Source: Link

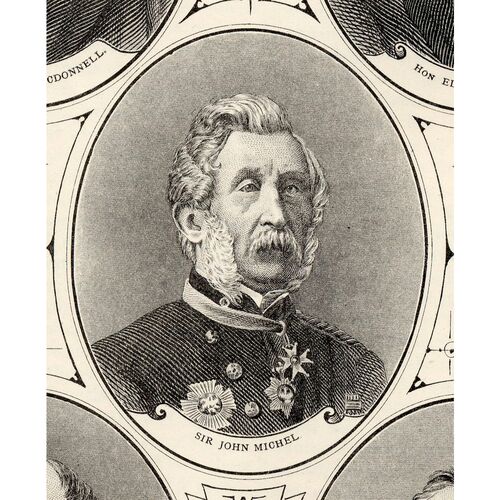

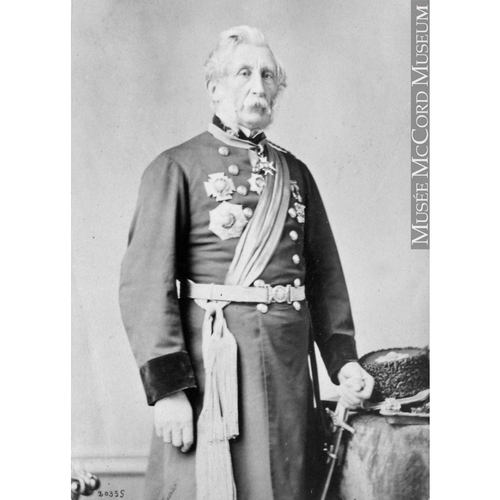

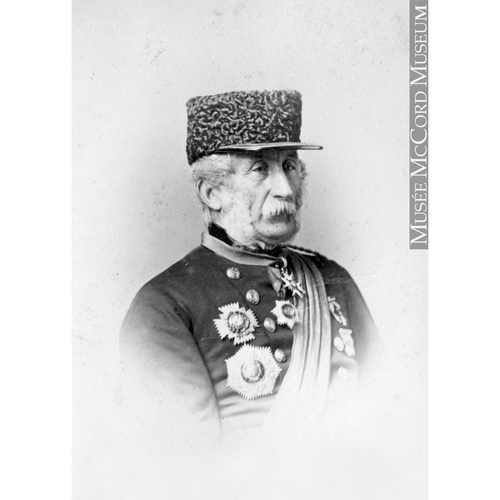

MICHEL, Sir JOHN, soldier; b. 1 Sept. 1804 in Dorset, England, son of Lieutenant-General John Michel and his second wife, Anne Fane; d. 23 May 1886 at the family seat, Dewlish House, Dorchester, Dorset.

John Michel was educated at Eton, and entered the army as an ensign in 1823. Most of his early service was in the 64th Foot. It is clear that his career was assisted by family connections and family wealth; but the fact that in 1832–33 he attended the senior department (later the staff college) of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, suggests a serious interest in his profession. From 1835 to 1840 he was aide-de-camp to his uncle, General Sir Henry Fane, who was commander-in-chief in India. On 15 May 1838 Michel married Louise Anne, a daughter of Colonel Chatham Horace Churchill, quartermaster general in India; they were to have at least two sons and three daughters. In 1840 Michel purchased a majority in the 6th Foot, and two years later the lieutenant-colonelcy of that regiment. The 6th was sent to South Africa in August 1846, and Michel commanded it there in the Kaffir Wars of 1846–47 and 1851–53, sometimes serving as commander of independent columns. During this, his first active service, he showed himself an energetic leader. James McKay, a sergeant in the 74th Foot, who saw him at work (he calls him Mitchell), says he was “the beau ideal of an able campaigning commander” and “a father and friend” to his men. After a period of home service in the brevet rank of colonel, he took part in the Crimean War as chief of staff of the Turkish contingent that was taken into British pay, as a local major-general.

After a short period of service in the Cape Colony, Michel was ordered to China in 1857; but en route his ship was wrecked and he was subsequently diverted to India, where the mutiny had broken out. In the last stages of the mutiny in 1858–59 Michel, now a substantive major-general, successfully conducted the pursuit of Tantia Topi, defeating his forces in a series of engagements and reducing him to the status of a fugitive who was shortly caught and hanged. At the end of 1859 Michel was sent to command a division in the war with China. His division took part in successful actions in August 1860, and in October it fell to it to burn the Summer Palace at Peking in reprisal for the torture and murder of British prisoners. Having become a kcb for his work in the mutiny, Michel was now promoted to gcb.

In June 1865 he succeeded Lieutenant-General Sir William Fenwick Williams in the command of the forces in British North America (the appointment was officially styled lieutenant-general on the staff). He remained in this command until October 1867, and thus had to deal with the first and most serious phase of the Fenian troubles. Whenever the Fenian menace moved the government of the Province of Canada to call out units of the volunteer force for active duty, these were placed under Michel by order in council and he exercised command over regulars and volunteers alike. Nine companies of volunteers were so called out for frontier service in November 1865; at the same time Michel reinforced the regular garrison of London, Canada West, and took steps to improve the telegraph network in the eastern part of the upper province. In March 1866, 10,000 volunteers were called out (the actual number appearing for duty turned out to be 14,000), and in the crisis caused by the raids of June 1866 [see Alfred Booker*] the whole volunteer force of Canada, some 20,000 men, was called out and placed under Michel. He had asked for, and obtained, two more regular battalions from the United Kingdom in March 1866 and in August a panic caused in Canada West by renewed Fenian threats led Michel, in conjunction with Viscount Monck*, the governor general, to ask the British government for still larger reinforcements. These were sent, in numbers only slightly smaller than had been requested; and in the spring of 1867 there were over 15,000 regulars under Michel’s command. Monck soon began to incline to the view that the force might be somewhat reduced but Michel opposed any reduction.

For two long periods, 30 Sept. 1865–12 Feb. 1866 and 10 Dec. 1866–25 June 1867, Michel was administrator of the government in Monck’s absence, though he did not move from his headquarters at Montreal. Writing to John A. Macdonald* in February 1866 to say that he expected raids and would like to see more volunteer companies called out, he said whimsically, “In writing this note, I am consulting with my Minister of War, giving him the opinions of the Commander of the Forces, which, as Administrator I think it would be desirable to carry out.” Generally speaking, Michel sought to prevail on the colonials to take on a larger share of the defence burden, while Canadian ministers, unwilling to incur expense, preferred to leave it with the regulars. Early in 1867 Alexander Campbell*, the acting minister of militia, wrote to Macdonald in England describing how Michel, on the basis of intelligence received, sent “of his own motion of course” Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley* to negotiate with General George Gordon Meade of the United States Army, and also asked Campbell to call out “the Volunteers.” Campbell politely demurred. In consequence, he wrote, “Our Volunteers are still sleeping with their wives to the great comfort of both and with great prospective benefit to the country.”

Michel was painfully aware of how inadequate and exposed were the country’s military communications. In August and September 1865, soon after his arrival in Canada, he made a reconnaissance by canoe, in company with Admiral Sir James Hope, commanding the Royal Navy’s American station, of the route between the St Lawrence and Lake Huron by the French River, Lake Nipissing, and the Mattawa and Ottawa rivers. He cautiously advised against either setting up a crown colony at Red River or uniting the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territories with Canada until “a safe communication for military purposes” was established with Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg). In October 1865 he gave the engineer Casimir Stanislaus Gzowski* a letter to the colonial secretary explaining that he considered the Ottawa–French River navigation route, which Gzowski was promoting, vital to the country’s security. In a valedictory message to the Canadian people he urged the importance of this project. During his last months in Canada he expressed the opinion that the Fenian movement was now “torpid,” and also recorded an optimistic view of the prospects for Anglo-American peace. Michel’s Canadian command was cut short by concern for his wife’s health. When he left Montreal for England on 15 Oct. 1867, having been succeeded by Sir Charles Ash Windham*, he received addresses from the city corporation and the Montreal volunteers warmly praising his work as commander and administrator.

In 1873 Michel was placed in charge of the first “autumn manoeuvres” held in England, a development which can be traced to the influence of the Franco-Prussian War. From 1875 to 1880 he was commander-in-chief in Ireland, where his “social qualities and ample means” are said to have made him popular and where he became an Irish privy councillor (and thus Right Honourable). In March 1885, a little more than a year before his death, he was made a field-marshal.

Field-Marshal Sir Henry Evelyn Wood, who served under Michel in India as a subaltern, described him as “a clever, handsome, well-educated officer, a fine horseman, active and of great determination.” He served in Canada at a difficult and critical period, and his work seems to have been competently done. Campbell’s letter to Macdonald in 1867 suggests that the Canadian ministers tended to think him something of a fussbudget, but Macdonald wrote in 1866: “There is not a more active or zealous officer than Sir John Michel.”

PAC, MG 26, A, 57–59, 100; RG 7, G1, 163–65; G6, 16–17; G9, 44–47; G10, 1–2. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1867–68, VII, no.35. Can., Prov. of, Parl., Sessional papers, 1866, II, no.4. [J. A. Macdonald], Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . , ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1921). James McKay, Reminiscences of the last Kafir war, illustrated with numerous anecdotes (Grahamstown, South Africa, 1871; repr. Cape Town, 1970). G. J. Wolseley, Narrative of the war with China in 1860 . . . (London, 1862; repr. Wilmington, Del., 1972); The South African diaries of Sir Garnet Wolseley, 1875, ed. Adrian Preston (Cape Town, 1971). Montreal Gazette, 16 Oct. 1867. Times (London), 25 May 1886. The annual register: a review of public events at home and abroad (London), 1886. DNB. G. B., WO, Army list, 1824. Hart’s army list, 1852; 1856; 1866; 1872. Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, II. Creighton, Macdonald, young politician. J. W. Fortescue, A history of the British army (13v. in 14 and 6v. maps, London, 1899–1930), XII–XIII. J. M. Hitsman, Safeguarding Canada, 1763–1871 ([Toronto]), 1968). A. J. Smithers, The Kaffir wars, 1779–1877 (London, 1973). C. P. Stacey, Canada and the British army, 1846–1871: a study in the practice of responsible government (London and Toronto, 1936; rev. ed., [Toronto], 1963). Evelyn Wood, The revolt in Hindustan, 1857–59 (London, 1908).

Cite This Article

C. P. Stacey, “MICHEL, Sir JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/michel_john_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/michel_john_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. P. Stacey |

| Title of Article: | MICHEL, Sir JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |