MOONEY, HELEN LETITIA (McClung), teacher, social reformer, author, politician, and office holder; b. 20 Oct. 1873 near Chatsworth, Ont., daughter of John Mooney and Letitia McCurdy, farmers; m. 25 Aug. 1896 Robert Wesley McClung in Wawanesa, Man., and they had four sons and a daughter; d. 1 Sept. 1951 in Saanich, B.C.

Nellie L. Mooney was the youngest of six children. Her Methodist father had immigrated from County Tipperary (Republic of Ireland) to Upper Canada in 1830 and worked as a shantyman in Ottawa River lumber camps; he settled in 1841 on a free-grant farm of 50 rocky acres near Chatsworth, south of Georgian Bay, and married Letitia McCurdy, a Scottish-born Presbyterian 20 years his junior. Nellie’s autobiography describes them as good Christians who valued hard work, education, rural life, and discipline. She loved her father’s Irish wit and light-heartedness and admired her mother’s determination and sense of personal duty, if not her strict Calvinist approach to life.

In 1880 the family joined the migration of land-hungry farmers to the prairies, in their case by steamship, ox-cart, and foot to the Souris River valley in Manitoba. After rejecting land that might have involved uncomfortably close contact with Métis neighbours, they chose an isolated holding southwest of Portage la Prairie, near Millford. Life there was demanding, yet the holding proved more prosperous than the farm in Ontario. Nellie’s childhood, colourfully captured in her autobiographic Clearing in the west ... (1935), unfolded in an affectionate Methodist family that took for granted its right to displace natives and Métis and create a dominant British community. Her escape from the demands of farming was the prairies, where, she recalled, she was free to “run wild” before attending school at age nine. A close reading of her autobiography, however, suggests that chores and parental efforts to control a strong-willed daughter curbed her range. Still, she would always cherish her experience as a homesteader and would draw, in her writing, on memories of “the cold road” and “hair frozen to the bedclothes at night” to explain her empathy for rural women. First exposed at a community picnic to drunkenness, an abiding theme in her life’s work, she quickly agreed with her mother that liquor was “one of the devil’s devices for confounding mankind.” Ultimately, as historian Pierre Berton* would observe, “she was a product of the prairies, as Western as Red Fife.” She was not only prairie educated but also prairie schooled. Initially a reluctant learner, she studied hard and with pleasure for six years at the Northfield school near Millford under teacher Frank Schultz. Nellie later credited him with encouraging her ambition. He also helped her question settlers’ dispossession of the natives and Métis. During children’s re-enactments, her choice to play Poundmaker [Pītikwahanapiwīyin*], a Cree leader in the North-West rebellion of 1885, foreshadowed sympathy with, but no real comprehension of the problems of, Canada’s First Nations, whom she, like most white Canadians of her day, saw as a dying race. Literature soon joined prairie history and landscape as inspiration. The written word, beginning with the Ontario readers, Collier’s History of England, and the Family Herald and Weekly Star (Montreal), offered companionship and guidance.

In 1889 Nellie entered the Winnipeg Normal School to attain a second-class teaching certificate, one of the few professional options for women. The school fed her thirst for more literature. After reading Charles Dickens’s novel The life and adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, she “knew in that radiance what a writer can be at his best, an interpreter, a revealer of secrets, a heavenly surgeon, a sculptor who can bring an angel out of a stone.” Her lifelong restiveness with authority was also fuelled by a faith that books, or more broadly education, illuminated the oppression of ordinary people and offered a tool for liberation.

Her adult life and teaching career began in 1890 at Hazel school near Manitou, Man., where she taught all eight grades. Paid employment would last five years, in four different schools in south-central Manitoba. She started off with some controversy: she introduced football for girls as well as boys, in order to foster fair play and discipline, and she dramatized alcohol’s destructive effects with a temperance chart. Both initiatives sparked parental protest, which she controlled with the good humour and diplomacy that would later serve her so well. The young teacher matured rapidly, sharpening her politics and extending her network of friends. In 1892 she took a job at the Manitou school and boarded with the family of Methodist minister James Adam McClung. She was impressed with his wife, Annie E., a leader in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and an ardent champion of women’s suffrage, and soon joined in her agitations. Nellie’s growing affection and profound respect for Mrs McClung directly influenced her decision to marry into the family. A romance developed with their second son, Wesley, a pharmacy student. Her horizons were further broadened in 1894 by six months at the Winnipeg Collegiate Institute, where she gained an Isbister Scholarship and a first-class certificate. She then took a post at the school in Treherne, once again boarding with the McClungs, who had relocated there; in 1895 she returned as a teacher to Northfield and lived with her widowed mother. The following year she married Wesley McClung and settled in Manitou, where he ran a drugstore. Certain in her choice, she wrote “I knew I could be happy with Wes.... I would not be afraid of life with him.” Though forced by convention to give up her job upon marriage, she would remain an educator for the rest of her life.

Nellie’s second autobiographical volume, The stream runs fast ... (1945), captures her married life and full engagement in reform. A secure member of the middle class as the wife of Manitou’s druggist, she revelled in social activism, authorship, politics, and child rearing. Raised to view women as equals, Wesley offered full support. Something of a “new man,” he quietly championed feminism as critical to community betterment. The births of John Wesley (Jack) (1897), Florence (1899), Paul (1900), Horace Barrie (1906), and Mark (1911) brought joy and additional work. Nellie almost always had hired help, usually young immigrant (often Finnish or Ukrainian) women. She would identify many as friends, sometimes portray them in her writing, and present good, some might say paternalistic, relations as one way to assimilate newcomers. The arrival of babies also furthered the goals of feminism. As a child, Nellie had resented the fact that “it was the women who were responsible for everything” and questioned the “Old-World reverence for men” demonstrated by her mother and others. Horrified by the physical complaints of her first pregnancy, she turned to maternalism, an ideology that treated women not as victims of nature but as blessed beings with a divine purpose. Reverence for motherhood, a popular dogma of her age, strengthened her growing critique of gendered injustice and her sense of women’s solidarity.

Nellie argued in her autobiography that “women must be made to feel their responsibility. All this protective love ... must be organized in some way, and made effective.” Determined in Manitou not to become “the most deadly uninteresting person and the one who has the greatest temptation not to think at all[,]... the comfortable and happily married woman,” the young mother fought complacency. With practical support from her mother-in-law and hired help, she forged a life beyond the home. In 1902, under pressure from Annie McClung, she entered a short-story contest for Collier’s, a leading American family magazine. Although not a winner, her composition became the initial chapter of her best-selling novel Sowing seeds in Danny (1908), the first of a trilogy based on the feisty character of Pearl Watson. Like her maker, this young British settler upset conventions. In The second chance (1910) and Purple Springs (1921), she targeted everything, including the battering of wives and children, laws against women, single motherhood, the need for day-care centres, prairie isolation, Calvinist guilt, the hoarding of money, and allowing Indians to be rooted in their own cultures. As a heroine, Pearl belongs with Lucy Maud Montgomery*’s Anne Shirley and such American characters as Pollyanna and Elsie Dinsmore. Sowing goodness and dispelling ignorance, she offered an attractive vision of small-town and rural Protestant youth.

Like her star, Nellie espoused a strong sense of Christian duty as a responsible householder and community volunteer. She was active in Manitou’s WCTU, Methodist Ladies’ Aid, Home Economics Association, Epworth League (a Methodist youth organization), Band of Hope (the WCTU children’s group), and Methodist Sunday school. She also enjoyed the travelling entertainers who brightened life before radio and film. With Wesley, she “got into every attraction that, in the early nineties, ever took to the road.” On one occasion she met Canada’s leading native performer, critic, and writer, Emily Pauline Johnson*, who would become a devoted friend.

In the WCTU, with its goal of sober improvement superintended by responsible women, Nellie felt most able to tackle inequality. Like other feminists, she found Canada’s largest women’s organization a source of political growth and friendship. At a WCTU convention in 1907 in Manitou, when she endeavoured to arouse support or “fire the heather,” she “felt the stirrings of ambition to be a public speaker.” Retrospectively she asserted, “It is quite likely that there is no person else who remembers that speech, but I remember it.... For the first time I knew I had the power of speech. I saw faces brighten, eyes glisten, and felt the atmosphere crackle with a new power.” As a highly popular author and fiery speaker, she was in demand around the province. Although chastised for spending time away from her children, she believed respectable motherhood was entirely compatible with outside work, paid and unpaid.

During her travels, and as a wife and mother, Nellie furthered her critical awareness of the social, economic, and political changes engulfing Canada. Immigration, especially from eastern and southern Europe, brought a new ethnic mix that caused her simultaneously to fear the future and to sympathize with the dispossessed. She identified male privilege as central to many problems, including family desertion, alcoholism, the appropriation of wives’ wages, domestic violence, custody battles, and farm-women’s isolation. A deeply religious and socially concerned Methodist, she joined enthusiastic Manitoba apostles of the Social Gospel (the belief that Christianity demanded social, not just individual, reform), among them James Shaver Woodsworth*, the superintendent of All Peoples’ Mission in Winnipeg, and Ella Cora Hind*, a reporter and suffragist, in questioning much of the status quo. Part of a close-knit progressive alliance, she increasingly looked to the state to remedy abuses.

When Wesley accepted a position with the Manufacturers Life Insurance Company in 1911, the McClungs moved to Winnipeg. Nellie was welcomed as a seasoned crusader by the booming capital’s established reformers. Even while producing a new collection of stories, The Black Creek Stopping-House ... (1912), she found time to absorb her surroundings. Winnipeg exposed her to the problems of rapid urban development; industrial exploitation, homelessness, and violence deepened her social conscience. Within a short time, the provincial Conservative government of Rodmond Palen Roblin* found her a force to be reckoned with. The weekly meetings of the Canadian Women’s Press Club provided an early platform. Here the germ for an organization devoted to women’s right to vote was planted: “It was not enough for us to meet and talk and eat chicken sandwiches and olives. We felt we should organize and create a public sentiment in favour of women’s suffrage.” The visit in 1911 of British feminist Emmeline Pankhust spurred awareness of international movements. Nellie also worked with the Local Council of Women, which campaigned for a female factory inspector to protect women workers. Nellie and Mrs Claude Nash, a friend of Roblin, took the recalcitrant leader through Winnipeg’s deplorable factories, but to no avail. His refusal confirmed the need for a new politics.

Together with other educated middle-class activists, including Hind, Lillian Kate Thomas [Beynon*], her sister Francis Marion Beynon, Winona Margaret Dixon [Flett*], and Dr Amelia Yeomans [Le Sueur*], in early 1912 Nellie founded the Political Equality League, recognized by historian Catherine Lyle Cleverdon as “one of the most enterprising and successful suffrage organizations in the dominion.” Although primarily concerned with the vote, the league’s diverse membership, gathered from the WCTU, labour’s ranks, and the progressive Icelandic community, also embraced Prohibition and reforms in women’s legal status and labour law. When crusading for the PEL, Canada Monthly (London, Ont.) would report in 1916, Nellie was “as vivid as a tiger lily at a funeral.” A highpoint in the campaign was her leading role in The women’s parliament, a play organized by the PEL and performed at Winnipeg’s Walker Theatre. This remarkable satire was a strategic response to the league’s abortive attempt to get Manitoba’s Legislative Assembly to act on a massive suffrage petition. In the legislature on 27 Jan. 1914, Roblin “never had a closer listener in all his life” than Nellie, who became the perfect mimic as she memorized his arguments and affectations. On stage the next evening, in an all-female assembly in an imagined province where men were denied suffrage, she played the premier, patronizing a male delegation and rejecting men’s appeal for the franchise, joint guardianship of children, and economic independence. Newspapers reported merriment and applause as the arrogant premier met his comeuppance.

When a provincial election was called for July, Nellie became the unofficial leader of the franchise cause. Like many progressives, she was suspicious of partisan politics and resolved to fight on her own terms. She nonetheless addressed many meetings for the Liberals, who endorsed suffrage. Branded by the media as “the heroine of the campaign” and a “Canadian Joan of Arc,” she was burned in effigy in Brandon by the Conservatives. Little wonder Nellie remembered the campaign as “full of excitement – meetings, interviews, statements, contradictions, and through it all the consuming conviction that we were making history.” The Liberals did not win, but suffrage was clearly centre stage. In 1915 the Conservatives were beaten and a year later Manitoba became the first province to enfranchise women.

By the late summer of 1914 Nellie had been shocked by the prospect of war, concerned for the fate of both civilization and her 17-year-old son, Jack. Although she endorsed peace efforts, she nevertheless believed that a despotic and patriarchal Germany should be defeated. Her support strained relationships with pacifist friends such as the Beynons. In December, on account of Wesley’s work, the family moved, this time to Edmonton, the “Gateway to the North.” Nellie immediately found her place, becoming an influential member of the Equal Franchise League, the organization responsible for delivering a suffrage petition with 12,000 signatures to Liberal premier Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton*. She joined forces with prominent feminist Emily Gowan Murphy [Ferguson*]. She became the honorary president of the Edmonton Women’s Institute and the Methodist Woman’s Missionary Society of Alberta, maintained her interest in the Women’s Canadian Club, and joined the Red Cross and the Canadian Patriotic Fund. As well, she continued to be a popular lecturer. In October 1915 Toronto’s largest halls and churches could not accommodate the crowds eager to witness her “quintessentially Western energy.”

In 1915 her best-known volume, In times like these, was published. This tour de force, a mixture of wit, satire, good humour, and common sense, assembled PEL speeches, wartime addresses, and feminist and temperance arguments. Suffrage was firmly linked to Prohibition: enfranchised women would support temperance and sweep away many moral and social tragedies. Appearing before the Alberta legislature in 1915 as part of a large suffrage delegation, Nellie asserted “our plea is not for mercy but for justice.” She was rewarded. Temperance forces won the provincial referendum on liquor on 15 July; by the next year the sale of alcohol was outlawed. On 6 March 1916 the Alberta legislature agreed that women should have the right to vote. The bill received royal assent on 19 April, by which time the neighbouring province of Saskatchewan had extended the right to women.

Nellie’s son Jack had enlisted in the summer of 1915. In despair, she would write The next of kin ... (1917) in tribute. In 1916 she spent six weeks, her longest lecture tour, speaking in the United States for the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Her openness about her feelings as a soldier’s mother brought the war home to many Americans. During a second tour, in 1917 after America had joined the conflict, she found audiences keen for advice on comforting their boys. By 1918, when she published Three times and out, told by Private Simmons, Nellie was convinced that women should join in plans for post-war reconstruction. After writing to Unionist prime minister Sir Robert Laird Borden*, she and Emily Murphy were invited to Ottawa to join the Women’s War Conference of 1918, the first time the Canadian state officially consulted women. After World War I victory came on many fronts. Nellie welcomed her son’s safe return and celebrated progress for her sex: “Women have won as great a victory as the battle of Verdun!”

The post-war world, however, saw no consensus about the future among Canada’s progressive forces. Feminists divided among many camps – Communists, Conservatives, Liberals, Progressives, and proposed women’s parties. Distrustful of partisanship, Nellie always opposed a women’s party. Labour unrest grew as prices rose and jobs disappeared. Once again she again came into conflict with radical reformers, such as J. S. Woodsworth, who championed the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. A liberal, she was convinced that education and good will were sufficient, and revolution unnecessary, to usher in equality. Her sympathy for workers never stretched to include direct action. Strikes had their place but reform depended on working within the political system.

Nellie, who had supported suffrage-minded Liberals in elections in both Manitoba and Alberta, became a Liberal mla in 1921 for one of Edmonton’s five seats. The contest was marked by the unprecedented entry of eight female candidates. The progressive-minded United Farmers of Alberta formed the government and the Liberals were reduced to the opposition. In the legislature, Nellie regularly acted as an independent. As she said, “I believed that we were the executive of the people and should bring our best judgement to bear on every question, irrespective of party ties.” On women’s issues she joined forces with cabinet member Mary Irene Parlby [Marryat*]. They agreed on the need for travelling libraries, medical and dental clinics, public-health nurses, birth control, and eugenic legislation to limit the fertility of the mentally unfit. Nellie’s hopes for a revitalized community were also voiced in new publications: The beauty of Martha (1923), When Christmas crossed “The Peace” (1923), and All we like sheep ... (1926).

While in office she pushed for enforcement of the liquor laws. In 1923 the province, responding to public pressure, repealed Prohibition and endorsed government sale. In the same year Nellie moved to Calgary, where Wesley had been transferred and where she again ran for provincial office in 1926. Defeated, apparently because of her support for Prohibition, she felt betrayed by female voters. Writing new collections of short stories – Be good to yourself ... (1930) and Flowers for the living ... (1931) – offered consolation. In 1930 Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* asked her to run federally in Calgary against Conservative leader Richard Bedford Bennett*, but she declined and would never again test the electorate.

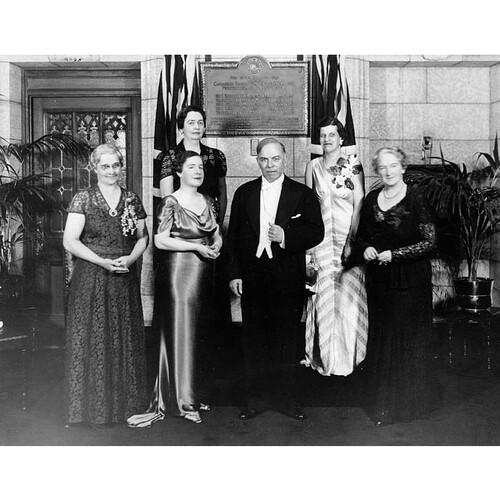

Nellie nonetheless remained an activist. She joined the fight led by Emily Murphy for the appointment of women to Canada’s Senate. In 1927, along with Murphy, Irene Parlby, former Alberta mla Louise McKinney [Crummy*], and National Council of Women of Canada vice-president Henrietta Louise Edwards [Muir*], she asked if “qualified persons,” in the section of the British North America Act dealing with appointment, included women. The following year the Supreme Court of Canada declared that women were not persons and hence not eligible, but the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ruled favourably in October 1929 on the appeal of the Famous Five, as Nellie and the others became known.

Church work also remained important. In 1921 she became the first woman sent by the Methodist Church of Canada to the Ecumenical Conference in London, England. Membership in the United Church of Canada (created by the union of Methodist, Presbyterian, and Congregational churches in 1925) included a struggle for female ordination, eventually realized in 1936. After serving as the first female member of the board of governors of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation from 1936 to 1942, the westerner challenged her church to experiment with radio, “the greatest university.” The uncertain prospects of continuing peace during the inter-war years kept her attentive to international events and movements, including the Women’s Guild of Empire in England, the Oxford Group, and Moral Re-armament. During that period Leaves from Lantern Lane (1936) and More leaves from Lantern Lane (1937) underlined her interest in world affairs, her commitment to women’s rights and social reform, and her hostility to apathy and corruption.

The McClungs had moved in 1932 to Victoria, in Wesley’s final transfer. He retired a year later and in 1935 they bought a small farm nearby, which they christened Lantern Lane. Even then Nellie remained busy. Appointed a Canadian delegate to the League of Nations in 1938, she sat on the Fifth Committee addressing social issues, especially those concerned with women and children. During World War II, she ruffled many sensibilities by opposing the internment of Japanese Canadians. In 1945 she published The stream runs fast, her last book. She died on 1 Sept. 1951 at age 77 and was buried in Victoria’s Royal Oak Burial Park Cemetery.

Nellie L. McClung has received significant public and critical recognition. In 1938 Prime Minister King honoured the Famous Five with a plaque outside the Canadian Senate. A postage stamp featuring McClung’s picture marked her 100th birthday in 1973 and two years later her Manitou residence received commemorative recognition. On 18 Oct. 1999, the 70th anniversary of the final judgement in the persons case, bronze statues of McClung, Edwards, Parlby, Murphy, and McKinney were unveiled in Calgary’s Olympic Plaza. Replicas were placed on Parliament Hill in October 2000, the first sculptures of Canadian women to appear there. Her written work, 17 books and numerous stories and articles in magazines and newspapers, achieved much popularity during her lifetime but was also criticized as didactic. In response, she asserted in her autobiography that “I have never worried about my art. I have written as clearly as I could, never idly or dishonestly, and if some of my stories are ... sermons in disguise, my earnest hope is that the disguise did not obscure the sermon.” Post-suffrage commentary placed the charismatic McClung favourably within the history of the expansion of democracy and the curbing of male privilege. Modern analysis is more measured. Reappraisals cast her as a forerunner to modern Canadian authors such as Jean Margaret Laurence [Wemyss*], but many scholars now find her ideology insufficiently inclusive, given her assumption of Anglo-Celtic and middle-class leadership, her blind spots about native and non-British peoples, her sympathy for eugenics, and her Christian maternalism. Her contribution to a wide range of important causes and a literary legacy that conveys a generous spirit nevertheless continue to make Nellie L. McClung the most famous of Canada’s suffrage generation.

Nellie Letitia McClung’s Clearing in the west: my own story (Toronto, 1935) and The stream runs fast: my own story (Toronto, 1945) have been combined into a single volume, Nellie McClung, the complete autobiography ..., ed. Veronica Strong-Boag and M. L. Rosa (Peterborough, Ont., 2003). Aside from her autobiographical works, McClung was a prolific author in other genres, mainly novels and short stories. Some of her other works include: Sowing seeds in Danny (New York, 1908), The second chance (Toronto, 1910), The Black Creek Stopping-House and other stories (Toronto, 1912), In times like these (Toronto, 1915), The next of kin: those who wait and wonder (Toronto, 1917), Three times and out, told by Private Simmons (Toronto, 1918), The beauty of Martha (London, 1923), When Christmas crossed “The Peace” (Toronto, 1923), Painted fires (Toronto, 1925), All we like sheep and other stories (Toronto, 1926), Be good to yourself: a book of short stories (Toronto, 1930), Flowers for the living: a book of short stories (Toronto, 1931), Leaves from Lantern Lane (Toronto, 1936), and More leaves from Lantern Lane (Toronto, 1937). McClung’s Purple Springs (Toronto, 1921) was reissued in the same city in 1992 with an introduction by R. R. Warne. Another new edition of her work, edited and introduced by M. I. Davis, is Stories subversive: through the field with gloves off – short fiction by Nellie L. McClung ([Ottawa], 1996).

Unfortunately, McClung’s papers are quite limited and largely concerned with her literary career and the reminiscences of others. The three significant collections are: B.C. Arch. (Victoria), MS-0010; Univ. of Victoria Libraries, Special Coll., SC263; and Library and Arch. Canada (Ottawa), R4200-0-9.

H. M. Buss, Mapping our selves: Canadian women’s autobiography in English (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1993). C. L. Cleverdon, The woman suffrage movement in Canada, intro. Ramsay Cook (2nd ed., Toronto, 1974). Janice Fiamengo, “A legacy of ambivalence: responses to Nellie McClung,” in Rethinking Canada: the promise of women’s history, ed. Veronica Strong-Boag et al. (4th ed., Toronto, 2002), 149–63; “Rediscovering our foremothers again: the racial ideas of Canada’s early feminists, 1885–1945,” Essays on Canadian Writing (Toronto), 75 (winter 2002): 85–117. M. E. Hallett and M. I. Davis, Firing the heather: the life and times of Nellie McClung (Saskatoon, 1993). C. S. Savage, Our Nell: a scrapbook biography of Nellie L. McClung (Saskatoon, 1979). Veronica Strong-Boag, “Ever a crusader: Nellie McClung, first-wave feminist,” in Rethinking Canada: the promise of women’s history, ed. Veronica Strong-Boag and A. C. Fellman (3rd ed., Toronto, 1997), 271–84. Veronica Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson, Paddling her own canoe: the times and texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) (Toronto, 2000). R. R. Warne, Literature as pulpit: the Christian social activism of Nellie L. McClung (Waterloo, Ont., 1993).

Cite This Article

Michelle Swann and Veronica Strong-Boag, “MOONEY, HELEN LETITIA (McCLUNG),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 31, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mooney_helen_letitia_18E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mooney_helen_letitia_18E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michelle Swann and Veronica Strong-Boag |

| Title of Article: | MOONEY, HELEN LETITIA (McCLUNG) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2009 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | January 31, 2026 |