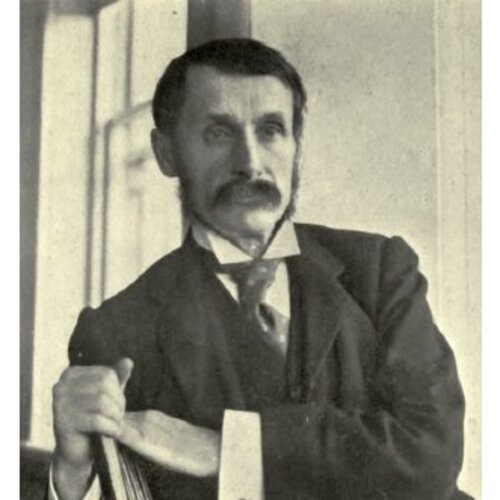

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PARKIN, Sir GEORGE ROBERT, educator, imperialist, and author; b. 8 Feb. 1846 near Salisbury, N.B., youngest of the 13 children of John Parkin and Elizabeth McLean; m. 9 July 1878, in Fredericton, Annie Connell Fisher (1858–1931), granddaughter of Peter Fisher*, and they had six daughters, two of whom died in infancy, and one son; d. 25 June 1922 in London, England.

George R. Parkin’s father was a Yorkshire farmer who had immigrated in 1817; his mother was a Nova Scotian of loyalist descent. In later years Parkin recalled the family’s hard struggle on their farm with “little music, few books, [and] not much polished society.” Yet his mother gave him a love of literature and he attended school whenever time could be “snatched from the hoeing of potatoes, making hay, [or] chopping wood.” These early glimmers of a distant world of learning awakened “a burning desire to know and a longing to see with my own eyes the places one read about – to meet men who wrote books or did things – to get in touch with the world of which the faint echoes only came to one’s country life.” Parkin followed this desire first to the Normal School at Saint John in 1862 and then to positions in primary schools at Buctouche and on Campobello Island. By 1864 he had saved enough to enrol at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, where he imbibed the gospel of mid-Victorian liberalism and progress. He was accepted into Fredericton’s polite society, thereby acquiring the social skills he would need in later life. Upon graduating magna cum laude, he taught at the Bathurst Grammar School (1867–71) before his appointment in 1872 as headmaster of the Fredericton Collegiate School, a position he would retain until 1889.

Parkin formed in these years his lifelong conviction that “the degree of civilization attained by any nation” is a direct result of its standard of education and that the teacher has enormous power by forming “the morals and manners of those . . . whose influence for good or bad will be extensively felt.” This belief would underpin his later career, not only his work in education but also his public campaigns for imperial unity, social regeneration, and Christian responsibility. During this period as well he perfected his public-speaking techniques in a series of local lectures on history, education, democracy, temperance, and imperial unity. Yet these were also troubled years for Parkin. His careful reading of Thomas Carlyle challenged the liberal notions of his university days and his close friendship with John Medley*, the high-church Anglican bishop of Fredericton, undermined the individualistic, evangelical, Baptist faith of his youth and promoted a more learned, liturgical, and holistic approach to religion. Not knowing which way to turn to reconcile his liberalism and conservatism, or his evangelicalism and Anglicanism, he experienced a nervous breakdown. Medley stepped in and sponsored Parkin for a year at the University of Oxford in 1873–74.

This year set the direction for Parkin’s life. As an older student with considerable experience in public speaking, he was a great success at the renowned Oxford Union Society, and he was accorded the unusual honour for a non-degree freshman of being elected its secretary. In a famous debate he defeated the future British prime minister Herbert Henry Asquith, of Balliol College, on the issue of the desirability of imperial unity, Parkin arguing for the affirmative despite the widespread Little Englandism of the time. The attention he received fixed his earlier belief in a united British empire as a force for good in the world. During his Oxford year he also was deeply impressed by Edward Thring, the reforming headmaster of Uppingham School, and saw in Thring’s ideals a necessary corrective to the lower standards of pioneer schools in Canada. Thring was equally charmed and, after many years of friendship, assigned Parkin the task of writing his biography. Through Thring, as well as through personal contacts with the brilliant circle at Balliol and through John Ruskin, Parkin was attracted to the idealism that animated much late-19th-century British and Canadian life. Like many of his contemporaries, he accepted idealism as a practical creed rather than a philosophical system, a belief that a moral community in the world would result from the ethical character of citizens moved by a sense of public service rather than by a desire for material gain or individual glory. The creed attracted both liberals and conservatives. Thus in idealism Parkin found a resolution of his earlier struggles. His evangelical energy would now be rechannelled into a lifelong mission to promote the central tenets of Christian idealism in empire, school, church, and society.

Parkin spent the next 15 years teaching in Fredericton. He tried in his own school and in a connected residence he founded to implement Thring’s concept of building citizenship through the regimen of residential life and classical education under a committed headmaster. These initial residential experiments were not successful: there were few paying students and the cost of supplies was high. While disappointed, Parkin remained a master teacher. His imaginative classroom methods have been credited with nurturing in these years the Fredericton school of poets led by William Bliss Carman and Charles George Douglas Roberts*. In a more opportune setting as headmaster of Toronto’s Upper Canada College from 1895 to 1902, Parkin took a moribund institution and, explicitly following Thring’s methods, succeeded in making it the premier private school in Canada. He ably raised money, added buildings, hired better masters, and reformed the curriculum, but his core aim was the production of Christian gentlemen. He poured his energy into the headmaster’s Sunday evening addresses to the boys and remained convinced that “nothing stamps a school as really great save the power of turning out men of high and noble character.”

Parkin’s main avenue for the realization of Christian idealism was not the school, however, but the British empire. Throughout his life, but especially during the years 1889-95, he was the leading spokesperson for imperial unity. His campaigns through thousands of speeches and interviews, scores of articles, and several books were very wide-ranging. In the employ of the Imperial Federation League, founded in London in 1884, he left Fredericton to stump across New Zealand and Australia throughout 1889. Bolstered by the reputation he gained there, he settled with his family in England to undertake five years of freelance lecturing and writing for the imperial cause all across Britain, his activities sometimes sponsored by the League, often based on his own personal contacts. His principal manifesto appeared in 1892 as Imperial federation, the problem of national unity. That year as well he brought out a school textbook, Round the empire, which would sell 200,000 copies and go through four editions by 1919. He also published, in 1893, a large wall map for schools that illustrated the unity of Britain’s oceanic empire. He had visited Canada in 1892 to lecture extensively there, and began then his long affiliation with the London Times, writing a series of reports on Canadian history and geography (published together as The great dominion in 1895).

These were difficult campaigns for Parkin – quite aside from the inadequate financial base on which he operated. Though imperial federation had significant support in Canada, from such advocates as George Taylor Denison and George Monro Grant*, many imperialists there were wary of being too closely tied to, or taxed for, a formally federated British empire, where Britain by force of numbers would dominate. Many British imperialists, on the other hand, felt that the colonies were not paying their fair share of imperial defence and other burdens, and they wanted closer ties and more tax revenues. Parkin tried to bridge these two positions, but controversy arose. There were celebrated disputes with the veteran Canadian politician and high commissioner in Britain, Sir Charles Tupper*, which forced the dissolution of the Imperial Federation League in 1893, and a series of extended attacks on Goldwin Smith*’s anti-imperialism and North American continentalism.

Despite the spiritual motivation of Parkin’s imperialism, he did not ignore the practical arguments favouring unity. Influenced by the writings of historian John Robert Seeley and naval theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan, Parkin stressed to the British that, with their oceanic empire, their world position rested on sea power. Given the realities of distance and the dependence of steamships on coal supplies and coaling bases guarded by fortified naval stations, the empire needed to retain, for commerce or defence, the quadrilateral of Australasia, South Africa, Canada, and the United Kingdom, and all the connecting islands and waterways. Without this geopolitical configuration, he presciently forecast, Britain would sink within 50 years into the ranks of the second-class powers before the rising land-based empires of Russia and the United States. To Canadians and Australians, Parkin pointed out that, without the empire, the individual dominions would be battered on the world stage by aggressive superpowers. Self-interest, then, required unity – and the communications revolution of fast steamships, the telegraph, underseas cables, and connecting railways and canals across an “all-red route” ably defended, combined with a common language, literature, and culture, made unity possible.

Parkin never lost his Canadian orientation, and he naturally articulated at some length Canada’s position in a united empire. He sought to enhance his native country’s imperial place, especially in the face of an aggressive United States, then perceived to wish for hemispheric economic leadership at least, and perhaps political integration as well. For Parkin, imperial unity did not mean subsuming Canada’s interests under those of the British colonial administration; rather it would provide a chance for Canada’s fledgling national ambitions to have reasonable scope internationally. Indeed, as the senior dominion, as the geopolitical linchpin in the all-red route, as a nation built on loyalty to the empire, with vast open spaces for immigrants, bountiful natural resources, and a wellspring of racial vigour engendered by a northern climate, Canada was positioned to be the “keystone” of empire. He urged the country to accept its destiny and transform itself from weak colony into strong imperial partner. In Canada he promoted the imperial projects of Sir Sandford Fleming* and others, effectively lobbying for such practical measures to unite the empire as all-red-route telegraph cables, imperial penny postage, productive colonial conferences, and imperial trade preferences. He was especially vocal in pressing in 1899–1902 for the formation of Canadian contingents to fight in the South African War.

The pan-Britannic union that Parkin advocated was not an end in itself, or a means for jingoism, militarism, or financial gain. He viewed it rather as a vehicle for the realization of idealist principles. With imperial power came moral responsibility. In an entirely characteristic speech he noted in 1894 that the Anglo-Saxon race “has temptations of an exceptional kind to yield itself to mere materialism, to forget that the things of the spirit are what endure and conquer in the end.” Anglo-Saxons must not “lose the great moral purposes of life in the race for gain.” Rather they must view the empire as a means of spiritual regeneration: “The more clearly we realize the growing power, the ever widening influence, the increasing prestige of the empire, the more surely will the thought turn us to self-examination and self-improvement.” A strong, united empire would be a stimulant to moral reform of the rulers in Britain and the dominions, then threatened by growing materialism and social declension, and equally to the improvement of subject peoples abroad. In a telling phrase, he saw himself as “a wandering Evangelist of Empire.”

Parkin’s imperial campaigns eventually won his family moderate prosperity and social respectability. He himself became the confidant of prominent figures both in his native land and abroad. In Canada he had the ear of governors general Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon], Lord Minto [Elliot*], and Lord Grey*; he played a role in the policy decisions of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, and was an adviser as well to other cabinet ministers and to leading journalists. In England he personally influenced the imperial ideas of Asquith, Lord Rosebery, Lord Milner, Winston Churchill, and Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery, and moved tens of thousands of others to cheering support. His name was coupled by contemporaries with those of Seeley, Rudyard Kipling, and Cecil John Rhodes as the leading advocates of the “new imperialism,” and many commentators assigned to him the key role in swaying public opinion to the imperial cause.

Because of his long educational and imperial experience, Parkin was invited by the Rhodes Trust in 1902 to be the first organizing secretary of its scholarship program. Travelling all over the empire and the United States several times before his retirement in 1920, he established the Rhodes scholarships on a permanent and prestigious basis. His English home at Goring became a meeting place for current and former scholars as well as for a host of empire-wide visitors. From this position he continued his speaking and writing on imperial matters, publishing biographies of Sir John A. Macdonald* (1908) and, within a larger account of the scholarships, of Rhodes (1912), both of which not surprisingly emphasized their subjects’ imperial virtues. He campaigned vigorously during World War I to keep idealism’s lessons front and centre and to build on the imperial unity being demonstrated by the dominions on the battlefields. In 1917–18 the British government asked him to use his contacts from the Rhodes scholarships to lecture all over the United States and attempt to counter anti-British or neutralist sentiment there. After the war he accepted the new definitions of dominion autonomy which evolved from the Paris Peace Conference, for his imperialism had always focused on the moral and spiritual unity of empire, displayed so clearly in the war, rather than on any particular constitutional formula. At the end of his life he devoted more time to the reform of the Church of England, in which he was a prominent lay leader. Many honours came his way: honorary doctorates from several universities, including his beloved Oxford, a cmg in 1898, and a kcmg in 1920.

Parkin’s life was significant on several levels. His educational accomplishments, especially at Upper Canada College and with the Rhodes scholarships, have lasted a century. His many imperial campaigns and writings in the pre-1914 period were an important stimulus to the popularity of the new imperialism, which had vast consequences. His view of British imperialism and Canadian nationalism as complementary forces was influential, and his Christian idealism was illustrative of a powerful motivating force for many social and spiritual reforms in the pre-war years. Yet his empire was really a white empire of the mother country and the old dominions and, even within them, of the Anglo-Saxon race. French Canadians, Afrikaners, and the growing number of European immigrants in the dominions, let alone the non-white majorities in the newer colonies of Asia and Africa, could never accept Parkin’s racial and cultural formulations. Critics further argued that the empire was a rather incongruous means, with its entrepreneurs and jingoists, to achieve Christian idealist ends. Idealism itself did not long survive the upheavals of the early 20th century.

Although the specific programs Parkin supported have long vanished, the Canadian conservative tradition of which he is part proved more durable. Conservatives of this approach – respectful of history, valuing unity under the crown and service to nation before self, promoting British and Commonwealth ties, wary of American economic integration and popular culture, and shunning materialism and individualism for a sense of community and tradition – have included Parkin’s sons-in-law Charles Vincent Massey* and William Lawson Grant*, and his grandson George Parkin Grant*. The latter’s Lament for a nation: the defeat of Canadian nationalism (Toronto, 1965) explicitly bemoans the passing of his grandfather’s vision in the face of American dominance in Canadian culture. Vestiges of Grant’s lament (and thus of Parkin’s ideal) are still heard in the rhetoric of the federal Conservative and New Democratic parties.

[Sir George Robert Parkin’s publications include Imperial federation, the problem of national unity (London and New York, 1892); Round the empire; for the use of schools (London, 1892); The great dominion: studies of Canada (London and New York, 1895); Edward Thring, headmaster of Uppingham School: life, diary and letters (2v., London and New York, 1898); Sir John A. Macdonald (Toronto, 1908); and The Rhodes scholarships (Toronto, 1912). A comprehensive bibliography of his works and of the archival sources relevant to his life appears in the author’s doctoral dissertation, “‘Apostle of empire’: Sir George Parkin and imperial federation” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1977). A selection of the major manuscript collections is listed below. t.c.]

Bodleian Library, Univ. of Oxford, Eng., Viscount Alfred Milner papers (mfm. at LAC, MG 27, II, A3). Durham Univ. Library, Arch. and Special Coll. (Durham, Eng.), GB-0033-GRE (Earl Grey papers), sect.4. LAC, MG 27, II, B1; MG 29, B1; D46; E29; MG 30, D44; D59; D77; MG 32, A1. QUA, Lorne and Edith Pierce coll., Bliss Carman papers. Rhodes House Library, Univ. of Oxford, Rhodes Scholarship Trust, corr. (mfm. at LAC, MG 28, I, 58). Upper Canada College (Toronto), Board of governors and board of trustees, minutes. Carl Berger, The sense of power; studies in the ideas of Canadian imperialism, 1867–1914 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). D. L. Cole, “Canada’s ‘nationalistic’ imperialists,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 5 (1970), no.3: 44–49. Terry Cook, “George R. Parkin and the concept of Britannic Idealism,” Journal of Canadian Studies, 10 (1975), no.3: 15–31; “A reconstruction of the world: George R. Parkin’s British empire map of 1893,” Cartographica (Toronto), 21 (1984), no.4: 53–65. DNB. R. B. Howard, Upper Canada College, 1829–1979: Colborne’s legacy (Toronto, 1979). John Willison, Sir George Parkin: a biography (London, 1929).

Cite This Article

Terry Cook, “PARKIN, Sir GEORGE ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/parkin_george_robert_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/parkin_george_robert_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Terry Cook |

| Title of Article: | PARKIN, Sir GEORGE ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |