Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

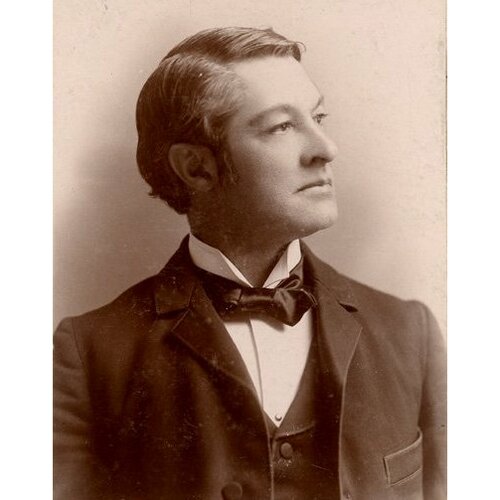

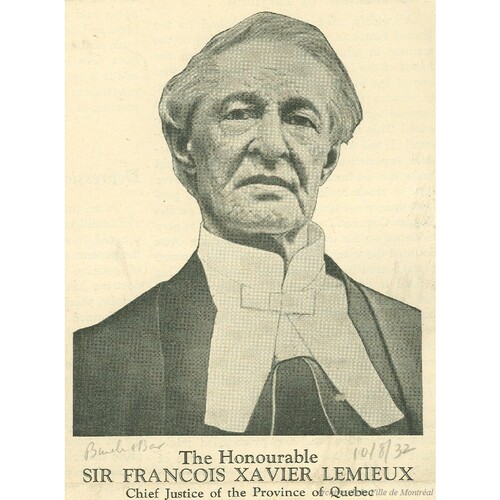

Lemieux, Sir François-Xavier (baptized François-Xavier-Ferdinand), lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 9 April 1851 in Saint-Joseph-de-la-Pointe-Lévy (Lévis), Lower Canada, son of Antoine Lemieux, a farmer, and Henriette Lagueux; m. 4 Feb. 1874 Marie-Aurélie-Diane Plamondon (d. 14 Jan. 1933) in the parish of Notre-Dame de Québec, and they had 12 children; d. 18 July 1933 in the parish of Saint-Cœur-de-Marie, Que., and was buried three days later in Notre-Dame de Belmont cemetery in Sainte-Foy (Quebec City).

François-Xavier Lemieux was a descendant of the old Lemieux family who had settled in Pointe-Lévy (Lévis) in the middle of the 17th century. At his baptism he was given the two first names of his uncle and godfather, François-Xavier Lemieux* (often called simply François). A lawyer and politician from Lévis who died a bachelor in 1864, he met the cost of his nephew’s education. After attending the local school, the Collège de Lévis (1861–64), and the Séminaire de Québec (1864–69), young Lemieux studied law at the Université Laval in Quebec City (1869–72) and became an articled clerk in the office of Gilbert Larue. After obtaining his llb, he was called to the bar of the province of Quebec on 24 July 1872. He subsequently practised in Quebec City and proved to be a talented criminal lawyer; in 1878, for example, he defended George Bartley, who was suspected of murdering Sergeant Lazare Doré, and secured an acquittal.

During his legal studies Lemieux acquired public debating skills through his participation in a university parliament, which was a type of model assembly. Following in the footsteps of his deceased uncle and influenced by his father-in-law, Marc-Aurèle Plamondon*, he then became politically engaged with the provincial Liberal Party. He was a constant presence in Quebec Liberal circles, and in the spring of 1880 he took part in founding the Club de Réforme – the Liberal coterie on Rue de la Fabrique (Côte de la Fabrique), which ceased to be active in 1882 – and its organ Le Libéral. L’Électeur, whose pronounced “Rouge” bias would incur the wrath of the episcopate, and Le Soleil, which adopted a moderate tone while remaining the official newspaper of the Liberal Party, became successors of Le Libéral in 1880 and 1896 respectively.

In the provincial election of 1878 Lemieux made his formal political debut as a Liberal Party candidate in Bonaventure. The political climate at the time favoured the Liberals, the church itself having established, through the voice of the papal delegate George Conroy*, the difference between doctrinaire liberalism, some aspects of which ran counter to Roman Catholic doctrine, and political liberalism, which claimed to be simply reformist. Lemieux, therefore, had high hopes of winning the election, but he ran against Joseph-Israël Tarte*, a formidable Conservative and ultramontane. Defeated, he again tried his luck in 1882, this time at the federal level in the riding of Beauce. His opponent was Joseph Bolduc, a native of Beauce, who had a strong social commitment to the region and had been a Conservative mp since 1876. Lemieux suffered another defeat.

Thinking that his chances were better in his native region, he stood as a candidate there in an 1883 provincial by-election against Joseph-Edmond Roy*. This worthy adversary belonged to an old Lévis family who wielded considerable influence in the Conservative Party. Lemieux built his electoral platform on the shaky ground of opposition grievances. He attacked the Conservative government and Premier Joseph-Alfred Mousseau*. Lemieux did not consider him sufficiently aggressive or authoritative to run a province that was in a state of crisis following the political wheeling and dealing resulting from the sale of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway by the government of Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*. The transaction had even been a source of discontent in the Conservative Party. Because the deal favoured Montreal, public opinion was particularly aroused in the regions of Trois-Rivières and Quebec City. Against this backdrop the Castors faction [see Louis-Adélard Senécal*; François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel*] formed in the Conservative Party; its adherents objected to disposing of what was considered an asset for Quebec. Compromised, Chapleau had to leave the provincial government in 1882. Mousseau then became premier, a change that did not improve the situation. The Castors made life difficult for Mousseau and his government. In these circumstances Lemieux employed political strategy to make the most of the internal strife and the fissures within the Conservative Party. By bringing together to his benefit the votes of the Liberals and the Castors, who were gnawing away at and dividing the Mousseau government, he won against Roy with a majority of 36 votes. La Patrie of 17 Nov. 1883 declared: “Today, he has the honour of winning a glorious victory worth hundreds of those that he should have won in Bonaventure and Beauce. By having waited, he has gained a great deal.”

A victory more than a triumph, the entry of Lemieux into the Legislative Assembly nevertheless had far-reaching political ramifications: it revealed that Mousseau no longer had the full confidence of his party. As L’Électeur of 17 November reported, “It must be admitted that the defeat of Mr Roy has struck a mortal blow to the government, which was fully counting on winning easily in Lévis and getting its candidate elected there without difficulty.” Bowing to pressure, Mousseau abandoned politics in January 1884 to become a Superior Court judge and left the responsibility of restoring the government’s image to John Jones Ross*, a right-wing Conservative. After his victory Lemieux was invited by the head of the federal Liberal Party, Edward Blake*, to enter the House of Commons. He had no intention of leaving the provincial arena, however, and earned a second term in the general election of 1886, again defeating Roy.

Meanwhile, in 1885 Lemieux had served as the French-speaking criminal lawyer who, along with James Naismith Greenshields and Charles Fitzpatrick*, defended Louis Riel* against the charge of high treason. The choice of Lemieux can be explained by his family connection with Jean-Baptiste-Romuald Fiset (the two men’s wives were cousins), an old classmate and personal friend of Riel. Fiset served as the link between the Association Nationale pour la Défense des Prisonniers Métis and the accused. Furthermore, Lemieux had to his credit major successes at the Quebec assize courts and was known to enjoy widely publicized challenges and causes. He had just scored a great win in saving Louis Sougraine from the gallows without calling a single witness, playing solely on the feelings and passions of the jury, an affair to which Pamphile Le May* devoted a novel in 1884.

During Riel’s trial Lemieux wrote to his wife from Regina: “We saw the famous Louis Riel a moment ago.… Meeting the man, a prisoner of the state, and one who has played such an important part in his country, was a solemn business.” Riel’s lawyers pleaded insanity, which the accused’s bearing in the trial could have validated, but on 1 Aug. 1885 the jury rendered a verdict of guilty. Judge Hugh Richardson* pronounced the death sentence and Riel was hanged on 16 November. According to Lemieux, the case had been decided before the trial had even begun. By participating in one of the most famous legal cases in Canadian history, Lemieux had, however, won favour with Honoré Mercier* and the national Liberal Party [see Sir Wilfrid Laurier*] and acquired prestige in Quebec, a province whose sympathy lay with Riel at the time.

Despite Lemieux’s expectations, Mercier, who was sworn in as premier of the province of Quebec on 29 Jan. 1887, did not name him a minister. Ideologically, the two men were not in complete agreement. Mercier displayed a strong penchant for provincial autonomy: he questioned the spirit of confederation and deplored the federal government’s centralist policy. In 1887 he even convened an interprovincial conference in Quebec City, the first in the history of the country since confederation, to study these issues. For his part Lemieux remained a true Liberal, cut from the same cloth as Laurier. He was not inclined to grumble about federal supervision or the paternalism of some Montreal mps.

In 1890 Lemieux stood again in Lévis, this time against Angus Baker, a little-known Conservative. He was elected, but was not included in Mercier’s cabinet. Disappointed, he distanced himself from the nationalist group and refused to run in the election of March 1892, which was triggered by the dismissal, on 16 Dec. 1891, of Mercier, who had been compromised in the Baie des Chaleurs Railway scandal. By a surprising coincidence, the trio of Greenshields, Fitzpatrick, and Lemieux was reassembled. Lemieux defended Mercier, who was exonerated from any conspiracy. The latter thanked his lawyer with these words: “You have been eloquent and skilful, but above all, you have been a true friend.” Mercier emerged from the trial an aged and broken man; he died prematurely on 30 Oct. 1894. Lemieux was then asked to succeed Mercier in Bonaventure. He hesitated, having disassociated himself from the nationalist Liberals in 1892, but he gave in and was successful in the by-election of December 1894. In the provincial election of May 1897, he took Bonaventure and Lévis. Despite this double victory, he resigned as an mla following his appointment as a judge of the Superior Court for the district of Arthabaska on 13 Nov. 1897.

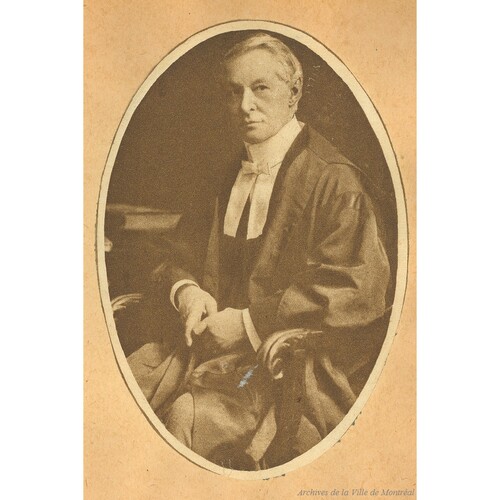

Although Lemieux’s political career had probably not measured up to his ambitions, his legal career, which included defending Louis Riel and Honoré Mercier, was much more rewarding. As Tarte noted in 1892, “The list of those he saved from prison or from the scaffold is a long one!” Lemieux was elected bâtonnier of the judicial district of Quebec City in 1896 and 1897, and bâtonnier général for the province of Quebec in 1897. As a Superior Court judge, he succeeded his father-in-law, who retired at Laurier’s request. Lemieux was transferred to the district of Saint-François in 1898, and then to that of Quebec City in 1906. In 1911 he became deputy chief justice of the Superior Court and in 1915 he was appointed chief justice. Awarded by the Conservative government of Sir Robert Laird Borden, the prestigious nomination was indicative of the solid reputation Lemieux, a faithful Liberal, had acquired in the field of law.

At the Superior Court (the Quebec court of common law to which were referred in the first instance all disputes that did not specifically come under another court’s jurisdiction) Judge Lemieux heard cases of various types. For example, he ruled authoritatively on the legal validity of clandestine Catholic marriage, an issue much discussed in ecclesiastical and legal circles following the judicial decision of John Sprott Archibald in March 1901 [see Paul Bruchési]. In his judgement in the case of Durocher v. Degré, rendered in the Court of Revision on 17 May 1901, he stated that “if the religion we profess obliges us to have our marriage celebrated before our curé, and if it forbids us to contract the marriage before any other functionary, it is necessary that we therefore submit to these prescriptions.” Judge Lemieux also presided over several trials for murder, a crime that at the time was subject to the death penalty. He put his legal expertise at the service of the temperance cause, to which he devoted a book published in 1910, as well as articles and lectures.

Lemieux was awarded honours and held prestigious offices. He earned two honorary llds, one from the Université Laval in June 1900 and the other from Bishop’s College in Lennoxville (Sherbrooke) in May 1929. He was appointed a member of the Council for Public Instruction in 1911, named a commander of the Order of St Gregory the Great in June 1914, and knighted by King George V in January the following year. In 1925 and 1927 he acted as administrator of the province of Quebec during the term of Lieutenant Governor Narcisse Pérodeau.

Justice Sir François-Xavier Lemieux died in office on 18 July 1933. He distinguished himself more as a criminal lawyer than as a politician before acceding to the judiciary, where he excelled in carrying out a noble task, impelled by passion and a work ethic that his lack of success in politics had not shaken.

In his capacity as a judge, François-Xavier Lemieux left several writings, including Le mariage clandestin des catholiques devant la loi du pays … (Montréal, 1901), which he published in collaboration with É.‑J. Auclair. To the temperance cause he dedicated the following: Sobre et riche (Québec, 1910); the speech entitled “L’alcool et les annales judiciaires,” which was published in Premier congrès de tempérance du diocèse de Québec, 1910: compte rendu (Québec, 1911): 212–22; and various articles, including “Un fait historique,” La Rev. populaire (Montréal), 5 (1912), no.6: 126.

BANQ-Q, CE301-S1, 4 févr. 1874; 16 janv., 21 juill. 1933; CE301-S19, 11 avril 1851; P145. Private arch., Andrée Désilets (Sherbrooke, Québec), Fonds M.‑A. Plamondon et F.‑X. Lemieux, Corr., discours et coupures de journaux. Le Devoir, 18, 21 juill. 1933. Le Monde illustré (Montréal), 17 juill. 1897. Andrée Désilets, “Une figure politique du XIXe siècle, François-Xavier Lemieux,” RHAF, 20 (1966–67): 572–99; 21 (1967–68): 243–67; 22 (1968–69): 223–55; “Une figure politique du XIXe siècle, François-Xavier Lemieux” (mémoire de d.e.s., univ. Laval, 1964). Lorraine Gadoury and Antonio Lechasseur, Persons sentenced to death in Canada, 1867–1976: an inventory of case files in the fonds of the Department of Justice ([Ottawa], 1994). P.‑G. Roy, Les avocats de la région de Québec (Lévis, Québec, 1936 [i.e., 1937]); Les juges de la province de Québec. J.‑I. Tarte, 1892, procès Mercier: les causes qui l’ont provoqué, quelques faits pour l’histoire (Montréal, 1892).

Cite This Article

Andrée Désilets, “LEMIEUX, Sir FRANÇOIS-XAVIER (baptized François-Xavier-Ferdinand),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lemieux_francois_xavier_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lemieux_francois_xavier_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrée Désilets |

| Title of Article: | LEMIEUX, Sir FRANÇOIS-XAVIER (baptized François-Xavier-Ferdinand) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |