Source: Link

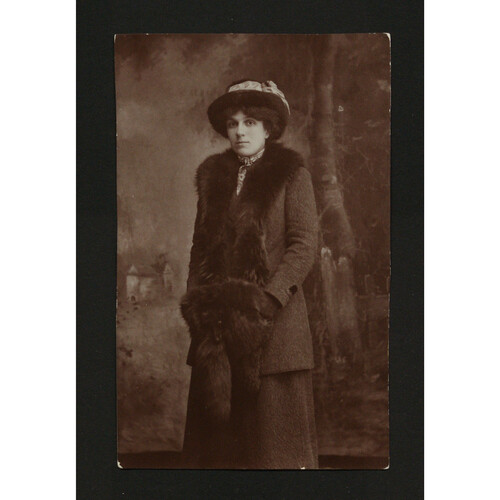

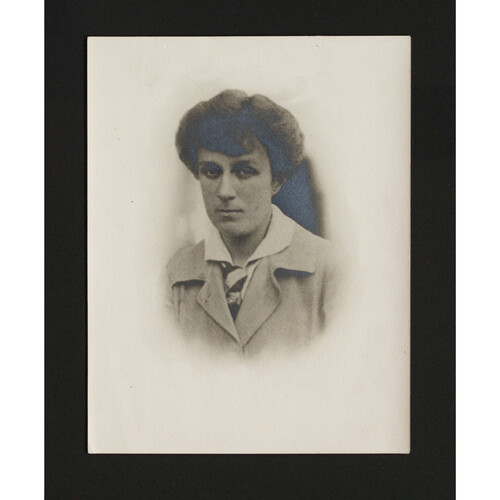

PICKTHALL, MARJORIE LOWRY CHRISTIE, author and librarian; b. 14 Sept. 1883 in Gunnersbury (London), England, daughter of Arthur Christie Pickthall, a surveyor, and Elizabeth Helen Mary Mallard; d. unmarried 19 April 1922 in Vancouver.

During her childhood in England, Marjorie Pickthall’s parents encouraged her artistic talents with gifts of books and lessons in drawing and music. In 1889 or 1890 the family immigrated to Toronto, where her father became a foreman at the city’s waterworks and later an electrical draftsman. Following the death of an infant brother in 1894, her parents again bestowed their attention on Marjorie as an only child. Summertimes, which were spent on the Toronto Islands, fostered in her a passion for country walks and habits of close observation. She developed her skills in nature description in the lively diaries she kept throughout her teens. While in the city she attended the Church of England day school on Beverley Street and, from 1899, Bishop Strachan School, where she excelled in composition and formed lasting friendships with other artistic young women. These activities were sometimes interrupted by her delicate health: she was plagued by headaches and later by dental, eye, and back problems.

In 1898, at 15, Pickthall had sold her first story to the Toronto Globe for $3. “Two-Ears” is about an Iroquois boy who wants to prove himself a warrior, and is typical of her later fiction: it draws on her imagination or reading about a distant culture and features a male protagonist straining against limits. Pickthall would often use Indian or French Canadian settings for her poetry and prose, as well as the medieval, biblical, and Celtic lore she absorbed from her favourite English poets: William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Fiona Macleod. “Two-Ears” and one of Pickthall’s poems won first prizes in the Daily Mail and Empire’s writing competition of 1899. In a different response to “Two-Ears,” James Cleland Hamilton sent her his pamphlet Famous Algonquins: Algic legends (Toronto, 1899), possibly as a corrective to her vilification of this First Nation. “I have ‘entered the literary world’ with a vengeance,” she recorded in her diary on 4 June 1900.

A regular contributor to the “Young people’s corner” of the Mail and Empire, Pickthall was also invited to write for the Globe’s “Circle of young Canada.” She won the Mail and Empire’s competition again in 1900 with “O keep the world for ever at the dawn,” a poem for the new century. With its Canadian inflection of the dream landscapes of late-19th-century aestheticism and its impassioned language and musicality, it attracted the attention of professors whose critical support would ensure Pickthall’s lasting reputation. Her rejection of modernism, including Henrik Ibsen’s “warped and distorted” work, and futurism’s abrasive forms represented continuity with the idealism of the “confederation poets” [see Joseph Edmund Collins*] and an alternative to the populist verse of such contemporaries as Robert William Service* and Thomas Robert Edward MacInnes.

Pickthall’s career began in earnest when prizes launched her into the magazines. “The greater gift” appeared in July 1903 in the first issue of East and West (Toronto), a young people’s journal sponsored by the Presbyterian Church. She became a regular contributor; three of her serials would appear in Toronto as books illustrated by Charles William Jefferys*: Dick’s desertion: a boy’s adventures in Canadian forests . . . (1905), The straight road (1906), and Billy’s hero; or, The valley of gold (1908). In a poetry competition in 1904 “The homecomers” had won third prize and the admiration of judge Oscar Pelham Edgar*, a professor at Victoria University in Toronto. He gave advice on her poems, which began appearing steadily in Acta Victoriana, and recommended her to the editor of the University Magazine, Andrew Macphail* of McGill University in Montreal, who featured her continuously from 1907. In 1913 he published 43 of her poems as The drift of pinions, which was successful both commercially and critically.

Not content to trust her literary affairs completely to the paternalistic professors who, she would later remark, “have gotten into a fine mess between ’em” over the publication of The drift, Pickthall, starting in 1905, shrewdly used a New York (and later a London) literary agent to place her poetry and fiction in prestigious American periodicals, among them Century, Harper’s, McClure’s, Scribner’s, and Atlantic Monthly. She did not expect easy rewards from writing poetry. As she wryly noted to friend and fellow poet Helena Coleman on 7 Dec. 1908: “Being a poet in the present state of the market is like saying ‘How is your hare-lip today?’” Though most critics have concurred with Archibald McKellar MacMechan* that “her legacy to Canada is a sheaf of true poems,” the ambitious Pickthall wrote more fiction during her very productive decade after 1905. Her poetry might be highly praised, but it paid little, while stories fetched as much as $150.

This sum represented four months’ salary at Victoria University Library, where Pickthall, with the help of Helena Coleman, obtained work in 1910 as a librarian and research assistant. Her mother’s sudden death in February 1910 had devastated her; work, it was believed, would help. In addition, it was necessary for her to earn a steady income. (Marriage never seems to have been a serious consideration.) Back problems and possibly a nervous breakdown in the spring of 1912 obliged her to take a leave of absence.

Later that year, determined to fulfil her dream of travel, Pickthall went to England, where she became part of the lively household of her uncle in Hammersmith (London), Dr Frank Reginald Mallard. With her second cousin Edith Emma Whillier she rented Chalke Cottage near Bowerchalke; she spent her summers there writing, beginning in 1914 with “Poursuite joyeuse,” a historical novel. Published first by Methuen in London in 1915 as Little hearts, it earned no more than £15. Nor, despite favourable reviews, did it facilitate Pickthall’s entry into the London literary world, which she felt was closed to her as a colonial, a situation unaffected by the publication in 1916 of an expanded edition of her poems, The lamp of poor souls. Moreover, she was out of touch with the American market.

Pickthall’s discouragement over her literary career deepened with her horror at the human costs of World War I. She sought to be useful in the war effort by taking training over the winter of 1915–16 in automobile mechanics. When she did not secure a job as an ambulance or truck driver, she enrolled in a gardening course which lengthened into a summer-long position as part-time secretary to the principal and a part-time market gardener. This experience was the basis for an essay, “Women on the land in England,” later published in East and West. Subsequently she joined another woman student known only as Long-John in Hampshire’s New Forest, where she planned to set a novel. Between March and November 1917 the six-foot-tall Long-John joined her in a financially unsuccessful venture to grow vegetables at Chalke Cottage. One can only speculate as to whether this was an emotionally fulfilled time for Pickthall, whose witty letters reveal a primarily woman-identified woman.

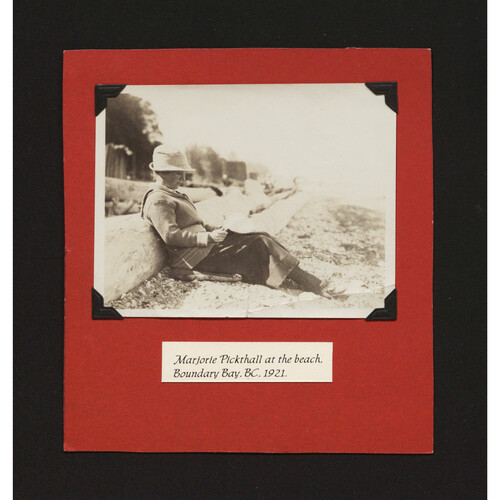

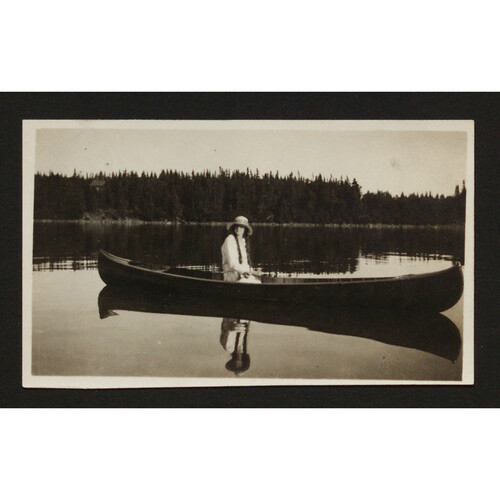

During the winter of 1917–18 Pickthall worked as assistant librarian in the South Kensington Meteorological Office. She was obliged to resign in May 1918 because of eye problems, which the summer at Chalke Cottage did not cure. Nonetheless, she wrote 20 stories between July and December, half of which were sold by January. Another creative burst between September and December 1919 produced a novel (“The bridge: a story of the Great Lakes”), a verse drama (The wood carver’s wife), and 16 stories. “Canada sick,” she set sail from Liverpool on 22 May 1920 on the proceeds of what had been published. With only a week’s stop in Toronto, she travelled with a literary friend, Edith Joan Lyttleton, to British Columbia, where she settled in a cabin at Lang Bay, and then in a shack at the summer camp of Isabel Ecclestone Mackay [MacPherson] on Boundary Bay. Here she revised “The bridge” and researched another novel, “The beaten man,” to be set in the wilderness of British Columbia. Her time with Mackay produced ribald humour as well as literary sparkle. A visit by expatriate novelist Arthur John Arbuthnott Stringer in May 1921 prompted them to attack his recent book, The wine of life. “It seems a pity that Canadian writers should make a name in New York’s larger world by books of that type,” Pickthall wrote Helena Coleman on 12 June. “Isabel Mackay and I are going to do one together which will make The wine of life look like coca-cola. It is going to be called ‘Life’s Envelope.’ N.B. & P.S. This is a nawful double entendre. The cover design will have black crêpe-de-chine undies on it.”

Published in the University Magazine in April 1920, The wood carver’s wife literalizes the metaphor of killing life to produce art. In this tale, which Pickthall felt was her finest work, a Quebec carver murders his wife’s lover in order to have a model for the proper expression of grief for his wooden pietà. Here Pickthall’s use of synaesthesia conveys her vision of the complex web of human and natural realms, in which masculine containment contrasts with feminine intertwining. “The cedar must have known . . . I should love and carve you so,” the sculptor sang to his wife/model. The play was staged at the New Empire Theatre in Montreal in March 1921 and later at Hart House Theatre in Toronto. Audiences responded enthusiastically, as did reviewers, but Pickthall was distressed to learn that the role of the wife had been emphasized over the carver and a native character turned into “a sugary child.” This difference points to a general misinterpretation of her work, highlighted by Mackay’s preface to the book version of 1922, which notes the close relation of the play’s “passions and despairs” to Pickthall’s life. Still, the play received amateur productions as recently as 1957. Frustration with the sentimentalization of her work may be what Pickthall had in mind when she railed to Helena Coleman against the contradictions between a “greed for experience plus a slavery to convention”: “To me the trying part is being a woman at all . . . what the deuce are you to make of that? – as a woman? As a man, you could go ahead and stir things up fine.”

Attention to gender might invite a reading of The bridge as another critique of male-female relationships. Set on the Toronto Islands, it deals with the failure of a self-centred engineer to take responsibility for the death of his brother and for the love of his wife. Atonement comes through memory and selfless devotion. Pickthall’s biographer, Lorne Albert Pierce*, inaptly considers this plot “Balzacian” realism and hails the novel as “a landmark in Canadian fiction” for its “representation of the supreme importance which nature assumes in this country.” However, a manuscript reviewer for Hodder and Stoughton, its Canadian publisher in 1922, noted its violation of “the laws of probability.” This assessment, Pickthall retorted, showed a lack of knowledge of the “psychological conditions” of the characters. Even the most sympathetic reviewer, poet Alfred Gordon of Montreal, noted problems in characterization. Less the desired “great Canadian novel” than a symbolist treatment of ethical choices along the lines of Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim, which Pickthall admired, the novel nonetheless marked a change in her fortunes: the serial rights were sold to Everybody’s Magazine (New York) for $1,000 and to the Sphere (London), and negotiations were initiated on the film rights.

A shift toward greater realism is evident in Pickthall’s notes to “can the fantastic” in “The beaten man.” She struggled over this novel in Victoria in the winter of 1920–21, had Isabel Mackay read extracts, and rejected five drafts. Despite the change in her treatment, it promised to be about yet another lost man, the forces of “time and memory,” and yearning hearts. Taking issue with the observation of British poet Rupert Brooke that there were “no legendary figures to tread our forests,” Pickthall planned to show “the possibility of the birth of Canadian legend, the making of the white man’s myth,” in a plot centring on timber interests and race relations. In the spring of 1921 she travelled by boat up the west coast of Vancouver Island, settling in the remote native community of Clo-oose; in the summer she took a motor trip through the island’s interior. Subsequently a major breakdown led to her confinement in a Victoria nursing home, where she was unable even to attend to business correspondence. After returning to Vancouver in February 1922, she was advised to have surgery for her disc problem, which she underwent successfully on 7 April; she died unexpectedly of an embolism on the 19th. Her death and her funeral at the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Toronto were reported in newspapers across Canada. Pickthall named her father as her executor, but she left her entire estate to her aunt Laura Mallard, in whose home she had written much of her work. She was buried beside her mother in St James’ Cemetery.

Pickthall’s death overshadowed the publication of The bridge and The wood carver’s wife. Obituaries replaced reviews, with the consequence that her reputation has rested almost entirely upon her early poems, which would form the core of collections published in 1925, 1927, and 1957. In December 1922 the Boston Evening Transcript hailed her short stories as the discovery of the year, though generally they were overlooked. Of her more than 200 stories, the 24 published as Angels’ shoes . . . (London, 1923) failed to sell. Her proposed title, “Devices and desires,” might better have attracted readers to these anti-romantic tales. In the best of them, symbolic atmosphere sustains violent incidents involving men in extreme situations.

Most praised for her lyricism, Pickthall has been called “Canada’s sweetest voice” and “a singer of spiritual songs,” and has been compared in “technical perfection” as a lyricist to both Charles George Douglas Roberts* and William Bliss Carman. (Her only explicit pronouncements on poetics had been discussions of prosody in letters to Alfred Gordon, in which she argued against a rigid application of rules of scansion.) Duncan Campbell Scott*, a poet much liked by Pickthall, felt her work was best “overheard,” with the “strain of melody” floating from a private world beyond. To a younger poet, Edwin John Pratt*, her poems were most successful in their avoidance of sentimentality in the exploration of pathos. In 1957, however, editor Frederick William Cogswell noted her “obsession with death” and regretted the limitations of the poetic conventions of her day, which tended to the Celtic twilight rather than the Metaphysicals. Her sure sense of rhythm and apt choice of words create sustained moods in her best poems, even though her incantatory Swinburnesque assonance and alliteration, persistent melancholy, double-barrelled epithets, and imagery of precious jewels are dated.

Though her early death may have silenced her, as Pierce believed, “before she had reached the zenith of her powers,” it facilitated her canonization in Canadian literary history as it was being written in the 1920s. In dispute was her position: a significant contributor to literature in English? a great Canadian poet? or merely, in Pierce’s reassessment of 1943, “first place among the women writers of Canada in her time”? In addition to his biography of 1925, Pierce, her faithful champion, organized an exhibition in 1943, edited a new edition of her poetry, and promoted her placement in school textbooks. “Resurgam,” “Père Lalement,” and “The bridegroom of Cana,” which remained on the Ontario curriculum throughout the 1940s, appealed to the “romantic sensibilities” of the young of that era. The novelist Henry Kreisel, in noting his response to her poems at “an important moment” for him as an immigrant, remembered her as “the first Canadian literary voice I heard.” Her reputation suffered a heavy blow in 1952 when Desmond Pacey qualified the period in which she wrote as “the age of brass” and dismissed her work as having “little direct experience of life.”

These changing evaluations point to how Pickthall has been situated by both the history of Canadian literature and the historical options available to women writers in her time. Desire was her subject, not death. Recent feminist readings emphasize not so much the facility of her use of classical and biblical mythology but her ability to construct the poetic process in female-centred forms, as in her reworking of the Demeter–Persephone story in “The little fauns to Proserpine” and “Persephone returning to Hades.” Feminist criticism has also recognized, in her handling of the theme of imaginative escape from the bondage of the law, an independent, feminine inflection of decadent fin de siècle poetics. These readings show Pickthall’s work to be more complex than her legacy had hitherto suggested. Certainly her work has received the most sustained critical attention of all the writers of her generation.

Marjorie Pickthall’s papers are in the Alice Rothwell coll. and the Lorne and Edith Pierce coll. at QUA. There is also a substantial Pickthall collection, including numerous photographs, in the Victoria Univ. Library, Toronto.

AO, RG 22-305, nos.45548, 98206; RG 80-2-0-410, no.39545; RG 80-5-0-829, no.22353; RG 80-8-0-180, no.22497; RG 80-8-0-387, no.1961. GRO, Reg. of births, Brentford, 14 Sept. 1883. LAC, RG 31, C1, 1901, Toronto, Ward 5, div.26: 3. St James’ Cemetery and Crematorium (Toronto), Burial records, lot 146, sect.i. Boston Evening Transcript, 9 Dec. 1922. Catholic Register (Toronto), 27 April 1922. Globe, 28 April 1922. P. L. Badir, “‘So entirely unexpected’: the modernist dramaturgy of Marjorie Pickthall’s The wood carver’s wife,” Modern Drama (Toronto), 43 (2000): 216–45. Sandra Campbell, “‘A girl in a book’: writing Marjorie Pickthall and Lorne Pierce,” Canadian Poetry (London, Ont.), no.39 (fall 1996): 80–95. F. [W.] Cogswell, “Marjorie Pickthall,” Fiddlehead ([Fredericton]), August 1957: 38–39. W. E. Collin, “Marjorie Pickthall, 1883–1922,” Univ. of Toronto Quarterly, 1 (1931–32): 352–80. Alfred Gordon, “Marjorie Pickthall as artist,” Canadian Bookman (Toronto), 4 (1922): 157–59. Henry Kreisel, “‘Has anyone here heard of Marjorie Pickthall?’ Discovering the Canadian literary landscape,” Canadian Literature (Vancouver), no.100 (spring 1984): 173–80. J. D. Logan, “The genius of Marjorie Pickthall: an analysis of aesthetic paradox,” Canadian Magazine, 59 (May–October 1922): 154–61; a revised version was published as Marjorie Pickthall, her poetic genius and art: an appreciation and an analysis of aesthetic paradox (Halifax, 1922). I. E. Mackay, “Marjorie Pickthall: a memory,” in M. L. C. Pickthall, The wood carver’s wife (Toronto, 1922), 5–7. A. McK. MacMechan, Headwaters of Canadian literature (Toronto, 1924; repr. 1974), 221–29. Desmond Pacey, Creative writing in Canada: a short history of English-Canadian literature ([rev. ed.], Toronto, 1961); “The poems of Marjorie Pickthall,” in his Essays in Canadian criticism, 1938–1968 (Toronto, 1969), 145–50. Lorne Pierce, Marjorie Pickthall; a book of remembrance (Toronto, 1925). E. J. Pratt, “Canadian writers of the past: Marjorie Pickthall,” Canadian Forum (Toronto), 13 (1932–33): 334–35. D. M. A. Relke, “Demeter’s daughter: Marjorie Pickthall and the quest for poetic identity,” Canadian Literature, no.115 (winter 1987): 28–43. B. K. Sandwell, “The complete Pickthall,” Saturday Night, 3 April 1937: 11. Saturday Night, 29 April 1922. D. C. Scott, “Poetry and progress,” Canadian Magazine, 60 (November 1923–April 1924): 187–95. Janice Williamson, “Framed by history: Marjorie Pickthall’s devices and desire,” in A mazing space: writing Canadian women writing, ed. Shirley Neuman and Smaro Kamboureli (Edmonton, 1986), 167–78.

Cite This Article

Barbara Godard, “PICKTHALL, MARJORIE LOWRY CHRISTIE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pickthall_marjorie_lowry_christie_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pickthall_marjorie_lowry_christie_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barbara Godard |

| Title of Article: | PICKTHALL, MARJORIE LOWRY CHRISTIE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |