Source: Link

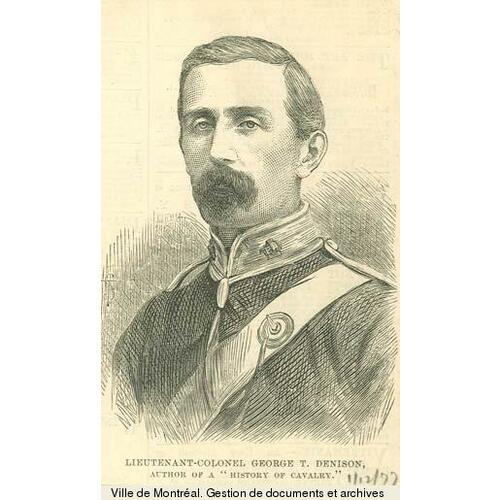

DENISON, GEORGE TAYLOR, lawyer, militia officer, author, politician, police magistrate, and imperialist; b. 31 Aug. 1839 in Toronto, eldest child of George Taylor Denison* and Mary Anne Dewson; m. first 20 Jan. 1863 Caroline Macklem (d. 1885) in Chippawa, Upper Canada, and they had three sons and three daughters; m. secondly 1 Dec. 1887 Helen Amanda Mair in Perth, Ont., and they had two daughters; d. 6 June 1925 in Toronto.

Known by contemporaries as the “watchdog” of the British empire, George Taylor Denison inherited a family legacy of antipathy to the United States, loyalty to the crown, conservative political values, and military service. His great-grandfather, a brewer and farmer from Yorkshire, was induced to immigrate to Upper Canada in 1792 by the province’s receiver and auditor general, Peter Russell*. For managing Russell’s estate at York (Toronto), he received a 1,000-acre grant. His grandfather George Taylor Denison I, who married the daughter of a prominent landowner and United Empire Loyalist, added to the family tradition of imperial service by enlisting with the 3rd York Militia during the War of 1812. The tradition continued with his father, George Taylor Denison II, who served during the rebellion of 1837–38, played an important role in the reorganization of the Canadian militia in 1855, and commanded the 1st Volunteer Militia Troop of Cavalry of York County (designated the Governor General’s Body Guard in 1866). As well, he was an alderman for St Patrick’s Ward in Toronto. The burden of tradition and expectation thus weighed heavily upon George Taylor Denison III.

As befitted his family’s social status, Denison was educated at Upper Canada College, where his performance was unspectacular. Expelled from Trinity College by provost George Whitaker* for insubordinate behaviour, he transferred to the University of Toronto and earned a degree in law. Called to the bar in 1861, he would later go into practice with his brother Frederick Charles*. The law, however, held no interest for him. His heart was with the militia. Gazetted cornet in his father’s troop in the fall of 1854, he rapidly rose through the ranks, from captain in 1857 to lieutenant-colonel and commander in 1866.

Denison’s passion for military matters and gift for polemics first became evident in 1861 when, in the wake of the Trent affair [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*], he anonymously published Canada, is she prepared for war? (Toronto). This pamphlet, which urged British North Americans to uphold their forefathers’ martial valour and to ready themselves against a possible attack from the United States, ignited a lively newspaper debate and soon resulted in another tract, The national defences . . . (Toronto, 1861), in which Denison argued for a properly trained and equipped mounted infantry. In A review of the militia policy of the present administration (Hamilton, 1863) he responded (under the pseudonym Junius) to the defeat of John A. Macdonald*’s Militia Bill of 1862 with a scathing attack on the government’s neglect and ignorance of military matters.

Denison aspired to a career as a professional soldier, but his sympathy for the South during the American Civil War ultimately cost him his ambition. His identification with the South came naturally: it represented an idyllic society that embodied the social order, conservative values, and chivalric traditions he wished to see maintained in British North America. He drew parallels between his loyalist ancestors, who had fought to uphold their principles against the demagoguery of American patriots, and the southerners, who were struggling to preserve their identity and way of life. Fearing the consequences of a northern victory for the future of British North America, Denison actively backed the Confederate cause despite Britain’s official neutrality. In September 1864 he received a visit from his uncle George Dewson of Florida, who had been commissioned to assess support for the Confederacy in British North America. Denison’s farm home, Heydon Villa, on his father’s estate in west Toronto, became a haven for Confederate agents, exiles, and sympathizers and a clearing house for smuggled documents. He also became involved in efforts to purchase the steamer Georgian, which was to be used as a raider on the Great Lakes. The diplomatic crisis and lawsuits that followed the discovery of this plan effectively ended his prospects for a full-time military career, a disappointment that repeated promises from politicians and his own tireless efforts could not reverse. A frustrated Denison entered local politics and served as a councilman for St Patrick’s Ward from 1865 to 1867. He commanded the Governor General’s Body Guard during the Fenian raids of 1866 and wrote Modern cavalry: its organisation, armament, and employment in war . . . (London, 1868), an impassioned case for mounted infantry based on his own experience and close study of the Civil War. He suffered another blow to his ego when British critics dismissed the book as the work of a mere colonial.

Appalled by the lack of national spirit following confederation, disillusioned by the state of Canadian politics, and fearful of the United States, Denison joined with Charles Mair, William Alexander Foster*, and others to found the Canada First movement in 1868. Inspired by Thomas D’Arcy McGee*’s vision of a northern nation, Canada First celebrated the new dominion’s rugged landscape and climate and its Anglo-Saxon/Protestant heritage. This small social group was hurled into national prominence by the Red River uprising of 1869–70. Seeing the actions of Louis Riel* and his followers as an affront to Canada’s territorial ambition, the group launched a vigorous assault upon the “traitors.” Denison led the charge, writing bellicose letters to the newspapers, organizing demonstrations, and appealing to all loyal English-speaking Canadians to defend their birthright. Special venom was reserved for Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, the militia minister who had blocked Denison’s advancement to the post of adjutant general of cavalry and who, in Denison’s eyes, represented French Canadian opposition to the force sent to Red River.

The success of these tactics had a lasting effect on Denison. The same belligerent rhetoric and fearmongering would characterize his later campaigns against closer economic relations with the United States and on behalf of imperial unity. His immediate priority, however, was ensuring the Anglo-Saxon character of the northwest. He and his Canada First associates created the North West Emigration Aid Society in 1870 to assist in the recruitment of desirable settlers. Denison outlined his national vision in an address he first delivered in Weston (Toronto) in early 1871, “The duty of Canadians to Canada,” in which he attacked British indifference and warned of the dominion’s vulnerability. Canada’s destiny, he insisted, depended on the cultivation of pride and patriotism, the development of its resources, and the creation of politics freed of faction and dedicated to the national good. Such a course would allow Canada to assume its rightful place as a full partner in the empire. Disillusioned with the governing Conservative party, he sought election to the House of Commons for Algoma as a Liberal in 1872. Defeated by John Beverley Robinson*, he was rewarded for his efforts by friends in the provincial Liberal government of Oliver Mowat* and made Ontario’s emigration commissioner in London. His exposure there to reviving imperialist feeling reinforced his Canada First sentiments. The position was temporary, however, and he returned to Canada in early 1874, with no immediate prospects before him.

As Denison approached middle age, he was haunted by his lack of personal accomplishment. “If a man does not make his mark in the world or be in a fair way of doing it before he is forty he will never do anything afterwards,” his father had once warned him. When he learned of the substantial cash prizes offered by the Russian government for the best history of cavalry, he decided to return to his first love, the military, and resolved to make his reputation as a military historian. He threw himself into the work, rising early to read and write, acquiring a large library on military history at great expense, and travelling to London and St Petersburg to do research. Denison completed his magnum opus in December 1876 and presented the manuscript to the prize committee in person, but it refused to consider his work on the grounds that the translation, done by a Russian woman in New York, was sub-standard. Only after the book appeared in English was he awarded the 5,000-rouble first prize. Although A history of cavalry from the earliest times, with lessons for the future (London, 1877) received mixed reviews at the time, it has since been hailed as the definitive work in the field.

On his return to Canada in 1877, Denison assumed the post of police magistrate for the City of Toronto, a position he would retain until the summer of 1921. He owed the appointment to Oliver Mowat. Denison’s contemporary seat on the Board of Police Commissioners was not seen as a conflict of interest. He ran his court like a well-oiled machine. Much to the annoyance of the city officials who paid his salary, he routinely cleared his docket in a couple of hours before lunch. Usually faced with an enormous caseload, and with little interest in the causes or prevention of crime, he had no use for legal technicalities or procedural niceties. His was “a court of justice, not a court of law,” he proudly asserted. By his own admission, he relied more on intuition than on evidence. Although he liked to boast that he judged impartially, some groups fared better than others: retired soldiers and members of Toronto’s respectable classes could expect leniency but striking workers, parvenus, Irishmen, and blacks invariably received harsh treatment. Denison nonetheless took a paternal interest in the unfortunate members of the lower classes who filed through his court. He championed legal aid, chastised the legal profession for profiting from people’s misfortunes and prolonging cases, and denounced moral reform groups that tried to impose their standards upon criminal elements “who offended their tender susceptibilities.” His unorthodox methods were notorious – his court even became something of a tourist attraction. By the time of his retirement, there were calls for a full overhaul of the then outmoded Police Court, which consisted of four magistrates, including Rupert Etherege Kingsford*, women’s and children’s divisions, and seven clerks.

Denison’s swift administration of justice freed him to pursue other interests. An Anglican of evangelical inclination, he helped found and served on the first board of management of the Protestant Episcopal Divinity School [see James Paterson Sheraton*]. He became one of the principal forces behind the revival of the loyalist tradition, as an organizer of the loyalist centennial celebrations in 1884 and a founding member in 1896 of the United Empire Loyalist Association of Ontario. He broadcast the tradition long and often. In his presidential address to the Royal Society of Canada in 1904, for instance, he spoke on the loyalist influence in Canadian history. He found in the tradition not only the reflected glory of his ancestors’ accomplishments but also a usable past, which could be called upon to justify closer ties to Britain and the empire and to attack opponents who advocated greater independence or closer economic and political relations with the United States. As constructed by Denison and others, the tradition served too to defend a social order threatened by industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. Denison’s rabid anti-Americanism, in fact, owed much to his fear that the social ailments afflicting the United States would soon infect Canada.

Denison’s patriotism had been tested in the spring of 1885, when he and the Governor General’s Body Guard saw service during the North-West rebellion. Because of his lingering hostility to the federal government, he had little enthusiasm for the conflict and had initially refused to volunteer his troop. He objected, he told Charles Mair in March, to the use of the militia “to defend a Government of land sharks who have villainously wronged the poor native and the actual settler.” Moreover, he had been deeply shaken by the death of his wife on 26 February. His fighting spirit returned with the formation in May of the Canadian branch of the Imperial Federation League; he was named chair of the branch’s organizing committee, and would later be vice-president and president. Although Denison and the league succeeded in whipping up nationalistic fervour, especially after the appearance in 1887 of the movement for commercial union with the United States [see Erastus Wiman*], they failed to convince the league’s British members of the virtue of imperial trade preferences. When internal divisions caused the league to collapse, Denison played an important role in 1895 in creating a new organization, the British Empire League, and he would serve as president of its Canadian branch for many years. Although military considerations dominated Denison’s imperial outlook, he frequently used the rhetoric of religious crusade in his speeches and writings, and his evangelical Anglicanism certainly helped shape his view of events. In this religious sense, his imperialism was comparable to that of George Monro Grant* and George Robert Parkin.

Colonel Denison remained in the vanguard of the imperialist cause throughout the remainder of his life. He championed Canadian participation in the South African War and contributions to the Royal Navy, he surpassed most imperialists by campaigning in 1902 for an imperial defence fund derived from duties on foreign imports into Britain and the colonies, and he vigorously opposed the efforts of Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s government to negotiate reciprocity with the United States in 1911. A frequent speaker and newspaper commentator, he brought to the cause an unrelenting drive and a steely resistance to criticism. Passed over several times for imperial honours, he eventually claimed he had not wanted any. “His self-laudation has long been a standing joke in Canada,” Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*] confided to Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain in 1900. As well, some British career soldiers regarded his Body Guard as a showy, lightweight outfit, top-heavy with officers and ncos. Unswayed, he chronicled his efforts on behalf of the empire, and his arguments for federation and against free trade, in The struggle for imperial unity . . . (Toronto, 1909). With the approach of war in Europe, he found a new demon, Germany. Although his combination of anti-Americanism, imperialism, and nationalism lost much of its force in the years following World War I, Denison remained unmoved in his convictions.

Despite his celebrity, relatively little is known about his private and family life. He kept a daily diary from 1864 until his death, but rarely recorded his deepest personal thoughts. In 1863 he had married the niece of the Reverend Thomas Brock Fuller*; in 1887 he married Charles Mair’s 22-year-old niece. He appears to have been a demanding but loving father who impressed on his sons the same spirit of loyalty, duty, and family pride that had been implanted in him during his own childhood. Extremely class-conscious, he raised his daughters to assume their rightful place at the top of respectable society.

His stern and headstrong manner notwithstanding, Denison had a great sense of humour and relished the caricatures drawn of him in the press. He was almost always portrayed in military uniform striking the pose of the stereotypical British officer and gentleman. He loved to entertain and Heydon Villa, which he rebuilt in 1880, became a regular stop for notables visiting Toronto. A man of boundless energy and ambition, he kept up an exhaustive correspondence with the public men of his day. He thoroughly enjoyed the cut and thrust of vigorous debate but his absolute faith in the correctness of his beliefs cost him several friendships, including that of Goldwin Smith*, whom he almost single-handedly had ostracized from polite Toronto society. By 1922 Denison’s health was failing and he died at Heydon Villa in 1925 at the age of 85.

George Taylor Denison had been raised to be a public man. Although few could match his contribution to the discussions of the great political issues of the day, his life was full of disappointments. Unable to achieve a military career or high elected office, he settled into a series of patronage appointments and crusades. His impact on Canadian opinion lay as much in the opposition he provoked as in the causes he advocated. In many respects, his life reflects the ideas and standards, the frustrations and anxieties, of a class and a generation whose values were fading before the forces that were transforming Canada into a North American nation.

George Taylor Denison’s 1861 pamphlet Canada, is she prepared for war? or, a few remarks on the state of her defences was issued anonymously “by a native Canadian.” In addition to the works mentioned in the text, his publications include The petition of George Taylor Denison, Jr.: to the Honorable the House of Assembly, praying redress in the matter of the seizure of the steamer “Georgian” . . . (Toronto, 1865); History of the Fenian raid on Fort Erie; with an account of the battle of Ridgeway (Toronto, 1866); “A visit to General Robert E. Lee,” Canadian Monthly (Toronto), 1 (January–June 1872): 231–37; Reminiscences of the Red River rebellion of 1869 ([Toronto?], 1873); Canada and her relations to the empire (Toronto, 1895); “Sir John Schultz and the ‘Canada First’ party,” Canadian Magazine, 8 (November 1896–April 1897): 16–23; The British Empire League in Canada . . . (Toronto, 1899); Soldiering in Canada: recollections and experiences (Toronto, 1900); “Canada and the Imperial Conference,” Nineteenth Century and After (London), 51 (January–June 1902): 900–7; “The United Empire Loyalists and their influence upon the history of the continent,” RSC, Trans., 2nd ser., 10 (1905), proc.: xxv–xxxix; and Recollections of a police magistrate (Toronto, 1920).

AO, F 10009; F 1076-A-11; RG 80-8-0-151, no.6419. LAC, MG 29, D61; E29. QUA, Charles Mair fonds. TRL, SC, Denison family papers. United Empire Loyalists’ Assoc. of Canada, Toronto Branch Arch., Corr.; Minutes. Leader (Toronto), 23 Jan. 1863. Carl Berger, The sense of power; studies in the ideas of Canadian imperialism, 1867–1914 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). Canada Law Journal (Toronto), 36 (1900): 517–20. Canadian annual rev., 1902–17. Canadian Journal of Commerce (Montreal), September 1890: 570. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). The centennial of the settlement of Upper Canada by the United Empire Loyalists, 1784–1884 . . . (Toronto, 1885). E. M. Chadwick, Ontarian families: genealogies of United-Empire-Loyalist and other pioneer families of Upper Canada (2v., Toronto, 1894–98; repr., 2v. in 1, Lambertville, N.J., [1970]; repr., vol.1, intro. W. F. E. Morley, Belleville, Ont., 1972). J. F. Fraser, Canada as it is (London, 1905). D. [P.] Gagan, The Denison family of Toronto, 1792–1925 (Toronto, 1973). G. H. Homel, “Denison’s law: criminal justice and the Police Court in Toronto, 1877–1921,” OH, 73 (1981): 171–86. Norman Knowles, Inventing the loyalists: the Ontario loyalist tradition and the creation of usable pasts (Toronto, 1997). Lord Minto’s Canadian papers: a selection of the public and private papers of the fourth Earl of Minto, 1898–1904, ed. and intro. Paul Stevens and J. T. Saywell (2v., Toronto, 1981–83). Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, 1970). Trinity College conducted as a mere boys’ school, not as a college (Toronto, 1858). H. M. Wodson, The whirlpool: scenes from Toronto Police Court (Toronto, 1917).

Cite This Article

Norman Knowles, “DENISON, GEORGE TAYLOR (1839-1925),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/denison_george_taylor_1839_1925_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/denison_george_taylor_1839_1925_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Norman Knowles |

| Title of Article: | DENISON, GEORGE TAYLOR (1839-1925) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |