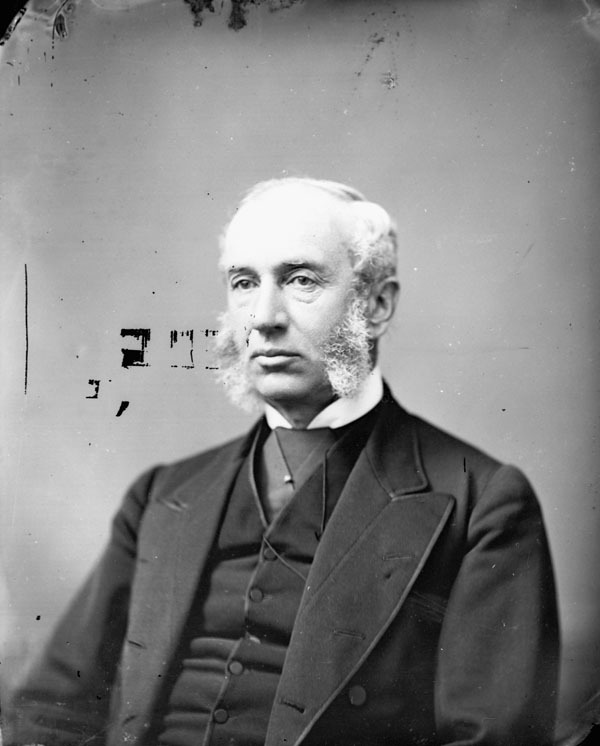

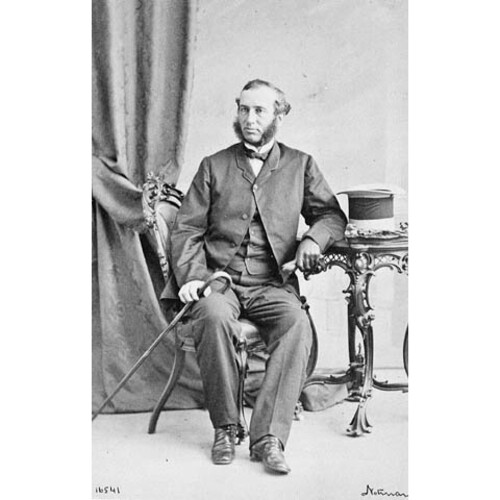

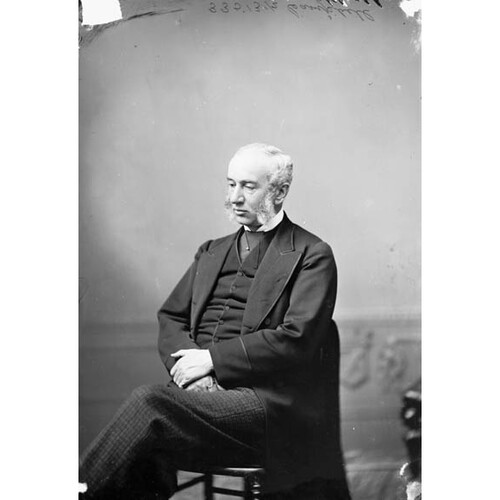

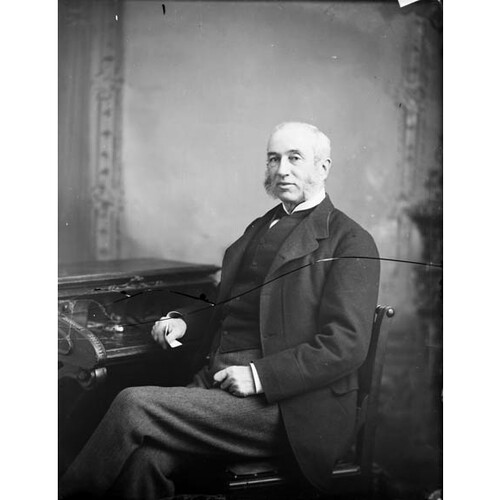

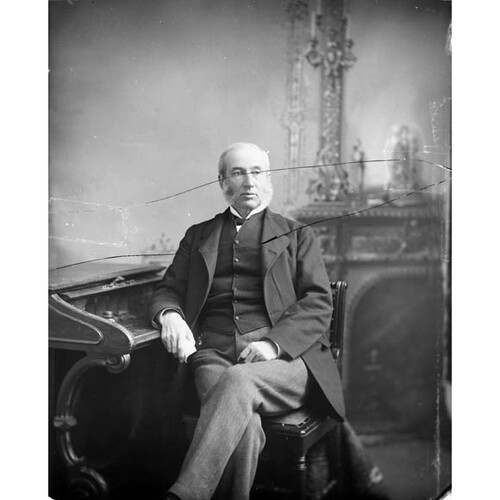

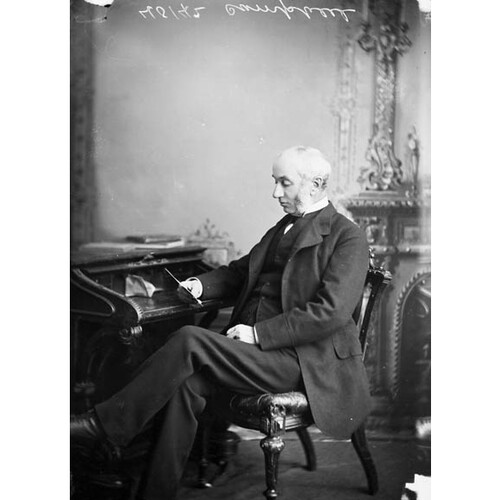

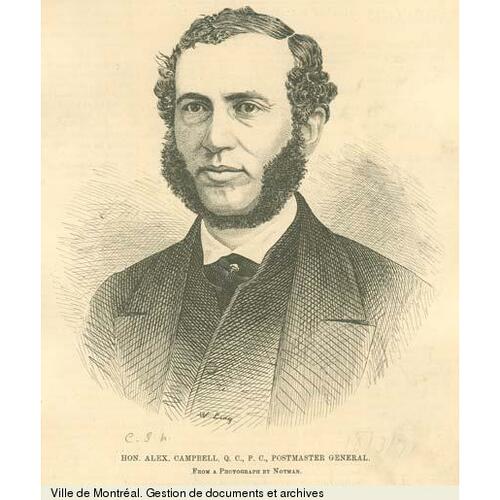

CAMPBELL, Sir ALEXANDER, lawyer, politician, educator, businessman, and office holder; baptized 9 March 1822 in Hedon, England, son of James Campbell and Lavinia Scatcherd; m. 17 Jan. 1855 Georgina Fredrica Locke Sandwith in Beverley, England, and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 24 May 1892 in Toronto.

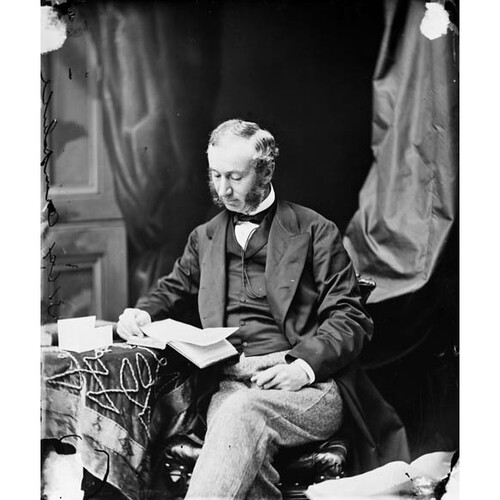

James Campbell, a physician of Scottish origin, moved to the Canadas with his family in 1823. They lived initially in Montreal, relocated in Lachine ten years later, and settled in Kingston, Upper Canada, in 1836. Alexander Campbell received an unusually good education by the standards of early-19th-century Canada. His first teacher was a Presbyterian clergyman. Though his family was Anglican, he was then sent, along with his brother Charles James, to the Roman Catholic Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe in Lower Canada, where he acquired a sufficient knowledge of French to use the language publicly in later life. He next attended the Midland District Grammar School in Kingston. From there he went to the office of Henry Cassady as a law student. Following Cassady’s death in September 1839, he then, at the age of 17, transferred his articles to John A. Macdonald. Macdonald’s first student had been Oliver Mowat*, Campbell was his second. For a brief period the three young men, all destined for illustrious careers, worked together in Macdonald’s office in Kingston. In 1843 Campbell was admitted to the bar and became Macdonald’s partner. The partnership, which in itself was not particularly important, was dissolved in 1849. What was important was the political alliance formed by these two young men in the 1840s. They would remain intimate associates until Campbell abandoned politics in 1887.

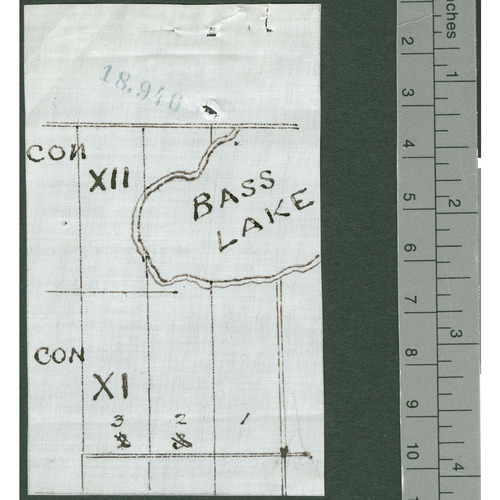

Campbell’s public career began on Kingston’s city council: from 1850 to 1852 he was an alderman, representing Victoria Ward. In 1858, and again in 1864, he was elected to the province’s Legislative Council for the Cataraqui division, a large constituency that included Kingston and all of Frontenac and Addington counties; he served as speaker of the council from February to May 1863. In late 1861, when Macdonald, now attorney general for Upper Canada, was desperately attempting to form a cabinet, he asked Campbell to take office. Campbell agreed to do so only if Thomas Clark Street* and John Hillyard Cameron*, from the old guard of tories, were included, but Macdonald did not comply. The incident would appear to indicate that Campbell’s contacts with tory factions in Toronto and western Upper Canada were better than Macdonald’s.

Perhaps the high point of Campbell’s pre-confederation career came during the crisis precipitated by the resignation on 21 March 1864 of the coalition government of John Sandfield Macdonald* and Antoine-Aimé Dorion. After Adam Johnston Fergusson* Blair failed to form a government, Governor General Lord Monck asked Campbell to try. He also failed, and with that failure went his only real opportunity to become a major political leader. On 30 March he secured ministerial rank as commissioner of crown lands in the government of Macdonald and Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché*, a position he held until 30 June 1867. As a member of this coalition cabinet, he was a delegate to the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences of 1864, and is thus a father of confederation.

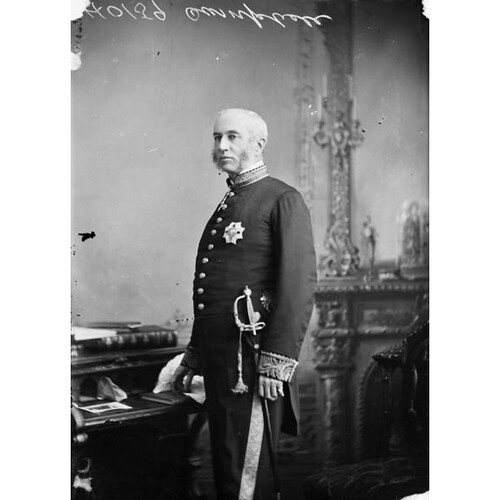

Campbell never ran for public office after 1867. He was called to the Senate on 23 October of that year and he remained in the upper chamber until 7 Feb. 1887, when he resigned. He held a wide variety of cabinet posts during those years: postmaster general on four occasions (1867–73, 1879–80, 1880–81, 1885–87), superintendent general of Indian affairs and minister of the interior (1873), receiver general (1878–79), minister of militia and defence (1880), and minister of justice and attorney general (1881–85). In addition, he was acting minister of inland revenue (1868–69) and government leader in the Senate (1867–73, 1878–87). During the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie (1873–78), Campbell led the Conservative party in the upper chamber. He had become a qc in 1856 and was created a kcmg in 1879. He represented Canada in 1887 in London at the first colonial conference, largely a ceremonial affair. On 1 June of that year he was appointed lieutenant governor of Ontario, a post he still held when he died five years later. For a brief period after his appointment, the three young men who had worked together in Kingston in 1839 constituted an amazing political constellation: Macdonald was Conservative prime minister of Canada; Mowat, who in spite of a long-time feud with Macdonald remained a friend of Campbell, was Liberal premier of Ontario; and Campbell was its lieutenant governor.

Campbell was heavily involved in activities other than politics and the practice of law. In 1861–64 he served as dean of the faculty of law at Queen’s College in Kingston. He had extensive business interests, which in the 1850s had included various railway companies, the Kingston Fire and Marine Insurance Company, and the Cataraqui Cemetery Company. Much of his business activity dates from 1873, when the first Macdonald government fell. This event placed Campbell in opposition and, until he joined Macdonald’s second government in 1878, he had substantial amounts of free time. During the 1870s he was president of the Intercolonial Express Company, which had been organized when the Intercolonial Railway was opened; vice-president of the Isolated Risk Fire Insurance Company of Canada; chairman of the board of the Toronto branch of the Consolidated Bank of Canada; and a director of the Kingston and Pembroke Railway and of the London and Canadian Loan and Agency Company. As well, he owned shares in both the Ives Mining Company and the Maritime Bank of the Dominion of Canada and was active in the Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company and in the Canadian Express Company. Early in the decade he purchased coal properties from Charles Tupper*, and in 1873, with John Beverley Robinson and Richard John Cartwright*, he bought a coal area in Nova Scotia that proved unsuccessful. During the 1880s he speculated in western Canadian land. When Campbell died he was president of two firms: the Imperial Loan and Investment Company of Canada Limited and the Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company.

Campbell had no difficulty in maintaining close business ties with such prominent Kingston Liberals as Cartwright and Charles Fuller Gildersleeve. Perhaps more dramatic was his business association with leading federal Liberals who had little to do with Kingston. As vice-president of the Isolated Risk Fire Insurance Company, Campbell was involved with prominent tories such as Matthew Crooks Cameron* but in essence the company was a Liberal operation. Alexander Mackenzie was president and the board included such other Liberal luminaries as Edward Blake*, George Brown*, Adam Crooks*, William McMaster*, and Robert Wilkes*. Kingston nevertheless remained important in all Campbell’s undertakings. Through business and politics, and through social activity and marriage, he was at the centre of a web of interrelationships among various prominent Kingston families – the Campbells, Macdonalds, Stranges, Kirkpatricks, Gildersleeves, and Cartwrights.

Campbell’s achievements as a cabinet minister were minor, but some of his administrative decisions had wide ramifications. He was minister of justice when Louis Riel* was captured in 1885. Under no circumstances did Campbell want the Métis leader tried in Winnipeg. As he explained to Macdonald, Riel “should be sent under safe guard to Regina, and there be tried before [Hugh Richardson*] and a jury of six, under the North West Territories Act,” by which a prisoner was not entitled to a mixed anglophone and francophone jury. A trial in Winnipeg, especially with some French-speaking jurymen, could easily have led to a verdict other than guilty, an outcome regarded by Campbell as a possible “miscarriage of justice.” With such a verdict Canada might have been spared the crisis surrounding Riel’s execution or experienced a quite different one.

Campbell’s decision to ensure that Riel be showed no favour exemplified his administrative style. He was cool, conscientious, conservative, legalistic, narrow, paternalistic, and frugal. In 1885 advice he gave to Macdonald pointed out the difficulties caused by “constant giving way to truculent demands[,] and our delays and the irritation and mischiefs which they produce are in everybody’s mouth, and are evils of which you and I may well take note. . . . I hope that we shall take a fresh start.”

What made Campbell an important figure was not his lengthy tenure as a cabinet minister, but his roles as a confidant who advised the prime minister in a wide variety of areas and as a political manager within the Conservative party. The latter role was central to his career: Campbell was a tory fixer who often acted as Macdonald’s legate. This was especially true during the first Macdonald government (1867–73). In those years, Campbell’s most active as a party manager, he was postmaster general for all but four months. He used the patronage component of his portfolio assiduously and in the interests of his party. Pay raises for postal workers, leaves of absence, and appointments were manipulated for partisan purposes. Consequently, though Campbell was never a major political figure, he was occasionally seen as such. In 1887 the Toronto Week noted that his appointment as postmaster general in 1867 had been a major achievement: “The new position did not call, to the same extent as the previous one [commissioner of crown lands], for the exercise of legal acumen, but it involved dealing with large public interests and a very extended patronage.”

Campbell held Macdonald responsible for the fall of the government in 1873, noting in early November that the administration could have held power had “Sir John A kept straight during the last fortnight.” His participation in the management of the 1874 general election was less than had been the case in 1872 and after the massive Conservative defeat, he became less and less involved in party management. His successor in eastern Ontario was John Graham Haggart*. During the mid 1870s Campbell was heavily involved in business activity, and after 1878 his focus was on departmental work. His managerial role can best be understood by illustrating the scope and nature of his activities around the time of the 1872 election. The illustration will also reveal much about the nature of 19th-century politics.

One of his numerous responsibilities in the election period was looking into the situation in various parts of the country. Thus early in the campaign he asked Alexander Morris*, administrator of Manitoba and the North-West Territories, for a “paper on Manitoba,” informed Macdonald that John George Bourinot* had prepared a study of the relations between Nova Scotia and Canada, and asked the prime minister to dictate a paper on the “general achievements of the government.” After consulting Henry Nathan (mp for Victoria) and Donald Alexander Smith* (mp for Selkirk), Campbell advised Macdonald to call the elections in British Columbia for the “earliest possible period” and those in Manitoba for “the last half of August or the first week of September.” Campbell assisted in securing Sir George-Étienne Cartier*’s by-election victory in September 1872 in Provencher, and, after Cartier died in May 1873, he was involved in the fight for the seat, which was won by Riel. In December 1872 Campbell had advised the prime minister on the sensitive problem of Riel and the Métis: “What do you say to my proposition to pay the loyal French half breeds the £500 recommended by Donald Smith out of the secret service fund?” In July 1873 Campbell became minister of the interior and therefore administratively concerned about Manitoba.

The raising of funds for the 1872 election became in 1873 a matter for a royal commission of inquiry into the Pacific Scandal. Called to testify, Campbell claimed only a dim knowledge of Sir Hugh Allan*’s massive campaign contributions of the previous year. Regardless of this disclaimer, and most tories suffered serious memory loss in 1873, Campbell knew much about campaign funds. In July 1872 William Cleghorn at the office in Toronto of the commissioners of the Trust and Loan Company of Canada told him that he and his staff would contribute to the election fund. Later in the campaign Campbell dealt with a remarkable incident in which Macdonald borrowed $10,000 for electoral purposes on a banknote co-signed by John Shedden* and Campbell’s brother Charles. The security, Charles told Alexander, was “‘Sir John’s undertaking in writing as a member of the Government to recoup us the amount loaned him.’” How Campbell handled the situation is uncertain, but fortunately he understood Macdonald and was able to solve the money problems, caused, in Campbell’s opinion, by the prime minister’s frequent intoxication between his election in 1872 and the defeat of his government in November 1873.

Though a senator after 1867, Campbell helped to manage the Conservative party within the House of Commons. For example, he offered Dr James Alexander Grant (mp for Russell) a senatorship in return for his loyalty during the parliamentary crisis of 1873. He was also heavily involved in the manœuvres designed to prevent the defection of D. A. Smith immediately prior to the fall of the government.

Controlling newspapers was another of the senator’s key interests. This was an important and difficult problem because in Ontario the Conservative party faced the powerful Toronto Globe, owned by George Brown. Repeated attempts were made to counter its influence, but the Conservatives were routinely unsuccessful [see James Beaty]. None the less, a press war was waged and Campbell, as long as he was postmaster general, was a central combatant. He used advertising about post-office matters to keep fractious editors loyal and insolvent newspapers alive. To obtain advertising or printing contracts from the government, a newspaper had to be on what F. Munro, an Orangeville newspaper proprietor, called in 1871 the “List.” Moreover, Campbell received numerous requests for help from newspapermen. Occasionally he acted rapidly. During the 1872 campaign James George Moylan* of the Canadian Freeman in Toronto asked for an advance on a “few thousand dollars worth of printing.” The request was granted within five days, doubtless because Moylan threatened to suspend publication in the midst of the campaign. The Ontario Workman, Ontario’s first important labour newspaper, was on Campbell’s “List”: during the 1872 campaign the tories obtained labour support and Macdonald and Campbell both provided revenue for the journal.

From all these activities it is clear how crucial a role Campbell played in the election of 1872. Macdonald left his own re-election in Kingston to Campbell, who evidently had charge as well of the other ridings in the old Midland District. Macdonald had found his power base here prior to confederation, but, active now on a larger stage, he delegated to Campbell much of the management of the party in the district. Of all the ridings he managed in 1872, the most important was Kingston, where he directed the prime minister’s re-election in detail. He kept Macdonald informed about what happened and he arranged his nomination. On 11 July he gloated over his manipulation of the Roman Catholic bishop of Kingston, Edward John Horan*: “The Bishop promised me today that he would speak to his people tomorrow – he is much pained at the disaffection particularly at this moment when half a dozen Catholics are running by your instrumentality – he says that he does not adopt the course of speaking in church but on the most important crises but he feels this to be one and will do it.” Nine days later, however, Campbell urged Macdonald to come to Kingston, for he felt that the seat was in danger from “some of the Catholics, some of your former friends and a lot of younger men.” He arranged for the return to Kingston of voters employed out of town and was able to keep Liberal voters on the job if they worked away from Kingston. Loyal supporters were looked after: some were paid, and unusually useful service could result in a patronage post. All the while Campbell was also active in constituencies from Toronto to the Ottawa River. He encouraged candidates and offered advice, found campaign funds, disciplined insufficiently friendly civil servants, persuaded men to continue to work for the party, appealed to religious leaders, and strove to minimize the disintegrating effects of factionalism. It is clear why Senator John Hamilton*, in a letter to Campbell in August, referred to elections “which you manipulate in Kingston.”

Campbell’s political career fits one standard 19th-century pattern. Through politics he rose to the highest level of Ontario’s social structure and joined the province’s élite. But his rise in politics was accomplished by his political utility, and did not depend on personal friendship with Macdonald. They were not close friends. The breakup of their law partnership in 1849 had been extremely unpleasant. Sir Joseph Pope*, Macdonald’s private secretary, would later comment, “Sir John and Sir Alexander were not kindred spirits, but any want of cordiality between them was on personal grounds, and politically they were always . . . closely united.” This political union was exceedingly useful to Macdonald; the very able Campbell performed a host of invaluable functions. In Senator Hamilton, the important Montreal business leader, Campbell had friend and confidant, and his own brother Charles linked him to Toronto’s business community. Sir Richard Cartwright and Oliver Mowat, men hated by Macdonald, remained lifelong friends of Campbell; at the very least they kept him informed in areas in which Macdonald had little contact. Despite his usefulness to Macdonald, however, Campbell represented no threat to his leader. He could not compete with Sir John at the personal level: Campbell was an aloof man, contemptuous of the masses and somewhat scornful of popular politics. He was more suited to the Senate than to the House of Commons, but he knew full well that a successful government must be based on politicians with strong electoral abilities and popularity throughout the country. Hence his comment to Macdonald in December 1872, “No appointment [to the cabinet] from the Senate can add anything to the strength of the Government with the Commons or the Country but the reverse.”

Campbell’s most serious political weakness was his lack of an independent power base: he operated from Kingston, the centre of Macdonald’s strength. During the last years of the union era he did have a base of electoral power, albeit a weak one, as an elected legislative councillor, but even then his constituency was shared with Macdonald. More important was his pre-1864 alliance with some elements of the tory old guard. Within the delicately balanced politics of the union, where governments and leaders were used up quickly, this strength was almost sufficient to obtain for him the leadership of the Upper Canadian Conservatives. After 1867 there was no elected federal upper house and it was impossible for small groups to wield the tremendous power they possessed before 1864. Campbell accepted the change, and, during Macdonald’s first federal government, he acted as a loyal and important lieutenant. His very inclusion in the first cabinet proves Macdonald’s esteem. Ontario had only five ministers in that cabinet, and the Ontario wing was a coalition, with three of the ministers (Adam Johnston Fergusson Blair, William Pearce Howland*, and William McDougall*) being Liberals, the two Conservatives being from Kingston, and only Macdonald having a seat in the Commons. That politically dangerous combination indicates how strongly Macdonald wanted Campbell’s assistance. Campbell was useful, safe, and able; he could not threaten Macdonald’s leadership, but he could further it. Sir Alexander Campbell was the ideal political lieutenant.

Alexander Campbell is the author of Speeches on divers occasions ([Ottawa?], 1885).

AO, MU 469–87; RG 24, ser.6. NA, MG 26, A. PAM, MG 12, B1, draft telegram, 19 Aug. 1873; telegram, Campbell to Morris, 21 Aug. 1873; B2. Can., Prov. of, Parl., Confederation debates; Royal commission to inquire into a certain resolution moved by the Honourable Mr. Huntington, in Parliament, on April 2nd, 1873, relating to the Canadian Pacific Railway, Report (Ottawa, 1873). Confederation: being a series of hitherto unpublished documents bearing on the British North America Act, ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1895). In memoriam: Sir Alexander Campbell, K.C.M.G., born March 9, 1822, died May 24, 1892 ([Toronto?, 1892?]). Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). CPC, 1864–87. Guide to Canadian ministries (1982). M. K. Christie, “Sir Alexander Campbell” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1950). Creighton, Macdonald, young politician. B. S. Osborne and Donald Swainson, Kingston: building on the past (Westport, Ont., 1988). Donald Swainson, “Personnel of politics”; “Alexander Campbell: general manager of the Conservative party (eastern Ontario section),” Historic Kingston, no.17 (1969): 78–92.

Cite This Article

Donald Swainson, “CAMPBELL, Sir ALEXANDER (d. 1892),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/campbell_alexander_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/campbell_alexander_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald Swainson |

| Title of Article: | CAMPBELL, Sir ALEXANDER (d. 1892) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |