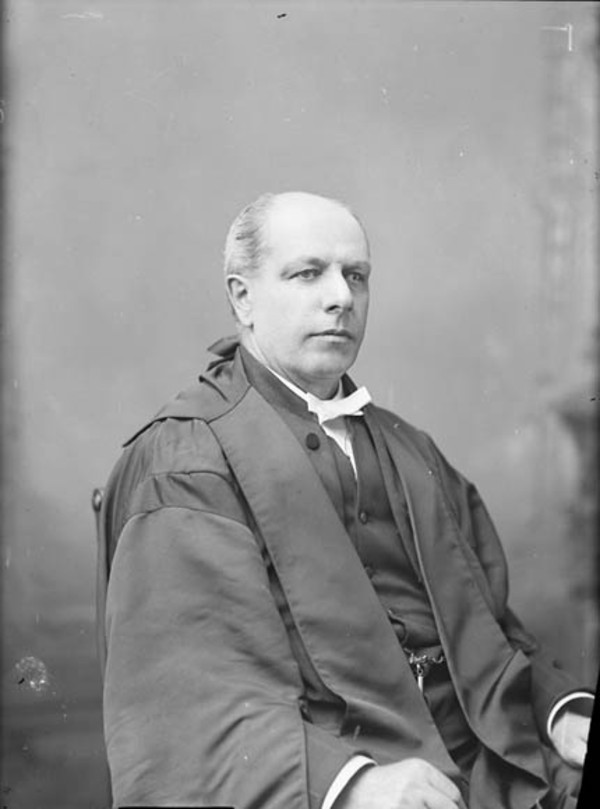

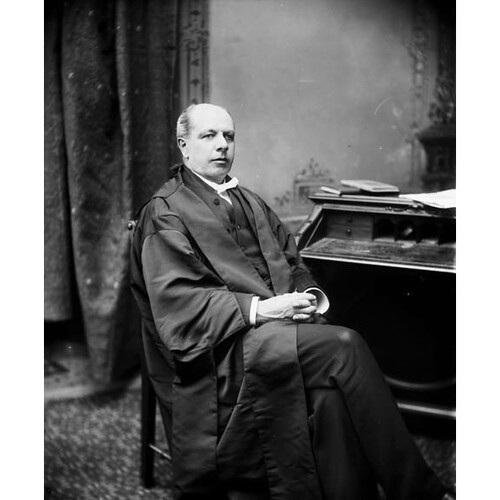

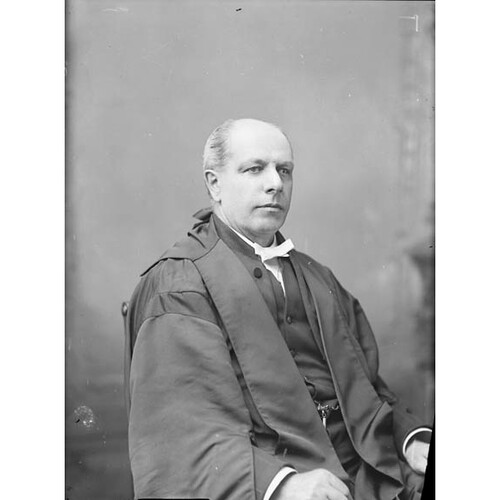

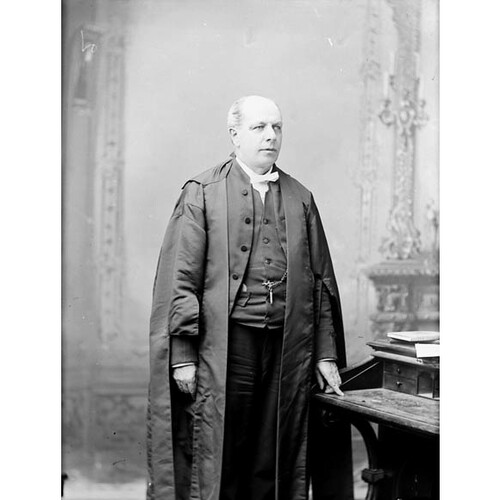

BOURINOT, Sir JOHN GEORGE, journalist, historian, littérateur, civil servant, and expert in parliamentary procedure and constitutional law; b. 24 Oct. 1836 in Sydney, N.S., son of John Bourinot* and Margaret Jane Marshall; m. first 1 Sept. 1858, in Toronto, Bridges Delia Houck (d. 1861), a widow, and they had two sons; m. secondly 3 Oct. 1865 Emily Alden Pilsbury (d. 1887) in Halifax, and they had one son and two daughters; m. thirdly 3 July 1889 Isabelle Cameron in Regina, and they had two sons, one of whom was Arthur Stanley; d. 13 Oct. 1902 in Ottawa.

John George Bourinot’s father was one of Sydney’s most prominent citizens, representing Cape Breton County in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1859 to 1867 and serving in the Senate from 1867 until his death in 1884, and his mother was the daughter of John George Marshall*, a justice of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas for Cape Breton. Bourinot received his early education under the Reverend William Young Porter, who was amazed by his pupil’s “quickness of perception, and the intellectual grasp which he exhibited.” Encouraged by this assessment, in 1854 John Bourinot sent his son to Trinity College, Toronto. John George proved an excellent student, but, probably for financial reasons, he left in 1856 without obtaining a degree. He would nevertheless be associated with Trinity for the rest of his life, becoming a member of its council and sometimes lecturing and examining in constitutional law and political science.

For a short time after leaving Trinity, Bourinot was the parliamentary reporter of the Toronto Leader [see James Beaty*]. By October 1858, however, he had returned to Sydney, where on the 13th he signed articles of clerkship with attorney James Charles McKeagney*. The term was to be five years, but Bourinot did not complete it; he is said to have dreaded a life of professional routine in the law. He may have spent a short time in the United States before moving to Halifax, where in 1860 he and Joseph C. Crosskill launched the Reporter, an evening tri-weekly journal later called the Evening Reporter. They would jointly own and edit it for seven years. Soon after founding the Reporter, Bourinot entered into an agreement with Provincial Secretary Joseph Howe* to report the debates of the House of Assembly. He continued this work until May 1867, when he relinquished the newspaper to Crosskill. It is not clear why Bourinot left the Evening Reporter. He may have wanted to try his hand at freelance writing, or he may have had reason to expect an appointment soon after confederation to the staff of the Senate (an appointment that in fact did not come for two years). The Evening Reporter had supported confederation; three of Bourinot’s articles on the subject published there had been reprinted as Confederation of the provinces of British North America (Halifax, 1866).

Perhaps his most important writing immediately after confederation was a series of letters in 1868 to the Ottawa Times entitled “The state of affairs in Nova Scotia.” Written between 23 January and 28 November, the letters trace the development of the movement in Nova Scotia for the repeal of the British North America Act, showing the split between Howe, who by the latter date had given up the fight for repeal and was negotiating with Ottawa for “better terms,” and members of the assembly, such as Attorney General Martin Isaac Wilkins*, who in the absence of repeal seemed ready to establish a Nova Scotian republic. Although a strong unionist, Bourinot claimed that Nova Scotia had valid grievances and urged Ontario and Quebec to conciliate the people of the Maritime provinces. The letters were sometimes accompanied by editorial comment; on 7 March Bourinot was described as “our well-informed and observant correspondent.” During this period his interest in the history and geography of his native province was revealed in articles such as “Notes of a ramble through Cape Breton,” published in the New Dominion Monthly (Montreal) in May 1868.

Before writing the Times letters Bourinot had returned to Sydney, where he remained until moving to Hull, Que., following his appointment to “the vacant English Clerkship” in the Senate in May 1869. In May 1870 a recommendation that he be styled “Short Hand Writer” to the Senate and its committees was adopted. At the same time the Senate decided to publish its debates, beginning with the 1871 session, and Bourinot took on the task of reporting them.

In spite of these added responsibilities, Bourinot continued his freelance writing. He tried his hand at fiction, “Marguerite: – a tale of forest life in the new dominion” being published in the New Dominion Monthly from January to June 1870. The title is misleading, not only because Marguerite plays a minor role but also because the story does not take place after confederation but rather opens in 1756, “when the great contest between France and England for the supremacy in America was about to begin.” A rather disjointed tale, which Bourinot described as “‘founded on facts,’” it involves the capture of Osborne, an officer of the British garrison in Halifax, by Micmac, his rescue by a French officer, in which a handsome Indian girl, Winona, plays an important part, and his marriage to Marguerite, recently restored to her family from Indian captivity. As an adventure the story is quite exciting, but the romantic element is weak; one learns almost nothing about Marguerite, and the role of heroine might better have been assigned to Winona. Indeed, Bourinot admits in the fifth instalment that many of his readers, “especially among the female portion,” will have been disappointed at the absence of “‘love passages.’” “Marguerite” was Bourinot’s only published novel, but he did write a few short stories between 1869 and 1877.

A decade after the appearance of “Marguerite,” Bourinot commented about Canada that “though there have been many attempts at fiction, the performance has, on the whole, been weak in the extreme.” His opinion had not changed by 1893, when he stated that “there is one respect in which Canadians have never won any marked success, and that is in the novel or romance.” Accurate, well-written history, he maintained, had a “much deeper and more useful purpose” in culture and education than fiction, but the novel or romance would be written as long as most people sought “amusement rather than knowledge.” It is well that in later life Bourinot concentrated on writing in areas other than fiction, for he would probably never have attained great success in that field.

Bourinot had been appointed second clerk assistant of the House of Commons in April 1873, and it was probably at this time that he moved from Hull to Ottawa. Named first clerk assistant in February 1879, he became clerk of the commons on 1 Dec. 1880, and served with distinction in this position until his death. As senior administrative officer and recording officer of the commons, Bourinot took minutes of its proceedings and certified bills and orders. An important part of his duties was to advise the speaker on matters of procedure. In time Bourinot became an institution in the commons, and a newspaper article of 1894 described him as “seemingly the busiest person in the House,” one who maintained a “grave and dignified silence” at all times.

It was after becoming clerk that Bourinot did his best and most important writing. He continued to deal with the history of his native province and to comment on current events affecting Canada, but he also wrote, in more substantial works, on a variety of broader topics, including Canadian history and government. His contributions became well known internationally, some appearing in prominent British journals such as Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine and the London Quarterly and Holborn Review.

One of Bourinot’s favourite subjects was comparative government; he especially enjoyed comparing the Canadian and American systems. He was also interested in the Swiss federal system because in some ways it resembled the Canadian and in others the American. Though he clearly preferred the Canadian system to the American and frequently spoke out against American annexationist sentiments, his work was well received in the United States, and many of his historical papers were published in the Magazine of American History (New York). He also lectured there, and he was a member of the councils of the American Historical Association and the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

An article in the Canadian Parliamentary Review in 1984 noted that Bourinot has “some claim to being considered the first political scientist in Canada.” Certainly he promoted the teaching of political science in Canadian universities, asserting in 1889 that “no institution of learning should keep exclusively within the old beaten paths of classical and mathematical learning.” His ideal course in Canadian political science combined the study of contemporary government with that of the political and constitutional history of Canada, Britain, and France.

A recurring theme in Bourinot’s historical writing is that there were three well-defined eras of development in Canada, the French regime, the period from the conquest to confederation, and the period from confederation to the time of writing. Bourinot considered that the French regime, though it contained heroic and picturesque features and was the source of much later literature, was not characterized by intellectual development because “the absolutism of old France crushed every semblance of independent thought and action.” He believed that in the second period the emphasis was on the struggle for responsible government. Intellectual development began, but there was little original literature worthy of special mention. After the attainment of responsible government, and especially after confederation, Canada entered an era of intellectual, as well as material, activity, in his study of which Bourinot gave proper weight to the contributions of Canadians of French origin. “The French Canadian is animated by a deep veneration for the past history of his native country, and by a very decided determination to preserve his language and institutions intact; and consequently there exists in the Province of Quebec a national French Canadian sentiment, which has produced no mean intellectual fruits.”

In Our intellectual strength and weakness; a short historical and critical review of literature, art and education in Canada (Montreal, 1893), Bourinot notes creditable achievements in history, poetry, and essays. The poems of Octave Crémazie*, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, Joseph Howe, Charles Sangster*, and others were for him “imbued with a truly Canadian spirit,” and he thought that since the days of François-Xavier Garneau* and Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland* historical literature had continued “to enlist the earnest and industrious study of Canadians.” For Bourinot, fiction, poetry, and criticism alone did not constitute literature, which embraced pamphlets and monographs on scientific, mathematical, geographical, and other subjects. “It is not so much the subject as the form and style which make them worthy of a place in literature.”

Two of Bourinot’s later books, How Canada is governed (Toronto, 1895) and Canada under British rule, 1760–1900 (Cambridge, Eng., 1900), were popular during his lifetime and for some time after. How Canada is governed was in its fifth edition at the time of his death, and it was used as a textbook in several provinces. Canada under British rule is a readable and well-balanced account; it includes an introductory chapter on the French regime. Bourinot’s last book, Lord Elgin (Toronto, 1903), appeared posthumously. It deals mainly with Elgin [Bruce*] as governor general and is not a full biography.

By far Bourinot’s best-known works, and those on which his reputation now chiefly rests, are Parliamentary procedure and practice . . . in the dominion of Canada (Montreal, 1884) and A Canadian manual on the procedure at meetings . . . (Toronto, 1894). Parliamentary procedure particularly notes differences which had developed between British and Canadian practices and includes “an introductory chapter upon the origin and gradual development of parliamentary institutions” in Canada. This chapter Bourinot revised as A manual of the constitutional history of Canada . . . (Montreal, 1888).

Parliamentary procedure was compared favourably with the classic British book on the subject by Sir Thomas Erskine May, clerk of the British House of Commons. Timothy Warren Anglin*, a former speaker of the Canadian House of Commons, considered the organization of Parliamentary procedure “more scientific than that of May’s work,” and an Australian reviewer stated that “in clearness of treatment, in method of arrangement, in fullness of precedent . . . we shall expect the student to award the palm to the Canadian author.” Sir Reginald Francis Douce Palgrave, May’s successor, also had a high opinion of Bourinot’s work. A second edition appeared in 1892. Bourinot had done much of the revising for a third edition before his last illness; the task was completed by Thomas Barnard Flint, his successor as clerk of the commons.

After the publication of Parliamentary procedure, Bourinot was “in constant receipt of enquiries on various points of order” which had arisen in “municipal and other meetings.” The experience led him to recognize the need for a treatise to address “the special wants of municipal councils, . . . shareholders’ and directors’ meetings, and societies in general,” and A Canadian manual was the result. It soon became apparent that the book was too long and expensive for some of the groups which wanted to use it, and Bourinot therefore prepared a shorter version. The latter’s title page described it as an abridgement of “the author’s larger work,” and it is often incorrectly assumed today that the “larger work” was Parliamentary procedure. The original version of A Canadian manual is now practically unknown, but the abridgement has been reprinted several times and revised and updated by others.

Despite his popularity, Bourinot attracted his share of criticism. In 1882 Nicholas Flood Davin called him a “literary fraud” and a “murderer of the Queen’s English.” Bourinot thought the reason for the attack was that “Davin believed (wrongly) that I had kept him out of the Royal Society”; in fact, no one had proposed him for membership. The two were evidently later reconciled. Henry James Morgan* praised Bourinot’s writing in Bibliotheca canadensis (1867), but for unknown reasons he became critical and in 1898 appears to have intentionally excluded Bourinot from his Canadian men and women of the time. As well, some American newspapers took exception to Bourinot’s stand against annexation and his preference for the British/Canadian system of government.

When the Royal Society of Canada was founded in 1882 Bourinot had become honorary secretary, and he retained the position until his death. He was elected vice-president in 1891 and president in 1892, serving the customary one-year terms. He also supervised the publication of 19 volumes of the society’s Proceedings and Transactions, to which he contributed many important papers. The author of one biographical sketch wrote, “To his efforts the Society largely owed its success. . . . No one can sufficiently appreciate the attention he gave to the Society’s business, and the interest he took in its work.” Others were equally complimentary.

An ardent advocate of imperial federation, Bourinot was for many years honorary corresponding secretary of the Royal Colonial Institute of London, England. The opinions of the supporters of imperial federation tend to be downgraded by modern Canadian historians, but at the time their views were popular and considered reasonable, and they were sincerely held. Similarly, although Bourinot’s admiration for “the Teutonic people, the noblest offspring of the Aryan family of nations,” from whom he traced the development in England of free institutions and parliamentary government, would today be regarded as racist, it should be seen in context. The same can be said of his treatment of the North American native peoples in his fictional and historical writing.

In some ways Bourinot was ahead of his time. As early as 1881 he had recognized the need for a national library, something which would not be approved until 1952. At a period when the right of women to higher education was just beginning to be acknowledged, he spoke in its favour, describing it as “an illustration in itself of the intellectual development that is now going on among us.” He was also an advocate of the establishment of a national university.

Because Bourinot was an authority not only on parliamentary procedure but also on constitutional law and history, he was consulted by those prominent in public life on matters that would not normally be referred to the clerk of the commons, especially in the years of uncertainty following the death of Sir John A. Macdonald* in 1891. During Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*]’s term as governor general, Bourinot frequently gave advice both to him and to Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*], on constitutional matters as well as on procedure at the meetings of organizations with which Lady Aberdeen was associated, such as the National Council of Women of Canada and the Victorian Order of Nurses. His friendship with the Aberdeens continued until his death.

In private life, Bourinot was “one of the kindliest and most genial of men,” devoted to his children and fond of playing with them. He enjoyed entertaining, and the latest volumes of romance, history, and poetry were discussed at literary evenings at his home, which were attended by guests such as Horatio Gilbert Parker*, Martin Joseph Griffin, Archibald Lampman*, and Emily Pauline Johnson*. In conversation he was said to be “even more entertaining than on the platform or in his books” because there he was able to display his “quiet vein of humor.”

Bourinot received many honours during his lifetime. He was awarded a cmg in 1890, a kcmg in 1898, and honorary degrees from almost all Canadian universities. These honours were a recognition of his achievements in many areas but especially of his work on parliamentary procedure.

[There has, unfortunately, been no modification of Bourinot’s parliamentary procedure since a fourth edition, prepared by Thomas Barnard Flint, appeared at Toronto in 1916. The first edition has been reprinted (Shannon, Republic of Ire., 1971); Charles Beverley Koester’s introduction includes a summary of Bourinot’s life, pp.5–12 (paged separately from the reprinted text). A research project which aims to publish a comprehensive manual on parliamentary procedure is under way in Ottawa. Most appropriately, it has been named after Bourinot.

The second and third revisions of A Canadian manual, ed. J. G. Dubroy (Toronto, 1963) and G. H. Stanford (Toronto, 1977), have been known as Bourinot’s rules of order, a title which was used on the cover as early as 1918 and was probably adopted in order to make the manual competitive with Robert’s rules of order . . . (Chicago, 1876, and subsequent editions), the leading American work, which is widely used in Canada. The change of name is unfortunate because the books serve different purposes. Robert’s is a complete rule book, suitable for organizations which do not wish to write rules of order; Bourinot’s deals mainly with general principles and is more useful for organizations which have adopted their own rules of order and rely on it only in unprovided cases.

No definitive bibliography of Bourinot’s writings exists. A list of his works to 1894 is in his “Bibliography of the members of the Royal Society of Canada,” RSC Trans., 1st ser., 12 (1894), proc.: 1–79, which was also issued as a pamphlet ([Ottawa], 1894). Bourinot’s publications are listed in chronological order on pp.16–18, beginning with 1866. The bibliography is especially useful because it groups items published in several places under the date of first publication and indicates whether reprints are “in full” or “in abstract.” It is not, however, complete or accurate: corrected and fuller entries for the short stories, for instance, appear in Carole Gerson, A purer taste: the writing and reading of fiction in English in nineteenth-century Canada (Toronto, 1989), 180, n.25. A reprint of Our intellectual strength and weakness, introduced by Clara [McCandless] Thomas, was published at Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., in 1973.

Bourinot’s major publications after 1894 are: How Canada is governed . . . (Toronto, 1895). This work went through twelve editions, the fifth in 1902, shortly before the author’s death. Later editions were updated by others, the last one (1928) by his son Arthur Stanley. An American version of the first edition was also issued (Boston, 1895). Canada (New York and London, 1896, and subsequent eds.). The 1896 New York edition was issued under the title The story of Canada. Builders of Nova Scotia . . . ([Ottawa], 1899); (Toronto, 1900). Canada under British rule, 1760–1900 (Cambridge, Eng., 1900); (Toronto, 1901). A revised edition, . . . 1760–1905, with an addition by George MacKinnon Wrong*, was published at Cambridge in 1909. Lord Elgin, issued posthumously (Toronto, 1903, and subsequent reprintings).

The Bourinot papers in NA, MG 27, I, I62, consist mainly of letters written to him between 1881 and 1902. His scrapbooks, containing newspaper clippings and letters, are in PANS, MG 1, 145–49 (the series includes more than five volumes: two volumes are numbered 145 and there are also vols.145A, 146A, and 147A; vol.145A, however, does not relate to Bourinot). The PANS Library holds a volume entitled “Opinions on questions of parliamentary and constitutional procedure,” which consists mainly of his manuscript and typescript opinions on a variety of topics. Also in the library is Bourinot’s copy of the first edition of Parliamentary procedure, with many handwritten notes, which were presumably made while he was preparing the second edition. The papers of Arthur Stanley Bourinot in National Library of Canada (Ottawa), C1, also contain material relating to his father. m.a.b.]

ACC, Diocese of Toronto Arch., Toronto, Trinity East (Little Trinity Church), reg. of marriages, 1 Sept. 1858. Beaton Institute, University College of Cape Breton (Sydney, N.S.), MG 12, 16 (Bourinot papers). [These consist mostly of copies of material from other institutions; they have been used primarily for copies of Bourinot’s letters to Sir John A. Macdonald from the latter’s papers in NA, MG 26, A.] NA, RG 31, C1, 1881, Ottawa, Wellington Ward, dist.105. PANS, Churches, St Luke’s Anglican (Halifax), reg. of baptisms, 17 April 1862 (mfm.); RG 39, CB, M, 1, no.55. St George’s (Anglican) Church (Sydney), Reg. of baptisms, 10 Dec. 1836. H. F. G[adsby], “A hard man to follow,” Toronto Daily Star, 3 March 1902. Halifax Reporter, 1860–64, and its successor, the Halifax Evening Reporter, 1864–67. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 4 Oct. 1865.

Appletons’ cyclopædia of American biography, ed. J. G. Wilson et al. (10v., New York, 1887–1924), 1: 330. M. A. Banks, “New insights on Bourinot’s parliamentary publications,” Canadian Parliamentary Rev. ([Ottawa]), 15 (1992–93), no.1: 19–25. Paul Benoit, “The politics and ethics of John George Bourinot,” Canadian Parliamentary Rev., 7 (1984–85), no.3: 6–10. [Reproduces a photograph of Bourinot in NA, Documentary Art and Photography Div., PA–25659 (negative copy).] Carl Berger, “Race and liberty: the historical ideas of Sir John George Bourinot,” CHA Report, 1965: 87–104. Morgan, Bibliotheca canadensis. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. George Stewart, “John George Bourinot,” Men of the day: a Canadian portrait gallery, ed. L.-H. Taché (32 ser. in 16v., Montreal, 1890–[94]), 26th ser.

Cite This Article

Margaret A. Banks, “BOURINOT, Sir JOHN GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourinot_john_george_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourinot_john_george_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Margaret A. Banks |

| Title of Article: | BOURINOT, Sir JOHN GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |