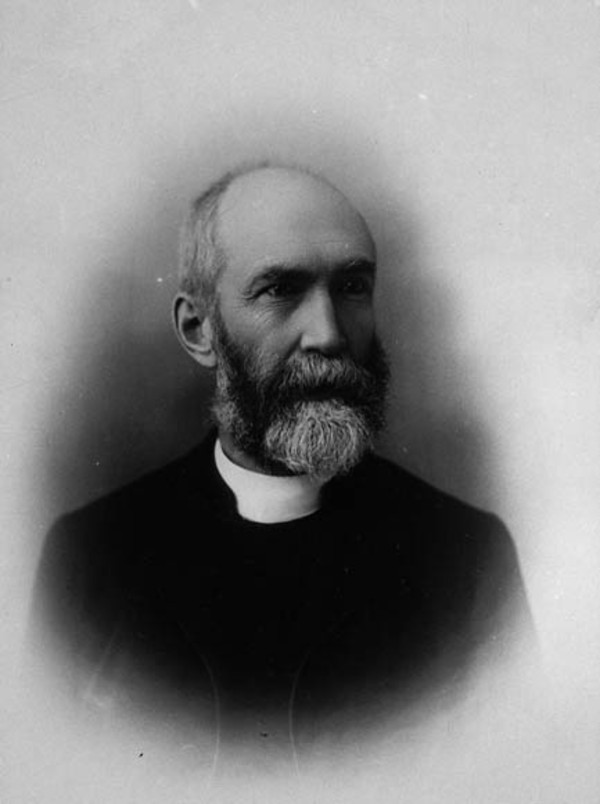

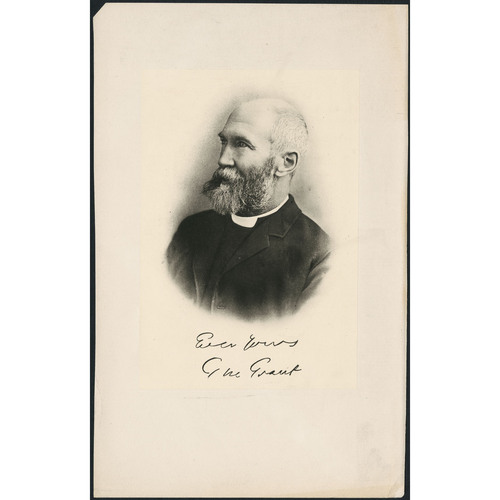

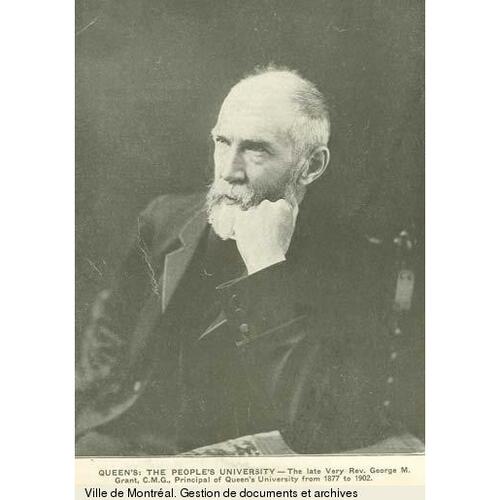

GRANT, GEORGE MONRO, Presbyterian minister, author, and educator; b. 22 Dec. 1835 in Albion Mines (Stellarton), Pictou County, N.S., third child of James Grant and Mary Monro; m. 7 May 1867 Jessie Lawson in Halifax, and they had two sons, William Lawson* and George; d. 10 May 1902 in Kingston, Ont.

George Monro Grant’s father, though a man of diverse talents and an amiable disposition, was unable to support adequately a wife and five children. After trying farming, schoolteaching, and legal work, he turned to more speculative ventures which resulted in financial disaster. It was Mary Grant’s combination of intense piety, ambition, and common sense that constituted the dominant influence on the children and led to George’s receiving an excellent education. His great natural energy was directed towards the ministry both by his mother’s hopes and by the accidental loss of his right hand at the age of eight, which precluded manual labour.

Pictou County, when George was growing up, reflected in microcosm a combination of the cultural, religious, and political tensions which prevailed in Scotland. Most of the settlers, like the Grants, were Gaelic-speaking Highlanders with strong loyalties to the established Church of Scotland; however, their first ministers, including James Drummond MacGregor* and Thomas McCulloch*, were evangelical Dissenters, representatives of the Lowland, English-speaking anti-burgher tradition and members of the Presbyterian Church of Nova Scotia. The linguistic, ecclesiastical, and cultural differences between Highland and Lowland coincided, moreover, with the political distinction between tory and liberal.

After attending McCulloch’s Pictou Academy, Grant was enrolled from 1851 to 1853 in the anti-burgher seminary at West River (Durham), which was under the direction of James Ross* and John Keir*. Ross provided Grant with the solid grounding in Scottish common-sense philosophy that was to remain an abiding feature of his mind and also exposed him to a particularly uncompromising version of the Calvinism in the Westminster Confession. Through his family and his schooling Grant straddled the great political and ecclesiastical divide in Pictou County, which was of crucial importance to his subsequent career. His years at the seminary exposed him to evangelical influences and resulted in friendships that would allow him to mediate between the various strands of Presbyterianism. They also contributed to a sense of balance which was one of the most striking features of his intellectual make-up. He habitually sought for truth in the common ground that lay between extreme positions.

Grant’s family attended an anti-burgher church until 1853 when they switched to the Kirk church where Allan Pollok was minister. Within months Grant was one of four beneficiaries of that church’s “Young Men’s Scheme” and was sent to Scotland to study for the ministry; he was the only one of the students who could not defray any of the costs. He attended the University of Glasgow from 1853 to 1860 and performed brilliantly. He won prizes in subjects as diverse as Greek and chemistry, and was awarded his ma in 1857 with great distinction. He also displayed his gift for exuberant and charismatic leadership, whether in debate or as captain of the football team. More important than his formal studies, however, was the personal influence of Norman Macleod, then the leading figure in the Church of Scotland and, for Grant, “the grandest man I ever knew.” Grant attended the Barony Church, where Macleod was the minister, styled his own preaching on Macleod’s, and shared many of his mentor’s opinions, including the desirability, at least theoretically, of an established church, a passion for missions, and an interest in comparative religion.

Macleod and a cousin, John McLeod Campbell, were at the head of a movement within the Church of Scotland away from the Calvinism of the Westminster Confession, with its notions of double predestination and of an Atonement limited in its effect to the elect, in favour of a broader evangelicalism, less insistent on the “total depravity” of human nature and more optimistic about an underlying harmony between reason and revelation. Macleod, and the London periodical he edited, Good Words, exposed Grant as well to such broad-church writers as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Thomas Arnold, Julius Charles Hare, Charles Kingsley, and Arthur Penrhyn Stanley. From these theological influences and from the writings of Thomas Carlyle, whose biography of Oliver Cromwell he particularly admired, Grant derived a romantic critique of the “external” emphasis of a Calvinist tradition gone to seed. He believed that the real living faith of the Puritans had largely given way to the empty and desiccated theological cant so effectively satirized in the poems of Robert Burns. Carlyle favoured a return to the “inwardness” of Martin Luther’s faith within the framework of an inclusive national church, and Grant retained a lifelong enthusiasm for the German hero of Protestantism.

Carlyle was also the dominant literary influence on Grant. In addition to Carlyle’s rhetorical style, Grant absorbed from him a deep conviction that history recorded the inexorable verdict of moral law. At the same time that Grant was president of the university’s Conservative Club, he shared with Carlyle a deep-rooted sympathy with the poor. He was scandalized by the slums of Glasgow, where he worked in a mission, and in Carlyle’s writings he discovered the language of prophetic protest which refused to acknowledge the social consequences of industrialism as inevitable. His own flair for writing manifested itself in the commentaries on Scottish affairs he contributed to the Monthly Record of the Church of Scotland in Nova Scotia (Halifax). The 20-guinea prize he won for an essay on “The relations of critical, systematic and historical theology” financed in 1860 a European tour, the highlight of which was to stand in Luther’s footsteps in the cathedral at Worms (Germany).

Grant returned to Nova Scotia in the spring of 1861 with the theological views he was to hold for the rest of his life. His first assignment, as a missionary of the synod of the Church of Scotland, was to organize families into congregations and erect churches at River John in Nova Scotia, and then at Georgetown, St Peters Road, and Brackley Point on Prince Edward Island. He was so successful that in 1863 he was called to St Matthew’s Church in Halifax, the largest and wealthiest Presbyterian congregation in the Maritimes. In his early preaching, Grant reflected the polemical style of Carlyle in arguing against a Calvinism that had become cold, narrow, and legalistic, and he sometimes slipped into a harsh sarcasm that was resented by conservatives. The sermons also encompassed, however, the Pauline theme of Christian freedom and the influence of Luther as “the man of modern times who had surest faith in spiritual realities.” The sermons were biblical rather than systematically doctrinal, stressed the importance of personal conversion and an active engagement in the world, and were centred theologically in the mystery of the Atonement. He is best categorized as a romantic evangelical; an admirer of the American Dwight Lyman Moody, Grant was quite effective as an evangelist himself, whether preaching to the followers of the late Donald McDonald* on Prince Edward Island in 1871 or during a revival in 1875 in Pictou County.

Grant was also effective in implementing typically evangelical solutions to the social problems of Halifax. He was involved in the direction of the School for the Blind, the Halifax Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, the Children’s Home and Child Immigration Schemes, the Old Ladies’ Home, the Halifax Industrial School, the Halifax Visiting Dispensary, and the Young Men’s Christian Association, and helped raise money for them. In addition, St Matthew’s Church supported a city missionary, James S. Potter, who provided relief to the poor and operated the Night Refuge for the Homeless. But Grant did not consider such works the means to salve the bad consciences of the rich. He preached frankly to his congregation of merchants and shipowners on the relationship of labour and capital and denounced men who made money by risking the lives of their crews in unseaworthy hulks or saw charity at home as a substitute for justice at sea. The causes Grant espoused were supported by Haligonians, in part because he himself lived frugally and gave generously.

His generosity was undoubtedly made easier by his marriage to Jessie Lawson, daughter of one of the leading merchants in the city. Theirs was a happy marriage, despite Jessie’s chronic neuralgia, the presence in their home of her cranky mother, and the loss of George, who was mentally retarded, at the age of 12. Surviving letters suggest that Jessie’s reflective, rather introverted nature helped hold Grant’s self-assurance in check; he played the hero for her as he had for his mother. Grant was less successful as a father to William Lawson, who inherited something of his mother’s sensitive and pensive nature and who found his father overbearing.

Another Halifax institution which received Grant’s attention was Dalhousie College. Following the union in 1860 of the Presbyterian Church of Nova Scotia with the Free Church of Nova Scotia, the new church set out with the Kirk to re-establish Dalhousie as the provincial university. Grant, whose congregation included William Young*, the chairman of the board of governors of Dalhousie since 1848, made good use of his old connections at the West River seminary in helping along the negotiations which resulted in a new university act in 1863. The two churches endowed chairs and James Ross transferred his classes from his seminary, now based at Truro, to Dalhousie and became its president. Grant sat on the board of governors until 1885. In revitalizing Dalhousie, in participating in cooperative mission ventures such as that supporting John Geddie* in the New Hebrides, and in working for the establishment of a common theological hall for Presbyterians, Grant also aimed for a union of all Canadian Presbyterian bodies. Grant was a member of the joint union committee which met in 1870 and, as moderator, represented the Maritime synod of the Church of Scotland at the conference in Montreal in 1875 when the Presbyterian Church in Canada was formed.

The establishment of a national Presbyterian Church was at least in part a consequence of confederation in 1867, for which Grant had been a powerful advocate in Nova Scotia. His views on Canada’s political destiny owed much to those of Joseph Howe*, whom he considered Canada’s greatest political leader. Grant was convinced, however, that Howe was mistaken in his opposition to confederation, and during the heated debates in Nova Scotia had sided with Charles Tupper*, whom he had come to know during the negotiations over Dalhousie College. In 1872 Grant went to Victoria with another member of his congregation, Sandford Fleming*, the chief engineer for the railway to British Columbia promised to that province when it entered confederation the previous year. As secretary of the expedition, Grant travelled some 5,000 miles between 1 July and 11 October. The result was Ocean to ocean (1873), based on diaries he kept. A well-written travel book, the work celebrates the possibilities of the new country, which it nicely observes, and did much to promote interest in the northwest and to generate political support for the railway. In 1883 he would cross the Rockies again with Fleming, who had been asked to report on the work of Albert Bowman Rogers*.

One of the themes which finds at least an oblique expression in Ocean to ocean is the importance of spiritual unity in overcoming Canada’s linguistic, cultural, and racial divisions. Grant’s ideal of a national church that would be the heart of Canadian patriotism was expounded more fully in 1874 in his address to the Dominion Evangelical Alliance, which he had helped organize, and in 1884 he would urge a theological rapprochement with “Arminian” Methodists as a first step. A national church remained a goal throughout his career.

In 1877 the general assembly of the Presbyterian Church met at St Matthew’s Church and the major item of business was the continuing heresy trial of Daniel James Macdonnell*. The underlying issue was how closely the church would be tied to the letter of the Westminster Confession. While recognizing the need for such confessions, Grant favoured a revised statement and led the fight against the “keen, relentless, inquisitorial attitude” of more conservative Presbyterians. As he had correctly predicted to Agnes Maule Machar*, the ambiguous conclusion of the trial amounted to a victory for those in favour of construing the Westminster Confession liberally. As if to underscore the significance of the trial’s outcome, Grant was installed soon afterwards, on I December, principal and primarius professor of divinity of Queen’s College at Kingston, Ont.

Rivalry between the various factions and colleges in the Presbyterian Church, especially during the union negotiations, had put Queen’s future at serious risk. The most urgent need was financial. A fundraising campaign by his predecessor, William Snodgrass, had allowed the college to survive but it was still running at a deficit. Making magnificent use of his “occult powers” as a fund-raiser, Grant undertook a campaign in 1878 to obtain $150,000 to enable Queen’s to buy land, erect new buildings, and establish new chairs of theology and physics. Despite the success of this campaign, the lack of money was a constant concern throughout his principalship, and he was forced to undertake a second major campaign in 1887. Because the Presbyterian Church was not willing to provide the money required to run a modern university, it became increasingly clear that government funding was necessary if Queen’s were to expand, but denominational ties made this politically impossible. Grant’s solution during the 1890s was to siphon money into the university coffers through the nominally independent School of Mining and Agriculture, established in 1893, and to take steps towards severing the legal link between the church and Queen’s except for the theological college.

During the 1880s there was considerable pressure exerted on Queen’s to federate with the University of Toronto. The theoretical advantages of one well-funded non-denominational provincial university were clear and Grant had made that case in relation to Dalhousie. But he felt that Ontario was large enough to have more than one university. Arguing the benefits of pluralism and seeing an opportunity to realize his ideal for Queen’s, Grant fought hard for its existence and independence. He declined in 1883 an offer to become minister of education for Ontario and in 1884 a proposal that would probably have made him president of University College in Toronto. Instead, taking advantage of its freedom from both church and government control, he transformed Queen’s from a small and struggling denominational college of 90 students into what was, by the time of his death, the university for eastern Ontario, with an enrolment of 850. Sir Robert Alexander Falconer*, president of the University of Toronto, said in 1927 of the university Grant left behind him: “It is safe to say that no Canadian university has ever had at one time a group of greater teachers in the humanities.”

As principal, Grant also oversaw the rapid growth of scientific education at Queen’s. A doctorate in science was granted in 1892, the year before the mining school and a faculty of applied science, with Nathan Fellowes Dupuis* as dean, were established. His efforts in this direction were ably supported by his friend Sandford Fleming, who had become chancellor in 1880. While scorning the pretensions of positivism, Grant maintained a sense of balance at a time when tensions between science and theology were running high, and he was guided by a deep conviction that the truths of both could not ultimately contradict each other. Grant was a founding member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1882 and served as its president in 1890–91.

Grant’s tenure as principal witnessed the establishment of a lectureship and later a chair, endowed by James Robert Gowan, in political and economic science, both held by Adam Shortt*. Keenly interested in the social problems attendant on Canada’s industrialization, Grant was sceptical of popular nostrums such as prohibition and Henry George’s single tax. He favoured a more thorough analysis of facts, a larger dependence on expertise in arriving at pragmatic solutions, and a greater reliance on the power of the pulpit than many of his clerical contemporaries. His own liberal orientation had a determining influence on the Queen’s tradition of political economy, which through Shortt, Oscar Douglas Skelton*, and their students would dominate the federal civil service in its formative years. Grant’s liberal views were also reflected in the admission of women to regular classes at Queen’s in 1879, a fact of which he was very proud, and the establishment of the Women’s Medical College in 1883.

Under Grant, Queen’s also pioneered university extension programs in Canada in the early 1890s. Particularly notable were a program in English and political science in Ottawa and alumni theological conferences which became an annual event from 1893. The curriculum for both implied the denial of any sharp distinction between the sacred and the secular: Grant lectured on theological topics in Ottawa while courses on literature and political science were included in the program for clergy. Queen’s thus reflected the assumption of an established church that Christianity lay at the heart of national culture and at the centre of the educational task. Arts, science, and theology were to be studied together, and the educational ideal was a clear grasp of facts from the perspective of faith. Through the extension programs and the Queen’s Quarterly, which Grant started in 1893 and which he served as editor-in-chief, the missionary impulse of the “Queen’s spirit” and its ethic of public service to the nation spread far beyond Queen’s. Alfred Fitzpatrick*, a graduate and the founder of Frontier College, was not alone in his judgement that Grant was “Canada’s greatest force and personality in education and statesmanship.”

As professor of divinity, Grant inherited an 18th-century curriculum consisting mainly of the study of works by William Paley, Joseph Butler, and George Hill. Paley, whose writings Grant dismissed as “sawdust . . . to the soul,” was soon dropped. Butler’s Analogy of religion (1736) and Hill’s exposition of Calvinism in Lectures in divinity (1821) were retained, but supplemented with the “reverent criticism” of moderate scholarship. While not an original scholar himself, Grant read widely and had a good grasp of the main lines of the debates in biblical scholarship. His favourite texts included Heinrich Georg August von Ewald’s History of Israel (1869) and the works of scholars in Scotland like William Robertson Smith and Alexander Balmain Bruce. Philosophical idealism, and the theology of the Incarnation to which it gravitated, made little impact on Grant. He retained the practical common-sense orientation of his own education in Scotland; as John Watson* observed, he was “utterly unspeculative.” Grant’s role in steering the Presbyterian Church through the dangerous theological shoals of the late 19th century was that of a mediator. Deeply convinced of the harmony between faith and reason, he held to the broad-church policy of holding “old orthodoxy” and “new criticism” together, and waited for the emergence of a new theological synthesis, for which he looked to Germany. To Grant, elected moderator in 1889, belongs at least some of the credit for the absence in Canadian Presbyterianism of the theological polarization that troubled Presbyterians in the United States in the 1890s. Grant had delivered an address at the Pan-Presbyterian Alliance in Philadelphia in 1880 and did so again when it met in Toronto in 1892. In 1893 he spoke on behalf of Canadian Protestantism at the Congress of Religions held in conjunction with the Columbian exposition at Chicago.

Grant’s interest in comparative religion, which dated from his student days, was reinforced by years of involvement in committees for church missions and by a trip around the world in 1888. His only book on a theological topic, The religions of the world (1894), presents other religions sympathetically from the perspective of one who none the less believed that only Christianity could ultimately meet the needs of the “universal reason and conscience” of the race. The final chapters on “Israel” and “Jesus” highlight the theme of redemptive suffering in the elected nation and its culmination in the sacrificial destiny of the elected Son.

Using his position as principal of Queen’s as a pulpit, Grant, like his hero Oliver Cromwell and his contemporary William Ewart Gladstone, urged a moralization of national politics. Although he recognized the necessity of political parties, Grant avoided partisan commitments and saw his role as that of a disinterested bystander engaged in the task of shaping an intelligent public opinion. In a steady stream of magazine articles, he championed such causes as university education for women in 1879, aboriginal rights in British Columbia in 1886, and Catholic schools in Manitoba in 1895, and he denounced restrictions on Asian immigration to Canada as early as 1881. He advocated profit-sharing schemes, and urged in 1896 a “new crusade” against Turkey for its treatment of Armenians. His morally driven patriotism is evident throughout Picturesque Canada, published in instalments from 1882 to 1884, which he edited and partly wrote.

It was a concern for Canada’s contribution to the establishment of international law that led him to become a leading Canadian advocate for imperial federation. Grant saw the British empire as a providential opportunity: it represented “not merely a nation or a race . . . but world-wide principles of freedom, justice and mercy to every people, every race, every colour, and every creed.” He met with Joseph Chamberlain in London in 1888 and, after returning from his world tour, served as president of the Imperial Federation League in Kingston and took a prominent role in campaigns against commercial union and for imperial preference. He strenuously opposed the annexationist arguments of Goldwin Smith: amidst much gloom and pessimism about Canada’s prospects to which Smith gave eloquent expression in the 1890s, Grant preached hope and faith in Canada’s destiny within the empire. Never a jingoist, Grant saw the South African War as tragic. He had been attracted to the sturdy piety of the Boers when he visited South Africa and although eventually supportive of Canada’s decision to send troops, he was quick to urge a magnanimous peace.

Grant’s imperialism also included a generous appreciation of French Canadians. His French was quite good and he respected the strengths and achievements of Catholicism when such recognition was rare among Protestants. Grant was on friendly terms with Louis Fréchette and Henri-Raymond Casgrain, and in a time of ethnic and religious polarization he saw himself as Quebec’s ally against narrow chauvinism in English Canada. In 1889 he refused to join Daniel James Macdonnell in a crusade against Quebec’s Jesuits’ Estates Act or D’Alton McCarthy* in his “equal rights” campaign. Premier George William Ross* of Ontario called Grant a peacemaker and recollected the “many occasions he gave eloquent utterance to the part played by the Canadians of French origin in shaping the constitution of the country.”

Grant’s most lasting achievement is Queen’s, where, as noted by Hilda Marion Neatby*, he “set his personal mark . . . so indelibly that its history in his time has almost to be written in personal terms.” By the end of his life, “Geordie Our King” had assumed legendary proportions. A student poem of the period asked rather belligerently:

Have you not heard of G. M. Grant,

Who always can, and never can’t,

Whose fist is soft as adamant?

Why that’s our Geordie!

A smack of Cromwell, cautious, bold,

Our soldier Geordie;

Of Luther also in his mould,

Our prophet Geordie!

The Cambridge classicist Terrot Reaveley Glover, who began his career at Queen’s, wrote of Grant that “it was yet no small part of the education that Queen’s gave to associate with a man of such outlooks, such range and such political integrity. . . . Teacher, builder, driver – call Grant what you will; he saved the University from intellectual ruin as surely as he did from financial; and, with all his limitations, his presence, his word, his glance, were inspiration.” Grant’s limitations included a fiery temper over which he never gained complete control. As a clergyman, he might have made better use of the soft answer to turn away wrath; however, sarcasm came more instinctively. His ambitions for Queen’s sometimes led him to make heavy demands on his staff and tempted him towards manipulating them; they occasionally grumbled about working for “Napoleon.” He had great natural political instincts and one of his biographers stated that except “for the grace of God . . . he could have gone very far in the use of other men for his purposes.”

Within the Presbyterian Church, Grant was an influential champion of liberal theological and political views. He supported historical criticism of the Bible and did much to wean Presbyterians from a literal adherence to the Westminster Confession. But he was emphatically not a modernist in the 20th-century sense. He was appreciative of the strengths of the Calvinism that had characterized his Pictou County childhood, and he denounced as superficial those who wished to jettison theological tradition without understanding it. Neither scholastic Calvinist nor liberal modernist, Grant tried to steer the Presbyterian Church to the middle ground at which it would arrive a century later. His ecclesiastical influence was not limited to Presbyterians. Salem Goldworth Bland* considered him to have exercised a broadening role on Canadian Methodism during a crucial period of transition. Certainly he had a considerable influence on Bland: the origins of both the Social Gospel and the United Church of Canada have been traced to Grant – though he himself was not a socialist and it is not obvious, given the theological sea change that took place after his death, that he would have voted in favour of church union in 1925.

Grant’s patriotism flowed from his Christian faith. His robust hope for Canada’s future was tied to his conviction about the divine task to which the British empire had been called. For him there was no contradiction between “Canada First” and imperialism “of the best sort.” Shortly before his death he was made a cmg. Obituary tributes did not hesitate to rank his contribution to Canada with those of Sir John A. Macdonald* and Joseph Howe.

George Monro Grant published numerous books and articles, including the following: Sermon preached at the National Scotch Church, Saint Matthew’s, Halifax, on the morning of the first Sunday of 1866 (Halifax, 1866); Sermon preached before the Synod of Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, in connection with the Church of Scotland, on June 26th, 1866 (Halifax, 1866); Reformers of the nineteenth century: a lecture delivered before the Young Men’s Christian Association, of Halifax, N.S., on Tuesday evening, Jan. 29, 1867 (Halifax, 1867); Ocean to ocean: Sandford Fleming’s expedition through Canada in 1872 . . . (Toronto and London, 1873; repr. Toronto, 1970), which was also issued in several revised eds., all published at Toronto: 1877 (repr. Rutland, Vt, and Tokyo, 1967), 1879, and 1925; Picturesque Canada: the country as it was and is, for which he was both editor and a contributing author, which appeared at Toronto in 36 instalments from 1882 to 1884, and which was also issued in two volumes (1882-[84]); Our five foreign missions ([Kingston, Ont.?, 1886?]); “Progress and poverty,” Presbyterian Rev. (New York and Edinburgh), 9 (1888): 177–98; Advantages of imperial federation: a lecture delivered at a public meeting held in Toronto on January 30th, 1891, under the auspices of the Toronto branch of the Imperial Federation League (Toronto, 1891); several articles in Sunday Afternoon Addresses (Kingston), a publication of the students of Queen’s Univ., 1891–94; Canada and the Canadian question: a review (Toronto, [1892?]); The religions of the world in relation to Christianity (Toronto, [1894]), a revised edition of which appeared as The religions of the world (London and Edinburgh, 1895); “Thanksgiving and retrospect,” Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston), 9 (1901–2): 219–33; “The outlook of the twentieth century in theology,” American Journal of Theology (Chicago), 6 (1902): 1–16; and Joseph Howe (Halifax, 1904) (a second edition,. . . to which is added Howe’s essay on the organization of the empire, appeared in 1906). A complete listing of his writings appears in D. B. Mack’s full-length study, “George Monro Grant: evangelical prophet”

Grant’s papers are preserved at NA, MG 29, D38.

Carl Berger, The sense of power; studies in the ideas of Canadian imperialism, 1867–1914 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1971). Cook, Regenerators. T. R. Glover and D. D. Calvin, A corner of empire: the old Ontario strand (Toronto and Cambridge, Eng., 1937). W. L. Grant and [C.] F. Hamilton, Principal Grant (Toronto, 1904), repr. as George Monro Grant (Edinburgh and Toronto, 1905). C. F. Hamilton, “‘The makers of Queen’s’: Principal Grant,” Queen’s Rev. (Kingston), 1 (1927): 33–38. H. [M.] Neatby and F. W. Gibson, Queen’s University, ed. F. W. Gibson and Roger Graham (2v., Kingston and Montreal, 1978–83), 1. G. [G.] Patterson, The history of Dalhousie College and University (Halifax, 1887).

Cite This Article

D. B. Mack, “GRANT, GEORGE MONRO,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grant_george_monro_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grant_george_monro_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | D. B. Mack |

| Title of Article: | GRANT, GEORGE MONRO |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 26, 2025 |