Source: Link

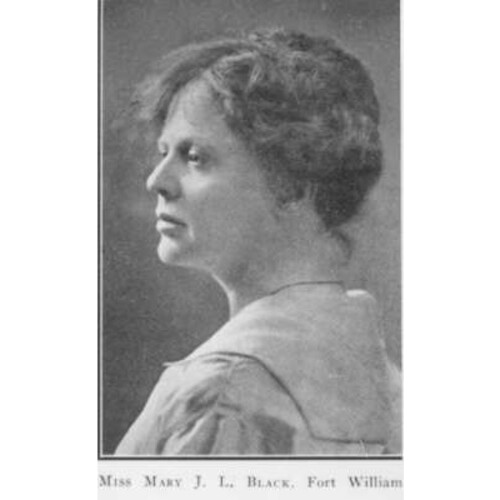

BLACK, MARY JOHANNA LOUISA, librarian; b. 1 April 1879 in Uxbridge, Ont., daughter of Fergus Black and Georgina Elizabeth Macdonald; d. unmarried 4 Jan. 1939 in Vancouver.

A self-described “Scotchwoman,” Mary Johanna Louisa Black was named for her grandmothers and a maternal great-grandmother. Her grandfather William Black emigrated from Carlisle, England, to Ontario County, Upper Canada, in the 1840s, while Roderick Macdonald, her mother’s father, moved from Nova Scotia to Oxford County about the same time; both were teachers. Her father, Fergus, eventually became a teacher as well, holding posts in Barrie, Listowel, and Guelph. In 1879 he qualified as a physician and practised in the townships of Reach (Scugog), Uxbridge, and Humberstone (Port Colborne), and in Springfield (Elgin County). Described as “a man of wide literary achievement and all-round culture,” Dr Black, a widower by 1900, “took an immense interest in the education and mental development” of his only daughter, whose four siblings were also high achievers. Mary’s intellectual ability is evident in her writings on libraries and in a recollection she published of walks and talks with the poet William Wilfred Campbell*, who was married to her first cousin. Her brother Norman Fergus Black, who graduated d.paed. from the University of Toronto in 1913, would become a notable author and educator in Saskatchewan and British Columbia. He influenced his sister’s approach to children and libraries, and to the Canadianization of non-English-speaking immigrants, just as she influenced his contribution to the British Columbia Public Library Commission.

Little is known about Mary’s life before September 1907, when she and her father arrived in Fort William (Thunder Bay) from Springfield to live with her brother Davidson William, who had left banking and mining to enter the grain business at the Lakehead. Her father continued to practise medicine. Within two years, without a university education or formal training, Mary J. L. Black was hired to run the public library. It was located in the basement of the city hall, where book-lending services for Canadian Pacific Railway employees and the local citizens had been amalgamated. Black began work on 1 Jan. 1909 at a salary of $40 a month. This “accidental librarian,” as she would be dubbed in a 1931 magazine profile, was fortunate to be in a rapidly growing city whose council and library board had the drive and vision needed to secure $50,000 from American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to erect an impressive new building, which opened in April 1912.

Black soon turned Fort William’s library into an oasis of culture in a city that was ethnically diverse and mainly working class. Believing that the ideal librarian has “a love of people,” she set herself the goal of creating a service-oriented institution “that helps develop intelligence and ideals among our citizens,” more practically “to carry the right book to the right reader at the least cost.” By 1917 annual circulation had reached 90,000 volumes, or five books per capita, a remarkable achievement for a city of relatively low levels of education. She forged links with schools and teachers, and under her leadership reference services were emphasized, which included the introduction of telephone enquiry. She developed a collection that a successor, Lachlan Farquhar MacRae, would call “astonishing.” Not only did she promote Canadian authors and children’s books, but, unusually for the time, she also displayed the work of national and local artists; several paintings were by the Group of Seven. The library was often a stop for touring celebrities such as writer Helen Letitia McClung [Mooney*] and poet William Bliss Carman*.

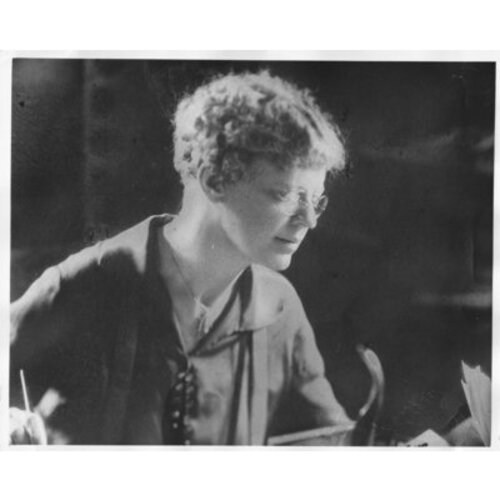

By 1913 Black had become a councillor of the Ontario Library Association and in 1917 she was named its first woman president. That year she was also an instructor at the library-training school run by the Department of Education in Toronto. She held many positions in the American Library Association, which represented members from both the United States and Canada [see William Oliver Carson*]. After she was named chair of its lending section in 1926, institutions began writing to her for advice on what books to buy. By 1930 she was so well regarded that she was asked to join John Ridington, librarian of the University of British Columbia, and George Herbert Locke, head of the Toronto Public Library, in conducting an inquiry into library conditions and needs in the country. Funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, it was the first report of its kind in Canada.

Black’s closest friends were intelligent professional women – teachers, social workers, and nurses, including Ethel Johns* – and she contributed to the work of several women’s organizations, serving as president of the Fort William branch of the Women’s Canadian Club (1916–18) and the Women’s Business Club (1921). In addition she was a member of the West Algoma Equal Suffrage Association. From 1913 to 1928 Black was the administrative mainstay of the Thunder Bay Historical Society (TBHS), fulfilling the duties of secretary-treasurer and taking on responsibility for the society’s archives and the publication of its annual volumes; she was the TBHS president from 1928 to 1932. She also did work for the Presbyterian and, after 1925, United churches, acted as district commissioner of the Girl Guides, and sat on the board of a regional music festival.

In January 1918 Black was elected a school trustee, having been endorsed by the Canadian Women’s Press Club and the West Algoma Council of Women because, as the Fort William Daily Times-Journal (3 Jan. 1918) reported, she “unites good sense … and kindly sympathy with the women and girls of today, allied with a delightful sense of humor that helps to preserve the just proportion of things.” Re-elected in 1920, at a time of unemployment and economic depression, she fought a series of frustrating battles against male trustees in defence of raising the salaries of women teachers; against the arbitrary dismissal of one of her friends, a female high-school classics teacher; and against eliminating school dental services and dropping domestic science and manual training. When playgrounds were threatened by a lack of city financing, she proposed a system of volunteer assistance to keep them going. An active Liberal, Black worked across party lines to support local candidate Robert James Manion* in 1917 when he sought the federal seat as a Unionist [see Sir Robert Laird Borden] and again in 1921 when he ran as a Conservative. However, her idealism and enthusiasm for political action dimmed after these interventions.

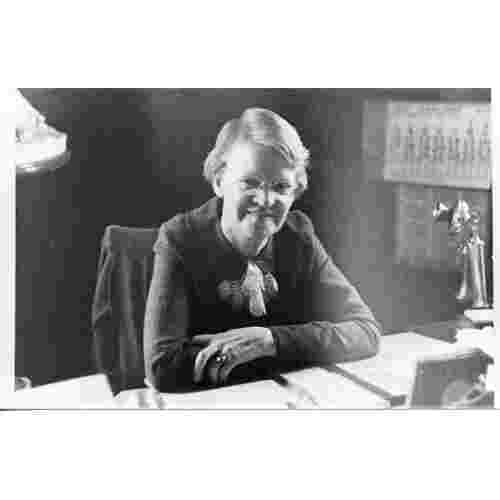

Bereft of her brother Davidson, who had died in 1918, and her father, who died in 1933, Black had to face the grim years of the Great Depression alone. She was then earning a salary of $160 a month. She had achieved what she could in more prosperous times, and when her health began to fail she resigned on 1 May 1937 and moved to Vancouver to live with her brother Norman. After more than 28 years of continuous service, she was awarded a monthly pension of $50. Fort William honoured her significance to the community in 1938 when it named its new Westfort branch library the Mary J. L. Black Public Library. As the local newspaper stated, its citizens were proud that their librarian had exerted influence beyond “the narrow confines of one small city.” She died the following year after suffering a stroke.

Although Mary J. L. Black made no original contribution to library work, she is the exemplar of what can be achieved in a small cultural institution by force of character and dedication. A self-described “good listener,” possessed of an engaging personality, a sense of humour, and a passion for learning, she was beloved by all her patrons, young and old. Thanks to her tact and leadership skills, she commanded the respect of persons who were not her intellectual equals, inspired the politicians and citizens of Fort William to support the expansion of library services beyond mere book lending, and impressed her peers throughout North America. In a 1964 interview British Columbia library pioneer and advocate Helen Gordon Stewart recalled that “never yet, in all the libraries I have visited, did I see a library which I thought did the job for its community that Mary Black’s library in Fort William did.”

Mary Johanna Louisa Black is the author of “Our public library,” Thunder Bay Hist. Soc., Papers ([Fort William [Thunder Bay], Ont.]), 1911–12: 6–7; “Town survey: in theory and in practice,” Ont. Library Assoc., Proc. of the fifteenth annual meeting (Toronto, 1915), 72–80; “The library and the girl,” Ontario Library Rev. (Toronto), 1 (June 1916–May 1917): 8–9; “What seems to me an important aspect of the work of public libraries at the present time,” Ont. Library Assoc., Proc. of the seventeenth annual meeting (Toronto, 1917), 30–34, revised and published as “An important aspect at the present time,” Public Libraries (Chicago), 22 (1917): 215–18; “Concerning some popular fallacies,” Ont. Library Assoc., Proc. of the eighteenth annual meeting (Toronto, 1918), 52–58, revised and published as “Concerning some library fallacies,” Public Libraries, 23 (1918): 199–204; “Walks and talks with Wilfred Campbell,” Ontario Library Rev., 3 (August 1918–May 1919): 30–31; “Twentieth century librarianship,” Canadian Bookman (Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Que.), January 1919: 58–59; “New library legislation in Ontario,” Canadian Bookman (Gardenvale, Que.), December 1920: 18–19; “The public library and national art,” Daily Times-Journal (Fort William), 12 Jan. 1921; “Early history of the Fort William Public Library,” Thunder Bay Hist. Soc., Annual report, 1924–25, 1925–26: 28–31; “Canadian library extension meeting,” American Library Assoc., Bull. (Chicago), 21 (1927): 338–40; “Adult education,” Ont. Library Assoc., Proc. of the twenty eighth annual meeting (Toronto, 1928), 61–64; “Ontario libraries,” Ontario Library Rev., 15 (August 1930–May 1931): 132–38; “Publicity for the older books,” Ontario Library Rev., 17 (February–November 1933): 5–6; “Fort William, Ontario, Public Library,” Library Journal (New York), 59 (1934): 510–11; and “The ideal librarian,” Ontario Library Rev., 19 (February–November 1935): 125–26.

Black was appointed to the three-person commission of inquiry, with George Herbert Locke and John Ridington, that produced Libraries in Canada: a study of library conditions and needs (Toronto and Chicago, 1933). The commission reported that four-fifths of Canadian citizens were without library service of any kind and recommended that responsibility for public libraries be vested in the provincial ministries of education. The writers advocated the creation of a national library, comparable to those in other countries, to provide leadership. While they could foresee the benefits of establishing a Canadian library association (not as a rival to the American body but in addition to it), it was not possible to sustain such an organization at that time.

A chronology of the subject’s life is on file at the DCB.

BCA, GR-2951, no.1939-09-552257. Private arch., F. B. Scollie (Ottawa), Letter from Eleanor Todd, 11 Feb. 1983. Daily Times-Journal, 1907–59. “Ft. William: its art development,” Christian Science Monitor (Boston), 5 Sept. 1921: 12. Morning Herald (Fort William), 1909–14. News-Chronicle (Port Arthur [Thunder Bay]), 1920–28. Vancouver Daily Province, 4, 6 Jan. 1939. Brook Abbott, “An accidental librarian: Mary Black of Fort William, Ont. governs the destinies of a library whose motto is hospitality,” Canadian Magazine, 76 (July–December 1931), no.5: 18, 29. As we remember it: interviews with pioneering librarians of British Columbia, ed. Marion Gilroy and Samuel Rothstein (Vancouver, 1970). L. [D.] Bruce, Free books for all: the public library movement in Ontario, 1850–1930 (Toronto, 1994). “The librarian and library of Fort William,” Ontario Library Rev., 1 (June 1916–May 1917): 92–95. T. M. Longstreth, The Lake Superior country (Toronto, 1924). J. R. Lumby, “Retirement of Miss M. J. L. Black from the Fort William Public Library,” Ontario Library Rev., 21 (February–November 1937): 132. Madge Macbeth, “A bookish person,” Canadian Magazine, 51 (May–October 1918): 518–20. Angus Mackay, The book of Mackay (Edinburgh and Madoc, Ont., 1906). “Mary J. L. Black dies in Vancouver,” Ontario Library Rev., 23 (February–November 1939): 5–7. Ken Morrison, “Mary J. L. Black of the Fort William Public Library,” Thunder Bay Hist. Museum Soc., Papers and Records, 11 (1983): 23–31. Eleanor Todd, Burrs and blackberries from Goodwood (Goodwood, Ont., 1980).

Cite This Article

Frederick Brent Scollie, “BLACK, MARY JOHANNA LOUISA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/black_mary_johanna_louisa_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/black_mary_johanna_louisa_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Frederick Brent Scollie |

| Title of Article: | BLACK, MARY JOHANNA LOUISA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |