Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

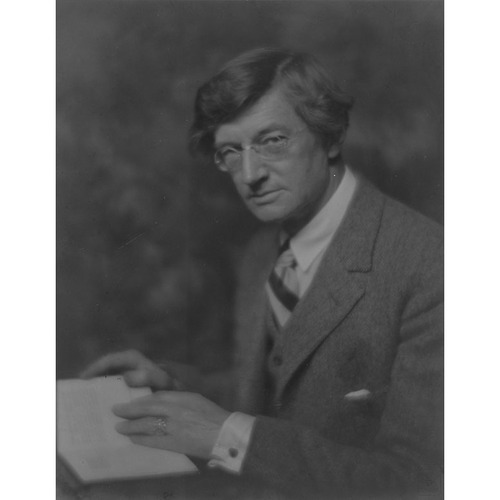

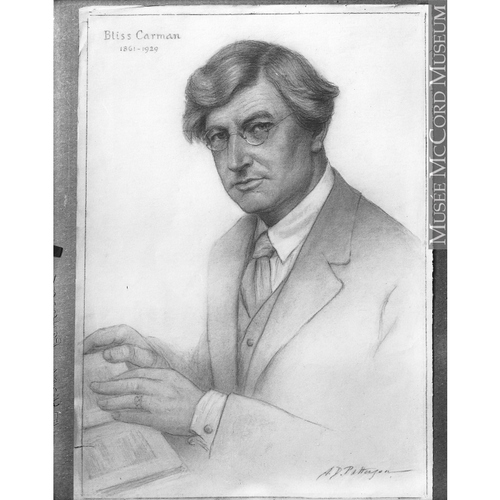

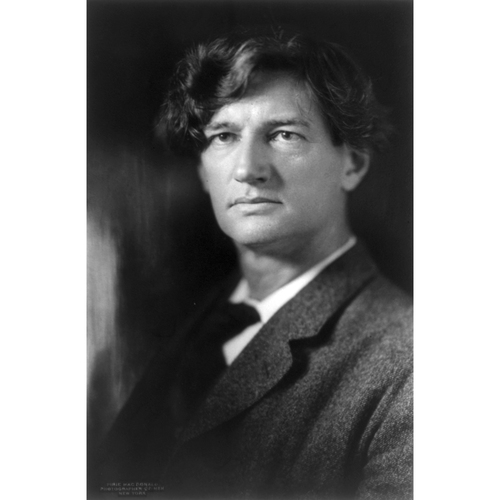

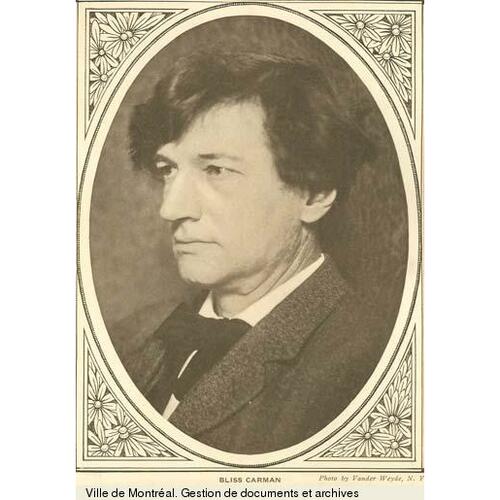

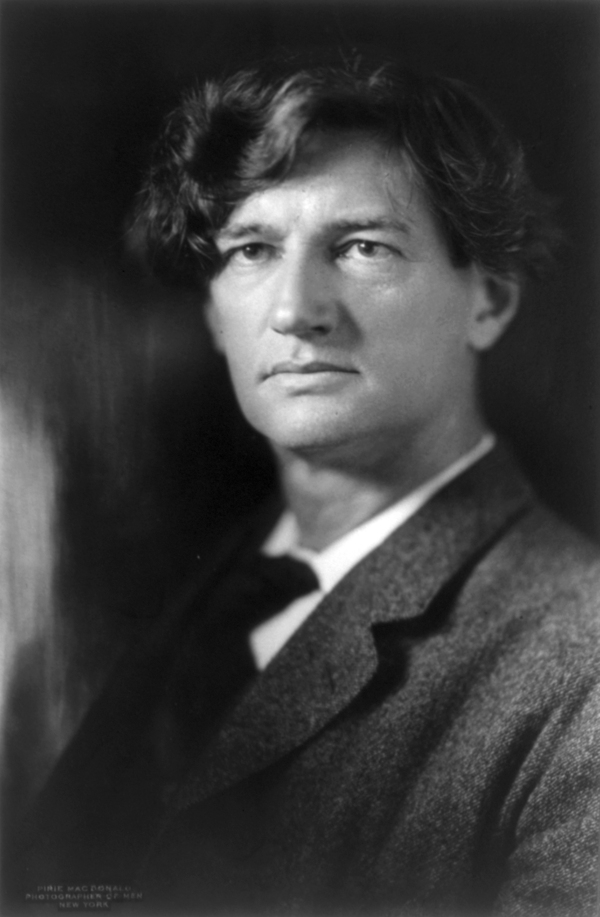

CARMAN, WILLIAM BLISS (he chose Bliss Carman as his authorial name in 1884), poet, essayist, journalist, and editor; b. 15 April 1861 in Fredericton, son of William Carman, a barrister and court official, and Sophia Mary Bliss; d. unmarried 8 June 1929 in New Canaan, Conn.

Bliss Carman, whose ancestors were loyalists, was educated at the Collegiate School in Fredericton, where George Robert Parkin was headmaster, and at the University of New Brunswick (ba 1881, ma 1884); he subsequently attended the University of Edinburgh (1882–83) and Harvard University (1886–87). After returning to Fredericton from Scotland in 1883, he had tried his hand at teaching, surveying, and the law, and had written reviews for the University Monthly, activities that reflected his restlessness and his journalistic bent. At Harvard, he was heavily influenced by Josiah Royce, whose spiritualistic idealism, combined with the transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson, lies centrally in the background of his first major poem, “Low tide on Grand Pré,” written in the summer and winter of 1886. After again returning briefly to the Maritimes in the late 1880s, he moved permanently to the United States, where he worked for two years (1890–92) as literary editor of the Independent (New York), the first of many similar positions on various American magazines. In 1894 he helped to found the Chap-Book (Boston), between 1895 and 1900 he wrote a weekly column for the Boston Evening Transcript, and in 1904 he published the ten volumes of The world’s best poetry (Philadelphia), of which he was editor-in-chief.

Even before his permanent removal to the United States in February 1890, Carman had begun, with the help of his cousin Charles George Douglas Roberts*, to establish a reputation for himself as an accomplished and promising poet. In 1893 he published his first collection of poems, Low tide on Grand Pré: a book of lyrics, and in ensuing years his gift for lyricism resulted in over twenty more books of poetry, including the three volumes of the Vagabondia series (1894-1900) that he co-authored with the American poet and essayist Richard Hovey. Under the tutelage, first of Hovey’s companion, Henrietta Russell, and then of the woman who became a major love of his life, Mary Perry King, he drew on the theories of François-Alexandre-Nicolas-Chéri Delsarte to develop a strategy of mind-body-spirit harmonization aimed at undoing the physical, psychological, and spiritual damage caused by urban modernity. By terms charmingly, orotundly, and fancifully expounded in such prose works as The kinship of nature (1903) and, with Mrs King, The making of personality (1908), his therapeutic ideas resulted in the five volumes of verse assembled in Pipes of Pan (1906), a collection that contains many superb lyrics but, overall, evinces the dangers of a soporific aesthetic. It was a combination of these concerns and the discipline of the Sapphic fragments that produced his finest volume of poetry, Sappho: one hundred lyrics (1903).

Like other members of the “confederation” group of Canadian poets (Roberts, Archibald Lampman*, William Wilfred Campbell*, Duncan Campbell Scott*, and Frederick George Scott*), Carman was lifted to fame in Canada by the wave of post-confederation nationalism and its accompanying call for a distinctive and distinguished Canadian literature. Outside the country, however, he was widely regarded not merely as a typical Canadian poet, but also as one of the most prominent American poets of the generation that was coming to maturity in the 1880s and 1890s. “I passed everywhere for a ‘young American writer,’” he told a correspondent after a trip to Paris in 1896; “I wept inwardly, but could not refuse the compliment.” His impact on American letters is suggested by the fact that in 1909 Wallace Stevens composed poems “to the accompaniment” of a line from Carman’s “May and June” and by his appointment as editor of The Oxford book of American verse (1927). Nor was Carman’s influence and reputation confined to North America: during the 1890s his work was well received by Arthur William Symons and other discerning British readers, and in 1904 Francis Thompson described him as “a Canadian poet of deserved repute this side the water, with a lusty and individualised joy in nature.”

Much of Carman’s writing in poetry and prose during the decade preceding World War I is as repetitive as the title of Echoes from Vagabondia (1912) intimates, but after the war (and after a battle with tuberculosis in 1919–20), he resumed his spiritual adventurousness under the influence of theosophy and other esoteric philosophical systems. During the war Carman had worked with a group of American writers to bring the United States into the conflict and in the years that followed he renewed his ties with Canada, which rewarded his loyalty in several highly successful reading and lecturing tours (1920-29) and in various honours, including corresponding membership in the Royal Society of Canada (1925) and the society’s Lorne Pierce Medal for distinguished service to Canadian literature (1928). It was during the first of his Canadian tours that he was unofficially dubbed the poet laureate of Canada. Four volumes of poems published in the 1920s, most notably Later poems (1921) and Far horizons (1925), reflect his spiritual and patriotic awakenings, as do Talks on poetry and life . . . (1926), a collection of lectures and readings delivered at the University of Toronto, and Our Canadian literature: representative verse, English and French (1935), an anthology completed after his death by Lorne Albert Pierce*. With another book of poetry (Wild garden) recently published and another (Sanctuary: Sunshine House sonnets) in preparation, Carman died of a brain haemorrhage on 8 June 1929 at New Canaan, where he had spent at least part of every year since 1897 in order to be near Mrs King. His ashes were buried in Forest Hill Cemetery, Fredericton, and a national memorial service was held at the Anglican cathedral there. Not until 13 May 1954 was he granted the wish that he had expressed in 1892 in “The grave-tree”: “Let me have a scarlet maple / For the grave-tree at my head, / With the quiet sun behind it, / In the years when I am dead.”

A major reason for the long delay in granting Carman’s wish was the shift in poetic taste that began with the triumph of modernism in Canada between the wars and led to the dismissal of such phrases as “scarlet maple” and “quiet sun” as sentimental and vague. The continuing underestimation of Carman is to be regretted, for at his best he is one of the finest lyricists that Canada has produced and several aspects of his thought, not least his belief in personal harmony and his reverence for external nature, will always have much to recommend them. “I have known few poets anywhere . . . who . . . so dedicated himself to the service of poetry as Bliss Carman,” wrote Padraic Colum in the prefatory note to Sanctuary. “His life had a frugal dignity which was in itself a rare and a fine achievement. The tweeds that he wore had given him long service; they were always carefully pressed and spotless; that wide-brimmed hat he had worn for many seasons. Yet there was always something in his attire that corresponded to the gaiety and color of his mind – a bright neck-tie, a silver chain, a turquoise ornament that some Indian friend had bestowed upon him. He was a tall man. But that exceptional build was contained in a thin integument. He bled easily; he was sensitive over every part of his great frame. However, that irritability that usually goes with the thin skin was no part of his nature. Bliss Carman was above everything else a sweet-natured man. I am sure that no one ever parted from him without thinking, ‘I hope I shall see dear Bliss Carman again.’” “He was like an old king from a fairy story,” added Margaret Lawrence, one of several women who had been devoted to him. “He spoke his words distinctly, giving them their due, as one who loved them dearly.”

Listings of the collections in which Bliss Carman’s letters are preserved are provided in Muriel Miller, Bliss Carman: quest and revolt (St John’s, 1985), and Letters of Bliss Carman, ed. H. P. Gundy (Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1981). Gundy’s edition also contains notes on the major Carman collections, which include the Bliss Carman fonds at QUA; the Bliss Carman papers at Neilson Library, Smith College (Northampton, Mass.); the Odell Shepard coll. and W. I. Morse Canadiana coll. in Harvard College Library, Houghton Library, Dept. of mss (Cambridge, Mass.); and material in the Baker/Berry Library, Dartmouth College (Hanover, N.J.) and in several collections in the Univ. of N.B. Library, Arch. and Special Coll. Dept. (Fredericton), among them MG L10 (C. G. D. Roberts fonds) and MG L32 (I. St. J. Bliss coll.). Bliss Carman’s letters to Margaret Lawrence, 1927–1929, ed. D. M. R. Bentley, assisted by Margaret Maciejewski (London, Ont., 1995), contains a particularly illuminating correspondence. “A primary and secondary bibliography of Bliss Carman’s work,” comp. J. R. Sorfleet, is available in Bliss Carman: a reappraisal, ed. and intro. Gerald Lynch (Ottawa, 1990), 193–204. Since the appearance of Sorfleet’s bibliography, the journal Canadian Poetry (London, Ont.) has published several articles on Carman’s poetry and impact.

Cite This Article

D. M. R. Bentley, “CARMAN, WILLIAM BLISS (Bliss Carman),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carman_william_bliss_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carman_william_bliss_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | D. M. R. Bentley |

| Title of Article: | CARMAN, WILLIAM BLISS (Bliss Carman) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |