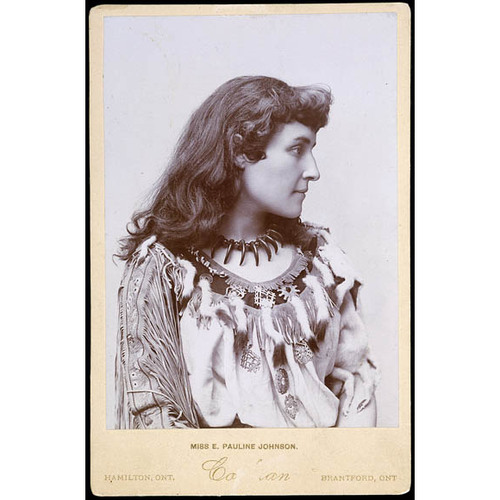

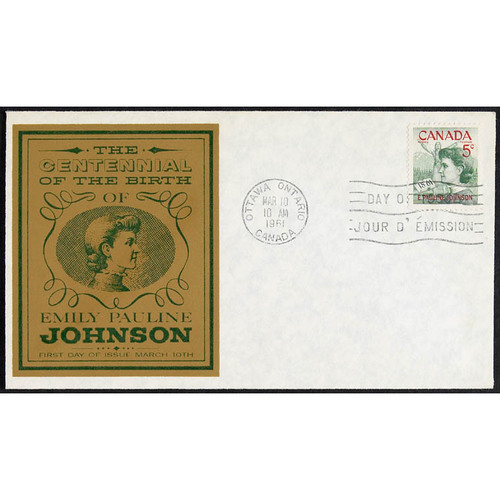

JOHNSON, EMILY PAULINE, author and performer; b. 10 March 1861 on the Six Nations Reserve, Upper Canada, daughter of George Henry Martin Johnson* and Emily Susanna Howells; d. unmarried 7 March 1913 in Vancouver.

Pauline Johnson, the youngest of four children, was born at Chiefswood, an imposing residence built by her father. The house, with its identical entrances, one facing the road and the other the Grand River, seems emblematic of her status as a mixed-blood writer and performer who straddled two cultures. Although her mother was English, Johnson was native by birth, her father being a Mohawk of the wolf clan. The great-granddaughter of Tekahionwake (Jacob Johnson), whose name she would later adopt, and the granddaughter of John “Smoke” Johnson*, known for his skill as an orator, she saw herself as primarily “Indian.” At the same time, she embraced Canada, particularly the emerging west, as her larger home and reflected that response in her work.

Johnson was raised in privileged, middle-class circumstances on the outskirts of Brantford, a bustling manufacturing town. Her father was acculturated to European values. He spoke English, French, and German, as well as the languages of the Six Nations Confederacy, wore conventional Canadian dress except for ceremonial occasions, and worked for the federal government in various capacities. Her mother emphasized refinement and decorum in raising her children, cultivating in them an aloof dignity that she felt would earn them respect in the larger world. Their home, because of George Johnson’s stature and reputation, attracted such distinguished guests as the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell] and Princess Louise*, Prince Arthur*, Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*] and his wife, Garnet Joseph Wolseley, and artist Homer Ransford Watson*. Pauline’s often-noted elegant manners and aristocratic air owed much to this background and training.

Her formal education was modest. Tutored largely at home, she attended the reserve school for two years and then Brantford Collegiate Institute from the age of 14 to 16. Well read in English literature, particularly Browning, Scott, Byron, and Tennyson, and having performed in amateur theatricals at school, she returned to her parents’ home in 1877 and settled into a life typical of leisured young women of her time awaiting marriage. She visited and received friends, and spent long hours canoeing on the Grand River, a fashionable pursuit for women of her era, but one at which Johnson excelled and to which she would turn for pleasure and solace throughout her life.

This idyllic existence ended abruptly when George Johnson died in 1884. Unable to afford living at Chiefswood, Pauline, her mother, and her sister, Eliza Helen Charlotte (Eva), moved to rented quarters in Brantford. At 23, without marriage prospects, she began to look to writing as a means of supporting herself. Between 1884 and 1886 she succeeded in publishing four poems in Gems of Poetry (New York) and eight in the Week (Toronto). As well, she produced several occasional pieces, such as a poem written for the ceremony marking the reinterment of Seneca orator Red Jacket [Shakóye:wa:tha?*] at Buffalo, N.Y., in 1885 and another for the dedication of a statue of Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*] in Brantford the following year. As her reputation grew, she began in 1886 to sign her work as both E. Pauline Johnson and Tekahionwake, accentuating her native identity and developing the “Indian princess” persona that would serve her well. At the same time, however, her double signature suggests the complexity of Johnson’s location as a writer and performer of mixed blood who spoke from both inside and outside native experience. On the one hand, she continually emphasized the nobility of certain values that she associated with native communities, particularly respect for nature and generosity of spirit. On the other, she frequently lamented the stereotyping of native figures (as, for example, in her essay “A strong race opinion on the Indian girl in modern fiction”), despite the fact that a number of her own poems, such as “Dawendine,” appear to contribute to that mythology.

By the end of the decade she had been interviewed by “Garth Grafton” (Sara Jeannette Duncan*, who had attended school in Brantford with Johnson) for the Toronto Globe. She had established a friendship by correspondence with poet Charles George Douglas Roberts*. Two of her poems had been published in William Douw Lighthall*’s anthology Songs of the great dominion . . . (London, 1889). Her work had been singled out for praise by Walter Theodore Watts-Dunton in the London Athenæum in 1889, and she had received a letter of encouragement from the elderly American poet John Greenleaf Whittier, who applauded the strength and beauty of her verse.

None the less, an income from writing eluded Johnson until January 1892, when school friend Frank Yeigh*, now president of the Young Men’s Liberal Club in Toronto, invited her to participate in an evening of poetry sponsored by the group. Her success with this first audience, who thrilled to her dramatic recitation of her poems, particularly “A cry from an Indian wife” and “As red men die,” led to some 125 performances in 50 Ontario towns and villages between October that year and May 1893. Her beauty and grace as a performer, her dignity and aristocratic bearing, her highly emotional delivery at a time when sentimentality and melodrama were popular on the stage, and her emphasis on her links to oral tradition through her native blood combined to ensure her immediate success as a recitalist. In late 1892 Johnson began to appear in her trademark costume: native dress for the first half of her program and a drawing-room gown for the second. Her repertoire now included her signature poems “The song my paddle sings” and “Ojistoh.” Pauline Johnson had emerged, not as the serious poet she longed all her life to be, but as a popular performer of her own material.

For the next 17 years, she toured Canada from coast to coast, as well as parts of the United States. Partnered by Owen Alexander Smily (1892–97) and J. Walter McRaye (1901–9), she performed with remarkable good humour and tenacity in venues ranging from the elegant to the rudimentary, not only in major cities but also in remote settlements accessible only by stagecoach or buckboard. In 1894 she presented a series of successful recitals in London, England, and while there arranged for the publication of her first book of poems, The white wampum (London, Toronto, and Boston, [1895]). Her second collection, Canadian born (Toronto), appeared in 1903. Reflecting Canadian experience more generally and embodying the patriotic sentiments typical of the era of the South African War, it proved less successful than the earlier volume, with its emphasis on native subjects and experience, had been. In fact, Johnson’s poetry is more wide-ranging and exploratory than the traditional focus on her lyrics of landscape and native life might suggest. Some of her poems celebrate the country’s recreational north (as in “Under canvas” and “The camper”), others reflect the intense nationalism and idealism of Edwardian Canada (such as “Canadian born” or “Prairie greyhounds”) or explore Christian themes (“Brier” and “Christmastide”), and still others are light or comic in tone (for example, “Canada (acrostic)” and “A toast”). Together these themes suggest a broader and more engaged sensibility than that usually attributed to her.

In 1906 Johnson returned to London, and while there met Squamish chief Joseph Capilano [Su–á-pu-luck*] and his delegation to Edward VII, in England to protest hunting and fishing restrictions recently imposed upon natives of the British Columbia coast by the Canadian government. Her friendship with “Chief Joe” would reinforce her own growing attraction to the west coast and culminate in her retelling of his stories in Legends of Vancouver (Vancouver, 1911). After returning to Canada, she resumed her touring schedule with McRaye and in 1907 included an American Chautauqua circuit for the first time. According to her biographer Betty Keller, she made in all at least seven western Canadian tours, nine to the Maritimes, four to the American Midwest, and five to the eastern seaboard of the United States, as well as the two London seasons. Throughout these years of arduous touring, Johnson published prose pieces in a variety of Canadian and American periodicals, notably Mother’s Magazine and Boys’ World (both of Elgin, Ill.), for which she wrote the uplifting stories and essays popular at the time. In 1909, weary and already ill with the breast cancer that would take her life, she ended her partnership with McRaye and retired to Vancouver. However, she still performed or lectured on Mohawk traditions from time to time as her health permitted.

It would be difficult to overstate the personal difficulties that Pauline Johnson endured in bringing her work before the public. The death of her mother in 1898 and the subsequent rupture of ties with her sister and with Brantford and her birthplace, the termination of her engagement to Winnipeg insurance inspector Charles Robert Lumley Drayton at his request in 1900, misfortunes at the hands of an unscrupulous manager that year, and serious bouts of streptococcal illness between 1900 and 1902 (which caused the loss of her hair and left her skin ravaged) all took their toll. Nor was she financially secure: throughout her life she earned little from her publications, while income from touring tended to evaporate quickly, given her expenses and her well-known generosity and lack of financial acumen.

The circumstances surrounding her death attest to the great esteem in which Johnson was held. Friends such as Vancouver editor Lionel Waterloo Makovski and Isabel McLean (the columnist Alexandra of the Vancouver Daily Province) assisted her in the completion of Legends of Vancouver and Flint and feather (Toronto, [1912]), a collected edition of her poems which she managed to proofread with assistance just a few months before her death. A local committee, established by McLean and including representatives of the Canadian Women’s Press Club and the local Women’s Canadian Club, raised money for Johnson’s care and began to prepare for publication two collections of her prose works.

Following Pauline Johnson’s death on 7 March 1913, her friends arranged a funeral from Christ Church Cathedral and burial in Stanley Park within sight of Siwash Rock, as she had requested. A memorial service was also held in the Mohawk chapel at the Six Nations Reserve. A monument, erected by the Women’s Canadian Club in 1922, marks her burial site in Vancouver, and a granite boulder with an inscription reading “E. Pauline Johnson, Mohawk Indian . . .” in the Johnson family plot at the Mohawk chapel records her place of origin and her genesis.

A number of Pauline Johnson’s prose pieces, originally published in Mother’s Magazine and Boys’ World, were collected and issued after her death in The moccasin maker, with introduction by [Horatio] Gilbert Parker* and appreciation by Charles Mair* (Toronto, 1913), and in The Shagganappi, with introduction by Ernest Thompson Seton* (Toronto, 1913). The 1913 text of The moccasin maker was reprinted with a new introduction and with annotation and bibliography by A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff (Tucson, Ariz., 1987). Flint and feather was later revised and enlarged, and both it and Legends of Vancouver have been reprinted many times. Several of Johnson’s poems have been put to music.

Johnson willed her native costume to the Vancouver Museum. Chiefswood, restored and opened as a museum for the centenary of her birth in 1961, preserves manuscripts of some of her poems and other artefacts. Her correspondence with J. Walter McRaye, manuscripts of several poems and stories, and clippings, programs, and cards relating to her recitals are held by the McMaster Univ. Library, Div. of Arch. and Research Coll., Hamilton, Ont. Letters to lawyer Arthur Henry O’Brien and some manuscript poems are in the Lorne and Edith Pierce Coll. of Canadian mss at QUA. Other sources for her life are documented in B. [C.] Keller, Pauline: a biography of Pauline Johnson (Vancouver and Toronto, 1981). A contemporary native response is Joan Crate, Pale as real ladies: poems for Pauline Johnson ([Ilderton, Ont.], 1989).

Sara Jeannette Duncan’s interview with Pauline Johnson was published in the Globe on 14 Oct. 1886 in “Garth Grafton”’s column “Woman’s world.” Johnson’s essay “A strong race opinion on the Indian girl in modern fiction” appeared in the Sunday edition of the paper on 22 May 1892.

Marilyn Beker, “Pauline Johnson: a biographical, thematical and stylistic study” (ma thesis, Sir George Williams Univ. [Concordia Univ.], Montreal, 1974). B. C. Keller, “On tour with Pauline Johnson,” Beaver, 66 (1986–87), no.6: 19–25. Elizabeth Loosley, “Pauline Johnson, 1861–1913,” in The clear spirit: twenty Canadian women and their times, ed. Mary Quayle Innis (Toronto, 1966), 74–90. G. W. Lyon, “Pauline Johnson: a reconsideration,” Studies in Canadian Lit. (Fredericton), 15 (1990): 136–59. [J.] W. McRaye, Pauline Johnson and her friends (Toronto, 1947). Marcus Van Steen, Pauline Johnson: her life and work (Toronto, 1965). J. H. Waldie, “The Iroquois poetess: Pauline Johnson,” OH, 40 (1948): 67–75.

Cite This Article

Marilyn J. Rose, “JOHNSON, EMILY PAULINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/johnson_emily_pauline_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/johnson_emily_pauline_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marilyn J. Rose |

| Title of Article: | JOHNSON, EMILY PAULINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |