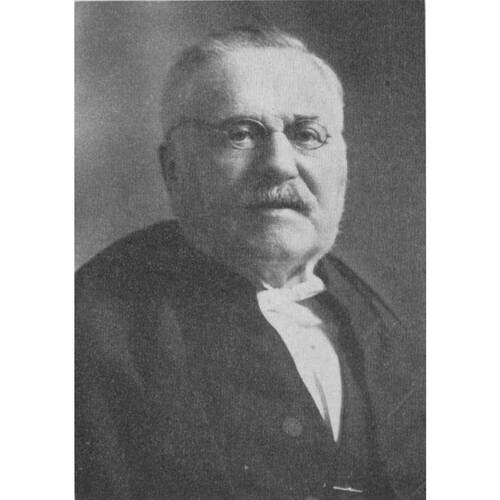

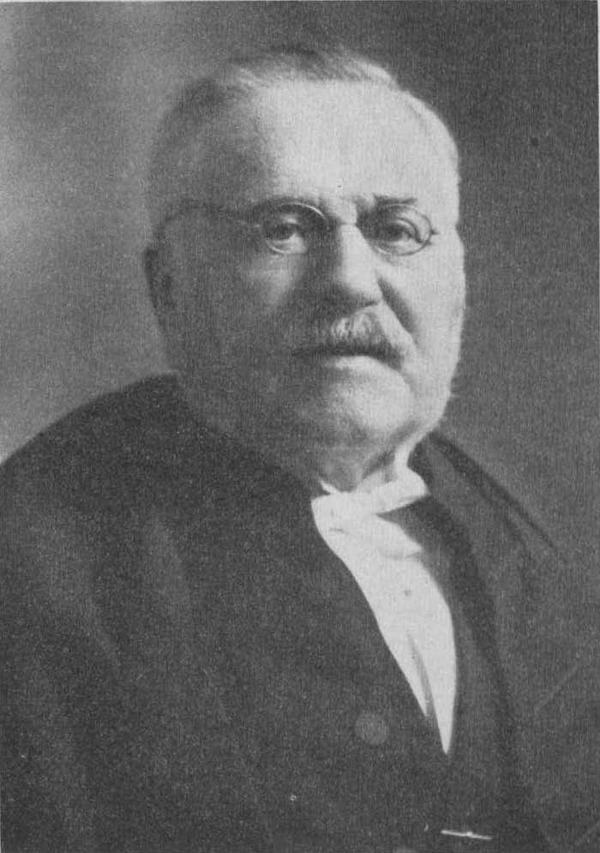

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

RICHARDSON, HUGH, lawyer, office holder, militia officer, and judge; b. 21 July 1826 in London, England, son of Richard Richardson and Elizabeth Sarah Miller; m. first Charlotte Isabella — (d. 1879), and they had two sons and four daughters; m. secondly 2 April 1883, in Drumbo, Ont., Rachel Louisa Piper, née Hughson (d. 1904); d. 15 July 1913 in Ottawa.

Hugh Richardson immigrated with his family to York (Toronto) in August 1831, and in 1835 his father became the first manager of the London branch of the Bank of Upper Canada. Educated at the London District Grammar School, Hugh was admitted to Osgoode Hall as a student in 1842 and read law with John Wilson*. He was called to the bar in November 1847 and subsequently practised in Woodstock until 1872, serving also as crown attorney for Oxford County from 1856 to 1862.

As was common for professional men of the era, Richardson was active in the local militia. He helped to organize the 22nd Battalion Volunteer Militia Rifles (Oxford Rifles) in 1862 and would become commander of the unit in April 1866. In 1865, with the rank of major, he saw service at La Prairie, Lower Canada, under Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley. Later, during the Fenian raids of 1866 in Upper Canada [see John O’Neill*], he was the lieutenant-colonel (his highest rank) commanding at Sarnia.

By order in council in June 1872 Richardson was appointed chief clerk of the Department of Justice in Ottawa. Four years afterwards, on 22 July 1876, he became one of the stipendiary magistrates for the North-West Territories, joining Matthew Ryan and James Farquharson Macleod*. That fall he travelled to the North-West, and the next year he returned to Ottawa to get his family. On 27 Sept. 1877 he arrived with his invalid wife and three daughters at Battleford (Sask.), the seat of the territorial government, where he had had a large house built.

Shortly after arrival, one of his daughters fell in love with a North-West Mounted Police subconstable named Elliott. In February 1878 the latter took her by force from the Richardson home and married her before a Presbyterian minister. The parents quickly got her back again, and Richardson laid several complaints against Elliott and his three collaborators for abducting his underage daughter. In an unusual display of frontier justice, he later presided over Elliott’s trial, but the young policeman was acquitted by the jury. Shortly afterwards, Richardson’s wife and mother died on the same day.

Richardson lived in Battleford until 1883, when, following his remarriage, he moved with the territorial government to Regina. Besides holding trials throughout the territories, he served as legal adviser to the lieutenant governor, and, like his fellow stipendiary magistrates, he was an ex officio member of the territorial council until that body was abolished in 1888. Richardson thus played a major, perhaps the major, role in drafting the territory’s ordinances, a task that in most cases meant adapting Ontario legislation to the needs of the frontier.

Best known for presiding over the trial of Louis Riel* at Regina from 20 July to 1 Aug. 1885, Richardson also held a large number of other trials resulting from the North-West rebellion. In addition to many of Riel’s Métis followers (among whom was Maxime Lépine*), the defendants included the prominent chiefs Poundmaker [Pītikwahanapiwīyin*], Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa*], and One Arrow [Kāpeyakwāskonam*]. Two white men also appeared before him: Riel’s “secretary,” William Henry Jackson*, and the only putative “white rebel” other than Jackson who could be found, Thomas Scott.

Richardson’s handling of these controversial trials has stood up fairly well to the exacting scrutiny of modern historians. He gave Riel considerable latitude to speak in his own defence, not only at the end but even during the course of the trial. Once the jury found Riel guilty, Richardson had no choice under the law except to impose the death penalty, although he might be faulted for gratuitously commenting that he could not offer Riel any hope of a pardon. Some of Richardson’s rulings in the lesser trials have been criticized as erratic, but no one has alleged a consistent pattern of bias either for or against the defendants. In fact, after the legal proceedings had run their course, Oblate missionary Alexis André* wrote to Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché*: “Judge Richardson is certainly a just and impartial man and I bear him witness that I would much rather see our people judged by him than by Judge [Charles-Borromée Rouleau*] who is a vindictive man and a servile instrument in the hands of the government.” (Rouleau, one of Richardson’s colleagues as stipendiary magistrate, presided at the rebellion trials in Battleford, where he sentenced eight Indians to be hanged for murder.)

After the excitement and publicity of the rebellion trials, Richardson returned to his normal routine of judicial work and legislative drafting, and in 1887 he was appointed senior judge on the newly created Supreme Court of the North-West Territories. His responsibilities were equivalent to those of a chief justice and included supervising the administrative work of the court and presiding when the members sat en banc. Each member also had his own judicial district, Richardson’s being Western Assiniboia. This arrangement reduced his travelling because Western Assiniboia included Regina.

He and two colleagues on the Supreme Court were also appointed “legal experts” – an office that, until its abolition on 30 Sept. 1891, made them non-voting members of the territory’s assembly. With or without the title, Richardson played the leading role in drafting the 1888 and 1898 consolidations of the territorial ordinances. He was also administrator (acting lieutenant governor) of the territories in 1897 and again in 1898.

When parliament created the office of chief justice of the Supreme Court of the North-West Territories, Richardson probably expected the appointment; however, he was passed over in February 1902 in favour of his junior colleague Thomas Horace McGuire. That summer, although he was 76 years old, Richardson travelled from Edmonton to Fort Chipewyan (Alta) on Lake Athabasca as part of the commission paying treaty money in the Treaty No.8 region. He then retired in November 1903 and returned to spend his final years in Ottawa, a city that was also the home of one of his daughters, the wife of Donald Alexander Macdonald.

Richardson typifies a generation of Ontario lawyers, politicians, and civil servants who moved to the prairies in mid life and endured the hardships of the frontier while they transplanted the legal, political, and administrative institutions of Canadian society. With the benefit of hindsight, historians have criticized some of his judicial decisions and legislative advice, but his competence and conscientious dedication remain unquestioned.

AO, F 23. GA, M477, items 1064, 1269–71; M5908, item 1676. Law Soc. of Upper Canada Arch. (Toronto), 1-1 (Convocation, minutes). London Public Library and Art Museum (London, Ont.), St Thomas, Ont., cemetery transcriptions. NA, MG 27, I, C4, 5; I18; MG 29, D61; MG 30, D1, 25: 753–60. PAA, 69.305/177 (1893). PAM, MG 3, D1. Saskatchewan Arch. Board (Regina), R-85 (Hugh Richardson papers). Ottawa Citizen, 16 July 1913. Ottawa Evening Journal, 16 July 1913. Regina Leader, 30 March 1904. Regina Standard, 26 Nov. 1903. Saskatchewan Herald (Battleford), 10 Feb. 1879. Bob Beal and R. [C.] Macleod, Prairie fire: the 1885 North-West rebellion (Edmonton, 1984), 292–333. W. F. Bowker, “Stipendiary magistrates and the Supreme Court of the North-West Territories, 1876–1907,” Alberta Law Rev. (Edmonton), 26 (1987–88): 245–86. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1886, no.52. S. E. [Estlin] Bingaman, “The North-West rebellion trials, 1885”

Cite This Article

Thomas Flanagan, “RICHARDSON, HUGH (1826-1913),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_hugh_1826_1913_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_hugh_1826_1913_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Thomas Flanagan |

| Title of Article: | RICHARDSON, HUGH (1826-1913) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |