LOFT, FREDERICK OGILVIE (known in Mohawk as Onondeyoh, meaning “beautiful mountain”), lumberman, journalist, civil servant, author, activist, army officer, and Mohawk pine tree chief; b. 3 Feb. 1861 on the Six Nations Reserve, Upper Canada, son of George Rokwaho Loft and Ellen Smith; m. late June 1898 Affa Northcote Geare (d. 21 May 1945) in Toronto, and they had three daughters; d. there 5 July 1934.

Fred Loft’s parents belonged to the Christian community, the largest religious group among the Six Nations of the Grand River. The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) there contained two distinct religious worlds: the Mohawk, Oneida, Tuscarora, and Iroquois allies such as the Delaware accepted Protestant Christianity; the Seneca and Onondaga adhered to the code of Skanyátaí.yoˀ (Handsome Lake), the Seneca prophet associated with traditional Iroquoian religious practices in the early 19th century. The other Iroquois nation, the Cayuga, included both Christian and Handsome Lake (or Longhouse) adherents. Generally, the Christians promoted adjustment to the larger society, through the adoption of commercial agriculture and education in English, while the Longhouse people championed the old customs of the Six Nations.

Loft’s mother, Ellen Smith (Konwajonhondyon, meaning “left alone by the fire”), gave her children English and Iroquoian names. She was the granddaughter of Oneida Joseph, a well-known warrior under Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*] in the American Revolutionary War. Her father, Peter Smith, a prosperous Mohawk farmer, served in the 1850s as the Six Nations’ interpreter. When Ellen was quite young, her mother died and her father married a granddaughter of Brant. In terms of social prominence, the Smiths stood at the top level of Christian Iroquois society. Their guests included American ethnographer Lewis Henry Morgan, who called in 1850 along with Ely Samuel Parker, his Iroquois assistant and a future general in the American army. Ellen, who remembered the visit for the rest of her life, had married in 1849 George Loft, a Mohawk from the Tyendinaga Reserve on the Bay of Quinte near Belleville. As a wedding present her father gave the couple a small farm, Forest Home, in the northeast corner of the Six Nations territory.

Since his parents spoke English fluently, Fred, their middle son, grew up with this language as well as his native Mohawk. He and his brothers William D. (Dewaselakeh, meaning “double axe”) and Harry (Kalonyoudyeh, “flying sky”), the only three of the six children to outlive their father, were raised in the Anglican tradition. The Christian faith remained important to George and Ellen Loft, who donated land from their farm for Christ Church in 1873. In a note registered just after George’s death in 1895, the parish record refers to his “upwards of 40 years engaged in mission work in this locality as Catechist, Interpreter and Lay Reader.”

The Lofts also valued education. Fred attended a First Nations primary school near Forest Home until the age of 12. He then boarded for a year at a residential school (the Mohawk Institute) in Brantford. He detested it. Years later he bitterly remembered that he “was hungry all the time, did not get enough to eat.” There were other deprivations: “In winter the rooms and beds were so cold that it took half the night before I got warm enough to fall asleep.” His father and mother, who always allowed him a great deal of freedom, supported his decision not to return, but Fred still desperately wanted a full education. At 13 he walked eight miles a day, round trip, to the public school in neighbouring Caledonia, a non-native town. The next year he moved there to be closer to school, and he worked for his board and lodging. After completing elementary school, the determined young man immediately entered Caledonia’s high school, where he studied from 1878 to 1881.

The encouragement of his parents and his success in school gave Loft great confidence. Although discrimination was rife in the communities around the Six Nations territory, any negative encounters in Caledonia did not deter him. After high school, according to one biographical source, he felt “equipped enough to face the world of competition – no matter what.” A variety of challenges followed. For several years he worked in the forests of northern Michigan, rising from lumberjack to timber inspector. Ill health forced him to leave the bush and go back to the Grand River in 1884–85. Upon his recovery he returned to school. He received a full scholarship to study bookkeeping at the Ontario Business College in Belleville. On graduating, he could not find employment as a bookkeeper, a setback that led him momentarily into journalism. He worked as a reporter for the Brantford Expositor for six months, and covered locally the general election of February 1887. (All eastern Canadian male status Indians who met the property qualification had just received the federal franchise, a right that would be withdrawn in 1898.) Loft was a staunch Liberal, so much so that fellow Mohawk John W. M. Elliott, a Conservative organizer, had advised Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* on 10 January that Loft’s letters to the Department of Indian Affairs should go unanswered. The reporter, he explained, “is a stiff & bigotted Grit, & desires to make a handle of everything which he elicits in the shape of information from ‘Headquarters’ against our party & Government.”

Following his time with the Expositor, Loft worked for two years as a lumber inspector in Buffalo, N.Y. Then, around 1890, his partisan credentials helped him obtain a new job in Toronto. The provincial Liberal government of Oliver Mowat* appointed him an accountant in the bursar’s office of the Asylum for the Insane. He would remain in this position for the next 36 years.

Toronto took little interest in contemporary First Nations matters in the late 19th century. Natives were a more distant people to its citizens than to Canadians in other urban centres. Unlike Montreal, Vancouver, and Calgary, it had no neighbouring reserve; in 1901 only 36 status Indians would be enumerated in Toronto. In 1891 Goldwin Smith*, a former professor of history at the University of Oxford and one of the city’s leading intellectuals, dismissed the native North American in two sentences: “The race, everyone says, is doomed.... Little will be lost by humanity.”

After Fred Loft’s arrival in Toronto, he continued to take an interest in native issues. He tried to organize a new political grouping of the First Nations of Ontario. On 9 Oct. 1896 he wrote to Hayter Reed, the federal deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs, that “the Six Nations & the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte the most foremost of the Indians in Canada” no longer attended the grand general councils held by Ontario First Nations. Subsequently, he suggested the formation of an organization that would once again include both the Iroquois and the Ojibwa. Drawing on his newspaper background, he reformulated his arguments in a letter in the Toronto Globe on 7 November. He wanted greater autonomy for the First Nations. The Department of Indian Affairs, he argued, “should more readily adhere to our decisions and wishes, as expressed through the wisdom of our respective councils, rather than submit, as has too often unfortunately been the case, to dictation.” Nothing came of the suggestion.

Through the late 1890s and the first years of the new century, the outgoing Loft became energetically involved in his adopted community, which had much more to offer than the smaller centres of Caledonia, Brantford, or Belleville. In 1898 the 37-year-old government employee married Affa Geare of Chicago, a former Torontonian of British ancestry who was 11 years his junior. They had met at a friend’s place in Toronto. Affa gave birth in 1899 to twins, Henrietta Gertrude and Ellen Emma Leska; Leska died in 1902 but another daughter, Affa Northcote, was born in 1904. The church-going Lofts led a busy, upper-middle-class life; their social circle was extensive. They had season tickets to two theatres and frequented Abraham Michael Orpen’s racetrack – Fred was an avid horseman. He took part in masonic affairs through St George’s Lodge, was keen on billiards, and sang, played the piano, and, with Affa, hosted musical parties. Joined on occasion by her husband as a speaker, Affa was active in the American Women’s Club of Toronto, the United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada, and the Women’s Art Association of Canada. Their daughters went to the respected Toronto Model School.

Ministers, doctors, lawyers, and heads of organizations counted Fred Loft as a friend. He was acquainted with Sir Adam Beck*, the head of Ontario Hydro, whose photo hung in the Lofts’ home. Through mutual First Nations interests, he knew David Boyle*, the curator of the Ontario Provincial Museum; in a 1907 article Boyle considered him “a highly intelligent gentleman, of good appearance, good address, and good common sense.” (Tall and physically impressive, Fred dressed conservatively in navy blue or dark grey suits.) For some time the Lofts lived on the same street as George Taylor Denison*, Toronto’s senior police magistrate, who described Fred in 1906 as “a respectable gentleman of fairly good education, and much better qualified for the franchise than 95 per cent of those who have it.” First Nations friends such as the famous Iroquois runner Tom Longboat* visited Loft.

In the years before World War I, Loft continued to draw attention to native affairs. He wrote on the future of the “Indian” for the Globe in 1908 and a year later Saturday Night (Toronto) published his series on “the Indian and education,” a topic of particular concern to Loft. In the first of his four articles, he advocated an end to residential schools as “veritable death-traps,” so unsanitary were they; he called instead for day schools on reserves. In Ontario’s Annual archæological report, he wrote on a lighter topic, snow-snaking, the favourite winter sport of the Six Nations.

The Six Nations were strongly rooted in their past [see John Arthur Gibson*], and Loft contributed to this consciousness. His articles on Joseph Brant and the “Iroquoian loyalists,” in the Annual transactions of the United Empire Loyalists’ Association, extolled Chief Brant and others in the pro-British community among the Six Nations. His loyalist essay refers to “the early attachments and fidelity of the Iroquois to the British Crown.” Six Nations warriors also fought alongside British troops in the War of 1812 [see Tekarihogen*]. At the celebration in 1912 of the 100th anniversary of Sir Isaac Brock*’s wartime victory at Queenston Heights, “Warrior F. Onondeyoh Loft” spoke on the same platform as Mohawk chief A. G. Smith (Dekanenraneh).

Whenever possible Loft returned to the Six Nations to visit his mother, a widow since his father’s death in 1895. On Sundays at Forest Home, the ardent Anglican attended church. His niece, Bernice Loft Winslow (Dawendine), recalled that he practised his Mohawk after services but she noticed that, because he had been away for so many years, he had lost some of his fluency and occasionally put words in the wrong places. His daughter Henrietta, who spent many summers at Forest Home with her sister Affa, remembered “its wonderful trees, and woods. And an acre of violets by the house.... Organ & violin there, too – for music. Many visitors, and much, much laughter – My grandmother was well educated – But a woman of few words – plump & gentle, but she ‘ruled the roost.’”

Yet, despite this attachment to the Six Nations and his wide social acceptance, Fred Loft felt ashamed of his low-ranking civil service post and his legal status as a ward of the crown under the federal Indian Act. On 28 Jan. 1907 he wrote to Liberal prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* that, with regard to his asylum job, “the position I hold, which is only a clerkship has never been to my way of thinking, a fitting recognition of what my labors meant. Worse than all my salary has been very small.” For whatever extras the family wanted, they depended on Affa’s business activity. She bought and sold houses, rented to roomers, and owned stock. Their frequent changes of address in Toronto give the impression that the Lofts were drifters, but in fact they moved as a result of Affa’s engagement in the local real-estate market.

In 1906 Loft had applied to enfranchise, that is, to give up his native status under the Indian Act, cease to be legally recognized as a ward, and become an ordinary citizen. Though he cherished his First Nations heritage, he also wanted to participate fully in the dominant society. After all, he had married a non-indigenous woman and had joined the larger workforce. Once he learned that the Six Nations Council refused to endorse his application, however, he withdrew it. The council’s reluctance to lose Onondeyoh had led him to reconsider, and he came forward with another plan.

Loft decided to apply for the post of superintendent of the Six Nations, the top federal job in the Grand River community. In his 1907 letter to Laurier, he explained: “There is perhaps nothing I have desired in my life more than becoming if possible the Superintendent of the Six Nations of Brant; should it be considered by your Government that one of themselves would be capable of performing the duties of the office.” One week later the council approved his application. Despite Loft’s impeccable Liberal credentials and the council’s endorsement, however, the government declined to make the appointment. Council still wanted him as superintendent, and in early January 1917 it again recommended his appointment, but without success.

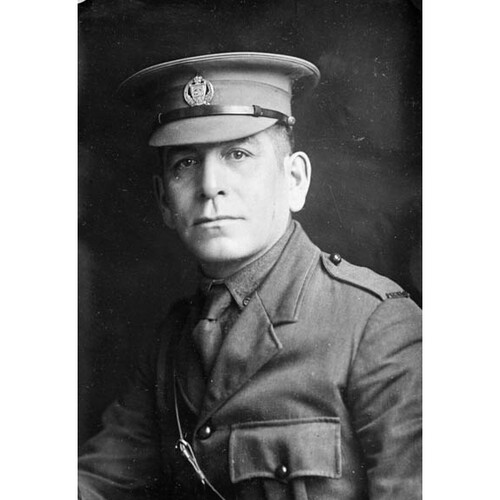

After the outbreak of World War I, Loft, a loyal supporter of Britain, had visited reserves throughout Ontario to promote recruitment. In 1917, with three years of active militia service in Toronto, he was commissioned a lieutenant in a “forestry draft” on account of his early experience in the lumber industry. To qualify for overseas duty he had reduced his age at enlistment from 56 to 45. The examining doctor accepted him at his word; he stood just over 5 feet 11 inches, weighed 170 pounds, and was in good shape. All his adult life he had taken excellent physical care of himself. He never owned a car, always walked, and, according to his daughter Henrietta, exercised every morning.

Although Loft went to Britain with the 256th Infantry Battalion, which then helped man the 10th Railway Battalion, he was later transferred to the Canadian Forestry Corps. In France, he liked the area and the people where the corps was stationed. “I have fallen in love with the country, its people and the language which I’m making every possible effort to familiarize by nightly study,” he wrote on 6 Dec. 1917 in a letter to a civil-service friend in Canada. On 7 August, during his half-year absence overseas, the Six Nations Council had conferred on him a pine tree chieftainship, an honour given only to the most outstanding members of the Grand River Iroquois Confederacy. As the council’s representative, he met with King George V at Buckingham Palace on 21 Feb. 1918, just before leaving for Canada.

On his return the Mohawk veteran dreamed of how he could help the First Nations: he would work to persuade the government to improve the standard of education it offered them. More day and high schools should be established on reserves. This goal became one of the main objectives of the League of Indians of Canada, which Loft founded in December 1918 at the Council House in Ohsweken, on the Six Nations Reserve. The centuries-old Iroquois League inspired Loft to found this national organization, the first in Canada that aimed to see “all Indians being united in one great association,” though he may have been aware of the collective potential in such regional alliances as the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia [see James Alexander Teit*]. First Nations throughout the country had already been greatly irritated by the federal government, which in 1911 amended the Indian Act to permit the expropriation of reserves adjacent to or within large towns. The delegates to the Ohsweken meeting in 1918 denounced the change. As Loft stressed in his circular letter of 26 Nov. 1919 to native groups across Canada, the First Nations needed to “free themselves from the domination of officialdom.” The new league held annual meetings at Sault Ste Marie, Ont. (1919), Elphinstone, Man. (1920), Thunderchild Reserve, Sask. (1921), and Hobbema, Alta (1922). As its first president and secretary-treasurer, Loft attempted to deal with every complaint that reached him. The Toronto Daily Mail and Empire later recalled in his obituary that, before and after organizing the league, “he travelled for years almost continuously fixing up a trapper’s dispute, appealing to officials at Ottawa for justice to his clients, after the war helping the Indian veterans who were entitled to pensions.” To encourage membership and attendance at the annual meetings, he sent circulars to band chiefs and individuals alike. He did so largely at his own expense, since, despite his appeals, he received little financial support.

Duncan Campbell Scott*, the deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs, regarded Loft as a subversive and the league as a roadblock to efficient administration. To destroy its effectiveness, he focused on Loft. Under another amendment to the Indian Act, passed in July 1920, Scott tried to have his Indian status removed, to enfranchise him in effect. In a statement to a special committee of the House of Commons in April, Loft had presented the league’s position on compulsory enfranchisement. The league did not oppose it “so long as it is based upon educative ideals and a proper training for the eventual assumption of the individual for the higher status of citizenship involving all its responsibilities.” But how, the president added, could the government consider such a policy when “scarcely five per cent of the adult population of the reserves are capable of corresponding intelligently.”

Loft’s stance on enfranchisement reveals him as a moderate, anxious for his people to enter into the larger society around them. In contrast, Levi General [Deskaheh*], a Cayuga chief in the Six Nations Council and a member of the Longhouse community, did not want the Iroquois to join the dominant society. Instead, he worked to secure international acceptance of the Six Nations as a sovereign entity. His agitation greatly upset Loft. In a letter of 18 Dec. 1922 on the sovereignty question to William Lyon Mackenzie King*, the new Liberal prime minister, he emphasized that he saw the Six Nations as subjects of His Majesty, “in no degree differing from the acknowledged and accepted status of other Indians of Canada.” The Cayuga chief, Loft stated pointedly, “holds no mandate from the people of the Six Nations to warrant his actions.”

As a result of King’s abolition of compulsory enfranchisement earlier in 1922, Scott’s attempt to have Loft’s Indian status removed failed, but he still saw the moderate Mohawk as a radical, every bit as dangerous as Deskaheh. The department’s continual opposition to the League of Indians hampered its growth. Loft’s minimal resources, particularly after he retired from the civil service in 1926, held back expansion. His subsequent move to Chicago with his wife for four years (1926–30) because of her poor health made it difficult for him to coordinate league activities. After his return to Toronto, he did his best to resume his work. For example, on 17 Nov. 1932 the Toronto Daily Star reported his belief that the jailing of some “Indians” for poaching under provincial game laws was contrary to their rights under the British North America Act. Such outspokenness did nothing to divert Scott’s critical attention. In the early 1930s he briefly considered criminal charges against Loft for attempting to raise money for land-claim issues. At the same time, Loft’s health was deteriorating. He died in Toronto in July 1934.

By this time the League of Indians, apart from its branches in Alberta and Saskatchewan, had effectively become defunct. Other leaders nonetheless took up Fred Loft’s cause of a nationwide organization, most recently the National Indian Brotherhood, formed in 1968, and its successor, the Assembly of First Nations, chartered in 1985. The First Nations of Canada owe a great deal to Onondeyoh/Fred Loft, an early 20th-century political visionary.

This biography is largely based on the author’s unpublished article “Onondeyoh: the Grand River and Toronto background of Fred Loft (1861–1934), an important early twentieth century First Nations political leader” (presented at the Conference on Twentieth Century Canadian Nationalisms sponsored by the Organization for the History of Canada, Univ. of Toronto, 16–18 March 2001). A copy is available in Loft’s file at the DCB. Loft’s articles include: “The future of the Indian,” Globe, 8 Feb. 1908: 8; “The Indian and education,” Saturday Night (Toronto), 12, 19 June and 3, 17 July 1909; and “Indian reminiscences of 1812,” Saturday Night, 11 Sept. 1909. His addresses to the United Empire Loyalists’ Assoc. of Canada were published as: “Captain Joseph Brant, – Thayendanega (head chief and warrior of the Six Nations),” United Empire Loyalists’ Assoc. of Canada, Annual trans., 1904 to 1913 (Brampton, Ont., 1914), 57-61; and “Iroquoian loyalists,” Annual trans., 1914 to 1916 (Toronto, 1917), 68-79.

LAC, R10383-0-6; R10811-0-X, 118777, 118779; RG 10, 2285, file 57169-1B, pt.3. Daily Mail and Empire (Toronto), 7 July 1934. Toronto Daily Star, 8 Feb. 1907 (interview with Loft), 11 Feb. 1907, 6 July 1934. Peter Kulchyski, “‘A considerable unrest’: F. O. Loft and the League of Indians,” Native Studies Rev. (Saskatoon), 4 (1988): 95–117. R. R. H. Lueger, “History of Indian associations in Canada (1870-1970)” (ma thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1977). J. L. Taylor, Canadian Indian policy during the inter-war years, 1918-1939 (Ottawa, 1984). E. B. Titley, A narrow vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, 1986).

Revisions based on:

LAC, RG 10, vol.3211, mfm. C-11340, file 527787, pt.1 (Formation of a Canadian League of Indians by F. O. Loft of the Six Nations Band), Loft to chiefs and brethren, 26 Nov. 1919.

Cite This Article

Donald B. Smith, “LOFT, FREDERICK OGILVIE (Onondeyoh),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 3, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/loft_frederick_ogilvie_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/loft_frederick_ogilvie_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald B. Smith |

| Title of Article: | LOFT, FREDERICK OGILVIE (Onondeyoh) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2009 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | February 3, 2026 |