriors once again. Nine men, including the two Oblate priests [see Léon-Adélard Fafard] were killed; only two white women and William Bleasdell Cameron*, the HBC clerk who was protected by the Cree wife of trader James Kay Simpson, escaped. When Simpson returned that evening from a trading trip to Pitt, he found the settlement destroyed and the warriors dancing the Scalp Dance. Later, at Big Bear’s trial, Simpson reported the conversation he had had with his friend of 40 years: “now this affair . . . will be all on you, carried on your back.” The old chief answered: “it is not my doings, and the young men won’t listen, and I am very sorry for what has been done.”

When news of Frog Lake spread, the name Big Bear became synonymous with “bloodthirsty killer,” but in fact Āyimisīs and Wandering Spirit were now the band leaders. On 13 April they surrounded Fort Pitt with 250 warriors, and sent an ultimatum to NWMP Inspector Francis Jeffrey Dickens that, unless the civilians surrendered and the police left, they would attack. Big Bear wrote a note to an old acquaintance, Sergeant J. A. Martin: “Try and get away before the afternoon, as the young men are all wild and hard to keep in hand.” On 14 April, hopelessly outnumbered, Dickens and his 25 men retreated by river to Battleford while the 28 civilians led by HBC trader William John McLean* and his family surrendered to the Indians. The warriors then pillaged and burned the empty fort.

From testimony given by McLean at Big Bear’s trial, it is clear that the old chief did his best to protect the captives in camp but he was an outcast; later, when asked how Āyimisīs had treated Big Bear, McLean replied, “With utter contempt.” Without him, however, the warriors demonstrated no wider strategy than simply local pillage; they made no attempt to join Poundmaker in his attack on Battleford or Riel at Batoche. Finally, Major-General Thomas Bland Strange* and his Canadian troops arrived at Fort Pitt and on 28 May they attacked Wandering Spirit’s strong position on a hill north of Frenchman Butte. Strange was repulsed but the Indians retreated as well; during the battle Big Bear remained in the rear with the captives and women. However, a story current to this day on the Poundmaker Reserve recounts that when Samuel Benfield Steele*’s scouts attacked and routed Big Bear’s followers at Loon Lake Narrows on 3 June, Big Bear walked between the attacking police and the fleeing Cree with his “bear’s claw [that] rested in the hollow of his throat. As long as he wore that claw there, nothing could hurt him. . . . It was as if he placed an invisible wall between his people and the soldiers.”

After Loon Lake the band further scattered before General Frederick Dobson Middleton*’s advancing soldiers, victorious over the Métis at Batoche on 12 May. Kāwīcitwemot had been killed at Frenchman Butte; Āyimisīs fled to Montana; Wandering Spirit surrendered and in November 1885 he and five others of Big Bear’s band were hanged for their part in the Frog Lake killings. Big Bear slipped past all the soldiers looking for him and gave himself up to a startled policeman at Fort Carlton on 2 July 1885.

Big Bear and 14 of his band were transported to Regina, and his trial before Judge Hugh Richardson* and a jury of six on a charge of treason-felony began on 11 Sept. 1885. Poundmaker had already been convicted of the same charge – intending to levy war against the queen – and, though evidence was provided that the old chief had taken no part in the fighting and had tried to prevent bloodshed, Richardson made it clear to the jury that a claim for innocence could only be made if Big Bear had actually left his band when it “rose in insurrection.” Since there was no question of that, within 15 minutes the jury brought in a sentence of “Guilty with a recommendation to mercy.” On 25 September, Richardson sentenced him to three years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary. Just before the sentencing, Big Bear made one last speech for his people: “‘Many of my band are hiding in the woods, paralyzed with terror. . . . I plead again,’ he cried, stretching forth his hands, ‘to you, the chiefs of the white men’s laws, for pity and help to the outcasts of my band!’” The court record of the speech cannot be located; only Cameron, a witness at the trial, mentions it.

At Stony Mountain Big Bear was taught carpentry; in July 1886, perhaps because of Poundmaker’s death at Blackfoot Crossing (Alta), he was baptized. Crowfoot and other chiefs not involved in the rebellion petitioned Dewdney several times for Big Bear’s release, and in February 1887 the prison doctor reported that “Convict No. 103 [Big Bear] . . . is getting worse. He is weak and shows signs of great debility by fainting spells which are growing more frequent . . . .” As a result, on 4 March 1887, he was released. Those of his band still in Canada had been scattered among various reserves, and so he returned to the Poundmaker Reserve on 8 March. He died there on 17 Jan. 1888, perhaps from the final mortifying effects of prison and purposelessness. The Indian agent wrote of his death, “He has had domestic troubles lately, his wife preferring the society of other men. She would leave the Reserve and the old veteran would follow her for days, until he overdid himself.” He was buried in the Roman Catholic cemetery on the Poundmaker Reserve, roughly on the site of his last Thirst Dance.

Big Bear was a traditional chief, chosen and followed by the Plains Cree because of his wisdom rather than because he was acknowledged by trader or missionary or government official for his cooperation. For him the land, the water, the air, and the buffalo were gifts from the Great Spirit to all mankind; everyone might use them, but in no sense could one person own them or forbid their use to others. He saw white civilization as humiliatingly destructive of Indian civilization, but he resisted whites with ideas, not useless guns. He was the last of the great chiefs to try to unite the North American peoples against European invasion, and to that end he wanted a new treaty: one huge reserve for all Plains Indians. If his young men had not followed Riel’s example, perhaps he could have persuaded other Plains chiefs that his way was their only hope.

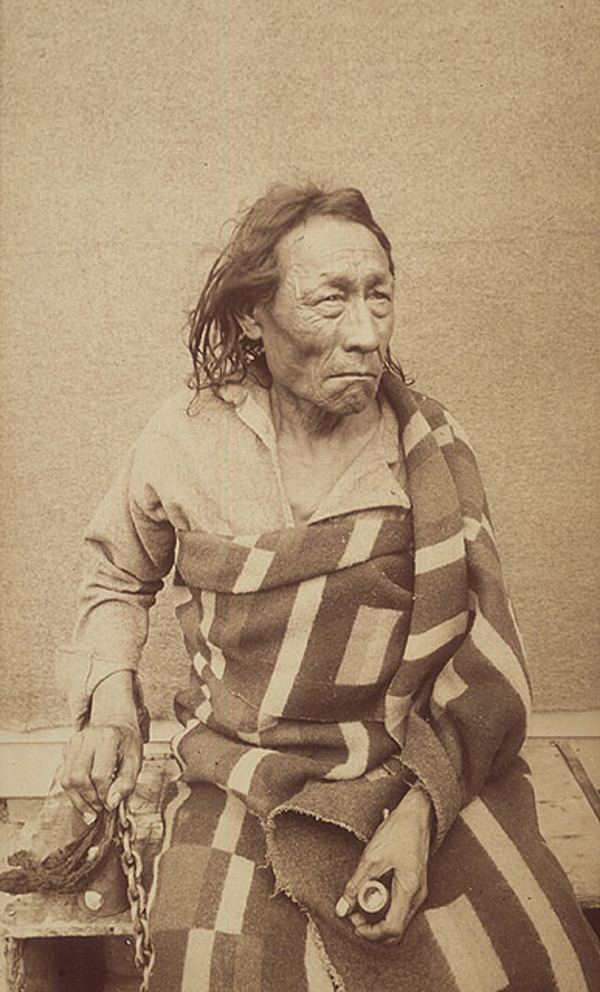

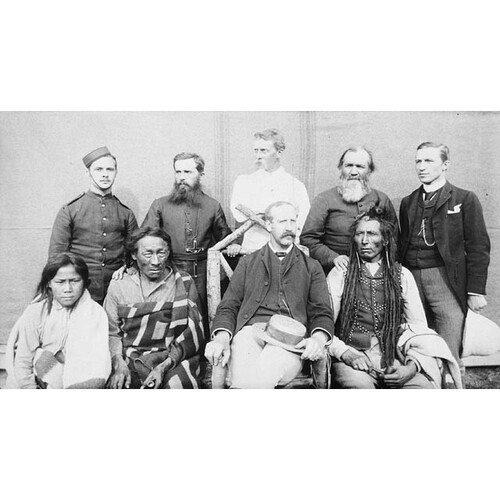

The penitentiary records list Big Bear as 5’ 5 1/4” tall; photographs reveal him to be stocky, with a strong, craggy face. John George Donkin in his book Trooper and redskin . . . described him as “a little shrivelled-up piece of humanity . . . his cunning face seamed and wrinkled like crumpled parchment.” Yet Cameron, when referring to Big Bear, corroborated Dewdney’s evaluation of his independent personality and wrote: “Big Bear had great natural gifts. . . . Had [he] been a white man and educated, he would have made a great lawyer or a great statesman. . . . [He was] imperious, outspoken, fearless.” He was indeed a great statesman, but not in the white tradition.

PAC, RG 10, B3, 3576; 3692; 3697, file 15423; RG 13, B2, 804–25. PAM, MG 12, B1, Corr., nos.901, 1136. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1882, V, no.6; 1886, XIII, no.52. J. G. Donkin, Trooper and redskin in the far north-west: recollections of life in the North-West Mounted Police, Canada, 1884–1888 (London, 1889; repr. Toronto, 1973). C. A. Messiter, Sport and adventure among the North American Indians (London, 1890). Morris, Treaties of Canada with the Indians. C. P. [Mulvany], The history of the North-West rebellion of 1885 . . . (Toronto, 1885; repr. 1971). Settlers and rebels: being the official reports to parliament of the activities of the Royal North-West Mounted Police force from 1882–1885 (Toronto, 1973). Edmonton Bulletin, 2 May 1885. Lethbridge Herald (Lethbridge, Alta.), 7 Jan. 1909. Lethbridge News (Lethbridge), 30 April 1890. Saskatchewan Herald (Battleford, [Sask.]), 18 Nov. 1878, 24 March 1879, 8 March 1884, 15 June 1885. W. B. Cameron, Blood red the sun (rev. ed., Calgary, 1950), 214–15. H. A. Dempsey, Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet (Edmonton, 1972); Jerry Potts, plainsman (Calgary, 1966). W. B. Fraser, “Big Bear, Indian patriot,” Historical essays on the prairie provinces, ed. Donald Swainson (Toronto, 1970), 71–88. Constance Kerr Sissons, John Kerr (Toronto, 1946). Stanley, Birth of western Canada; Louis Riel. Rudy Wiebe, The temptations of Big Bear (Toronto, 1973). R. S. Allen, “Big Bear,” Saskatchewan Hist. (Saskatoon), 25 (1972): 1–17. Maria Campbell, “She who knows the truth of Big Bear: history calls him traitor, but history sometimes lies,” Maclean’s (Toronto), 88 (1975), no.9: 46–50. D. G. Mandelbaum, “The Plains Cree,” American Museum of Natural Hist., Anthropological Papers (New York), 37 (1941): 155–316. Rudy Wiebe, “All that’s left of Big Bear: in a small bag, in a small room in New York City, the great spirit rests,” Maclean’s, 88 (1975), no.9: 52–55.

Cite This Article

Rudy Wiebe, “MISTAHIMASKWA (Big Bear, Gros Ours),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mistahimaskwa_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mistahimaskwa_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Rudy Wiebe |

| Title of Article: | MISTAHIMASKWA (Big Bear, Gros Ours) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |